The trope of the failed passion project following a big success is a familiar satirical tool: passing from the stuff of insider Hollywood gossip to the common lexicon, its comic qualities have been played out through scenarios in hugely successful and influential cultural institutions like The Simpsons, Entourage and Apatovian comedies. It has become a narrative; a story we tell about misguided, quixotic quests or artistic hubris; a warning against unchecked ambition; a timely reminder of the cold reality of the box office.

George Miller’s tenth feature film, Three Thousand Years of Longing (2022), could be seen as an example of the trope. It’s a visual effects–heavy US$60 million fairytale that the 77-year-old Australian filmmaker spent over twenty years bringing to screen – finally having the clout to do so after the global commercial and critical success of Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) – only to end up a resounding box-office failure on release.[1]See Darren Mooney, ‘What Happened to Three Thousand Years of Longing?’, The Escapist, 2 September 2022, <https://www.escapistmagazine.com/what-happened-to-three-thousand-years-of-longing-box-office-failure-marketing-mgm/>, accessed 6 September 2022. But it’s hard to reduce this kooky, cockeyed, sprawling, visually audacious movie to a single trope when it is, itself, an examination of tropes.

A work of nesting narratives, Three Thousand Years of Longing finds a mystical, millennia-old djinn (Idris Elba) telling a host of tall tales to Alithea (Tilda Swinton), a contemporary scholar of narratology and thus an expert in the way stories have been told across time. As with all narrators, we’re invited to question his reliability, especially given djinns of fables are often tricksters. As the Djinn spins these yarns, they become a shared communion between himself and Alithea; his stories intersect with her life, her story. Eventually, it all becomes Alithea’s own tale to tell, which she writes in a book-within-the-movie (the book shares the movie’s title, which is another cinema trope deserving of mockery).

As the Djinn spins these yarns, they become a shared communion between himself and Alithea; his stories intersect with her life, her story. Eventually, it all becomes Alithea’s own tale to tell.

