Ukraine Is Not a Brothel (2013) is a documentary that raises many more questions than it answers. It centres on the internationally notorious feminist activist group Femen, known for its topless protests against everything from environmental destruction and human trafficking, to the Belarusian KGB and pornography – and most recently for its open hostility to Islam. Director Kitty Green doesn’t shed any light on that last aspect, nor does she intend to; instead, she presents a series of vignettes that glimpse behind the curtain of an operation with highly visible soldiers but a much more complex and opaque leadership.

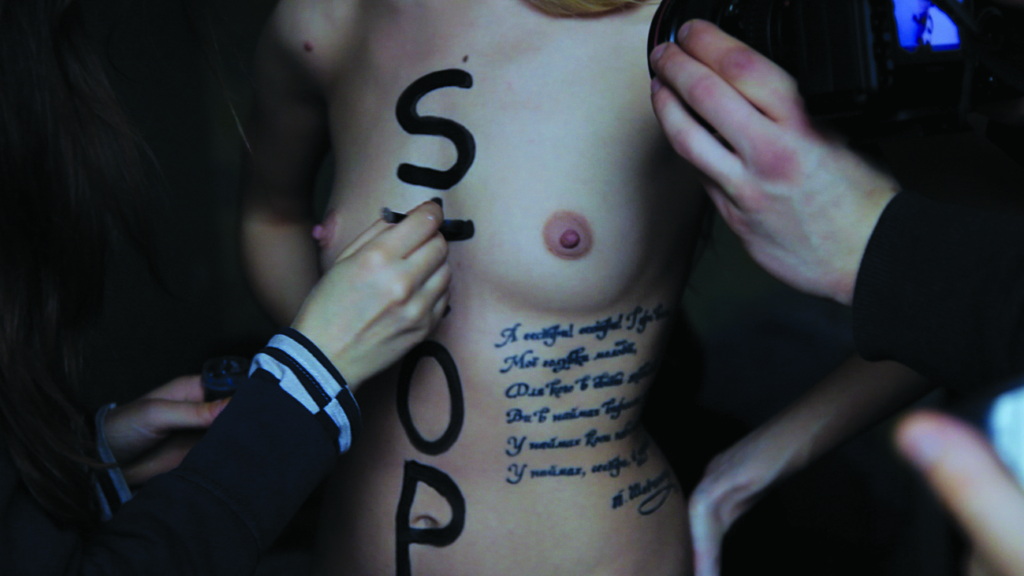

The documentary introduces us to the women who risk so much by executing these contentious actions, which are designed to draw attention to the political struggle of women in Ukraine and elsewhere. But these protests also have a very clear modus operandi: as the women are topless and write messages on their breasts, the media cannot resist covering their protests, which dramatically furthers Femen’s reach. In this way, these women are arguably reclaiming their bodies for their own political ends. Femen’s unofficial motto is:

Our God is a Woman!

Our Mission is Protest!

Our Weapon [sic] are bare breasts![1]‘About’, Femen website, <http://femen.org/about>, accessed 11 August 2014.

It can’t be said to have failed, given the global attention Femen has created for its ‘brand’ of beautiful women with bare breasts covered in punchy rhetoric, with garlands in their hair, and who loudly chant, among other slogans, ‘Ukraine is not a brothel!’ (referring to the incredibly high percentage of women trafficked, tricked and forced into the sex trade in this part of Europe – a criminal phenomenon that has affected Ukrainian women disproportionately[2]Natalia Antonova, ‘Welcome to Kiev: City of Beautiful Women and a Prospering Sex Industry’, The Guardian, 24 April 2012, <http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/apr/24/kiev-beautiful-women-sex-industry-ukrainian>, accessed 11 August 2014.).

