Art may ultimately be all about empathy, but there’s still something strange about seeing someone bluntly unfold the intimate details of their life on screen. The act of storytelling adds a kind of distance, a generalisation of the intimate, and documentaries have always been comfortable playing with their own storytelling structures and perspectives. But there’s also something raw and potent about telling it straight. We’re frequently asked to consider how a story on screen is being told, but that shouldn’t mean that we forget that trying to present one’s experiences in as clear and direct a manner as possible is also a worthwhile – and difficult – artistic endeavour. Formal inventiveness is important, but so is maturity and insight.

Margot Nash’s The Silences (2015) is a story told relatively straight. But its delicate and carefully crafted structure shouldn’t see it overlooked in a documentary environment that loves to embrace films that play loudly and overtly with form. Nash’s approach is subdued and reflective, allowing the film to take its time when examining the tensions and difficulties she faced throughout childhood, without feeling compelled to offer explanations or to reach for broader cultural generalities. Documenting her personal and family history, The Silences has few stand-out moments in terms of narrative. Bookended by some newly shot material, the film chronicles Nash’s parents’ marriage, their lives in New Zealand and Australia, the director’s own childhood and career, and – the element that dominates the film, just as it seems to have dominated Nash’s own life – the family’s struggles with her father’s mental illness.

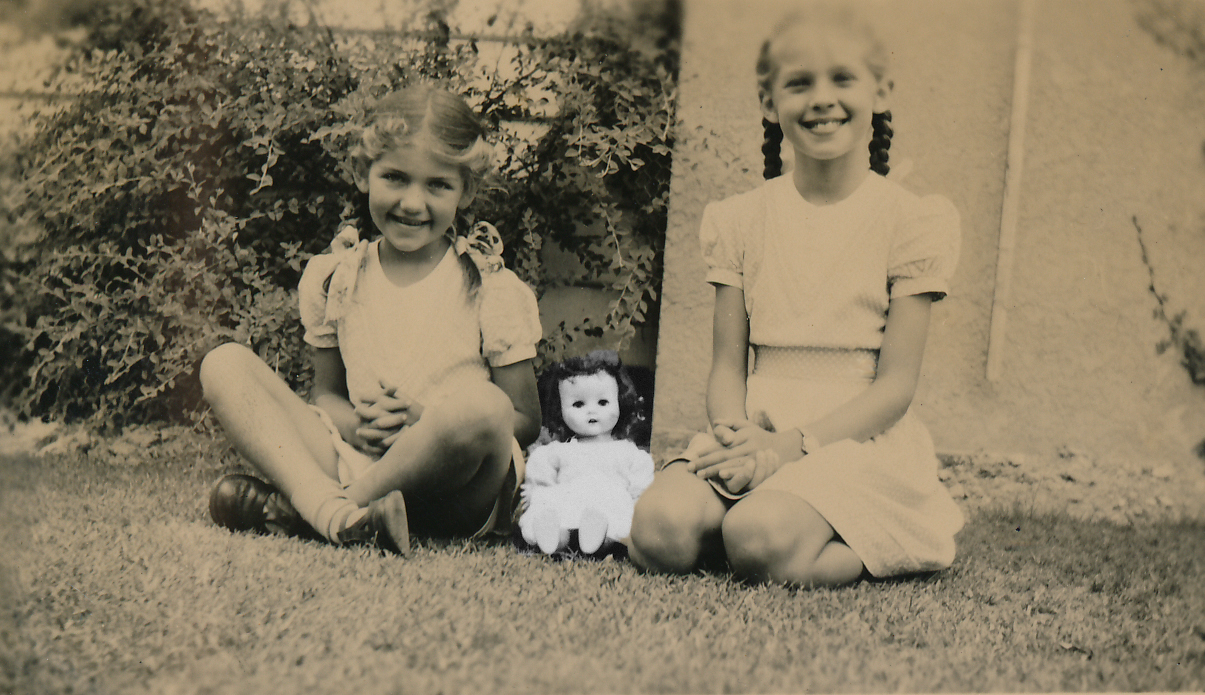

Like most lives looked back on, the key and transitional moments can be small and may stretch slowly and unremarkably over years – or even decades. Nash treats these moments, large and small, with respect and care, even while expressing her memories of frustration and anger. Photos guide the viewer through these family recollections, giving the director a moment to interpret a stance or expression, but also prompting us to wonder what we can really glean about a person from a photo, anyway. Nash inquires: ‘I search their faces; what can photographs tell us about the heart?’ In some ways, this ‘family album’–type approach further accentuates how much of a person’s history relies on such small, almost throwaway, moments of representation. Through these faded photos and letters, along with memories recounted via voiceover and some brief audio clips, Nash builds up the lives of her mother and father.