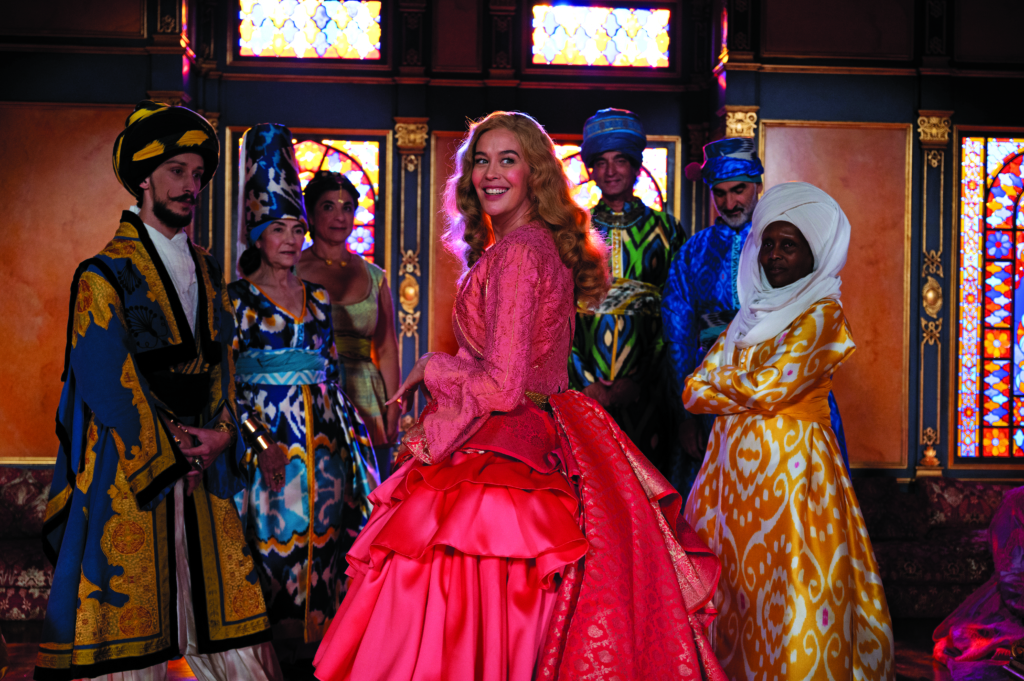

Miller has adapted the film from AS Byatt’s 1994 short-story collection The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye. ‘It’s a story that seemed to probe many of the mysteries and paradoxes of life,’ the director says. ‘It felt unique, something that you couldn’t quite fit into any genre […] There are stories within stories, a little like One Thousand and One Nights.’[2]George Miller, quoted in FilmNation Entertainment, Three Thousand Years of Longing press kit, 2022, p. 2. Three Thousand Years of Longing is, accordingly, a riff on the familiar set-up of the genie trapped inside a vessel who, upon release, offers three wishes in exchange for his freedom. It is steeped in the sensibilities of One Thousand and One Nights and taps into mythology and folklore, specifically the stereotypical imagery associated with the Ottoman Empire and the Islamic Golden Age (re-created on studio sound stages and digital backlots in COVID-era Sydney).

The film features three discrete stories – ‘A Djinn’s Oblivion’, ‘Two Brothers and a Gigantress’ and ‘The Consequence of Zefir’ – in which the Djinn’s romantic experiences through the colourful centuries are turned into something resembling fables. Spanning its titular timeframe, Miller’s movie is a portrait of how stories have survived across the ages, and of how human history – and human evolution – is indivisible from storytelling. ‘We’re creatures of story, we’re hardwired for story. That’s how we make sense of the world,’ suggests Miller.[3]George Miller, quoted in Xan Brooks, ‘“We’re Hardwired for Stories”: Mad Max Director George Miller on Myths, Medicine and a Pointy-eared Idris Elba’, The Guardian, 18 August 2022, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2022/aug/18/mad-max-director-george-miller-interview-idris-elba>, accessed 29 August 2022. Swinton offers a similar view: ‘Somebody said to me once that homosapiens [sic] should rather be more homo-narrans. That the storytelling ape is really what we are, more than wise; or rather, maybe the wisdom comes from being storytellers.’[4]Tilda Swinton, quoted in Three Thousand Years of Longing press kit, op. cit., p. 4.

As mentioned several times by characters in Three Thousand Years of Longing, every story about granted wishes is a cautionary tale. This movie, like so many fairytales before it, teaches the same essential lesson: ‘Be careful what you wish for.’

That experience of being told a story connects us back to formative childhood instances: the contemporary experience of being read to at bedtime; or the historical human trait of teaching children through fables. As mentioned several times by characters in Three Thousand Years of Longing, every story about granted wishes is a cautionary tale. This movie, like so many fairytales before it, teaches the same essential lesson: ‘Be careful what you wish for.’

The film opens with Alithea narrating the story – ‘Once upon a time …’ – in the modern moment, setting it, initially, in a time of global networks, pandemics and travel. She renders this moment as if strange, the powers of a handheld device a kind of modern myth: contemporary sorcery. At first, her narration speaks as if outside herself, outside of time, placing it not in this moment but in the great flow of human storytelling. ‘What else could we do but tell stories?’ Alithea asks, rhetorically. ‘Stories were the only way to make our bewildering existence coherent.’

She’s a British lecturer who’s arrived in Istanbul to deliver a talk on, yes, storytelling and myth. Browsing at a bazaar, she chooses an old bottle, and, when cleaning it back in her hotel room, soon – ‘contrary to reason’ – unleashes a giant, swirling genie, or djinn, who will grant her three wishes (unless she asks for endless wishes or eternal life). But Alithea, well schooled in cautionary tales, declines, fearing things going awry. Instead, she asks the Djinn to tell his story, in the hope of learning from the wishes and perils that have come before. ‘You and I are the authors of this story, and we can avoid traps,’ the Djinn says.

So, as he tells the tale of the ill-fated scenarios that led to his various incarcerations in the bottle that holds him, there’s an ongoing back and forth, discussion and commentary on the narratives within. Alithea becomes a part of this telling, even if she doesn’t want to be; ‘I’m not able to write myself out of it,’ she recognises. Through these told stories, there are constant evocations of the act itself, not to mention tales built around it.

