Wash My Soul in the River’s Flow (Philippa Bateman, 2021) opens on a series of magnificent aerial shots of water, land and sky. This is Ngarrindjeri country, the homeland of Ruby Hunter: specifically, the locality of Goolwa in the Coorong,[1]Confirmed to author by publicist via email. the point where the Murray River meets the Great Australian Bight in south-east South Australia. It is dawn, and the sky is streaked with orange and pink, which is reflected kaleidoscopically on the surface of the river and sea. It is a spectacular, transcendent scene, shot with care and solemnity by cinematographers Bonnie Elliott and Maxx Corkindale.[2]Philippa Bateman, ‘Director’s Statement’, in Wash My Soul Productions, Wash My Soul in the River’s Flow press kit, 2021, p. 23.

The film then cuts to footage of Hunter and Archie Roach on stage. The pair are between songs, and Roach says:

Have you ever seen something so exquisite and beautiful, that you might be at least a little bit close to, that you feel you don’t deserve to stand in [its] light?

When Roach starts talking like this, the viewer might assume he is referring to the sublime scenes from the natural world that introduced the film. But no: he is talking about his life partner, musical collaborator and inspiration, Hunter. ‘That’s how I feel around Ruby sometimes,’ he says.

These moments establish two of this documentary’s key themes. The first is the spiritual resonance of Hunter’s Ngarrindjeri country, and the second is the deep, lasting and intimate bond shared by Hunter and Roach (the film’s tagline is ‘A Love Story in Song’). Indeed, perhaps these connections interweave with each other; perhaps the music the two created is the result of country and the pair’s love colliding. The film’s supremely graceful opening moments are charged with an additional emotional cadence with the knowledge that Hunter died in 2010.

Wash My Soul in the River’s Flow revisits a unique concert that Hunter and Roach gave in 2004 at Melbourne’s Hamer Hall, in which they presented a song cycle titled Kura Tungar – Songs from the River. A collaboration with the Australian Art Orchestra and renowned composer and musician Paul Grabowsky, the show was a multimedia presentation: in addition to Hunter and Roach singing their songs, the concert featured the couple telling stories from their lives, along with projections that showed natural landscapes and photographs from various points in their respective pasts. An audience of 2000 people attended the concert on that October night, and Kura Tungar went on to win the Helpmann Award for Best Australian Contemporary Concert in 2005.

Bateman, who later worked as an executive producer on acclaimed feature Jindabyne (Ray Lawrence, 2006), was tasked with filming the concert, together with its rehearsals and extensive interviews with Hunter and Roach. For reasons that the film never makes explicit, nothing was done at the time with these recordings; however, Bateman approached Roach in 2020 with the suggestion of revisiting the footage and releasing it as a documentary. Roach not only agreed to the project, but also facilitated the involvement of Hunter’s family and became a producer himself.[3]ibid., p. 17.

The result is a quiet, calm and simple film that is a profoundly important addition to the legacy of these two influential Indigenous musicians. The film features four distinct narrative strands: live-performance footage from the concert itself; behind-the-scenes recordings of rehearsals with the orchestra; Hunter and Roach in conversation with concert director Patrick Nolan; and those sweeping views of the Ngarrindjeri landscape. It also features occasional archival photos of Hunter and Roach from their younger days. Bateman presents all of these elements in a collage-like way throughout, at a steady, even pace that exhibits her controlled and understated filmmaking approach. Further contributing to this peaceful mood are the film’s frequent intertitles, which each linger on screen in silence for several seconds, in both English and Ngarrindjeri.

Seventeen years on from its genesis, Wash My Soul in the River’s Flow is relevant to a number of critical contemporary social issues. Chief among these is the place of the Indigenous population in modern Australia, and how, as a society, we are still yet to come to terms with the impact of the Stolen Generations, of which both Hunter and Roach are members. This is a subject that comes up frequently in Nolan’s interviews and, indeed, in the music – the film of course includes a performance of Roach’s most famous song, ‘Took the Children Away’.

Wash My Soul in the River’s Flow is relevant to a number of critical contemporary social issues. Chief among these is the place of the Indigenous population in modern Australia, and how, as a society, we are still yet to come to terms with the impact of the Stolen Generations.

