At the time of writing, ‘raw water’ can be priced as much as A$19 per gallon.[1]Yasmin Noone, ‘Raw Water: Is It a Healthy Trend or a Dangerous Fad?’, SBS Food, 5 March 2018, <https://www.sbs.com.au/food/health/article/2018/03/05/raw-water-it-healthy-trend-or-dangerous-fad>, accessed 22 May 2018. Its proponents say that filtered water – the kind we get from taps – is stripped of essential nutrients and contaminated with pollutants like lead. They also speak of the sensual quality of the product: its texture, the way it moves on the palate, how the individual characteristics of each natural spring change the flavour of the water. They sniff the water before they drink it, probably.[2]For more on the movement, see Jen Kirby, ‘What to Know About the “Raw Water” Trend’, Vox, 4 January 2018, <https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2018/1/4/16846048/raw-water-trend-silicon-valley>, accessed 22 May 2018.

In the US – where the movement originated, and where the use of lead in water systems has been banned by Congress – some areas nevertheless see water fed through old, crumbling lead pipes as a result of improper spending or, perhaps, an unwillingness to maintain basic infrastructure.[3]ibid. It’s difficult to make sense of a world where one can develop poisoning from merely turning on the tap and drinking what comes out,[4]In Flint, Michigan, for instance, up to 8000 children have been exposed to lead, which could ‘have lifelong effects on their brain and nervous systems’; see Libby Nelson, ‘The Flint Water Crisis, Explained’, Vox, 15 February 2016, <https://www.vox.com/2016/2/15/10991626/flint-water-crisis>, accessed 22 May 2018. and there’s a loneliness to the idea that the people who have the resources to help you would rather use them for profit.

Indeed, there’s a pervasive hopelessness polluting our society – and it is arguably, by and large, affecting the young more than anyone else. In South Australia, despite statewide improvements in the rate of joblessness, youth unemployment is the highest in the country (at 17.5 per cent as of August 2017), particularly as manufacturing leaves the state.[5]David Washington, ‘SA Jobless Rate Drops, No Longer the Worst’, InDaily, 17 August 2017, <https://indaily.com.au/news/2017/08/17/sa-jobless-rate-drops/>, accessed 22 May 2018. The realisation that we are barred from the lives enjoyed by our parents – and by the teenagers we see in movies, so hopeful and full of potential – is a tough one. As traditional structures crumble, what happens to the young?

The teen movie has always concerned itself with the exploration of adolescence as a period of metamorphosis, of liminality. Its protagonists negotiate the space between childhood and adulthood as a crisis that they must overcome. Anthropologist Arnold van Gennep wrote that all humans experience ‘life crises’[6]Arnold van Gennep, cited in Anna Backman Rogers, American Independent Cinema: Rites of Passage and the Crisis Image, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2015, p. 3. at the points of birth, puberty, marriage and death, and this denotes a process, in the words of academic Anna Backman Rogers, of ‘becoming-other’: ‘the ritual subject goes through a period of instability in which he/she is subjected to various trials and his/her former self is effaced’.[7]Backman Rogers, ibid. In the context of the narrative arc of the teen movie, then, this can be understood as a character’s coming of age.

In his searing film Youth on the March (2017), Mike Retter shifts the liminality inherent in the teen-movie protagonist’s experience to the world surrounding them – and, in doing so, creates a film that offers an unflinching depiction of Australian adolescence. ‘Youth on the March is based on a very typical suburban adolescence,’ says Retter, ‘smoking pot with friends, not really doing much with your life and more serious stuff, issues with parents, sexuality.’ He continues:

I didn’t want to do it in a typical gritty way, but a sort of baroque, romantic or stylised way […] the way it actually feels to live in the suburbs in Adelaide, rather than depicting it the way a more middle-class filmmaker may observe the suburbs. I wanted to capture that fear of being young – just like [how] walking down the street at night gives you some kind of adrenaline rush.

Shot vertically in 9:16, as if using a smartphone, and with a fragmentary and expressionistic narrative, Youth on the March aims to capture the pervasive mood of growing up in a world where escapism quite often means survival.

