Goa–Gunggari–Wakka Wakka Murri writer, director and actor Leah Purcell has lived with the story of Molly Johnson for a long time.

She remembers encountering Henry Lawson’s 1892 short story The Drover’s Wife as a small child in the mid 1970s when she was first learning to read and write, practising in the margins of her schoolbooks. As it turns out, Lawson’s tale of a country woman who – having been left alone while her husband is away driving sheep – has to defend her young children from a venomous snake held more appeal than the simpler, more straightforward exploits of Dick, Dora, Nip and Fluff.[1]The respective boy, girl, dog and cat protagonists of ubiquitous mid-century Australian children’s book series The Happy Venture Readers.

‘I think it was because it’s the first story that I could visualise myself being in,’ she recalls.

There was no father-figure around when I was growing up, so my mother was the man: she was the mother, she was the father, she was my hero. And I did look at myself as the man of the house; I was there to protect her.

We lived in the country; we had a combustion stove; we had a woodheap – my mother taught me to split logs and to pack a woodheap, and she would say, ‘Pack it tight, because we don’t want snakes getting in under there.’

All those elements are present in Lawson’s brief, evocative story, but the drover’s wife of Purcell’s imagination is a more complex figure than Lawson’s unnamed protagonist (the name ‘Molly Johnson’ is Purcell’s invention). Over the years, Purcell has expanded, reinvented and recontextualised The Drover’s Wife, reframing the sparse story through the lens of her own experience as an Indigenous woman. She wrote and starred in an acclaimed stage version that debuted at Sydney’s Belvoir St Theatre in September 2016 under the direction of Leticia Cáceres, and her novel of the same name was published by Penguin Random House in late 2019. And now – its wide release having been much delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic since it premiered at the SXSW Film Festival in March 2021 – her feature debut as writer/director, The Drover’s Wife the Legend of Molly Johnson, will at long last be seen by Australian audiences outside the festival circuit. It has been a long road, and Purcell is trepidatious but excited:

I can’t wait for Australia to see it. I want Australia to own this. I want the audience to take responsibility for Molly Johnson. I gave birth; it’s up to the audience now to protect her and push her to great heights. I believe in this story – it is a story for all.

