‘Friends and flukes have been the making of me.’ So says storied Australian Labor Party (ALP) speechwriter Graham Freudenberg in Ruth Cullen’s The Scribe (2018). Cullen’s documentary is a portrait of the man and his musings on the role that rhetoric has played in politics, with a brief incursion into how that might be changing. The result is a hybrid of sorts: a filmic profile of Freudenberg and an insider’s account of a few tumultuous decades in Australian politics.

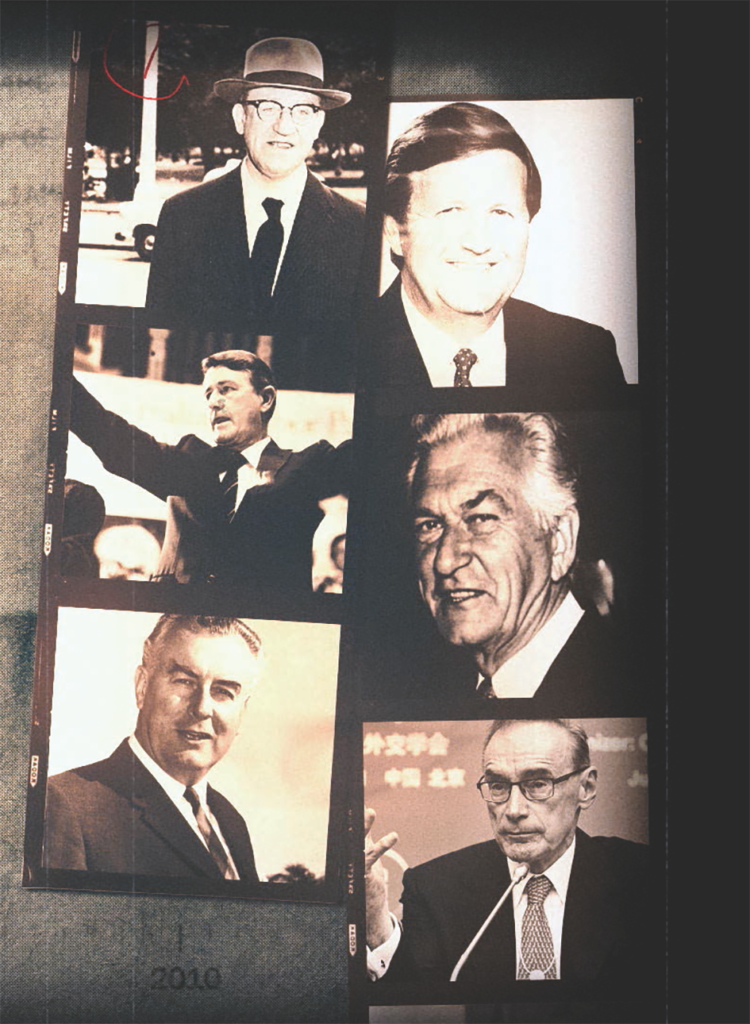

Proclaimed by journalist Laurie Oakes to be ‘the greatest speechwriter this country has produced’,[1]Laurie Oakes, ‘Politicians Have Lost the Art of Making Great Speeches Thanks to Sound Bites’, The Herald Sun, 3 June 2017, <https://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/opinion/laurie-oakes/politicians-have-lost-the-art-of-making-great-speeches-thanks-to-sound-bites/news-story/ab733b3d583797b4e19124e227e6d8cb>, accessed 13 February 2019. Freudenberg – known as ‘Freudy’ to his colleagues – crafted words that were spoken by an assortment of ALP heavyweights, beginning in 1961 with then–federal opposition leader Arthur Calwell and ending in 2005 with the resignation of New South Wales (NSW) premier Bob Carr. As a teenager, the documentary tells us, Freudenberg read voraciously and, precociously modelling himself after nineteenth-century British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli (whose biography he read at age ten), he embarked on a journalism career with a grand plan of eventually moving into politics.

As he ‘never had the great hunger for a story that really makes a great reporter’, he notes in The Scribe, he made the shift across after hearing about a press-secretary job in Calwell’s office. He landed the gig, which initially involved just liaising with the Canberra Press Gallery, writing press releases and keeping up with information. But he quickly found himself writing the ALP leader’s speeches, even though doing so was not in the original position description.

