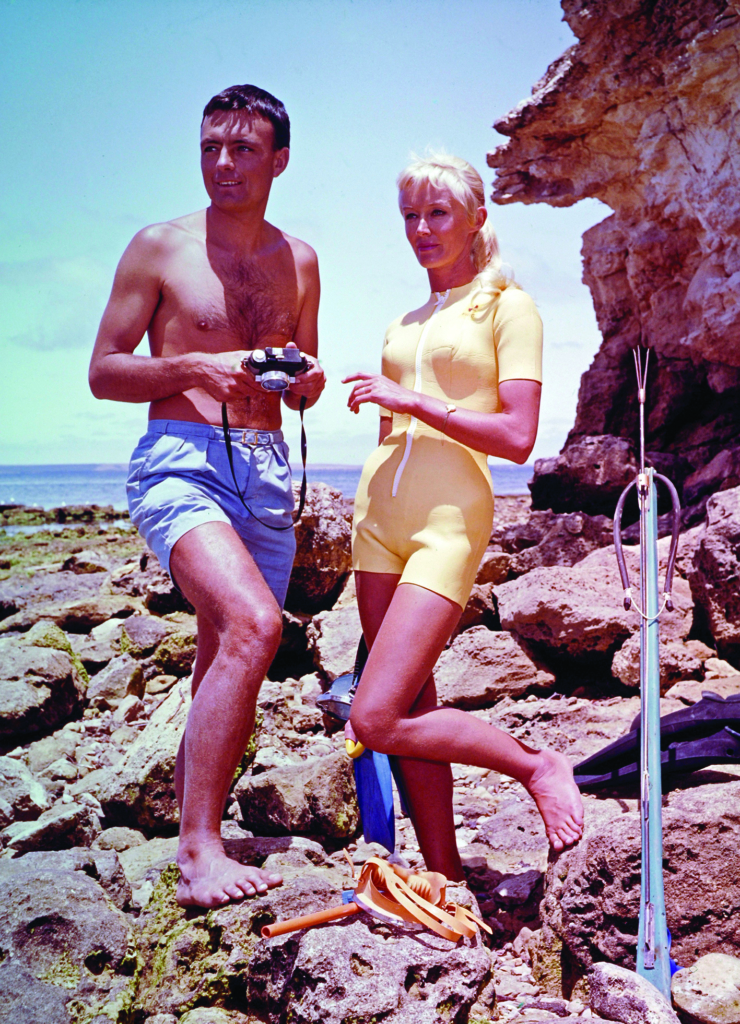

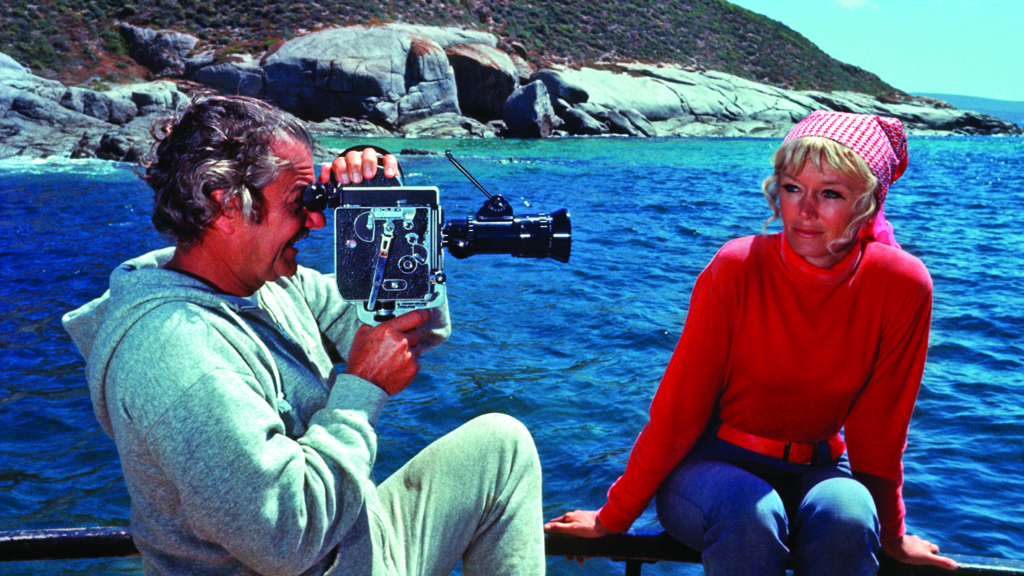

An exploration of one of Australia’s most fascinating yet overlooked screen figures, Playing with Sharks: The Valerie Taylor Story (Sally Aitken, 2021) sheds some overdue light on the titular underwater photographer and filmmaker. Premiering at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival,[1]Following its Australian and New Zealand theatrical release, the film has been slated to make its bow on streaming service Disney+ in late July 2021. Aitken’s documentary chronicles Taylor’s life and career from her early endeavours as a shark hunter and documentary maker[2]Valerie and Ron Taylor worked on over twenty documentaries together. The most iconic of these, Blue Water, White Death, brought them to the attention of director Steven Spielberg. They also subsequently shot underwater sequences for the films Orca (Michael Anderson, 1977), Jaws 2 (Jeannot Szwarc, 1978), The Blue Lagoon (Randal Kleiser, 1980), Gallipoli (Peter Weir, 1981) and Sky Pirates (Colin Eggleston, 1986), among others. to the iconic shark footage she shot for Hollywood blockbuster Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975), as well as her later work as a respected marine conservationist.

I talk to the director about finally giving the 85-year-old her due credit, and about her effort to redefine a living legend of oceanography.

Oliver Pfeiffer: Why did you feel compelled to bring Valerie Taylor’s life to audiences’ attention?

Sally Aitken: The story basically starts with the producer’s interest. Bettina Dalton, who’s this wildlife fanatic and history filmmaker, had known and worked with Valerie and [her husband] Ron Taylor. When she was a child, Valerie was like this Marvel hero for her. However, she noticed that Valerie didn’t even have a Wikipedia page. She said, ‘Here’s this woman who […] has created such a legacy in conservation; how has she not even got a Wikipedia page?’ When I was approached, I didn’t know very much about the story […] But here’s this absolutely one-of-a-kind, phenomenal woman who has a kind of boys’ own adventure tale of a life that is worth celebrating. And the fact that there was this enormous film library to draw on, and these very significant cultural touchstones, like Jaws – well, the whole thing was irresistible.

Before your documentary, it did feel like Taylor was an underexplored Aussie personality …

The truth is she was incredibly well known, particularly in Australia during the seventies and eighties, but there are generations now that have never heard of her. Certainly, the reaction [to the documentary], particularly internationally, is that she is a Hidden Figures [Theodore Melfi, 2016] kind of character. As a storyteller, what an incredible privilege, responsibility and delight [it is for me] to be illuminating a life that is otherwise unknown.

