Colin Thiele’s 1963 novella Storm Boy was meant for children first and foremost, and the same can be said about Henri Safran’s beloved 1976 film adaptation, scripted primarily by Sonia Borg. But the story told in both is part of the larger body of white Australia’s mythology. Unlike many such myths, this one concerns a hero at home in the landscape – specifically, the landscape of the Coorong, the long stretch of saltwater lagoons running parallel to the coastline in the eastern part of South Australia.

In a shack between the Coorong and the sea lives an eccentric beachcomber nicknamed Hide-Away Tom (played by character actor Peter Cummins in Safran’s film), who has retreated from civilisation following the death of his wife. But the real escape is accomplished by his young son, the titular Storm Boy (Greg Rowe), who roams wild and free and stays out in all weathers – not because he is neglected, but because, as Thiele explains, he can’t bear to be indoors:

He loved the whip of the wind too much, and the salty sting of the spray on his cheek like a slap across the face, and the endless hiss of the dying ripples at his feet.

For Storm Boy was a storm boy.[1]Colin Thiele, Storm Boy, 40th anniversary edn,New Holland Publishers, Sydney, 2002 [1963], Kindle ebook version.

Easily read in one sitting, Thiele’s novella is dense with lyrical detail but relatively short on dramatic incident. With no companions of his own age, Storm Boy befriends another solitary resident of the Coorong, an Aboriginal man known as Fingerbone Bill, who tutors him in the ways of nature (this character is played in the film by David Gulpilil – then in his early twenties, in contrast to the ‘wizened’ figure described in the book). An instinctive friend to the vulnerable, Storm Boy rescues a trio of pelican chicks dubbed ‘Mr Proud’, ‘Mr Ponder’ and ‘Mr Percival’; the last of these becomes his constant companion, and takes a central role in rescuing the victims of a shipwreck, with his master guiding him from the shore. Finally, and inevitably, the idyll must end: Mr Percival is shot and killed by hunters who represent the evil side of human nature, and Storm Boy is sent away to school, his childhood effectively over.

Safran’s Storm Boy is a film that several generations of Australian viewers are bound to look on with nostalgia – as a song of innocence, as a reminder of their own younger days and as a relic of an era when Australian cinema itself seemed less wedded to commercial formula. This last perception may be, in part, illusory: as critic Terry Hayes has identified, the film’s box-office success was the product of shrewd calculation on the part of its producer, Matt Carroll, who took on the task of distribution and enlisted Thiele – an educator as well as an author – to ensure the adaptation attained maximum exposure in Australian schools.[2]Terry Hayes, ‘Storm Boy’, Metro, no. 197, 2018, p. 104.

The idea of a slicker, more modern Storm Boy comes close to being a contradiction in terms. From today’s vantage point, the story seems unequivocally an artefact of a partly idealised past.

While Storm Boy and Mr Percival remain alive and well in the memories of many, their story has now been retold for a new generation by director Shawn Seet and screenwriter Justin Monjo. This big-screen remake comes as no great surprise in itself: over the past few years, many makers of film and TV have begun to view the glory days of modern Australian cinema, from the 1970s through to the mid 1990s, as territory worth revisiting and mining.[3]See Jake Wilson, ‘In Search of Australia, Then and Now’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 16 January 2018, <https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/movies/in-search-of-australia-then-and-now-20180116-h0izjs.html>, accessed 13 November, 2018. Yet the idea of a slicker, more modern Storm Boy comes close to being a contradiction in terms. From today’s vantage point, the story seems unequivocally an artefact of a partly idealised past – when children were willing to make their own entertainment out of doors and when dropouts could take a laissez-faire approach to parenting without fear of child-protection services swooping in.

Moreover, the romantic view of childhood and nature conveyed in both Thiele’s book and Safran’s film is harder to swallow whole than it used to be, especially since both push women to the sidelines while treating the adult Fingerbone with faint condescension as a sidekick to the young, white hero. One source for these plot elements appears to be Adventures of Huckleberry Finn – referenced explicitly in Thiele’s book, in which Storm Boy is described as wearing a ‘Tom Sawyer hat’.[4]Thiele, op. cit. But, rather than echoing Mark Twain’s complex ironies, Storm Boy relies on the conventions of children’s fiction to provide a reassuring answer to one of the central questions facing Australian cinema and Australian culture generally: in what sense can non-Indigenous Australians feel ‘at home’ in a land where their forebears arrived relatively recently, and where the scars of colonisation are far from healed?