Another issue the film brings up, holding added relevance when viewing the film today, is that of ecological (ill) health. The Murray-Darling Basin Plan has been one of Australia’s most contentious environmental topics in recent years,[4]See Jason Alexandra, ‘Murray-Darling Basin Damage Done, We Must Now Restore Trust in Its Management’, ABC News, 3 February 2019, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-02-03/murray-darling-basin-a-crisis-of-water-and-climate-law/10769722>, accessed 23 March 2022. in terms of both sustainability of wildlife and plant life[5]See ‘Plants and Animals’, Murray-Darling Basin Authority website, updated 24 September 2020, <https://www.mdba.gov.au/importance-murray-darling-basin/plants-animals>, accessed 23 March 2022. and water management.[6]See Kath Sullivan, ‘Federal Opposition Hints at Changes to Water Savings in Murray-Darling Basin’, ABC Rural, 28 February 2022, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/rural/2022-02-28/labor-holds-out-on-murray-darling-basin-plan-policy/100857968>, accessed 23 March 2022. The Coorong is part of the Murray-Darling Basin, but also faces its own specific threats.[7]See Erin Jones, ‘The Coorong’s Health Under the Spotlight as Report Finds Its Ecology Is in Decline’, The Advertiser, 8 November 2018, <https://www.adelaidenow.com.au/news/south-australia/the-coorongs-health-under-the-spotlight-as-report-finds-its-ecology-is-in-decline/news-story/2e3b6c547c714d50e60d651b921a6156>, accessed 23 March 2022. Bateman’s documentary features just one instance that directly deals with environmentalism, when Roach addresses care of land on stage during the concert, with particular reference to the Murray River, saying:

If we think of the rivers as veins, they are just as important as the veins in our bodies. And we know what happens to the veins in our bodies: they start to clog up when we put bad things into them – we’re in for a major heart attack or a stroke. And this being a physical land as well as a spiritual land, it’s in for a major heart attack or stroke if we’re not careful. So thank that blessed river, the Murray.

While these issues are surely at the forefront of the contemporary viewer’s mind when watching in 2022, they are arguably secondary to the film’s most arresting and important element: the music itself.