Being a young woman in the male-oriented environment of deep-sea divers was a rarity during the 1960s when she started out. Did you feel compelled, particularly when gender equality is very much an issue now, to explore the story’s feminist qualities too?

Of course I was activated and excited by the fact that she is this incredible example of a strong female character. She would be the first to say that there weren’t many other women […] but the fact that she delighted in taking it to the guys is part of her character. It isn’t in the film, but she was invited to the [St George] Spearfishing Club [after she] and her brother went spearfishing and had this massive haul. There was somebody [there] who looked at her catch and said, ‘Would you like to come and join our club? We’re very short of women, and you seem to be rather good!’ She delights in that sort of extraordinariness, but it doesn’t diminish the fact that she was incredibly good and she had to be stronger, better and sharper than the guys.

‘I was activated and excited by the fact that Valerie is this incredible example of a strong female character … The fact that she delighted in taking it to the guys is part of her character.’

– Sally Aitken

Speaking of the contemporary gender lens, you want to celebrate this because women continue throughout history to have achieved amazing things. Whether we tell their stories or not is a different matter. The weight of telling stories and then retelling those stories, that’s what gives people legendary status; so, as a woman, it’s inescapable.

From a research perspective, it must have been a mammoth undertaking, considering all the oceanographic footage that the Taylors had recorded. How did you approach this?

With absolute delight and trepidation! It’s amazing that we had this depth of [archival material], so I just said, ‘Let me dive in!’ It was no small undertaking. The reality is the film library alone is one thing, but I also had access to Valerie’s diaries from the 1960s that she has kept every year since. So I started with the diaries because they were firsthand accounts and weren’t a retrospective thing. It wasn’t like interviewing her today and saying, ‘Take me back to that time.’ I was reading all that on the page – how she was responding, what she was thinking, how she was feeling – and, for a while, I felt somehow the diaries would be part of the film. But the fact that we had this incredibly vibrant, beautiful, wise older woman [as] a very active participant in her own story sort of trumped that need, I suppose.

With the footage, I think it was in the region of 5000 hours. It’s not only the rushes that Ron and Valerie shot, but all the mini projects they were involved in. Then, of course, 60 Minutes would do a piece about illegal clam poaching, and there they are; and then a story on shark nets taken down, and there they are […] So I did watch everything. The archive had aesthetic qualities, literary storytelling qualities, and then this kind of metaphoric application as well. I was constantly revisiting it with my editor.