It’s Nash’s attempts to explain, understand and document her own experiences with mental illness, however, that truly define the film, and which shape and preoccupy the lives shown on screen. In this sense, The Silences is about awareness and lack of awareness – the moments of clarity and the unspoken dreams and fears that fill the spaces of suburban houses and backyards.

While Nash doesn’t demonise her parents – in fact, she spends considerable time painting a picture of their lives, desires and frustrations – neither does she attempt to shape a simple positive message from her experiences. With its empathetic but stoic narration, The Silences seems both a form of personal therapy and a study in childhood powerlessness and entrapment. The film, wisely, doesn’t attempt to seriously diagnose or psychoanalyse Nash’s parents, and her entrapment takes on a broader quality that might have been felt by any child beginning to feel held back from the world around them. This sense of entrapment, perhaps unavoidably, seeps out to encapsulate the suburbs of twentieth-century Australia and New Zealand as seen in the documentary, portraying a world that is, with occasional exceptions, confined and also filled with its own distancing silences.

The sense of this terrible power imbalance between a parent suffering from mental illness and a child is one of the strongest elements of the documentary. While Nash may have taken on a position of power as the storyteller of her own past, the tale she recounts emphasises the powerlessness of children and the awareness that they have to construct from and around the silences in their lives. Just as gutting as Nash’s partly formed awareness of the mental illness in her family as a young child is the revelation that her older sister – at the time, just a child herself – was inducted into the clumsy adult ‘understanding’ of the problem, though instructed to leave her younger sister in the dark. The outcome seemed to be the same either way: whether through enforced ignorance or conspiratorial whispered knowledge, the Nash family home was encircled by reticence and restriction. Even the sisters, notionally suffering together, were split apart by the impossibility of connection and discussion. Scattered audio lets us know that Nash’s sister suffered throughout childhood in her own way. But Nash, wisely, doesn’t try to tell that story.

It may be reductive to refer to The Silences simply as a film about mental illness, but the documentary coincides with some (hopefully ongoing, albeit shaky) steps in the media and in politics towards increased awareness about and discussion of mental health in society. While the social stigma and underlying fear of mental illness has yet to be fully addressed, there remains, at least, an identifiable willingness to engage with the issue in certain areas of the mainstream media. For the last two years, during Australia’s annual Mental Health Week in October, for example, the ABC has presented numerous broadcasts designed to increase public understanding under the banner of Mental As. These programs have included the largely political panel show Q&A, which focuses that week’s episode on mental health; investigative shows exploring real-life stories; and Friday Night Crack Up, which uses a live variety-show format and copious minor celebrities to make the topic about as twee and inoffensive as possible.

Increased awareness can only be a good thing, but narratives focused on destigmatisation – essentially, positive propaganda, in the best sense of the term – can’t help but leave gaps. Of course, there are the overt problems: the downplaying of an ongoing presence in many people’s lives to a single week and, most pressingly, the inherently political issue of the lack of funding and resources to directly support people afflicted with mental-health concerns. Looking at it from the perspective of cultural narratives, there’s the problem of singularity and a tendency to present stories along the lines of what disability activist Stella Young called ‘inspiration porn’.[1]See Stella Young, ‘We’re Not Here for Your Inspiration’, The Drum, ABC, 3 July 2012, <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-07-03/young-inspiration-porn/4107006>, accessed 11 February 2016. Positivity may destigmatise, but it can also reduce and misrepresent the lives of people whose experiences can’t be neatly compartmentalised into those ‘positive’ narratives. The pursuit of the universal – the socially shaping narratives – can neglect intimately personal narratives, which may require a more nuanced or even negative understanding of human experiences.

As such, less-positive narratives that grapple with daily frustrations and the impasse of power imbalances may have less opportunity to be presented in a media context aspiring for a broader positive social narrative. But the importance of the personal narrative can’t be underestimated in these circumstances: social awareness can perhaps be constructed, but the multiplicity of individual human experiences must help inform the more abstract understandings we live by. Awareness and diagnosis are not cure-alls, and it’s vital that stories about the difficulties and frustrations of living with mental illness are chronicled and communicated alongside destigmatising narratives.