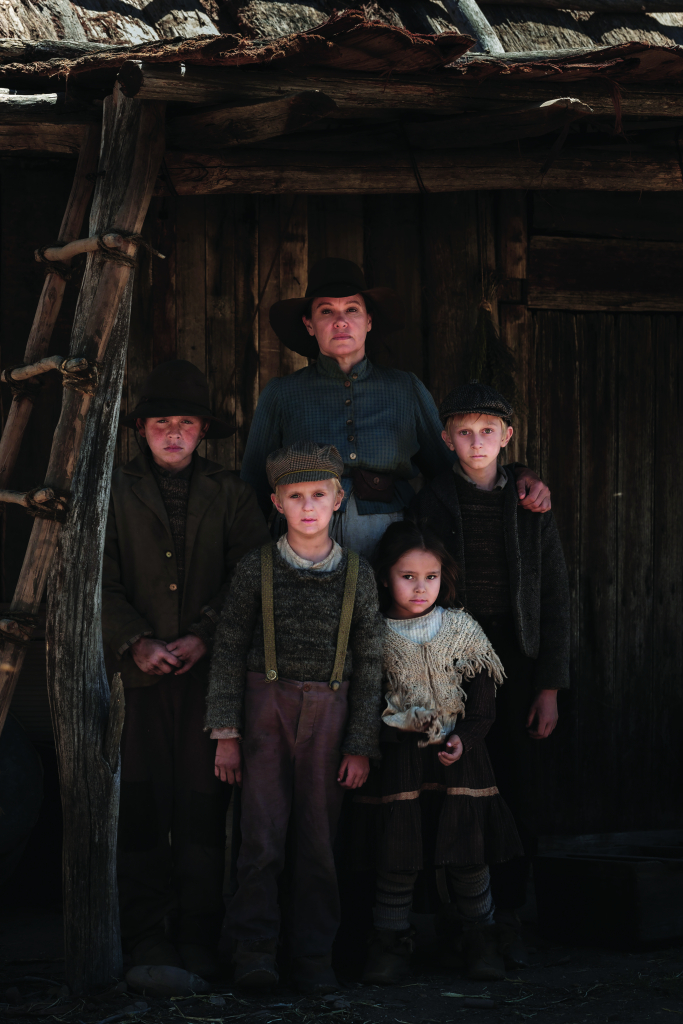

And yet it is also a very specific story. Set in the Victorian Alps, The Drover’s Wife the Legend of Molly Johnson sees Purcell once again embodying the titular protagonist. As in Lawson’s original tale, she’s looking after her handful of young children while her husband is apparently working away; and, like Lawson’s character, she’s a hard-nosed, pragmatic woman, shaped by the hardships inherent in carving out a life in the nineteenth-century wilderness. But Purcell’s Molly is, like Purcell herself, Indigenous; the short story’s character of Black Mary – ‘the “whitest” gin in all the land’,[2]Henry Lawson, ‘The Drover’s Wife’, in Lawson, When the Billy Boils, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1896, p. 132. who acts as midwife when the drover’s wife is giving birth – is here reimagined as Molly’s mother, who died in childbirth, taking Molly’s connection to her Aboriginal heritage with her.

Purcell’s film is, in part, the story of Molly discovering her true identity – a process that is catalysed by the arrival of an Indigenous fugitive, Yadaka (Rob Collins). While Lawson’s heroine has to deal with a snake in the woodpile, Purcell’s must contend with a man wanted for murder who is seeking refuge on her remote farm. Molly initially threatens him, saying ‘I’ll shoot you where you stand, and I’ll bury you where you fall.’ Yadaka is a more complex, and ultimately altruistic, figure than he initially seems, however; his crime, he tells her, is ‘existing whilst Black’.

The drover’s wife of Purcell’s imagination is a more complex figure than Lawson’s unnamed protagonist (the name ‘Molly Johnson’ is Purcell’s invention).

In Purcell’s film, Yadaka is a distillation of two figures from the Lawson story: the snake that is the focus of the action and an unnamed ‘stray blackfellow’, ‘the last of his tribe and a King’, who is hired to collect wood but does a haphazard job of it.[3]ibid., p. 136. Whereas these figures are respectively antagonistic and comical, Yadaka proves heroic, teaching Molly and her children about their Indigenous heritage. He also, to a degree, fulfils the function of Lawson’s Black Mary, helping the pregnant Molly give birth.

‘As an Indigenous woman, I want an opportunity to, if I can, share an understanding of Indigenous issues in life using my family stories,’ Purcell explains.

I wanted to find a way to bring that Aboriginality into it. I thought instead of a black snake, let’s have a Black man and let that man be amazing – because, up until this time, well, you never saw that in films. The Black man was always downtrodden, or he was the bad guy. But my uncles and my nephews are great fathers, and great grandfathers. I wanted to go, ‘No, the Black men in my lives are my heroes,’ and I wanted him to be a hero.

Heroes require villains. And although the odd specific antagonistic figure hovers into view – Harry Greenwood turns up as a malevolent bush larrikin at one point – the actual evils Molly faces are largely systemic, hierarchical, colonial. Indeed, they are still with us; as the rumour that Molly is not white – or not wholly white – spreads, the local minister (Bruce Spence) and his sister (Maggie Dence), along with the district judge (Nicholas Hope), conspire to have her children taken into custody, in a deliberate foreshadowing of the stolen generations of the twentieth century. And then there’s Joe, Molly’s absent and unseen drover husband, who is eventually revealed to have been physically and sexually abusive. As it eventuates, he is not away droving; Molly killed him in self-defence and disposed of the body, an act that sets up the film’s devastating climax in which her crime is discovered and she is hanged for murder.