An activist and member of Femen, Sasha, criticises other women in Ukraine, saying that Femen’s protests need to be shocking in order to reach them and pierce through their veil of apathy and lack of insight. Yet, at times, Femen’s members exhibit a startling dearth of consideration for ‘other women’. Throughout the interviews, there is a theme of violent contempt not only for sex work, but also for traffickers, pimps and, strangely, the women who are coerced into the sex trade. It may be difficult for Australian feminists, many of whom are fighting to destigmatise and legitimise sex work in our country, to empathise with the terror of trafficking that hangs over these women’s lived realities. But, perhaps due to her Australian-Ukrainian background, Green felt motivated to present the sharp contrast between Femen’s ‘interpretation’ of the feminist cause and ours. Certainly, this spectre is present throughout the film via the interviews with a number of women, almost all of whom are Femen members and active agents. These women seem to make no distinction between prostitution and sex work, and this is evident in their casual denigration of other women as victims of an industry that they themselves have escaped – partly because, instead, they have committed themselves to a feminist activist movement that uses their bodies in a slightly different way.

At one point, a Femen member laughs and says, ‘What is the difference between a feminist and a prostitute?’ – and it’s clear the joke is not particularly funny, even to her. This takes on a darker resonance as the film unfolds and refers subtly to the unseen leader, and founder, of the group. For viewers, the film’s climax isn’t so much discovering that he is a man (this information had been disseminated online many months ago) but rather the moment of meeting him and seeing his motivations and attitudes towards the women of Femen laid bare. It’s a chilling denouement, not only because Green has effectively built suspense around him but also because, by the time we do meet Femen’s puppetmaster, it has become clear the activists on the ground are largely scared of him, particularly when protests don’t go according to his extremely specific plans.

We come to understand that what the women of Femen share is a sense of despair about – and, in some cases, an acceptance of – the status quo and the few paths offered to them.

The film paints a bleak picture of life for – and the limited possibilities open to – the average young woman in Ukraine, which might also explain the risks that the women of Femen are willing to take in order to do something constructive and pointed with their bodies and their lives. Inna calls it

a chance to participate in something good. Not like other girls. I see the way other Ukrainian girls live, and I’m so grateful that I found Femen and that I didn’t end up in prostitution.

We come to understand that what the women of Femen share is a sense of despair about – and, in some cases, an acceptance of – the status quo and the few paths offered to them. It almost feels like brinkmanship born of anger and desperation, infused with pride at the genuine bravery and solidarity they demonstrate by executing these dangerous acts together. They see choosing Femen as forging a new path – and, in some ways, it is just that. They have this in common with their similarly famous sisters in Pussy Riot, whose incarceration seems every bit as possible for the activists of Femen, especially as the latter routinely experience physical and sexual abuse at the hands of the police, who regularly arrest and release them. A particularly harrowing account of a brush with the KGB drives home the similar dangers that Femen and Pussy Riot operate under – a repressive police state with aspirations to be taken seriously by the West. For these women, this sometimes means the authorities deal with ‘potentially embarrassing’ dissent at inopportune times in harsh ways, resulting in summary punishments that seem outlandish and terrifying to us.

There is no question that these stunts take courage, manifested physically and emotionally. And, like PETA, Femen is unafraid of crossing the lines of propriety or ‘sound judgement’. That the slogans painted on the women’s breasts are in English is telling – there is a strong vein of pro-Western sentiment and an uncritical acceptance of free-market values in Femen’s talk of the ‘brand’, performance and pay-off, and in their ‘reports’ to the ‘boss’. One woman agrees that ‘in order to promote the brand, Femen needs beautiful girls. It’s a marketing strategy.’ She then goes on to compare the success of the Femen brand with McDonald’s: it’s not good for you, but it’s popular nevertheless. Ukraine is full of these half-baked insights and fragments of bigger narratives relating to capital, culture and patriarchy as superstructures.