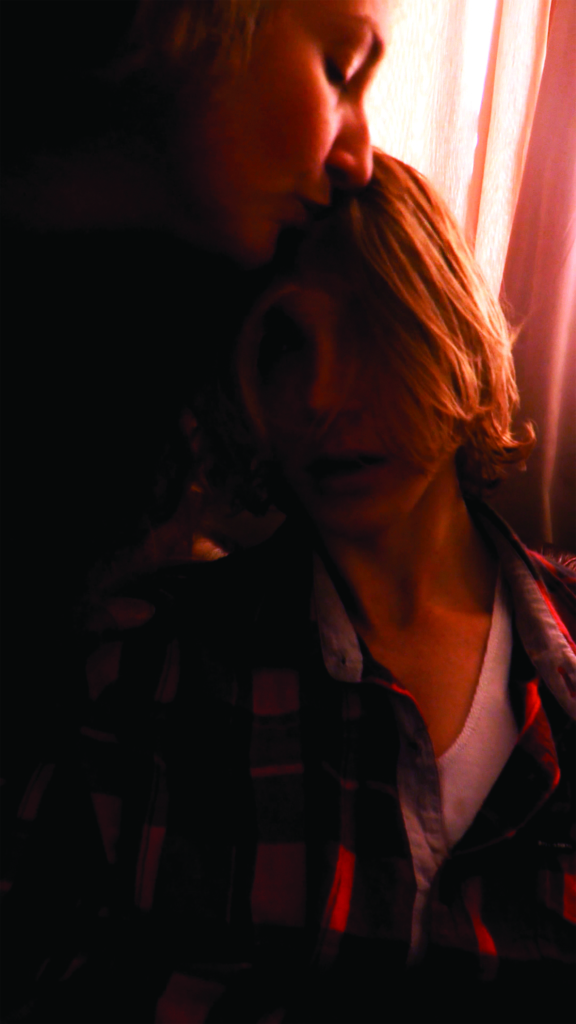

The result is a teen movie with a difference, capturing – in Retter’s words – ‘that ecstasy of the simple things involved in just hanging out’. Shot vertically in 9:16, as if using a smartphone, and with a fragmentary and expressionistic narrative, Youth on the March aims to capture the pervasive mood of growing up in a world where escapism quite often means survival. This visual technique imbues the film with an intense closeness to its subjects: the titular disaffected youth, whom society too often ignores. The central youth in question is Gill (Ben Ryan), a teenager from the suburbs who doesn’t know his dad and lives with his mum (Stefanie Rossi). She works a lot; he steals her cigarettes, smokes a lot of pot, and spends a ton of time fucking around with his friends in car parks and alleys around the city. It’s an experience close to the heart of Retter, who describes the film as ‘very autobiographical’.

I moved out of home when I was seventeen, and I was living on a couch with two other boys in the room. To our right and left were similar scenarios of young people in youth accommodation […] so we smoked, drunk alcohol, took mushrooms, went around the corner to the video shop, stole stuff […] Just not really doing anything constructive.

The filmmaker explains that, with Youth on the March, he ‘wanted to make a film with a different politics’.

I don’t think there are clear answers to things. I wanted to make something with a different perspective that wasn’t romanticising the wrong things, but not looking down on the characters and their lives and their choices. I find that Australian film is very sterile when it talks about suburbia: it’s very anthropological and sees it as a great opportunity to ram university ideology into a film. I wanted to make a film that was not connected to that at all because I think it’s authoritarian.

While most teen movies simplify the adolescent experience in an attempt to provide the audience with a neat resolution – for instance, through romance or the character ‘fitting in’ to social norms (like getting into university) – Retter’s film is a love letter to the moments in between, the moments of boundless exploration that adolescence affords us. In turn, Youth on the March’s narrative challenges conventional structure, with little plotting apart from a loose love story. Visually, the film rides the highs and lows of Gill’s moods: when he’s high, it becomes slow and paranoid, with zooms that get uncomfortably close to him; when he’s horny, it becomes dark and dank, lit only by a laptop screen. We’re given a series of suburban tableaux that are as awkward, intimate and insular as adolescence itself. Form, for Retter, follows content.

Film scholar Adrian Martin observes that the fundamental failings of Australian teen movies lie in imagination and ambition, citing that they

lack that sense of cinema which even the modest hits of the [teen movie] genre show off in abundance – often a cinematic inventiveness achieved precisely within low-budget technical and financial means. As is so often the case, Australian films, frozen at plot development stage, become fixated primarily on the literary and theatrical values of plot and character – at the expense of film style, which ends up being considered and treated as mere window dressing, at best an enhancement or underlining of the literary themes in the script, rather than the primary substance of the cinematic experience for viewers. The divorce between form and content breeds monsters …[8]Adrian Martin, ‘Live to Tell: Teen Movies Yesterday and Today’, Lumina, issue 2, 2010, p. 8.

