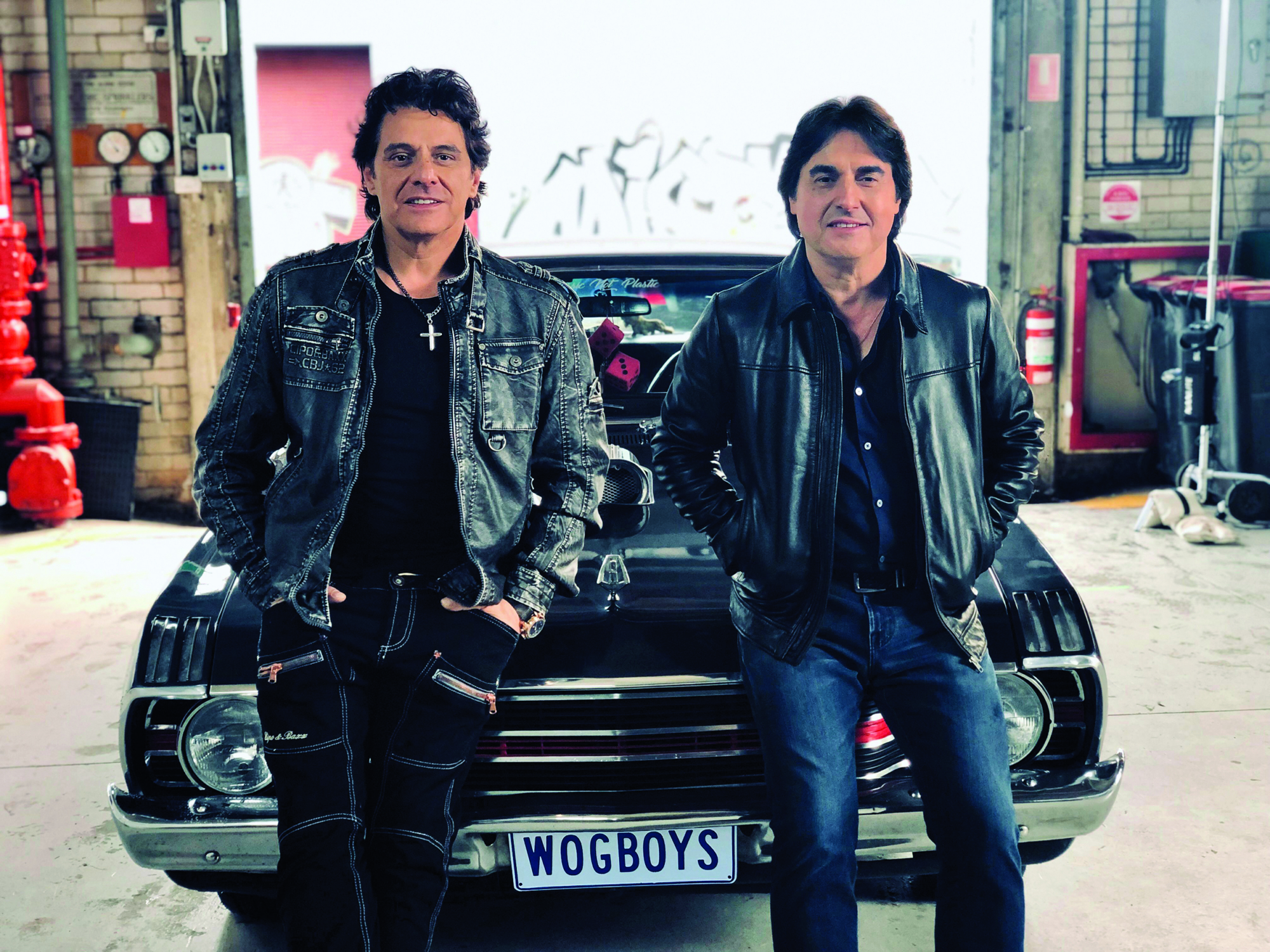

For Nick Giannopoulos, Wog Boys Forever (Frank Lotito, 2022) is a continuation of a decades-long career as a writer and actor exploring identity through comedy. The Greek-Australian performer first rose to fame in the 1980s through the comedic stage play Wogs out of Work[1]See Murray Bramwell, ‘Community Announcement’, The Adelaide Review, no. 60, February 1989, p. 27, available at <https://murraybramwell.com/?p=1404>, accessed 13 December 2022. before co-creating, writing and acting in the popular television series Acropolis Now from 1989 and 1992. Making the natural progression from TV to film, Giannopoulos has since created, co-scripted[2]Giannopoulos collaborated with Chris Anastassiades on the scripts of these two features; Wog Boys Forever marks his first solo feature screenplay. and starred in the culturally enduring and commercially successful features The Wog Boy (Aleksi Vellis, 2000) and Wog Boy 2: The Kings of Mykonos (Peter Andrikidis, 2010).[3]The first two Wog Boy films made over A$11.4 million and A$4.9 million (not adjusted for inflation) at the Australian box office respectively. See Film Victoria, ‘Australian Films at the Australian Box Office’, 2011, pp. 15, 23, archived at <https://web.archive.org/web/20140209075310/http://www.film.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/967/AA4_Aust_Box_office_report.pdf>, accessed 13 December 2022. At the time of writing, five weeks into its theatrical run, Wog Boys Forever has earned a respectable A$2.9 million. See Jackie Keast, ‘BO Report: Black Panther: Wakanda Forever Dominates’, IF.com.au, 14 November 2022, <https://if.com.au/bo-report-black-panther-wakanda-forever-dominates/>, accessed 13 December 2022. Bringing Giannopoulos and Vince Colosimo back as central characters Steve Karamitsis and Frank Di Benedetto, Wog Boys Forever completes the trilogy.