During ‘Two Brothers and a Gigantress’, a queen (Zerrin Tekindor) hopes to distract her son, Murad IV (Oğulcan Arman Uslu), from assassination plots by parading ‘the greatest storytellers in the land’ in front of him. Most he drives away with ‘Off with his head!’–style fervour, only to eventually fall wholly in thrall to an old storyteller (George Shevtsov) who entrances him with his oration. And as Alithea hears the Djinn’s tales of ill-gotten wishes, tragic loves – including romances with the Queen of Sheba (Aamito Lagum) in fantastical antiquity and with Zefir (Burcu Göldegar) in the nineteenth century – and centuries-long imprisonments, she in turn inevitably falls under the Djinn’s spell, growing to love him through the emotional content and lyrical delivery of his stories. ‘Stories are like breathing to [djinns]; they make meaning,’ Alithea narrates. ‘Each story we tell is a fragment in a shapeshifting mosaic.’ To Miller, the Djinn ‘represents living storytelling, and also the effect of stories and how they can impact on the person who receives them’.[5]George Miller, quoted in Joe Utichi, ‘George Miller Says Overwhelming Amount of “Content” Charges Filmmakers to Deliver Truly Unique Stories – Cannes Studio’, Deadline, 26 May 2022, <https://deadline.com/video/george-miller-three-thousand-years-of-longing-interview-cannes/>, accessed 29 August 2022.

In Three Thousand Years of Longing, these stories’ impact on Alithea is profound. Yearning to feel the passion that she’s heard recounted, she finally makes her first wish: ‘I wish for you to love me in return.’ This draws the Djinn wholly into the real world, into her implausibly large and fancy townhouse back in London (a place of high technology and jarringly racist, pro-Brexit neighbours). Through their shared stories and shared feelings, each of them has become more emotional, more vulnerable, ultimately more human. Their shared tale becomes one of the most familiar sort – a love story – etched with the undeniable tragedy of a love that can never really be, one between an immortal being and an all-too-mortal human.

At first, the Djinn is enamoured of modern London – he calls human technological progress ‘quite a story’ – but his electromagnetic make-up is disrupted by the ‘ingenious devices all murmuring at once’ as the city’s digital signals flow through him. He’s weakened and suffering in Alithea’s world, so she casts her second wish: that he can return to his native spirit realm, returning intermittently to visit her.

It’s another bittersweet story of love thwarted by fate, one that Alithea recounts in an illustrated tome called Three Thousand Years of Longing. The book was created in real life by filmmaker Guillermo del Toro, who assumedly penned its drawings faster than Alithea would’ve written it (given she’s shown one-finger typing when at work in the film!) The book is, of course, as she describes it, ‘filled with stories’, serving as totem for the whole movie that shares its name.

Beyond its endless evocations of storytelling, the film – in its nineteenth-century tale of knowledge-seeking as well as its twenty-first century discourse about the place of the mystical in the quantified online times – is, as screenwriter Augusta Gore puts it, a ‘conversation about the interplay between science and myth, between technology and magic, between the ideas of immortality and what it means to live a mortal life with love and desire and fear’.[6]Augusta Gore, quoted in ‘George Miller Tells Us How He Made Idris Elba Even Bigger While Tilda Swinton Was Happy to Feel Small’, IndieWire, 23 May 2022, <https://www.indiewire.com/2022/05/george-miller-interview-idris-elba-tilda-swinton-three-thousand-years-of-longing-1234727324/>, accessed 29 August 2022.

It’s quite a change of pace for Miller, nestled in between two films in his ongoing Mad Max series: the aforementioned Fury Road and the upcoming Furiosa, due out in 2024. After shooting Fury Road ‘in the Namibian desert with one thousand people […] with real vehicles and speed’, as producer Doug Mitchell recounts,[7]Doug Mitchell, quoted in Three Thousand Years of Longing press kit, op. cit., p. 5. making a more contained, studio-based film was a gear shift. ‘Fury Road had little dialogue; in this film a large part of the action happens through the discourse between Alithea and the Djinn,’ Miller observes. ‘Fury Road played out in a compressed time frame – three days and two nights. This story happens over three thousand years.’[8]Miller, quoted in ibid., p. 5.