Purcell complicates matters by giving us some more sympathetic white characters in the form of new local police commander Sergeant Nate Klintoff (Sam Reid) and his wife, nascent feminist Louisa (Jessica De Gouw), whom we meet when they stop by the Johnson homestead for food and shelter en route to the sergeant’s new posting. Louisa, an ardent campaigner for the rights of women, befriends and supports Molly, going so far as to offer to house her children and ultimately organising a protest at her execution. The irony is that her husband, portrayed as an empathetic and dutiful man, is in the end the one chiefly responsible for Molly’s death. While it’s clear – or at least probable, given we never see the act – that Joe’s killing was justified, the sergeant is unmoved. ‘This land needs law, not a moral compass,’ he declares. He’s acting not as an individual but as an agent of the law, of the colonial government. It adds a note of queasy, impersonal, fatalistic horror to the proceedings; Molly’s death comes not through the agency of some hissable villain, but through the cold machinations of bureaucracy. In the face of such lack of sentiment, Louisa’s ardent but ineffectual advocacy – which culminates with her and her allies waving signs and placards while the noose is slipped around Molly’s neck – feels farcical.

And yet The Drover’s Wife ultimately refutes hopelessness, rejecting the grim denouements offered by recent films such as Warwick Thornton’s Sweet Country (2017) and Jennifer Kent’s The Nightingale (2018), even though it too climaxes with the brutal death of its Indigenous protagonist. The second part of the title, the Legend of Molly Johnson, is as much a nod to the western genre trappings of the film as a declaration of intent. With her death, Molly ascends not just into myth, but into dream.

Is that literal? It’s difficult to say as a white viewer, but Purcell avers that the entire narrative structure of the film is deeply rooted in Dreamtime storytelling traditions. ‘I wanted to incorporate our culture – our Dreaming structure,’ she says. ‘I actually structured this film on the Dreaming.’ As such, Molly’s story is not linear, ending with the grim finality of her death, but cyclical: she becomes part of something greater than her mortal life as her story is told. There’s a metatextual element to this, with the legend of Molly Johnson in the film both reinforcing and being reinforced by the Legend of Molly Johnson the film. The act of telling the story both empowers the story and draws from its power – a kind of creative ouroboros blurring the borders of fiction, deliberately making a myth.

The act of telling the story both empowers the story and draws from its power – a kind of creative ouroboros blurring the borders of fiction, deliberately making a myth.

A subplot, seemingly of little consequence at first, demonstrates this exact process for us through the course of the film. As in Lawson’s short story, when a wild bullock strays onto the Johnson farm, Molly doesn’t hesitate to kill it in order to both protect and feed her children. It’s a dramatic but throwaway moment, yet one that fascinates Molly’s eldest child, twelve-year-old Danny (Malachi Dower-Roberts), who later tells the story of the incident to Yadaka. Yadaka, in his turn, enacts the story of the bullock as a ritual dance, immortalising it. ‘Molly experiences it, Danny witnesses it, Danny shares it with Yadaka and he embellishes it with movement,’ Purcell says.

The ultimate evolution of the bullock story comes much later in the film’s denouement as Danny, now a grown man, re-enacts it for his own children. A random incident has now become part of the storytelling fabric of the culture. ‘That’s how our culture survives,’ Purcell explains.

That circular pattern. Some Indigenous mob that I showed it to got so excited to see that. ‘That’s our Dreaming,’ they said. ‘Someone’s actually finally put our structure of how our Dreaming stories exist up on screen.’

Purcell has not just done this in the film The Drover’s Wife the Legend of Molly Johnson, but she has also done it for Lawson’s original story, The Drover’s Wife. In recontextualising this brief tale of colonial life into a meditation on Indigenous female identity across many years and multiple media, she has made it greater than it was, elevating it – if not to the level of myth, then certainly to a higher plateau in the Australian cultural firmament.