Through his various comedic explorations of Greek-Australian identity, Giannopoulos has helped usher in a generation of multicultural entertainers in Australia, influencing comedians like Paul Fenech – the Maltese-Australian creator of various SBS series including Pizza and Housos – and Sooshi Mango, a comedy troupe made up of Italo-Australians Andrew Manfre and siblings Joe and Carlo Salanitri. Like Giannopoulos, Fenech and the Sooshi Mango trio have used their cultural backgrounds and experiences of growing up in Australia to inform their comedy stylings, in the process often taking possession of the racial slurs that they encountered over the years. This is the logic behind why the word ‘wog’ has been so foregrounded in Giannopoulos’ own work, as the writer and performer has explained in interview:

I’m taking the piss out of the racists – I’m taking [the] piss out of racism. When I make jokes about my community, they’re from the inside out; they’re not from the outside looking in, yeah? I’m not Con the Fruiterer.[4]Nick Giannopoulos, in ‘Wog Boy Nick Giannopoulos Is Back in Town | Straight Talk Podcast | Mark Bouris’, YouTube, 29 September 2022, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ws9UhaOJHyM>, accessed 13 December 2022. A stereotypical representation of a Greek-Australian grocer created and embodied by Anglo-Australian performer Mark Mitchell, Con the Fruiterer was a popular recurring character on the sketch-comedy TV series The Comedy Company in the late 1980s and early 1990s; see Andrew Hornery, ‘Can Race Ever Be Fodder for Comedy? It All Depends on Who You Ask’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 31 May 2020, <https://www.smh.com.au/culture/celebrity/can-race-ever-be-fodder-for-comedy-it-all-depends-on-who-you-ask-20200527-p54wtd.html>, accessed 13 December 2022.