You don’t shy away from how conflicted Valerie became over her and her husband Ron’s involvement in Jaws – given that the film ended up giving sharks such a bad name – or from acknowledging her early shark hunting.

I think it’s one of the things that I really respect about her. Valerie started as a hunter, and she’s never made an apology for that. I really admire that because it’s [through] that grand arc and potential for transformation […] that you do feel very inspired and think, ‘Gosh, somebody can essentially be a lethally good slayer of wildlife, and yet go the full range to not just appreciating and understanding but to advocating for [their welfare].’ Having said that, the idea of seeing herself wielding a spear gun in full frame with accuracy […] – no, of course she hates it, and she was distressed that I wanted to include it. Yet she knows the power of a story is really important, and the power of actually [representing] her own truth. So I really admire that: someone who is honest about themselves.

And then, with Jaws,she was very careful to be accurate. For [her and Ron], it was an amazing opportunity and access to Hollywood. It was the culmination of the huge knowledge that [they] had acquired through personally [putting in the] hard yards. The reason they were approached was because they were experts – because Spielberg and his team knew they were the shark experts – and she says the experience of making Jaws was brilliant […] But the aftermath[3]Shark researcher George Burgess estimates that ‘the number of large sharks fell by 50% along the eastern seaboard of North America in the years following the release of Jaws’. Mary Colwell, ‘How Jaws Misrepresented the Great White’, BBC News, 9 June 2015, <https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-33049099>, accessed 10 May 2021. was truly surprising for everybody.

‘Nothing in Valerie’s life happens because she intellectualises it … She has great honour in the idea that, through personal experience and personal action, you can say things with authority.’

– Sally Aitken

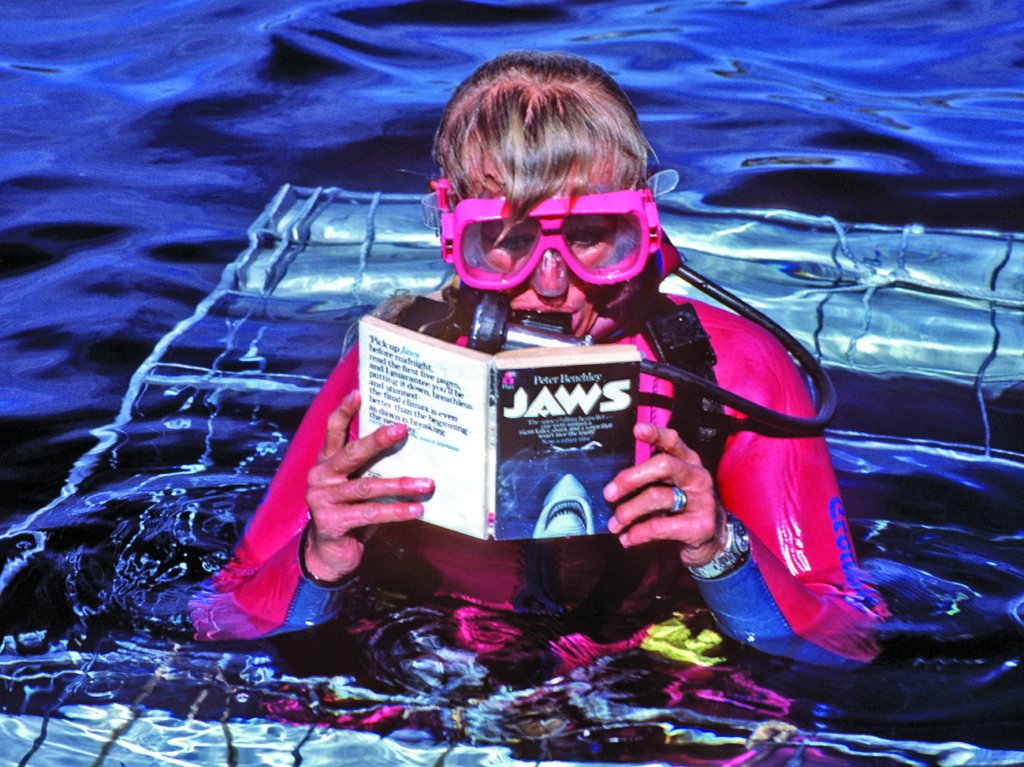

She’s not someone who wallows in emotion, because she’s a doer and really Australian like that. So, for her, wallowing in a kind of guilt and regret isn’t going to do anything for the sharks. If anything, it was a galvanising moment for her to make people aware of the real great whites that she and Ron and many of her contemporaries knew about. Again, nothing in Valerie’s life happens because she intellectualises it. That’s not to say she’s not a smart person – quite the contrary, she’s hugely intelligent – but she has great honour in the idea that, through personal experience and personal action, you can say things with authority. She knew it was incumbent on her to make others aware of the fact that Jaws was fictitious. She’s very precise with her words: it’s not a shark attack; it’s a shark bite. These things were born out of the pain of realising that people didn’t have the same understanding, but also that galvanising requirement to not chastise [them] for what they didn’t know.