Freudenberg recounts that he learned about the job midway through a party and raced out to immediately apply. Crucially, he found out about the opportunity at the beginning of the night. ‘If the conversation hadn’t occurred early in the party,’ he says, ‘before I was blotto, the whole course of my life would have been completely different.’ This frank admission is not the last time alcohol comes up in The Scribe; indeed, beer is something of a recurring theme. ‘Drink, of course, did play a large part in the political affairs of this nation,’ Freudenberg observes, describing how parliamentarians and their staff frequently find themselves stuck in the same building for hours on end until the house adjourns, often well after midnight.

The speechwriter identifies beer as his ‘great love’, and indeed it played a vital role in several key moments in his political career. As former prime minister Bob Hawke – interviewed in the film as one of a few recurring talking heads – muses, he and Freudenberg ‘sculled a few together. It was during one of those sessions that he said I was going to be the next prime minister, and that he wanted to work with me.’ Freudenberg even took to measuring the difficulty of his speeches by how much beer he consumed while writing them. ‘At a certain stage in most speeches, I needed some liquid refreshments,’ he says. ‘The average speech [is] a six-can job. A great speech might be a thirteen- or fifteen-can job.’

Yet, as shambolic as that sounds, Carr – another talking head – notes that Freudenberg never once missed a deadline. So trustful of his work was Carr that the two didn’t even meet to discuss the contents of big speeches before Carr would deliver them. He says he trusted ‘the depth of [Freudenberg’s] history, and the diamond-hard quality of his memory’; he merely ensured his speechwriter had the necessary tools for the job, then would receive the speeches by fax.

As with elsewhere in the film, Cullen shows little interest in critically evaluating her talking heads’ claims. With most of them being ALP insiders, we’re left to take these claims at face value and without much in the way of context. As it is, the moments when The Scribe gets more critical of rhetoric in politics are when Freudenberg himself reflects.