This ‘inside out’ approach to comedy is reinforced by a strong sense of identity, family and community that runs through Giannopoulos’ work. Diversity on screen and representation for multicultural communities is often presented as a way of breaking down barriers and dismantling the constructs of prejudice that exist within society. For Giannopoulos, that fight to establish Greek migrant identity in broader Australian culture is paramount to the success of his work:

The central theme to everything I’ve done is about identity. Because when I was growing up in Australia, I couldn’t work out what my identity was […] They’d call me a ‘wog’ here; I’d go to Greece [and] they’d call me a ‘kangaroola’. Here: ‘Piss off, wog’; Greece: ‘Piss off, kangaroola.’ Where do you want me to go? I didn’t know where I belonged. I didn’t understand. And I also didn’t understand why I was being so marginalised (I mean, I didn’t know that word back then – I know it now); why we were always pushed to the sides; why we were never taken seriously; why we were never given respect. And I realised, in this country, you’ve got to earn your respect. It’s a hard, tough country.[5]Giannopoulos, quoted in ‘Wog Boy Nick Giannopoulos Is Back in Town’, ibid.

When The Wog Boy launched in 2000, the societal impact of the film was immediately felt, with its opening-weekend domestic box office reportedly grossing more than that of Crocodile Dundee (Peter Faiman, 1986).[6]See Thomas Mitchell, ‘“Where’s the Respect?”: Nick Giannopoulos on His Battle to Make Wog Boy 3’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 30 September 2022, <https://www.smh.com.au/culture/movies/where-s-the-respect-nick-giannopoulos-on-his-battle-to-make-wog-boy-3-20220929-p5bm11.html>, accessed 13 December 2022. While a lot of the groundwork for The Wog Boy’s popularity had been established prior to the film’s release through Acropolis Now, it was immediately clear that Giannopoulos had earned the respect of Australian cinema-goers.

I recall first seeing The Wog Boy during its opening weekend with friends, one of whom had migrated from Yugoslavia and was surprised to see a character like Tony the Yugoslav (Costas Kilias) on screen being the recipient of some of the audience’s biggest laughs. It wasn’t just Greek- and Italo-Australian culture being depicted on screen; Tony’s use of the word ‘farken’ as a punctuation mark became part of my friend’s identity, making him feel seen in a way that wasn’t associated with war, trauma or tragedy (as was the case with most Balkan characters presented in locally distributed film and TV works of that era).

Giannopoulos’ understanding of what it means to be seen on the big screen carries across in more than just a narrative sense, with his lead character, Steve, embodying Greek-Australian culture. Whereas Crocodile Dundee’s Mick (Paul Hogan) has his hat and knife, Steve has his Pacer, a leather jacker and Patrick Hernandez’s ‘Born to Be Alive’, accoutrements that have become legendary cultural signifiers in their own right. In The Wog Boy, with a conspicuously 1990s voiceover, Steve talks about who he is: ‘The car; the clothes; the attitude: I dedicated my life to becoming the best wog I could be.’

The hopefully titled third film in the series sees the frequently down-on-his-luck Steve facing his biggest challenge yet. After becoming an accidental celebrity in The Wog Boy and inheriting a beach in Greece in The Kings of Mykonos, Steve begins Wog Boys Forever living as a bachelor in a granny flat and working as a taxi driver, struggling to find a path out of the mid-life crisis he is stuck in and seek out some kind of legacy. While on the job, Steve pulls up to a pedestrian crossing beside his one-time prized possession: a Valiant Pacer. Now in the hands of a young Greek-Australian man, the car’s numberplate has been changed from ‘wog boy’ – the branding Steve once affixed with pride – to ‘malaka’ (Greek for ‘wanker’). As the two cars wait for an elderly woman to cross, Steve goads the Pacer’s driver into a drag race in a bid to show a member of the younger generation what a community elder is capable of. With the Pacer fading into the distance, Steve’s weathered yellow taxi rattles and sputters, barely getting across the crossing before it stalls.