Martin’s sentiments are echoed by Retter, who developed a passion for filmic storytelling outside of traditional structures. ‘I never went to film school, so the education came from running a non-profit video shop called The Port Film Co-op. It was probably the first time I felt a real camaraderie in film since working in community television,’ he says.

People would come in and borrow movies, then stay a while and talk about them with me and other people from the community. It became a really special place for a lot of people, and we all learned and fell in love with cinema. Sharing the passion [… and] that real organic film culture, you realise that you couldn’t care less about the institutions because you realise that you could just do it all yourself. Together. My best friends and collaborators came out of that experience.

Being an outsider – and creating work about outsiders – has given Retter the ability to pinpoint some of the key failings within the Australian film industry. ‘Aussie films don’t have a variety of points of view. They look the same, and it’s almost like every film uses one cinematographer.’ He continues:

I’m not a fan of [Jean-Luc] Godard, but I do like a lot of things he said. One [of those] is that his films are criticism […] As a film lover, I want to make films as honestly as I can. But, in a way, it’s a criticism of the current mode of filmmaking in Australia.

The best thing I can do as a filmmaker is to do what they do in the rest of the world: bypass the system. Make your film on your credit card – do it yourself. It just takes too long waiting around for eight years for something to get funded or get recognised, and I don’t like waiting around. Sometimes you want to film something in eight months because you know what the weather is going to be like and that’s what you want to shoot. The next film I’m making is going to have a lot of rain, so I’ve just decided to film it in real storms, which is free and [offers] great production value.

According to Retter, we are ‘very spoiled in Australia’, which ‘creates a sense of comfort in who we are’ that can stifle the drive to create.

We very rarely have this as a public conversation […] The solutions are always [that of] throwing more money at the problem or trying to recapture past success by following certain formulas. Michael Rowe, who made the film Early Winter [2015], said that Australian film bureaucracies are afraid of directors; they’re afraid of people who want to make stuff, [so] he’s made all his films overseas. The culture [here] does push people overseas, which causes brain and talent drain. And it’s such a shame.

As traditional structures crumble, what happens to the young? What do they do? As the case of Retter shows, they don’t drink or buy into raw water. They experiment. They smoke joints and fall in love and dream of a world that’s better, even though it doesn’t seem like there could be one for people like them. What Youth on the March shows us, in its messy way, is that contemporary Australian film – like Gill and his friends – is stuck. Perhaps it, too, is caught in a liminal space, trying to work out what it will become next, especially after the grand successes of its Australian New Wave forebears. But it doesn’t have to be. Maybe it needs to be messier, to experiment and have its period of hedonistic adolescence, or maybe it just needs a shot of youthful exuberance. ‘Cinema is a way more exciting artform than we give it credit for,’ says Retter. ‘People are dying for stories and want to see themselves on screen. We should make it exciting for them.’

Endnotes

| 1 | Yasmin Noone, ‘Raw Water: Is It a Healthy Trend or a Dangerous Fad?’, SBS Food, 5 March 2018, <https://www.sbs.com.au/food/health/article/2018/03/05/raw-water-it-healthy-trend-or-dangerous-fad>, accessed 22 May 2018. |

|---|---|

| 2 | For more on the movement, see Jen Kirby, ‘What to Know About the “Raw Water” Trend’, Vox, 4 January 2018, <https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2018/1/4/16846048/raw-water-trend-silicon-valley>, accessed 22 May 2018. |

| 3 | ibid. |

| 4 | In Flint, Michigan, for instance, up to 8000 children have been exposed to lead, which could ‘have lifelong effects on their brain and nervous systems’; see Libby Nelson, ‘The Flint Water Crisis, Explained’, Vox, 15 February 2016, <https://www.vox.com/2016/2/15/10991626/flint-water-crisis>, accessed 22 May 2018. |

| 5 | David Washington, ‘SA Jobless Rate Drops, No Longer the Worst’, InDaily, 17 August 2017, <https://indaily.com.au/news/2017/08/17/sa-jobless-rate-drops/>, accessed 22 May 2018. |

| 6 | Arnold van Gennep, cited in Anna Backman Rogers, American Independent Cinema: Rites of Passage and the Crisis Image, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2015, p. 3. |

| 7 | Backman Rogers, ibid. |

| 8 | Adrian Martin, ‘Live to Tell: Teen Movies Yesterday and Today’, Lumina, issue 2, 2010, p. 8. |