In this sense, The Silences is particularly potent because, for the most part, it avoids making those broad positive statements. There’s little attempt to persuade the viewer that the story being presented will have larger cultural ramifications or that the characters involved are particularly emblematic of society at large. The experiences are Nash’s, or her interpretation of others’ experiences, and her narration keeps the immediacy of the context grounded and focused. In The Silences, we’re drawn to examine ‘my mother’ and ‘my father’, but not necessarily an abstracted notion of ‘mother’ and ‘father’. The story is intensely personal, communicating the insights that Nash has developed over time and letting the audience take them as they will.

Yet this intensely personal approach can, perhaps, pose a problem critically or academically. The Silences can arguably be approached as an example of autoethnography, a form that charts personal experiences but which can also be criticised for not providing a particularly ‘practical’ outcome. This would be a question of how the personal narrative can be ‘abstracted and generalised’ for broader application: how can the intensely personal be made to inform larger questions and problems? This might seem like a largely academic issue – and Nash, a lecturer at the University of Technology Sydney, will have her own conception of the values of intimately personal documentaries – but it’s still worth thinking about what value intensely personal narratives can provide. In terms of autoethnography, Carolyn Ellis suggests that the benefits of a highly subjective approach emerge as readers or viewers ‘determine if a story speaks to them about their experience or about the lives of others they know’.[2]Carolyn Ellis, The Ethnographic I: A Methodological Novel About Autoethnography, AltaMira Press, Walnut Creek, CA, 2004, p. 195. In this sense, an audience universalises and re-personalises instinctively: Nash’s story is inherently and unapologetically personal, yet it can’t help but contribute to our sense of the universal. In a less academic sense, we might say that it leads us back to the underlying role of empathy in art and, in a social context, the unavoidable benefits of empathetic awareness enabled by engaging with another’s personal experiences.