For many Greek-Australians, there was once no marker of identity and status greater than the Valiant Pacer. In the 1970s, the car was so popular within the community that its younger members christened it the ‘wog chariot’,[7]See Dora Houpis, ‘Forget Holden and Ford, the Early Greeks Drove Valiants’, Neos Kosmos, 27 February 2020, <https://neoskosmos.com/en/2020/02/27/dialogue/opinion/forget-holden-and-ford-the-early-greeks-drove-valiants/>, accessed 13 December 2022. partially thanks to its low-cost entry point. Whereas Holden or Ford sedans could cost five to ten times as much secondhand, a Pacer could often be purchased for less than A$1000. In an article about the car’s legacy for Neos Kosmos, Greek-Australian journalist Dora Houpis quotes her brother reminiscing about its appeal: ‘You got a lot of car […] It had muscle, power, grunt. Hoons, like me, couldn’t afford Holden.’[8]Quoted in Houpis, ibid.

The Pacer is a constant throughout the Wog Boy series, with Giannopoulos frequently using it as a point of connection to the Greek-Australian community. In The Wog Boy, Steve is pulled over by police who assume, based on the quality of his car, that he’s on the dole. Explaining why he loves his car so much, Steve proceeds to retrieve an album of shots of the car throughout the years, showing how it was passed to him by his father.

With no kids of his own, the Steve of The Wog Boy treats this visual journal as his family photo album. In Wog Boys Forever, however, his Pacer is gone, and he now yearns for a family of his own. Whereas this new film opens with a chance encounter with the car, it ends with Steve getting married and driving away in the reclaimed Pacer, now bearing the numberplate ‘wog boys’.

While there are welcome elements of nostalgia in this new instalment, other callbacks to the earlier films seem distinctly out of step with the modern world. Wog Boys Forever operates in an anachronistic Australia in which a Derryn Hinch–hosted tabloid current-affairs show is appointment viewing, a nightclub can be disrupted by a well-coordinated dance routine and the sexual proclivities of public figures can shock a nation. And while there is an element of charm in seeing Giannopoulos and Colosimo bounce off each other, they’re saddled with outdated skit-level comedy. One scene sees Frank voicing his frustration at his daughter (Zara Tsolakis) sharing the name of his home’s smart device, ‘Alexis’, and the two responding in unison when he asks it to turn on a light; in another, Steve tries and fails to get into the (aptly titled) Privilege nightclub, resorting to faux kung fu moves in the street to intimidate a bouncer. Then there’s the sequence in which three elderly Italian-Australians – embodied by the Sooshi Mango trio in obvious get-ups – try to entice Steve’s love interest Cleo (Sarah Roberts) to stay with him by gifting her a giant zucchini and a panettone. Such passages are awkward and banal, dragging down the effective political comedy that otherwise runs through the film (as well as the series as a whole).

Wog Boys Forever operates in an anachronistic Australia in which a Derryn Hinch–hosted tabloid current-affairs show is appointment viewing, a nightclub can be disrupted by a well-coordinated dance routine and the sexual proclivities of public figures can shock a nation.

As much as the Valiant Pacer, leather jacket and dancing have resonated with audiences, the condemnation of racism and its place in Australian politics also strikes a chord. In Wog Boys Forever, the villains are powerful Anglo-Australians – notably, immigration minister Brianna Beagle-Thorpe (Annabel Marshall-Roth) and her brother Clayton (Liam Seymour), Pauline Hanson surrogates who yearn for a monocultural Australia and are seeking retribution from Steve for ruining the career of their late mother twenty years previously.

Aware of the comfortable place that racism has in Australian culture, Giannopoulos makes it clear in his script that Brianna is at no risk of being disgraced on account of her xenophobic views; rather, her comeuppance occurs when her sadomasochistic predilections are exposed. This messy narrative becomes entwined with Privilege proprietor Goldi (Anthony J Sharpe), who is revealed to be Brianna’s ‘slave’ in front of a One Nation-esque political rally in which the slogan ‘Put Australia First Again’ hangs above the crowd. Goldi’s plan to segregate patrons of his club based on their ethnicity further amplifies just how little Giannopoulos believes Australia has progressed as a country since the first film in the series was released.