Taking in that time span allows the filmmaker to look at changes in not just human societies but storytelling itself; the further back in the past the narrative is set, the more folkloric and mythical it becomes. In the time of the Queen of Sheba, there are high-fantasy creatures, like an anthropomorphic giraffe with zebra stripes that sits in on a royal council. In the modern day, in contrast, the narrative is more self-aware, self-referential, a kind of metatextual commentary.

Miller is himself a storyteller – his career narrative of the ‘doctor turned director’ is itself a well-worn yarn[9]See Elizabeth Shockman & Julia Lowrie Henderson, ‘The Director of Mad Max: Fury Road Was a Doctor Before He Started Making Movies’, The World, 9 February 2016, <https://theworld.org/stories/2016-02-09/director-mad-max-fury-road-was-doctor-he-started-making-movies>, accessed 29 August 2022. – and sees cinema as a continuity of this great human tradition. Thus, the Mad Max series is in the lineage of lone-warrior legends (‘In Japan, they saw it as a samurai film. The French called it a western on wheels. In Scandinavia, it was a Viking movie’[10]Miller, quoted in Brooks, op. cit.); Babe (Chris Noonan, 1995) is a classic hero’s journey;[11]Brooks, ibid. and Marvel movies are ‘the vestiges of the Greek and Norse and Roman mythologies’.[12]George Miller, quoted in Mia Galuppo, ‘Three Thousand Years of Longing Star Tilda Swinton on Feature Films: “That Is My Flag, and I Fly It”’, The Hollywood Reporter,21 May 2022, <https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/three-thousand-years-of-longing-tilda-swinton-idris-elba-cannes-1235151692/>, accessed 29 August 2022.

‘When we go into the cinema, it’s a kind of public dreaming,’ the director says. ‘You are invited into the story, and hopefully caught up in it. Sharing dreams with strangers, on the big screen.’[13]Miller, quoted in Brooks, op. cit., p. 7. And Three Thousand Years of Longing is a big-screen production, a widescreen work of grandiose and expensive digital world-building from a filmmaker who routinely gets laudatory adjectives like ‘genius’ or ‘visionary’ attached to his name.[14]See, for example, Dan Marcus, ‘Three Thousand Years of Longing Cast and Character Guide: Meet the Djinn and All Who Knew Him’, Collider, 27 August 2022, <https://collider.com/three-thousand-years-of-longing-cast-and-character-guide/>, accessed 29 August 2022. Yet for all its wild visuals, spun yarns and star-wattage performances, it’s hardly a triumph; in fact, it may not even be considered ‘good’ by many. Given its big-budget box-office bomb status and the contrasting success of Miller’s previous film, Three Thousand Years of Longing was almost instantly regarded as a misfire – an ambitious failure.[15]The film has received mixed or negative reviews from various outlets including The New York Times, The New Yorker, The A.V. Club and Time Out. See Manohla Dargis, ‘Three Thousand Years of Longing Review: Desire, Once upon a Time’, The New York Times, 25 August 2022, <https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/25/movies/three-thousand-years-of-longing-review.html>; Anthony Lane, ‘Three Thousand Years of Longing and the Perils of Unworldliness’, The New Yorker, 26 August 2022, <https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/09/05/three-thousand-years-of-longing-and-the-perils-of-unworldliness>; Leigh Monson, ‘Three Thousand Years of Longing Doesn’t Quite Fit into 108 Minutes of Storytelling’, The A.V. Club, 25 August 2022, <https://www.avclub.com/three-thousand-years-of-longing-review-george-miller-1849455186>; and Phil de Semlyen, ‘Three Thousand Years of Longing’, Time Out, 22 May 2022, <https://www.timeout.com/movies/three-thousand-years-of-longing-2022>, all accessed 29 August 2022.

Ultimately, the film about storytelling will be stuck with a critical and popular narrative of its own. Whether seen as grand romantic gesture, filmic folly or footnote in its director’s career, the adventure of Three Thousand Years of Longing will be a story to be recounted: another layer added to the layers, another tale to be told.