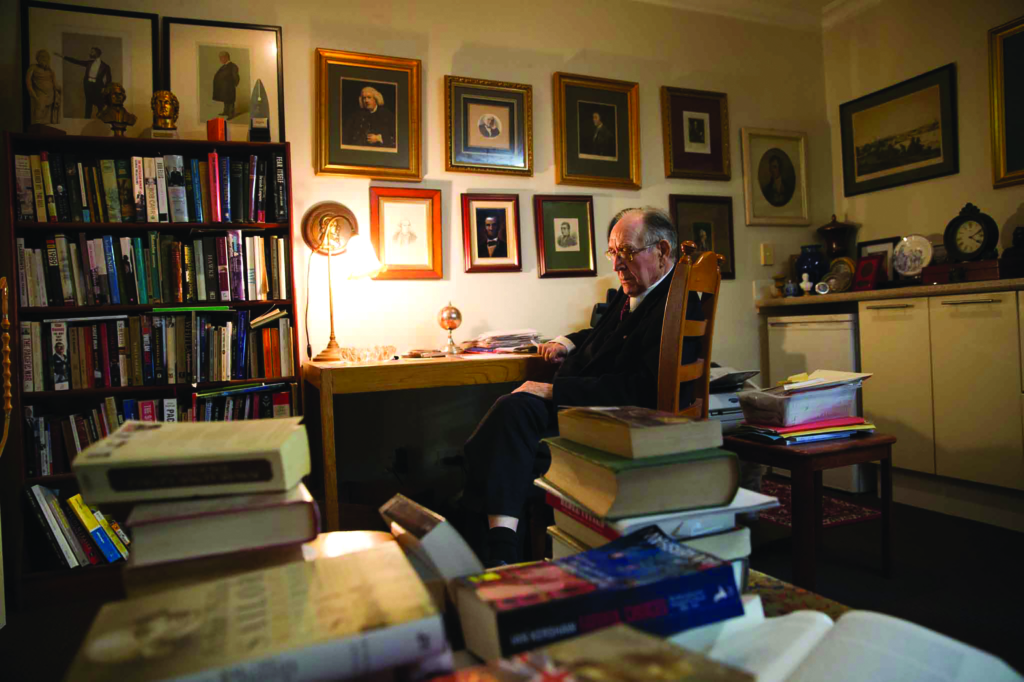

From the evidence presented in The Scribe, we encounter a Freudenberg with an abiding respect for the canonical figureheads of his field – particularly former US president Abraham Lincoln, whose portrait hangs on his wall at home. Intriguingly, to illustrate excerpts from Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, The Scribe makes use of scenes from little-seen drama Saving Lincoln (Salvador Litvak, 2013), whose central gimmick involves actors being green-screened in front of vintage civil-war photographs. In the context of a documentary mostly consisting of talking heads and archival and stock footage, the strangeness of seeing these transplanted scenes from another film risks swamping the power of Lincoln’s words. Yet it does inevitably remind the viewer of the extent to which Lincoln has been lionised by American popular culture, and how words can be reinterpreted in myriad ways and for different purposes. That’s a truth Freudenberg knows only too well – he openly borrows phrases and rhetorical techniques from Lincoln, William Shakespeare et al. in his speeches. It’s also reinforced by Tom Amandes’ performance in Saving Lincoln’s title role, which refocuses attention to the language.

And what language. Lincoln’s speech has, by Freudenberg’s own admission, become the ultimate cliché, yet the latter’s passion for the address cuts through all that. Reflecting on the speech, which comprises a grand total of 272 words, Freudenberg observes that it’s ‘really the distillation of all the great speeches of Lincoln, which were not high rhetoric but fierce, rigorous logic from his mighty mind’.

In a further example of Freudenberg’s appreciation of both humour and history, he and former NSW premier Neville Wran, with whom he worked for a decade, used ‘Gettysburg’ as shorthand to describe any inspirational speech on grand themes. They also coined the term ‘Chatham’ to describe the kind of speech that’s less concerned with grand ideas and more with pandering and vote solicitation. As the film reveals, the latter was named in honour of a town where then–British prime minister Harold Wilson was heckled. Wilson, politicking in the dockyard town of Chatham, was expounding on the benefits of the British navy when he asked the audience, rhetorically, ‘And why am I saying all this?’ Before he could continue, a member of the crowd yelled out, ‘Because you’re in Chatham!’[2]See Michael White, ‘A Brief History of Heckling’, The Guardian, 28 April 2006, <https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2006/apr/28/past.labour>, accessed 13 February 2019. Ultimately, Freudenberg notes that most speeches are a mixture of the two categories, a reflection of the messy reality of politics – flitting between high and low, lofty and direct, aspirational and transactional.

It’s in these moments that The Scribe transitions from straight biography to a more interesting rumination on language in politics. For one, its subject is not judgemental about the ostensibly less savoury aspects of the system (deal-making, for example), remaining a passionate advocate for democracy. ‘I think the most majestic thing that ever happens in Australia happens every polling day,’ Freudenberg remarks at one point, his observation accompanied by footage of politicians visiting schools and knocking on doors, and of ballot papers being collected. ‘The getting of votes is the essence of democratic politics. This is nothing to be apologetic about. When it’s all said and done, it does come down to persuading people to vote your way.’

*

Writing is often seen as a solitary profession, but Freudenberg says that, throughout his career as a speechwriter, he was ‘never alone’. For one thing, there were the great orators who inspired him, offering him a ‘mind or cultural companionship’. Then there were the more concrete relationships he had with ALP politicians.

‘I think we were a bloody good combination,’ Hawke observes – and, indeed, The Scribe spends a good deal of its running time documenting Freudenberg’s relationships with both Hawke and former prime minister Gough Whitlam. The speechwriter’s tie with the latter was particularly close: ‘It’s a process of osmosis, not deliberate study or imitation,’ Freudenberg reflects in the film. ‘I did get into his head, as he got into mine.’

After citing Whitlam’s 1972 ‘It’s Time’ oration as one of his key early-career highlights, Freudenberg says that there was something uniquely Australian about these so-called Policy Speeches (‘capital “P”, capital “S”’, he notes). According to him, no other democracy in the world had ‘this contract, a mixture of high endeavour and pork barrelling’. It’s not hard to see why Whitlam had the impact he did. Archival footage shows him proclaiming to a rapt audience, including a young Hawke in the front row, that ‘there are moments in history when the whole fate and future of nations can be decided by a single decision. For Australia, this is such a time.’ As the audience applauds enthusiastically, Whitlam struggles to conceal a smile. The energy is palpable.