Throughout Wog Boys Forever, it’s also possible to feel Giannopoulos pulling at the threads of anxiety that have come from the use of the word ‘wog’ in the titles of his films. He has suggested in interviews that if he put out The Wog Boy now, he would be ‘cancelled’ for using the term[9]See ‘Wog Boy Nick Giannopoulos Is Back in Town’, op. cit. – even though his work is a clear reclamation of the slur, much in the same way that the LGBTQIA+ community has reclaimed the word ‘queer’[10]See Juliette Rocheleau, ‘A Former Slur Is Reclaimed, and Listeners Have Mixed Feelings’, NPR, 21 August 2019, <https://www.npr.org/sections/publiceditor/2019/08/21/752330316/a-former-slur-is-reclaimed-and-listeners-have-mixed-feelings>, accessed 13 December 2022. – and suspects that this was a key factor in why Screen Australia declined to fund this new instalment: ‘My concern is that [a] young Nick Giannopoulos who has a crazy idea right now for a film like Wog Boy doesn’t have a chance.’[11]Nick Giannopoulos, quoted in Tim Clarke, ‘Wog Boys Forever: Candid Nick Giannopoulos Says Third Film in Series Was a Battle to Get to Big Screen’, PerthNow, 5 October 2022, <https://www.perthnow.com.au/entertainment/movies/wog-boys-forever-candid-nick-giannopoulos-says-third-film-in-series-was-a-battle-to-get-to-big-screen-c-8455700>, accessed 13 December 2022.

Screen agency funding aside, however, this argument doesn’t bear out: comedians like the Salanitri brothers and Manfre, for instance, have managed to echo Giannopoulos’ comedic stylings and forge a path through Australian culture with successful stage shows like Fifty Shades of Ethnic.[12]See Michael Lallo, ‘Australia’s New Wave of “Wog Humour” Is About Class as Much as Race’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 7 July 2018, <https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/tv-and-radio/australia-s-new-wave-of-wog-humour-is-about-class-as-much-as-race-20180627-p4zo2s.html>, accessed 13 December 2022. If Giannopoulos is concerned about the prospects of comedians who wish to push their comedy into areas that might make Anglo-Australian audiences uncomfortable, then he merely needs to heed his own protagonist’s advice:

There’s a line in Wog Boys Forever […] where I meet a young Congolese kid [Jean-Louis Mirindi], and he’s been ridiculed by his Aussie mates, and – without spoiling the movie – I have a crack at the mates and sort of put ’em down, you know, stand up for him [… and afterwards] I say, ‘Rubin, you know what I did when they used to call me a wog? I put “wog boy” on my numberplate, just to stick it up ’em.’ And he goes, ‘Oh, they let you do that?’ I say, ‘Yeah, of course.’ I said, ‘Mate, [in] this country, all new arrivals cop shit. It’s just the way it is. But what you’ve got to do is you’ve got to keep knocking on that door, real hard – and one day, they’ll let you in.’[13]Giannopoulos, quoted in ‘Wog Boy Nick Giannopoulos Is Back in Town’, op. cit.

Giannopoulos didn’t ask for permission to create his brand of comedy; rather, it arose from an absence of fear about what people thought or said about it. The Wog Boy’s success and enduring place in Australian culture – along with the desire of at least a portion of viewers to keep coming back for more – is testament to these films’ resonance with audiences who rarely get to see their communities represented on screen. But it’s also undeniable that attitudes and expectations among audiences and screen funding bodies alike have evolved over the past two decades. With more diverse and politically switched-on voices than ever stepping through the doorway that Giannopoulos helped force open, tactics beyond appeals to nostalgia may be required.