Endnotes

| 1 | See Darren Mooney, ‘What Happened to Three Thousand Years of Longing?’, The Escapist, 2 September 2022, <https://www.escapistmagazine.com/what-happened-to-three-thousand-years-of-longing-box-office-failure-marketing-mgm/>, accessed 6 September 2022. |

|---|---|

| 2 | George Miller, quoted in FilmNation Entertainment, Three Thousand Years of Longing press kit, 2022, p. 2. |

| 3 | George Miller, quoted in Xan Brooks, ‘“We’re Hardwired for Stories”: Mad Max Director George Miller on Myths, Medicine and a Pointy-eared Idris Elba’, The Guardian, 18 August 2022, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2022/aug/18/mad-max-director-george-miller-interview-idris-elba>, accessed 29 August 2022. |

| 4 | Tilda Swinton, quoted in Three Thousand Years of Longing press kit, op. cit., p. 4. |

| 5 | George Miller, quoted in Joe Utichi, ‘George Miller Says Overwhelming Amount of “Content” Charges Filmmakers to Deliver Truly Unique Stories – Cannes Studio’, Deadline, 26 May 2022, <https://deadline.com/video/george-miller-three-thousand-years-of-longing-interview-cannes/>, accessed 29 August 2022. |

| 6 | Augusta Gore, quoted in ‘George Miller Tells Us How He Made Idris Elba Even Bigger While Tilda Swinton Was Happy to Feel Small’, IndieWire, 23 May 2022, <https://www.indiewire.com/2022/05/george-miller-interview-idris-elba-tilda-swinton-three-thousand-years-of-longing-1234727324/>, accessed 29 August 2022. |

| 7 | Doug Mitchell, quoted in Three Thousand Years of Longing press kit, op. cit., p. 5. |

| 8 | Miller, quoted in ibid., p. 5. |

| 9 | See Elizabeth Shockman & Julia Lowrie Henderson, ‘The Director of Mad Max: Fury Road Was a Doctor Before He Started Making Movies’, The World, 9 February 2016, <https://theworld.org/stories/2016-02-09/director-mad-max-fury-road-was-doctor-he-started-making-movies>, accessed 29 August 2022. |

| 10 | Miller, quoted in Brooks, op. cit. |

| 11 | Brooks, ibid. |

| 12 | George Miller, quoted in Mia Galuppo, ‘Three Thousand Years of Longing Star Tilda Swinton on Feature Films: “That Is My Flag, and I Fly It”’, The Hollywood Reporter,21 May 2022, <https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/three-thousand-years-of-longing-tilda-swinton-idris-elba-cannes-1235151692/>, accessed 29 August 2022. |

| 13 | Miller, quoted in Brooks, op. cit., p. 7. |

| 14 | See, for example, Dan Marcus, ‘Three Thousand Years of Longing Cast and Character Guide: Meet the Djinn and All Who Knew Him’, Collider, 27 August 2022, <https://collider.com/three-thousand-years-of-longing-cast-and-character-guide/>, accessed 29 August 2022. |

| 15 | The film has received mixed or negative reviews from various outlets including The New York Times, The New Yorker, The A.V. Club and Time Out. See Manohla Dargis, ‘Three Thousand Years of Longing Review: Desire, Once upon a Time’, The New York Times, 25 August 2022, <https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/25/movies/three-thousand-years-of-longing-review.html>; Anthony Lane, ‘Three Thousand Years of Longing and the Perils of Unworldliness’, The New Yorker, 26 August 2022, <https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/09/05/three-thousand-years-of-longing-and-the-perils-of-unworldliness>; Leigh Monson, ‘Three Thousand Years of Longing Doesn’t Quite Fit into 108 Minutes of Storytelling’, The A.V. Club, 25 August 2022, <https://www.avclub.com/three-thousand-years-of-longing-review-george-miller-1849455186>; and Phil de Semlyen, ‘Three Thousand Years of Longing’, Time Out, 22 May 2022, <https://www.timeout.com/movies/three-thousand-years-of-longing-2022>, all accessed 29 August 2022. |