So, in Freudenberg/Wran parlance, that’s a Gettysburg. But what about a Chatham? Freudenberg points out that, at the time of Whitlam’s speech, many of the suburbs in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane were un-sewered. So his speech-making would veer from grand proclamations that ‘it’s time’ right through to quotidian promises to fix suburban sewerage systems. He admits that ‘Whitlam was pilloried for it.’ Still, he had the last laugh. His shrewd interweaving of the mundane and very real with the lofty and abstract clearly resonated with voters: as Freudenberg asks the viewer with a sparkle in his eye, ‘Which was more interesting to people?’

Yet, of all the Freudenberg speeches featured in it, The Scribe spends most of its time on Hawke’s oration on the seventy-fifth anniversary of the landing at Gallipoli. Watching the speech now, you get a sense of the seriousness with which Hawke treated the occasion. Writing from a twenty-first-century perspective, academic Marilyn Lake has argued that there has been a marked shift in Australia’s relationship with Anzac Day:

New narratives about our troops fighting for ‘freedom and democracy’ and ‘a nation forged in battle’ began to be promoted by federal government departments.

Anzac Day thus appropriated an imperial war and re-cast it as a story of national independence to be taught to new generations of school children.[3]Marilyn Lake, ‘Beyond Anzac: What Really Shaped Our Nation?’, Pursuit, 23 April 2018, <https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/beyond-anzac-what-really-shaped-our-nation>, accessed 21 February 2019.

By choosing to focus on this speech, Cullen presents a powerful example of speechwriting’s ability to influence our national sense of ourselves. That this is also noticeably different from the contemporary idea of Anzac Day suggests that this power is impermanent.

‘None of us come here to glorify war,’a visibly emotional Hawke begins, in the archival footage presented.

For us, no place on Earth more grimly symbolises the waste and the futility of war, this scene of carnage in a campaign which failed. It is not in the waste of war that Australians find the meaning of Gallipoli, then or now.

‘That was a remarkable speech,’ Hawke reminisces, citing the occasion as the most moving experience he had as prime minister – a statement that’s clearly reinforced by his emotional delivery in the archival footage shown. In a telling moment of bathos, Cullen cuts from this footage to Freudenberg reading the script for the speech. His reaction? ‘Yeah, it’s not bad.’ He then attributes its power to the fact that he borrowed heavily from Shakespeare, before eventually conceding that it was the ‘nearest [he] could come – like, a thousand miles away – from Gettysburg’.

*

If there’s a spectre haunting The Scribe’s celebration of political rhetoric, it’s the election of Donald Trump. The incumbent US president intermittently makes his way into the film via campaign-rally footage, which is intercut with other examples of politicking. But it’s not until the end of the film that Freudenberg directly addresses the growing popular disenchantment with establishment politics. He often worries that speechwriting has helped ‘[diminish] the spontaneity of things’ in politics; then, enter Trump, who ‘cuts through all that’. While competing presidential candidate Hillary Clinton could give a ‘very good speech’, Freudenberg reflects that her flaw was not appearing as authentic as Trump’s ‘brawling, undisciplined, sometimes almost illiterate form of speeches’.

It’s in these fleeting moments that The Scribe becomes a more interesting exploration of the role rhetoric plays in politics. At times, interviewees gesture towards more complicated reflections – Carr, for example, notes that Freudenberg’s writing enhanced Calwell’s leadership so dramatically that it turned him into a ‘figure of more authority and of some style, more than he was really entitled to be’.

Towards the end of the film, Freudenberg argues that speechwriters for ex-president George W Bush may have done active harm to the global political order. Referring to Bush’s State of the Union address that popularised the concept of an ‘axis of evil’, he asserts:

That was put in by speechwriters simply because they thought it sounded good and had echoes of the war against [Adolf] Hitler and [Benito] Mussolini. And, of course, referring to Iran in particular as part of an ‘axis of evil’ has distorted US relations with Iran ever since, perhaps irreparably.

This is a case where the satisfaction that one gets from writing a stirring phrase can be damaging.

It’s a moment that highlights the lasting impact that rhetorical manipulation can have on the real world. But brief clips of Trump and Adolf Hitler aside, for the most part, The Scribe is a laudatory profile of its subject. That comes at the expense of a fuller – and, given our current political state, badly needed – consideration of rhetoric’s role in politics, and how that might be changing. It does, however, lead to some interesting reflections from a man who’s used to sticking his words in other people’s mouths.