Playing with Sharks doesn’t feature interviews from any other talents involved with Jaws. Did you reach out to Spielberg?

Of course we wanted Steven Spielberg to talk about the film – no one would dispute that Jaws is one of the [masterpieces] of cinema and that it terrified [people]. The fear was there, but the fascination was there too. So, I think it is equally true that Jaws excited a whole generation of marine scientists to become marine scientists. Spielberg was up for doing the interview, but it was a situation of logistics. However, the person I really would’ve loved to interview was [director] James Cameron, because [he] actually approached Valerie a few years ago to say Blue Water, White Death [Peter Gimbel & James Lipscomb, 1971][4]The documentary marked the first time that an expedition set out to film great white sharks. It’s notable for showing the Taylors swimming cageless among a school of these sharks. literally changed his life. He was a very disaffected teenager who didn’t know what he wanted to do. He walked into a cinema, saw [the film], and it made him realise he wanted to become an underwater explorer. I thought, ‘Wow, talk about an influencer.’

If one was calculating about it, you could say it would be great to have those big names in there. However, I think, personally, Valerie’s story stands [for] itself, and is perhaps more remarkable. Not because we didn’t want to include those characters, but because, in the scale of Valerie’s life, they are small pieces.

Were there any aspects to her life or career that were off limits?

She was candid and deeply respectful of a director’s process. There were many things I’m sure she would’ve loved to have had included in the film, because she is an incredibly accomplished artist. She also has a long and enduring relationship with many other marine animals […] But no, she didn’t ever say you couldn’t talk about this or that. Personally, I find her discussion around Ron’s death[5]Ron Taylor died from leukaemia in 2012 at the age of seventy-eight. incredibly poignant because it is not verbose and expressive, but the idea that she goes to bed with the pillow tells you everything.

Playing with Sharks also touches on the ramifications of old age. I’m thinking about the moment when you witness the painful struggle of the now-elderly Valerie putting on her pink wetsuit to go deep-sea diving again …

Yes, and of course, as a person, you’re there and you’re filming that. You feel awful. But I’m not making her do it – she wants to go diving […] The scenes in Fiji were actually the first things we filmed due to it being more comfortable to dive at that particular time of year, and also because of the shark population [there].

One of the things that happened was I had found the archival imagery of the 1960s in Fiji, and I remember looking at a frame of Valerie – very young, beautiful full expression in her eyes – on the boat heading out to the lagoon, and then seeing that very same frame in the footage we had taken that day. I sort of put them up against each other and thought, ‘There’s something in this intersection that is really interesting.’ I loved seeing her as an older woman because there’s something about the wisdom and the lived experience – when you place that against the younger self, she’s dynamic, she’s [oriented towards] action, she doesn’t know the life she’s going to have, but she’s really up for having it. You can never do that in real life, [but in] a film you can actually put those things together. It wasn’t so much a conscious thing of wanting to talk about the ravages of time; it was something very much expressed because of that ability to see time in a collapsed way.

Endnotes

| 1 | Following its Australian and New Zealand theatrical release, the film has been slated to make its bow on streaming service Disney+ in late July 2021. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Valerie and Ron Taylor worked on over twenty documentaries together. The most iconic of these, Blue Water, White Death, brought them to the attention of director Steven Spielberg. They also subsequently shot underwater sequences for the films Orca (Michael Anderson, 1977), Jaws 2 (Jeannot Szwarc, 1978), The Blue Lagoon (Randal Kleiser, 1980), Gallipoli (Peter Weir, 1981) and Sky Pirates (Colin Eggleston, 1986), among others. |

| 3 | Shark researcher George Burgess estimates that ‘the number of large sharks fell by 50% along the eastern seaboard of North America in the years following the release of Jaws’. Mary Colwell, ‘How Jaws Misrepresented the Great White’, BBC News, 9 June 2015, <https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-33049099>, accessed 10 May 2021. |

| 4 | The documentary marked the first time that an expedition set out to film great white sharks. It’s notable for showing the Taylors swimming cageless among a school of these sharks. |

| 5 | Ron Taylor died from leukaemia in 2012 at the age of seventy-eight. |