But what of Femen’s increasing focus on Islam and the oppression of women within it? Some of the most problematic Femen protests have targeted not only Islam itself but also Muslim women, who, in wearing the veil, are accused of accepting their oppression and supporting ‘the blood and all the crimes that are based on [their] religion’.[3]Femen France leader Inna Shevchenko, quoted in Uzma Kolsy, ‘Put Your Shirts Back on: Why Femen Is Wrong’, The Atlantic, 6 May 2013, <http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/05/put-your-shirts-back-on-why-femen-is-wrong/275582/>, accessed 11 August 2014. The arguably racist and certainly Islamophobic aspects of the Femen agenda are entirely absent from this film, which I found frustrating, even though I can appreciate that the director wants to tell a different story. Green clearly has a very close rapport, if not friendship, with these women, despite being invisible to the viewer, and the intimacy of her interactions with them allows for an incredible candour between documentarian and subject.

A refreshing and at times brutal honesty about men is a recurring theme of the conversations. Anna explains that, while the majority of financial donations come from men, this isn’t necessarily because men love the protests more than women do; it’s simply because men have all the money. Similarly, Oksana repeats the fragment ‘These men …’ before trailing off, and it’s hard to think of who exactly she’s referring to, if not everyone. It’s a world that, especially for these women, still revolves exclusively around men. And, in the documentary, we see that they are at times openly resentful and deeply suspicious of, and even hateful towards, the men of their world: police officers, photographers, lawyers, donors, journalists and, as the documentary reveals, even the man behind Femen itself. It’s almost as though men handle all the things that are mysterious and remote to these women – money, power, the law, their freedom, travel, protection, political rhetoric, prisons, the media. There is a sense that the women of Femen see ‘the order of things’ as perpetuated by men, and that they have no real conception of men being meaningful allies. Add this to the feeling that, to Femen, ‘other women’ have it all wrong, too, and I found myself asking: who are their protests actually for?

‘Nobody listens, but they look when we are beautiful and naked,’ says Oksana, in between bouts of nervous laughter and piercing glares, as though an appeal to men on their most base level is somehow the most promising and potentially effective bargaining chip. It’s a powerful moment and provides the subtext that permeates the film: if you must look at me, and demean me, objectify me and even harm me, at least listen to me. There’s no performance of fear; it is palpable. Many of these women exhibit textbook signs of living with and in abusive relationships – the hesitation to take ownership of their ideas and assert themselves, the explanation of how ‘he’ only behaves this way occasionally, the backtracking that comes with guessing that what you’ve described ‘doesn’t look good’ to your interlocutor. I don’t know exactly what Green was attempting to show me, but I saw considerable pain and damage, and, in at least one member of Femen, the first, tentative steps towards recovery.

After watching this film, I thought a lot about the nexus between patriarchy and capitalism, and how former Soviet countries (among others) problematically fetishise the free market as an antidote to the problems of their communist past. I thought of how this affects women in particular, and how women everywhere manage to find ways of banding together to reject the paltry patriarchal offerings they are insulted by. I thought of how Muslim feminists, sex-worker feminists, queer feminists, black feminists and trans feminists continue to struggle, with fearlessness and strength, and how these women, too, are working at the intersection of what they think is right and the best they can do in their difficult circumstances. For its female activists, Femen may be a vehicle for liberation, despite being created by a man who seems to have little regard for their abilities. Alternatively, the experience of it may simply arm them with the means to liberate themselves. My feminist heart hopes for the latter.

http://www.ukraineisnotabrothel.com

Endnotes

| 1 | ‘About’, Femen website, <http://femen.org/about>, accessed 11 August 2014. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Natalia Antonova, ‘Welcome to Kiev: City of Beautiful Women and a Prospering Sex Industry’, The Guardian, 24 April 2012, <http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/apr/24/kiev-beautiful-women-sex-industry-ukrainian>, accessed 11 August 2014. |

| 3 | Femen France leader Inna Shevchenko, quoted in Uzma Kolsy, ‘Put Your Shirts Back on: Why Femen Is Wrong’, The Atlantic, 6 May 2013, <http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/05/put-your-shirts-back-on-why-femen-is-wrong/275582/>, accessed 11 August 2014. |