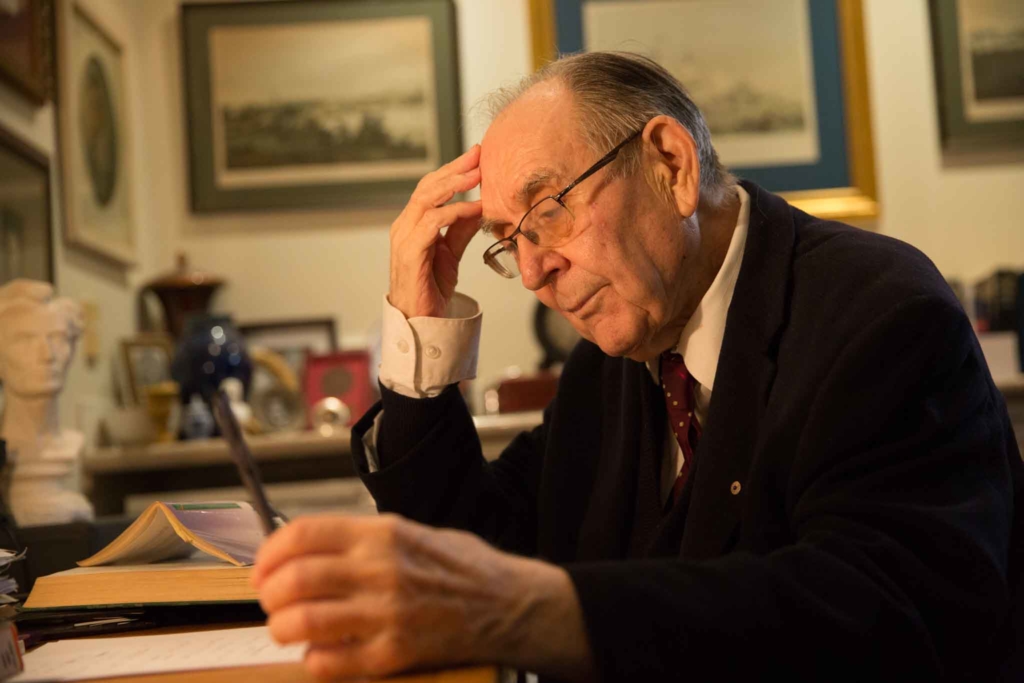

In The Scribe’s conclusion, the director herself – in the form of her off-screen voice – enters the film, asking Freudenberg whether he’s looking forward to his upcoming Whitlam Oration. The renowned speechwriter will be reading his own work aloud for a change. ‘No, I’m dreading it,’ he abruptly responds, cigarette in hand. He pauses, then softens slightly. ‘Because I don’t know what the hell I’m going to say.’ The feeling is not, Freudenberg clarifies, unique to this speech. Indeed, he approaches ‘every speech with a feeling of dread’, as if ‘this speech will be the one that I can’t do’.

Now in his eighties, Freudenberg reflects with wry amusement that age has turned him into the ‘last surviving expert on the past’, at least as far as the ALP is concerned. Certainly, his great collaborators have progressively passed into history. The ‘chameleon’, as Hawke called him, has run out of camouflage, and he can no longer wrap the rhetoric of history – from Shakespeare to Lincoln – around the political personalities of the present. ‘This time,’ he says of that pre-speech dread, ‘it’s even worse. I’m on my own.’

Endnotes

| 1 | Laurie Oakes, ‘Politicians Have Lost the Art of Making Great Speeches Thanks to Sound Bites’, The Herald Sun, 3 June 2017, <https://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/opinion/laurie-oakes/politicians-have-lost-the-art-of-making-great-speeches-thanks-to-sound-bites/news-story/ab733b3d583797b4e19124e227e6d8cb>, accessed 13 February 2019. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Michael White, ‘A Brief History of Heckling’, The Guardian, 28 April 2006, <https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2006/apr/28/past.labour>, accessed 13 February 2019. |

| 3 | Marilyn Lake, ‘Beyond Anzac: What Really Shaped Our Nation?’, Pursuit, 23 April 2018, <https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/beyond-anzac-what-really-shaped-our-nation>, accessed 21 February 2019. |