There is evidence that Seet and Monjo had at least some of this in mind when mounting their remake: as they explain in the film’s press kit, they sought permission to shoot on the Coorong from the Ngarrindjeri people, the traditional custodians of the land, and consulted with them extensively on the script (particularly on the representation of Fingerbone, a Ngarrindjeri man in this telling of the story).[5]Sony Pictures, Storm Boy press kit, 2018, p. 6. Yet their Storm Boy is pointedly a period piece, shifting Storm Boy’s childhood back in time to the 1950s[6]The setting in Safran’s film was contemporised to the 1970s. and reproducing the essential moments of the story in a self-consciously reverent way. In some respects, indeed, their rendition feels more old-fashioned than Safran’s: it emphasises the fatherly anxieties of Tom, played here by the youthfully handsome Jai Courtney, and lessens the importance of Fingerbone, portrayed by Trevor Jamieson as a middle-aged, relatively self-effacing figure with none of the rebellious aura of Gulpilil (whose Fingerbone’s red jumper recalls the red jacket worn by James Dean’s Jim in Rebel Without a Cause, Nicholas Ray, 1955). Finn Little, in the title role, is likewise a more conventional presence than his 1976 counterpart – a practised child actor rather than a new discovery, whose Storm Boy appears less self-sufficient and more eager to please and be understood.