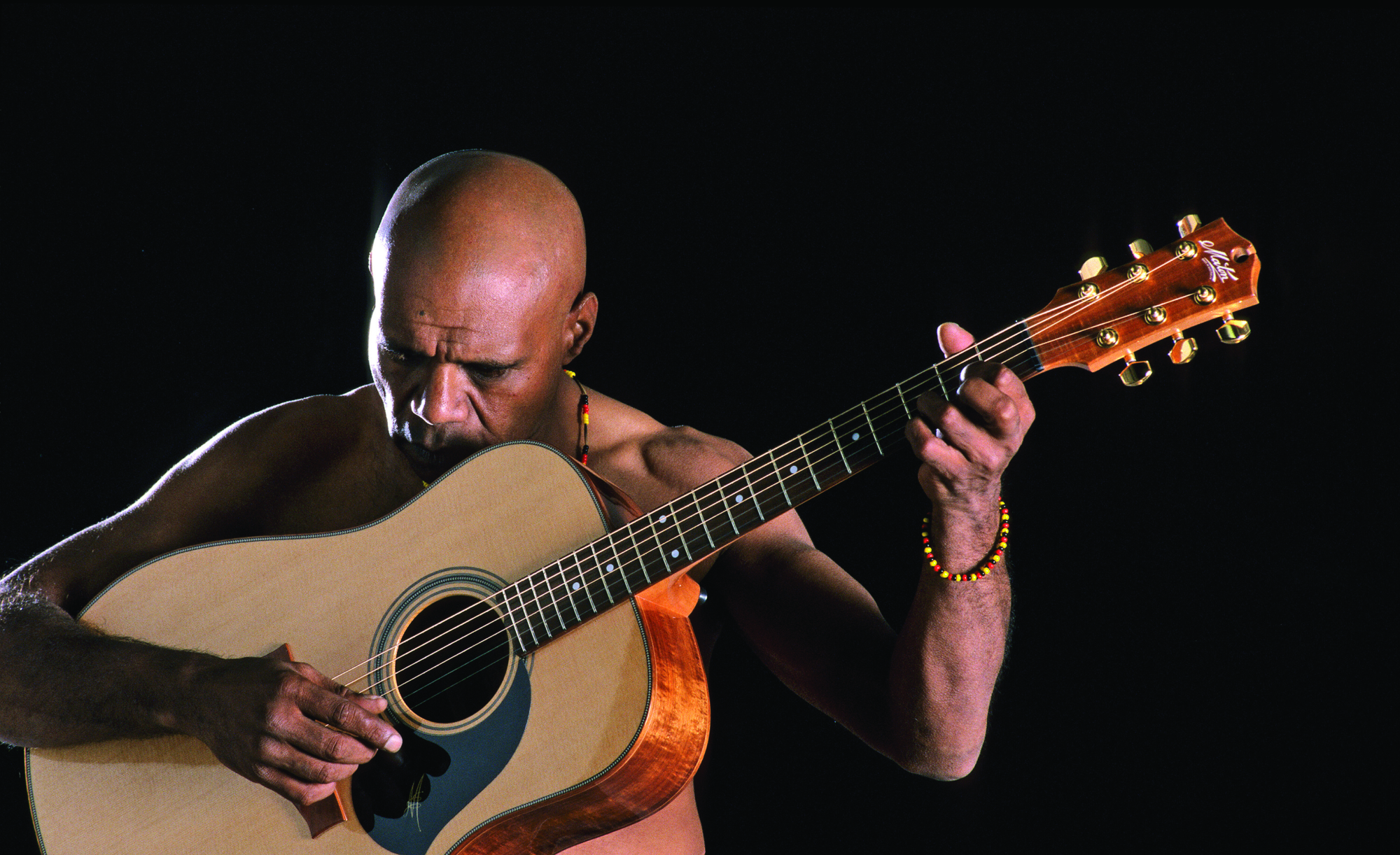

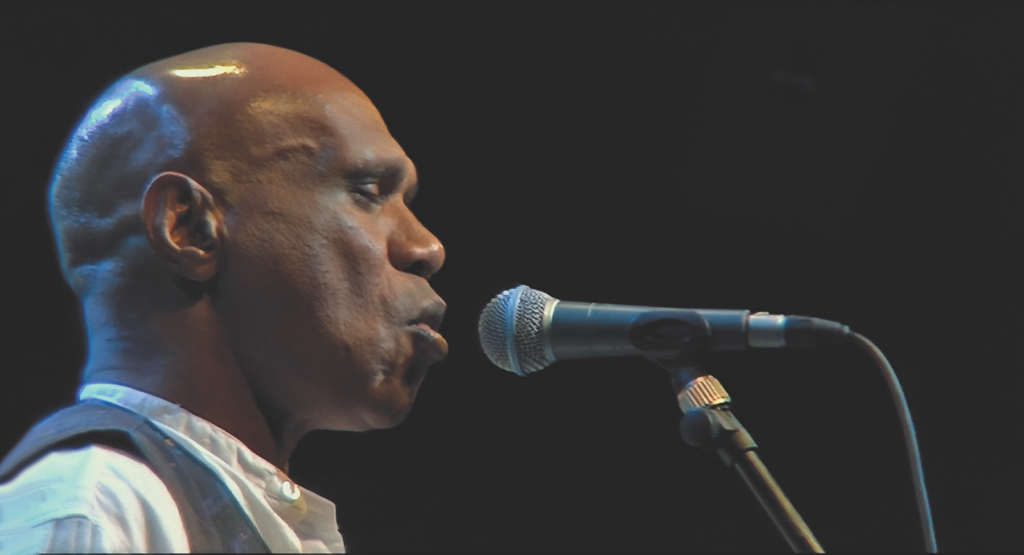

To start with, there is Roach’s voice, as it cascades over the orchestral backing on the film’s first song, ‘Into the Bloodstream’. The timbre of his vocals has a warm, husky depth comparable with American soul greats such as Al Green or Solomon Burke, a resonance that gives additional dimensions to the ‘soul’ of the film’s title.

Then there is Hunter’s own singular singing style, which almost defies description. The late performer was a sonic force of nature when opening her mouth to sing, and one of those rare vocalists for whom idiosyncrasy and peculiar delivery created an aesthetic all of its own. One review of the concert at the time described Hunter’s voice – which seems to be in the alto range – as ‘deep and velvety’,[8]‘Kura Tungar’, The Age, 19 October 2004, <https://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/art-and-design/kura-tungar-20041019-gdytpk.html>, accessed 23 March 2022. but this doesn’t touch on the uniqueness, the strength or the theatricality of her expression. If nothing else, Wash My Soul in the River’s Flow is a testament to Hunter’s singing, and her extraordinary originality.

Another striking musical aspect is the arrangements that the Australian Art Orchestra and Grabowsky give Hunter and Roach’s compositions. Mostly, the songs adopt classic American styles of the twentieth century. ‘Into the Bloodstream’ is immersed in gospel; ‘Took the Children Away’, in jazz; ‘Old So & So’ employs the instrumentation of big band. Elsewhere, Roach sings ‘Nopun Kurongk’, which has an experimental, minimalist feel, driven by screeching and jumpy violin. Hunter’s performance of ‘Daisy Chains, String Games and Knuckle Bones’ is particularly intriguing – a chirpy number that feels almost like a show tune (the song ‘I Wanna Be Loved by You’, made famous by Marilyn Monroe, comes to mind), yet deals with the trauma of being taken from her family and her ‘Coorong home’ in early childhood. This pattern of juxtaposing sprightly music with shattering subject matter is a feature of many of the songs performed in the film.

Overall, the arrangements are an eclectic mix, with Grabowsky and the orchestra an imaginative but never intrusive foil for Hunter and Roach’s simple songs. ‘I like singing to the way it’s arranged with the orchestra,’ Roach says at one point. ‘It lifts me up more; it takes me above it – it takes me above [the song’s] circumstance and puts me somewhere else.’

