Over the long and storied history of the movie western, there have been hundreds of night-time campfire scenes. Usually signalling a lull in the linear action of the narrative, these moments are rarely the most emblematic of the films they’re in and – with the possible exception of Blazing Saddles (Mel Brooks, 1974) – rarely the most immediately remembered. And yet they are often the most deeply revealing of a film’s subtler textures and psychologies, as though it takes nightfall to blind the characters to the vastness of landscapes that crush them to insignificance, to wrap them in a darkened cloak of intimacy, allowing the blossoming of thoughts and dreams that would burn away to nothing under the hot sun. So it is in Roderick MacKay’s fine, stirring Australian (or ‘meat pie’) western The Furnace, in which the majority of the action – gold grubbing, gunfights and grisly death – takes place during the day, in the arid, fly-swarmed desert outback, but also in which, for just a moment, two characters stray from a companionable circle of firelight one evening and have a short, quiet conversation, about homesickness and how the stars look wrong. It could be a lonesome cowboy ballad, except both are wearing turbans, and they speak Pashto.

‘When you get home, Hanif,’ says one to the other, ‘look at the stars for me.’ Hanif (Ahmed Malek), the film’s protagonist, is a young Afghan cameleer – one of the camel drivers, mostly from India, Central Asia and the Middle East, who brought the animals to Australia in the late 1800s to act as freight transportation across the untamed wilderness before the advent of motorised transport. At this moment, he has just confessed to his companions that, after the death of his friend and father-figure Jundah (Kaushik Das) – the jolly Punjabi cameleer whose shockingly callous murder has set Hanif off on his own journey of discovery – he is thinking of selling his camels and leaving the country. ‘This land has beaten me,’ he tells them.

Given that, more than a century later, The Furnace may well be many viewers’ first encounter with this curious interlude, when dromedaries laden with bales of wool galumphed across Western Australia under the care of minders who brought unfamiliar gods, languages and customs with them from oceans away, is he right? Did Australia beat the cameleers, purposefully forgetting them[1]For more on the cameleers and their historical erasure, see Madison Snow, ‘Australia’s Afghan Cameleers’ Forgotten History Revived by Their Living Relatives’, ABC News, 2 February 2020, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-02-02/descendents-remember-australias-cameleers/11890622>, accessed 23 February 2021. and writing the story of their contributions out of the official history of its foundation? Or is it simply a history that needs to be written on a broader timeframe, scaled to a longer arc of change, one that we cannot see in its entirety right now only because we are still floundering in the middle of it? One of the most interesting aspects of MacKay’s film is that, beneath its relatively straightforward main storyline, and even beneath its underlying, hopeful demonstration of the solidarity that can exist between variously oppressed, dispossessed and marginalised communities, there is a gentle attempt to suggest as much: that the story of modern Australia’s foundation did not end with the crimes of its white colonisers, for which amends, cinematic and otherwise, must now be made. Rather, colonialism and all its attendant brutalities form just one chapter – a bloody, cruel and desperately unjust one – in the unfolding Australian biopic, and there’s a way to go yet before the closing credits roll and the final winners-and-losers tally is in.

It’s a grand claim for a relatively modest film. But the movie western has always been a bellwether not only for the state of a nation’s cinema, but also for the way a society sees itself. This three-way entanglement between cinema, the western genre and national self-identity is almost as old as the medium, dating back to its earliest development – which happened, not coincidentally, around the same time that The Furnace is set. During that early Cambrian explosion period of filmmaking, Australia’s industry was central, at one point producing more films than any other nation.[2]See Australian Film Commission, ‘The First Wave of Australian Feature Film Production: From Early Promise to Fading Hopes’, 15 June 2005, available at <https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2005-06/apo-nid61807.pdf>, accessed 23 February 2021. And many of those movies were proto-westerns, in the form of the bushranger narrative that became prevalent following the enormous success of The Story of the Kelly Gang (Charles Tait, 1906), the world’s first narrative feature film.

The three-way entanglement between cinema, the western genre and national self-identity is almost as old as the medium, dating back to its earliest development.