Endnotes

| 1 | See Murray Bramwell, ‘Community Announcement’, The Adelaide Review, no. 60, February 1989, p. 27, available at <https://murraybramwell.com/?p=1404>, accessed 13 December 2022. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Giannopoulos collaborated with Chris Anastassiades on the scripts of these two features; Wog Boys Forever marks his first solo feature screenplay. |

| 3 | The first two Wog Boy films made over A$11.4 million and A$4.9 million (not adjusted for inflation) at the Australian box office respectively. See Film Victoria, ‘Australian Films at the Australian Box Office’, 2011, pp. 15, 23, archived at <https://web.archive.org/web/20140209075310/http://www.film.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/967/AA4_Aust_Box_office_report.pdf>, accessed 13 December 2022. At the time of writing, five weeks into its theatrical run, Wog Boys Forever has earned a respectable A$2.9 million. See Jackie Keast, ‘BO Report: Black Panther: Wakanda Forever Dominates’, IF.com.au, 14 November 2022, <https://if.com.au/bo-report-black-panther-wakanda-forever-dominates/>, accessed 13 December 2022. |

| 4 | Nick Giannopoulos, in ‘Wog Boy Nick Giannopoulos Is Back in Town | Straight Talk Podcast | Mark Bouris’, YouTube, 29 September 2022, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ws9UhaOJHyM>, accessed 13 December 2022. A stereotypical representation of a Greek-Australian grocer created and embodied by Anglo-Australian performer Mark Mitchell, Con the Fruiterer was a popular recurring character on the sketch-comedy TV series The Comedy Company in the late 1980s and early 1990s; see Andrew Hornery, ‘Can Race Ever Be Fodder for Comedy? It All Depends on Who You Ask’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 31 May 2020, <https://www.smh.com.au/culture/celebrity/can-race-ever-be-fodder-for-comedy-it-all-depends-on-who-you-ask-20200527-p54wtd.html>, accessed 13 December 2022. |

| 5 | Giannopoulos, quoted in ‘Wog Boy Nick Giannopoulos Is Back in Town’, ibid. |

| 6 | See Thomas Mitchell, ‘“Where’s the Respect?”: Nick Giannopoulos on His Battle to Make Wog Boy 3’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 30 September 2022, <https://www.smh.com.au/culture/movies/where-s-the-respect-nick-giannopoulos-on-his-battle-to-make-wog-boy-3-20220929-p5bm11.html>, accessed 13 December 2022. |

| 7 | See Dora Houpis, ‘Forget Holden and Ford, the Early Greeks Drove Valiants’, Neos Kosmos, 27 February 2020, <https://neoskosmos.com/en/2020/02/27/dialogue/opinion/forget-holden-and-ford-the-early-greeks-drove-valiants/>, accessed 13 December 2022. |

| 8 | Quoted in Houpis, ibid. |

| 9 | See ‘Wog Boy Nick Giannopoulos Is Back in Town’, op. cit. |

| 10 | See Juliette Rocheleau, ‘A Former Slur Is Reclaimed, and Listeners Have Mixed Feelings’, NPR, 21 August 2019, <https://www.npr.org/sections/publiceditor/2019/08/21/752330316/a-former-slur-is-reclaimed-and-listeners-have-mixed-feelings>, accessed 13 December 2022. |

| 11 | Nick Giannopoulos, quoted in Tim Clarke, ‘Wog Boys Forever: Candid Nick Giannopoulos Says Third Film in Series Was a Battle to Get to Big Screen’, PerthNow, 5 October 2022, <https://www.perthnow.com.au/entertainment/movies/wog-boys-forever-candid-nick-giannopoulos-says-third-film-in-series-was-a-battle-to-get-to-big-screen-c-8455700>, accessed 13 December 2022. |

| 12 | See Michael Lallo, ‘Australia’s New Wave of “Wog Humour” Is About Class as Much as Race’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 7 July 2018, <https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/tv-and-radio/australia-s-new-wave-of-wog-humour-is-about-class-as-much-as-race-20180627-p4zo2s.html>, accessed 13 December 2022. |

| 13 | Giannopoulos, quoted in ‘Wog Boy Nick Giannopoulos Is Back in Town’, op. cit. |