A consistent characteristic of both Roach’s and Hunter’s songwriting is repetition. Songs such as ‘Into the Bloodstream’, ‘Daisy Chains, String Games and Knuckle Bones’ and ‘Coolamen Baby’ see their titular lines repeated over and over, to the point that the songs feel like mantras. This meditative – perhaps hypnotising – quality is picked up on in the documentary by Grabowsky when he says of the song cycle, ‘There is a gentle flow from song to song that evokes a river.’ And this description might also be applied to the way Bateman has crafted the film overall. The writer/director has achieved an exquisite, ethereal stillness that persists throughout, in which music sits harmoniously alongside silence, and in which David Attenborough–like nature cinematography exists calmly alongside accounts of the crimes committed against Indigenous communities.

Nolan’s interviews – particularly with Hunter – are similarly remarkable, to the point that the film can also be regarded as a contribution to the oral history of the Stolen Generations. At one point, when recalling her memories of being stolen in 1964, Hunter talks about how she was laughed at by white people for the fact that, as a little girl displaced from her family, she did not know how to put on clothes:

That was the first time we had to wear clothing – the first time we had to put on shoes, socks, little panties, petticoats. [I] didn’t know how to put them on […] They were laughing at me getting dressed. I walked out with pants on me head. ‘What do you do with these?’

Hunter’s profile as a musician will be forever linked with Roach, whom she first met as a teenager, but Bateman’s film feels like a particular reminder of her towering artistic presence in Australia’s national culture. She died at fifty-four, and the gap she has left remains significant.

The performance of a song cycle has, traditionally, involved a distinct etiquette. Audiences are often requested not to applaud between songs, and to wait until the entire cycle has concluded before showing their appreciation.[9]See Brooke Kroeger, ‘When Applause Isn’t Welcome’, The New York Times, 20 August 2000, <https://www.nytimes.com/2000/08/20/nyregion/soapbox-when-applause-isn-t-welcome.html>, accessed 23 March 2022. This has certainly been my experience when viewing a song cycle performance, and, based on several moments in Wash My Soul in the River’s Flow, it appears to have been the case for Kura Tungar. The film ends with the pent-up Melbourne audience unleashing rapturous ovation for Hunter and Roach, following a long, ambitious and cacophonous rendition of the song that gives the film its title. It’s a rare moment of high energy and emotional fever pitch in this otherwise contemplative and tranquil work.

But during and after this noisy cathartic release, we return to those scenes of Goolwa in the Coorong. This time it is dusk, and the water holds a different kind of serenity. The closing of the day reflects the closing of a chapter that took seventeen years to unfold. The film that has emerged from that process is an artefact of national importance, and deserves to be widely seen.

Endnotes

| 1 | Confirmed to author by publicist via email. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Philippa Bateman, ‘Director’s Statement’, in Wash My Soul Productions, Wash My Soul in the River’s Flow press kit, 2021, p. 23. |

| 3 | ibid., p. 17. |

| 4 | See Jason Alexandra, ‘Murray-Darling Basin Damage Done, We Must Now Restore Trust in Its Management’, ABC News, 3 February 2019, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-02-03/murray-darling-basin-a-crisis-of-water-and-climate-law/10769722>, accessed 23 March 2022. |

| 5 | See ‘Plants and Animals’, Murray-Darling Basin Authority website, updated 24 September 2020, <https://www.mdba.gov.au/importance-murray-darling-basin/plants-animals>, accessed 23 March 2022. |

| 6 | See Kath Sullivan, ‘Federal Opposition Hints at Changes to Water Savings in Murray-Darling Basin’, ABC Rural, 28 February 2022, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/rural/2022-02-28/labor-holds-out-on-murray-darling-basin-plan-policy/100857968>, accessed 23 March 2022. |

| 7 | See Erin Jones, ‘The Coorong’s Health Under the Spotlight as Report Finds Its Ecology Is in Decline’, The Advertiser, 8 November 2018, <https://www.adelaidenow.com.au/news/south-australia/the-coorongs-health-under-the-spotlight-as-report-finds-its-ecology-is-in-decline/news-story/2e3b6c547c714d50e60d651b921a6156>, accessed 23 March 2022. |

| 8 | ‘Kura Tungar’, The Age, 19 October 2004, <https://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/art-and-design/kura-tungar-20041019-gdytpk.html>, accessed 23 March 2022. |

| 9 | See Brooke Kroeger, ‘When Applause Isn’t Welcome’, The New York Times, 20 August 2000, <https://www.nytimes.com/2000/08/20/nyregion/soapbox-when-applause-isn-t-welcome.html>, accessed 23 March 2022. |