And so while the genre’s elasticity means that it has transferred with often provocatively fertile results to every corner of the globe, the Australian western can lay more foundational claim to its myths and archetypes than most other nations outside the US. After that high point in 1911, the country’s industry may have entered a long period of relative dormancy – certainly, compared to Hollywood’s decades of ascendancy and supremacy. But that pedigree means there is a double sense of reclamation going on in the new wave of Australian westerns that have recently emerged as the country’s highest-profile and most thematically coherent international successes. The Furnace can be easily bracketed with Warwick Thornton’s stunning Sweet Country (2017), Jennifer Kent’s ferocious The Nightingale (2018), Justin Kurzel’s fascinatingly bizarre True History of the Kelly Gang (2019), and Stephen Maxwell Johnson’s simple and searing High Ground (2020) as collectively representing Australia’s reclamation of the western, as well as individually representing new, twenty-first century perspectives on the nation’s history.

There is even, in Sweet Country, a scene that overtly refers to this longstanding connection, in which the townsfolk gather to watch The Story of the Kelly Gang, and cheer when the narrator indicates the outlaws have escaped ‘the long arm of the law’. Thornton’s agenda in including this moment is subversive – his Aboriginal hero, Sam (Hamilton Morris), explicitly does not benefit from similar outlaw idolisation among the (white) townspeople – but the broader point stands. Certain aspects of Australian identity have shaped and been shaped by the mythos of the western – especially the anti-authoritarianism, grey morality and romantic machismo of the bushranger subgenre – more fundamentally than perhaps anywhere outside the continental United States.

Into this crucible comes The Furnace. On its surface, and presumably by design, it’s a less confrontational, challenging watch than most of its brethren. But, in some ways, its remit is more difficult and more complex. Sweet Country artfully retools the western to feature an Indigenous hero; The Nightingale complicates its revenge narrative with trenchant class, racial and especially gender observation; and True History of the Kelly Gang leans hard and punkishly into the queer aspects of the Ned Kelly myth. But MacKay’s film – impressively ambitious for a debut – attempts a tricky, multifaceted reappraisal of the country’s racial history, one in which the dichotomies of Black/white, coloniser/colonised are complicated by a third perspective. While the film is respectful of the often grim plight of Indigenous characters and cameleers alike at the hands of white settlers, it also casts them in reference to each other, bypassing white involvement altogether. But the complex hierarchies and alliances don’t end there: the cameleers are foreign to both the whites and the Aboriginal peoples not just in religion, culture, speech and skin colour, but also in the temporary nature of their relationship to Australia. They have come with the intention not of assimilating or putting down roots, but of making their fortune, then returning to waiting wives and children and parents, back where the stars are the right way up. When Hanif’s Badimia friend Woorak (played by The Nightingale’s breakout star Baykali Ganambarr, once again bringing a lovely warmth and humour to his role) tells him huffily, ‘We have no faraway land to run to,’ he is partly pouting about Hanif’s perceived rejection of his offer of a home with his people. But he is also pointing out the curious truth that sets Hanif apart both from his people and from white Australians: Hanif has, however notionally, another place he can go.

First, though, he is here to make his fortune, an aim that initially means his motivations are more akin to those of the white settlers who treat cameleers as useful (if contemptible) lackeys than to those of his Indigenous friends. And fortune, illegally gained and ignobly pursued, soon shows up in the form of the wounded Mal (David Wenham) and his two stolen bars of Crown-marked gold. Hanif – admirably played by Malek as callow and conflicted rather than overtly heroic – makes the first of a series of self-centred, unlikeable decisions when he throws his lot in with Mal, even though that means turning his back on his Aboriginal friends and exploiting the collegiality of his cameleer comrades. For his part, Mal, played with impressively committed unwholesomeness by Wenham, is an unredeemed outlaw, a dying desperado and an inveterate racist – even his rescue from death’s door by Hanif, Woorak and tribal elder Coobering (played by a charismatic and commanding Trevor Jamieson) does nothing to lessen his bigotry. In time-honoured John Fordesque tradition, he has a violent past, having participated in the Kalkadoon Wars – a real-life historical event that culminated in a massacre.[3]See Kim Bullimore, ‘Honouring Early Aboriginal Resistance’, Red Flag, 25 January 2019 <https://redflag.org.au/node/6663>, accessed 25 February 2021. And like many a Hollywood cowboy, he self-medicates his guilt away – not with whisky, but with opium – and, when in a thoughtful mood, dispenses nuggets of bitter nihilism. ‘No grace of God out here, my son,’ he jeers at Hanif, who is struggling with the loss of his Muslim faith, his prayer mat still stained with Jundah’s blood. ‘Just the land and all its spoils.’