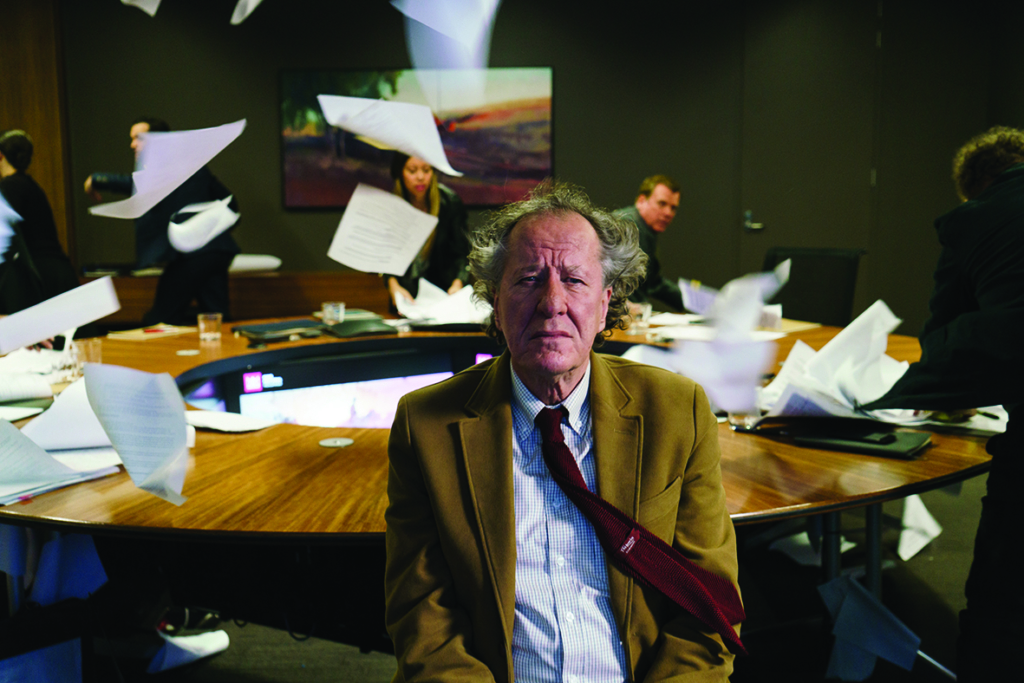

In effect, however, Seet’s Storm Boy is not a straight remake but an unofficial sequel to its famous forerunner: as in so many recent ‘reboots’, part of the subject is precisely the gap between the film we are watching and the earlier one that many adult viewers will have retained in memory. Thiele’s story has been enclosed within a newly devised frame, with the ageing former Storm Boy (Geoffrey Rush) – now known better by his real name, Michael Kingley – looking back on his childhood from the vantage point of the present. Somehow, in the interim, he’s become a highly successful businessman whose company – now run by his son-in-law, pointedly named Malcolm Downer (Erik Thomson) – holds vast tracts of land in the Pilbara region of Western Australia, about to be opened up for mining. The likely environmental impact of this horrifies Michael’s outspoken teenage granddaughter Madeline (Morgana Davies), who is not quite old enough to take up her allotted seat on the company’s board. Michael insists that, in retirement, his hands are tied. Nonetheless, when the company’s decision is delayed, he finds himself opening up to Madeline as he returns with her to the scenes of his youth; in telling her the half-forgotten story of Mr Percival, he rediscovers something of his original identity as a defender of the rights of wild things.

Taken at face value, this method of updating the story looks bizarrely arbitrary: the contrast between the present-day Michael and the Storm Boy of the past is so complete that connecting the two requires an enormous leap of faith. Moreover, the film’s overt preachiness is not at all in the spirit of Thiele, who expressed concerns from the outset that his environmental message not be transferred to film in a heavy-handed way.[7]Hayes, op. cit., p. 102. Yet, in the context of modern Australian cinema, the approach has its intriguing aspects. It’s suggestive, to begin with, that this framing device closely echoes that in the recent Red Dog: True Blue (Kriv Stenders 2016), in which Jason Isaacs plays another jaded businessman narrator – also named Michael, oddly enough – looking back on an idyllic Australian boyhood.

There is reason to think this parallel may be more than coincidence: both the original Red Dog (Stenders, 2011) and its follow-up take place in the Pilbara, and both are consciously cast in the 1976 Storm Boy’s tradition of realistic yet whimsical Australian children’s films, with the dog of the title taking the place of Mr Percival. The Red Dog movies go out of their way to show the mining industry in a positive light, not surprisingly given that part of their funding came from companies such as Rio Tinto;[8]Jane Albert, ‘Portrait’, The Australian Financial Review, 25 November 2016, p. 19. the new Storm Boy can plausibly be thought of as an ‘answer’ film, though one in which the romanticised ‘purity’ of the young hero is explicitly framed in a context that acknowledges pragmatic twenty-first century realities: co-producer Matthew Street has spoken of the need to find ‘a balance between human society and not over-exploiting nature and natural resources’.[9]Matthew Street, quoted in Sony Pictures, op. cit., p. 6.

Yet a sense of strain is evident in Seet’s film, especially at the conclusion, when the land dispute at the centre of the narrative is set temporarily aside rather than being permanently resolved. The broader question of who ‘owns’ Australia is addressed mostly by implication: that the present-day drama is centred on the Pilbara rather than the Coorong again leaves the two halves of the film curiously separate from each other, effectively situating the Ngarrindjeri people in the past rather than giving them a significant role to play in the here and now. Still more ambiguities emerge when the film is viewed in an even broader context, as an allegory of its own making and of the position of a twenty-first century Australian filmmaker hoping to combine artistic integrity with commercial success. After all, the very act of remaking Storm Boy could itself be seen as a form of exploitation – aiming to reap financial gain from a ‘property’ that, at least in the minds of many viewers, has till now remained pristine.

The very act of remaking Storm Boy could itself be seen as a form of exploitation – aiming to reap financial gain from a ‘property’ that, at least in the minds of many viewers, has till now remained pristine.