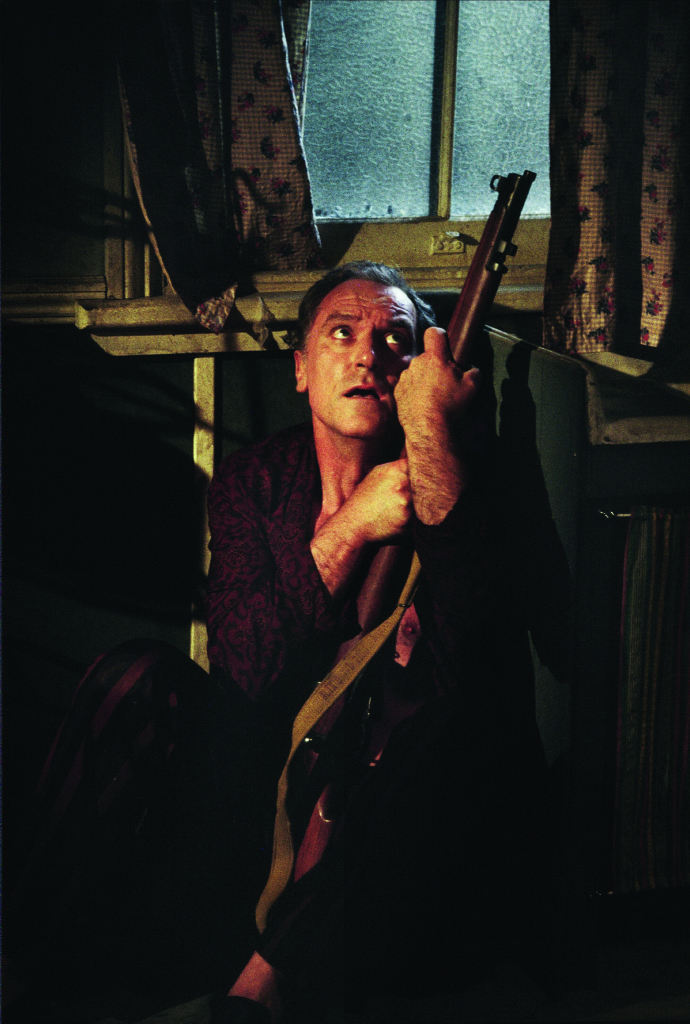

Nash’s story isn’t only one of historical recollection, though. The Silences provides extra cinematic interest through its cataloguing and exploration of the impact that the events of her childhood have had on her work as a filmmaker. The Silences is liberally filled with clips from Nash’s earlier films, seemingly showing a series of fictional surrogates reliving the historical reality being presented to us. This effect is beguiling, and also perhaps intriguingly misleading – Nash herself noted, during a Q&A following the Adelaide Film Festival screening of The Silences, that these clips were only small parts of her earlier works, and her own awareness, while filming, of the connections between her life’s events varied. How much the viewer wants to link these images to the artist’s ‘real’ life remains open, and The Silences should open up a new perspective on Nash’s body of work without limiting it or claiming to encapsulate it.[3]See Edith Mahieux, ‘Discovery-driven Process in Screenwriting – Interview with Director Margot Nash’, When Sally Met Welly, 28 July 2015, <http://whensallymetwelly.com/discovery-driven-process-in-screenwriting-interview-with-director-margot-nash/>, accessed 11 February 2016.

Of course, the fact that Nash is an experienced Australian filmmaker[4]Nash’s directing credits include the feature dramas Vacant Possession (1994) and Call Me Mum (2005), and in 2012, she was filmmaker-in-residence at Zurich University of the Arts. will be a revelation to many. That’s no slight on Nash’s career, but rather a reminder of Australia’s tendency to underappreciate its own filmmakers and film history. As well as providing an important personal viewpoint on mental illness in Australian society, The Silences offers a glimpse into one part of Australia’s underappreciated creative history. It’s a valuable and potent way to introduce many viewers to questions about the intersection of experience and creativity.

Hopefully, the documentary also becomes a reminder of film’s role outside of mainstream narratives – Nash presents her cinematic goals as clearly political, reminding us yet again how reluctant mainstream film culture can be to embrace progressive filmmaking, particularly when it comes to the history (and future) of women filmmakers. Indeed, The Silences was originally intended by Nash to be the basis for a fictional feature-length period film and initially scripted as such; its ultimate appearance as a low/no-budget collage of photos, audio, film clips and narration was primarily due to her difficulties finding funding for the project.[5]Margot Nash, ‘Director’s Statement’, in As If Productions, The Silences press kit, 2016, p. 5.

The positive outcome of this is, of course, that The Silences was made as it is: no-budget or not, the film delivers some of the important truths that personal history can offer, which can’t necessarily be contained in narratives that aim for universality. But that positive outcome needs the usual disclaimer: the fact that an experienced director like Nash needed to turn to no-budget production reminds us just how restrictive film culture continues to be, especially when directors choose to tackle their subjects with a slow, direct sobriety, and to focus on difficult-to-market narratives.

Because it’s largely constructed through existing photos and audio, with small amounts of additional filmed material in places, The Silences might offer a template for others, filmmakers or otherwise, when documenting their own personal histories. The online environment provides countless opportunities for people to narrate their lives through media, but few opportunities for careful reflection on those narratives of self. The Silences certainly deserves to be widely seen, if only to serve as an accessible model for using art as a tool for self-reflection, self-knowledge and cultural history. Employed as a template, The Silences might not stretch the technical capabilities of an emerging filmmaker; Nash’s restraint, insight and reflective poise, however, might be somewhat tougher to replicate.

http://www.margotnash.com/#!the-silences/c1p9k

Endnotes

| 1 | See Stella Young, ‘We’re Not Here for Your Inspiration’, The Drum, ABC, 3 July 2012, <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-07-03/young-inspiration-porn/4107006>, accessed 11 February 2016. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Carolyn Ellis, The Ethnographic I: A Methodological Novel About Autoethnography, AltaMira Press, Walnut Creek, CA, 2004, p. 195. |

| 3 | See Edith Mahieux, ‘Discovery-driven Process in Screenwriting – Interview with Director Margot Nash’, When Sally Met Welly, 28 July 2015, <http://whensallymetwelly.com/discovery-driven-process-in-screenwriting-interview-with-director-margot-nash/>, accessed 11 February 2016. |

| 4 | Nash’s directing credits include the feature dramas Vacant Possession (1994) and Call Me Mum (2005), and in 2012, she was filmmaker-in-residence at Zurich University of the Arts. |

| 5 | Margot Nash, ‘Director’s Statement’, in As If Productions, The Silences press kit, 2016, p. 5. |