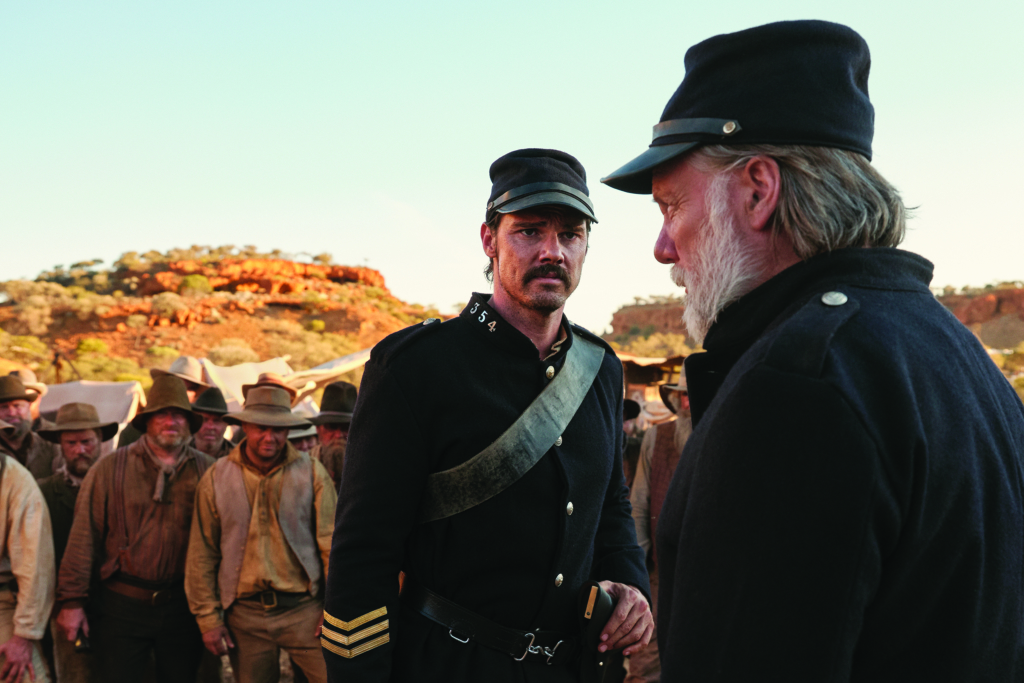

Inasmuch as the film ascribes any philosophy to its prominent white characters, this is it: an ethos based on the wilful erasure of past sins and a rejection of tradition and spirituality in favour of the immediate earthly rewards of wealth or status. Mal’s grasping godlessness is the cornerstone of his character. But other white characters, such as the pursuing ‘Gold Squad’ policeman Sergeant Shaw (Jay Ryan), are also depicted as largely lacking in ideology, belief system or principle – in direct contrast to the non-white characters, whom MacKay’s screenplay is careful to show at prayer or otherwise involved in ritual or acts of remembrance. Shaw refuses to bury the dead bodies he finds along the way; twice over, Hanif goes to some lengths to give dead men an honourable, respectful send-off.

The closest we get to understanding Shaw’s motivation is in his tough-love speech to his greenhorn son, Trooper Sam (Samson Coulter), when he tells the timid teenager that this posting will enable them to ‘make something’ of themselves; again, he is not impelled even by a true sense of duty, or loyalty to the Crown, but by the prospect of social advancement. And when that sentiment is echoed by Hanif, who more than once talks of wanting ‘to be [his] own man’, the story’s overarching framework becomes clear: it is little less than a battle for Hanif’s soul. With his teetering faith and occasionally dubious ethics, it hangs in the balance whether he will reconnect with the idea of something larger than himself – be it his own Afghan heritage or the belief systems of Woorak’s mob – or end up replicating his recalcitrant new father-figure Mal’s lonely, rootless brand of avaricious self-interest.

The Furnace is rendered in grand images that flatter the expanses of baked earth and crushing sky without romanticising away the scrubbiness, the dustiness, the goddamned flies.

Many of the genre’s values – its individualism, its masculine, granite-jawed, man’s-gotta-do impulses – spring from that exact romantic notion of a man making himself anew. That requires, however, that he jettison what he once was. So it is no wonder that the classical western – for, despite its revisionist outlook, The Furnace is defiantly classical in form, up to and including Mick McDermott’s handsome, stately cinematography – has traditionally had such difficulties coming to narrative terms with the historical reality of pre-existing Aboriginal societies. This may even be one of the foundational tensions that make the western so endlessly fraught and fascinating: the genre grows out of an entirely notional, conceptual ‘west’ as an untouched, empty frontier landscape on which a man can set his mark with nothing but his will as his lodestar. But those landscapes never were empty, and indigenous peoples, with their deep-rooted, symbiotic relationships to the land, as well as their various traditions of ancestor worship and tribal memory, are by their very nature an existential contradiction to the kind of blank-slate, forge-your-destiny forgetfulness that powers the genre’s mythology.