If Safran’s film has been idealised in viewers’ memories, Seet’s remake can hardly lay claim to innocence in any sense, frankly displaying its commercial calculations in ways that set it apart from its predecessor. One of these is the prominence given to Courtney and Rush, the two internationally recognisable ‘names’ in the cast, whose characters tend to overshadow the more homely trio of the young Storm Boy, Fingerbone and Mr Percival. Another, unavoidable issue is the availability of digital effects, which widens the gap between what we are directly shown and the ‘natural’ world that is the subject of the drama: even when we are not sure how extensively these have been employed, it is impossible to retain the faith at every moment that the pelicans on screen are real pelicans; the storms, real storms. As if to acknowledge this, Seet shifts the tone of the film incrementally towards fantasy, even taking some hints from current superhero cinema: when a crucial board meeting is interrupted in dramatic fashion by a gathering storm, the hint is planted that Michael may have possessed hidden, mystical powers all along.

This scene also recalls the apocalyptic imagery in Peter Weir’s The Last Wave (1977) – an especially striking connection in light of Noel Purdon’s Cinema Papers review of the original Storm Boy, which proposed that an auteur like Weir might have brought an extra dimension to the project that was unavailable to a journeyman like Safran.[10]Noel Purdon, ‘Storm Boy’, Cinema Papers, issue 11, January 1977, p. 272. It is striking, indeed, how often appreciative discussion of the 1976 Storm Boy gives short shrift to Safran, an expatriate Frenchman who spent much of his career in Australia but nonetheless tends to be labelled an outsider with insufficient spiritual connection to the material. Even Carroll, as the film’s producer, has spoken slightingly of his collaborator as ‘a bit of an arrogant Parisian’[11]Matt Carroll, quoted in Erin Free, ‘Taking Flight: The Making of Storm Boy’, FilmInk, 15 November 2016, <https://www.filmink.com.au/taking-flight-the-making-of-storm-boy/>, accessed 21 November 2018. – though the suspicion arises that, no matter what director had been chosen, Carroll would have considered himself the film’s true auteur.

From this perspective, Safran’s Storm Boy can be taken as a mere approximation of the film that might have been, holding out a promise that Seet and his team have now undertaken to make good on. My own view is the opposite: to my eyes, the self-conscious mysticism of The Last Wave appears overblown and badly dated, whereas Safran’s more prosaic and anonymous style gives viewers more freedom to make the story their own. Seet, for his part, is likewise more journeyman than auteur – and succeeds, as Safran did, in generating nostalgia, at least for adult viewers such as myself. The difference is that this nostalgia is now less for a ‘natural’ childhood paradise than for a less self-conscious brand of fiction: while Seet’s style may not be distinctly individual, it retains a heaviness that may derive from his background in television, his reliance on emphatic close-ups leaving us in no doubt about what the story ‘means’. In the process, something essential seems to have vanished, much as the hero of Thiele’s book vanishes in its opening pages into the storm that gives him his name:

‘He must be lost!’ cried the camper. ‘Quick, take my things down to the boat; I’ll run and rescue him.’ But when he turned round the boy had gone. They couldn’t find him anywhere.[12]Thiele, op. cit.

Endnotes

| 1 | Colin Thiele, Storm Boy, 40th anniversary edn,New Holland Publishers, Sydney, 2002 [1963], Kindle ebook version. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Terry Hayes, ‘Storm Boy’, Metro, no. 197, 2018, p. 104. |

| 3 | See Jake Wilson, ‘In Search of Australia, Then and Now’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 16 January 2018, <https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/movies/in-search-of-australia-then-and-now-20180116-h0izjs.html>, accessed 13 November, 2018. |

| 4 | Thiele, op. cit. |

| 5 | Sony Pictures, Storm Boy press kit, 2018, p. 6. |

| 6 | The setting in Safran’s film was contemporised to the 1970s. |

| 7 | Hayes, op. cit., p. 102. |

| 8 | Jane Albert, ‘Portrait’, The Australian Financial Review, 25 November 2016, p. 19. |

| 9 | Matthew Street, quoted in Sony Pictures, op. cit., p. 6. |

| 10 | Noel Purdon, ‘Storm Boy’, Cinema Papers, issue 11, January 1977, p. 272. |

| 11 | Matt Carroll, quoted in Erin Free, ‘Taking Flight: The Making of Storm Boy’, FilmInk, 15 November 2016, <https://www.filmink.com.au/taking-flight-the-making-of-storm-boy/>, accessed 21 November 2018. |

| 12 | Thiele, op. cit. |