That tension exists in The Furnace in less obvious ways too, as MacKay seeks to use traditional western forms to tell a story that is inherently discomfiting to genre norms. And, at times, this attempt to write historical realities back into a set of myths that never had much to do with historical reality in the first place comes at the expense of the film’s drama and urgency. Despite the requisite shootouts and showdowns, the film is slow in tempo, sometimes feeling a little constrained and overcautious. And other extraneous elements are bitten off only to prove rather too big to chew. The second set of pursuers – the ‘demon’ Yates (Goran D Kleut) and his unnamed Aboriginal tracker sidekick (Sean Choolburra) – are arguably unnecessary, especially when they are characterised in such an incongruous, Gothic-melodrama way. The father–son dynamic between Shaw and Sam is never quite developed enough to convince, even if fatherhood does serve to humanise a character who could otherwise lack dimension. And while MacKay is rigorously respectful in the depth and differentiation granted all his cameleer and Indigenous characters (even performing a small act of preservation in ensuring the Aboriginal language spoken is Badimaya, whose last native speaker died just before filming began[4]See ‘About the Production’, The Furnace press kit, 2020, p. 6.), the same can’t really be said of the band of opium-dealing, gold-smuggling Chinese outlaws who guard the eponymous smelting kiln. Aside from featuring the film’s only notable female role – another slight blind spot, if by and large an understandable one – the characterisation of this community lacks some of the compassion and cultural sensitivity MacKay so ably demonstrates elsewhere. (For a more nuanced portrayal of East Asian migrants in the nineteenth-century New World, Kelly Reichardt’s 2019 slow western First Cow comes highly recommended.)

But these few stylistic and narrative flaws aside, MacKay’s is an extremely accomplished first feature, rendered in grand images that flatter the expanses of baked earth and crushing sky without romanticising away the scrubbiness, the dustiness, the goddamned flies. And its delicate act of reclamation ultimately moves in a very gently subversive direction that, maybe even more than Australia’s other recent celebrated westerns, works to categorically shift the focus away from the whiteness encoded in the genre’s DNA. It’s not that The Furnace radically reinvents western storytelling. But in positioning its happy ending as a Muslim Afghan hero’s triumphant abnegation of white settler society in favour of the traditions of Australia’s Indigenous peoples – with Hanif even going so far as to perform his own self-imposed walkabout as a kind of initiation – it does signal that the western’s almost invariably white perspective on Australia’s history is by no means the only one, and acceptance into the colonisers’ social framework is by no means the only metric of an outsider-hero’s success.

Hanif’s journey – away from Afghanistan and the expectations of his father, through servitude to and temporary corruption by the hard, selfish values of Australia’s colonial arrivals, and out the other side into the waiting embrace of Woorak and Coobering as his new family – is sentimental, but it is also sincere, and sincerely hopeful. It cannot, as but one fictionalised strand in a vast, complex and endlessly revisited history, entirely and immediately reform the landscape of the meat pie western. But it does plant a little seed that will perhaps grow to alter the generic territory just a little, like the clusters of palm trees that now dot Australia’s interior, having sprung from the discarded date stones of cameleers resting under stars that – for a few of them, anyway – finally lost their strangeness.

Endnotes

| 1 | For more on the cameleers and their historical erasure, see Madison Snow, ‘Australia’s Afghan Cameleers’ Forgotten History Revived by Their Living Relatives’, ABC News, 2 February 2020, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-02-02/descendents-remember-australias-cameleers/11890622>, accessed 23 February 2021. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Australian Film Commission, ‘The First Wave of Australian Feature Film Production: From Early Promise to Fading Hopes’, 15 June 2005, available at <https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2005-06/apo-nid61807.pdf>, accessed 23 February 2021. |

| 3 | See Kim Bullimore, ‘Honouring Early Aboriginal Resistance’, Red Flag, 25 January 2019 <https://redflag.org.au/node/6663>, accessed 25 February 2021. |

| 4 | See ‘About the Production’, The Furnace press kit, 2020, p. 6. |