In the two decades since its publication, Timothy Conigrave’s 1995 memoir Holding the Man has become the urtext of Australian queer narratives. Beloved not just for its sweeping high school romance but also for its unapologetic realism in portraying an era of freedom, change and devastation, Holding the Man has achieved the rare feat of transcending the specificity of its time and place. And, though it is chiefly a book born of its Melbourne private-school milieu and singular perspective on the AIDS crisis, it has also aged – as a text – into adulthood via theatrical and film adaptations.

On those adaptations’ heels comes Nickolas Bird and Eleanor Sharpe’s 2015 documentary Remembering the Man, a new telling of the beautiful, tragic story of Conigrave and his husband, John Caleo. Depending on how you look at it, Remembering the Man’s arrival in cinemas last year was either clever or inconvenient, with the adaptation of Holding the Man (Neil Armfield, 2015) looming large over it. Viewed in close proximity, the films tell more or less the same tale from different angles and using different modes of storytelling. But Remembering the Man, while superficially secondary in many ways, may well offer the superior version.

Bird and Sharpe’s chief innovation is the use of an archival interview with Conigrave, which forms the film’s structural basis. Conducted by the late James Waites, who was a theatre critic for The Sydney Morning Herald, and found in the National Library of Australia’s archives, the interview allows for a more personal, impromptu account of the couple’s relationship. This renders Remembering the Man perhaps more in line with Conigrave’s original text, which Dion Kagan describes in an earlier issue of Metro as ‘[a]t times guileless and almost documentary’ in approach.[1]Dion Kagan, ‘Telling Our Love Story: AIDS, Adaptation and Neil Armfield’s Holding the Man’, Metro, no. 186, Spring 2015, p. 8. As is often the way, the glossy feel of the big-screen adaptation in some way papers over the rawness of the memoir. But, while Armfield’s film is surprisingly and tactfully frank in its depictions of the narrative’s more confronting elements, such as sex and AIDS-related illness, Remembering the Man’s greatest coup is pushing Conigrave and Caleo’s story past what could be seen as the cinematic culmination of its influence.

Beyond the men

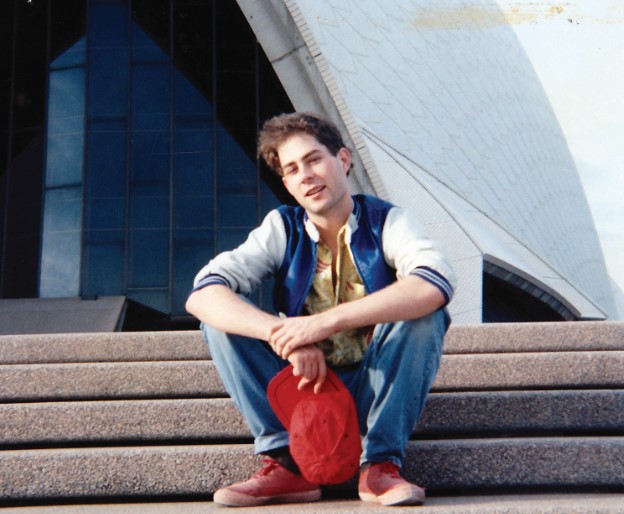

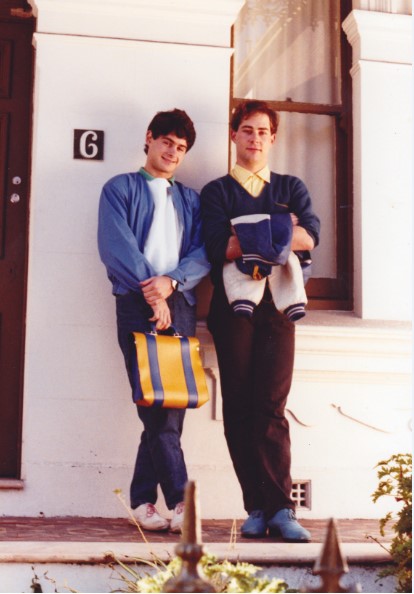

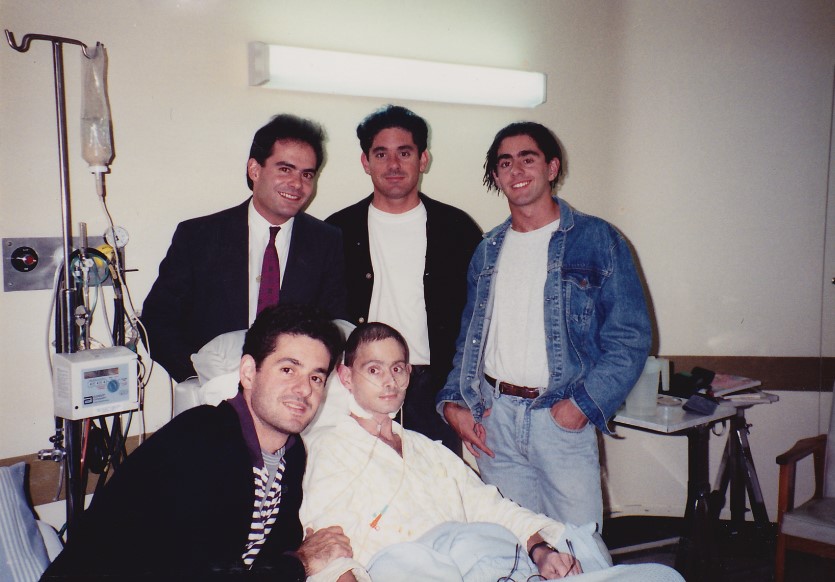

As Holding the Man is Conigrave’s memoir, and therefore his account of their relationship, it has always been the case that Caleo’s perspective isn’t as known to audiences. While this is unavoidable, Remembering the Man goes a small way towards expanding the reach of the story. Though Conigrave’s interview is employed as a throughline, Bird and Sharpe do not let it dominate the film; like in many documentaries of its kind, the directors expand the story by making use of other archival material. With the filmmakers granted access to photographs and video footage of the two men by the Conigrave and Caleo families, Xavier College and the couple’s closest friends,[2]Glenn Dunks, ‘Remembering the Man: New Insights into Tim & John’s Love Story’, Same Same, 24 September 2015, <http://www.samesame.com.au/features/12800/Remembering-the-Man-New-insights-into-Tim-Johns-love-story>, accessed 3 May 2016. Remembering the Man paints an evocative portrait of the pair. This intimate access also allowed the directors to delve deeper into the everyday, more mundane elements of Conigrave and Caleo’s life together.

Photographs of Topolino, the Mickey Mouse memento that Caleo purchased in San Francisco for Conigrave, are particularly highlighted throughout the film – an instant reminder of their connection to each other. The plush toy is an almost-perfect encapsulation of their relationship, and it’s privileged by the documentary to great effect: it reminds the audience that the couple’s memories are both youthful and timeless. With similar impact, Remembering the Man makes a point of mentioning the fact that Caleo’s funeral featured their favourite song, Depeche Mode’s ‘Just Can’t Get Enough’, which captures the same spirit while also functioning as a comment on audience fondness for this particular story.

These are not the only flourishes Bird and Sharpe employ to embellish the narrative; re-enactments are used to evoke the sense of smallness the couple must have felt in the earliest years of their relationship. Actors portraying their parents are shot in extremely tight close-ups, alternately delivering admonishments and condemnations of their homosexuality. It’s a potent if dramatic device that will particularly resonate with LGBTQIA viewers who have endured similarly crushing conversations throughout their lives. While we know of the eventual acceptance by Conigrave’s and Caleo’s respective families, there’s something emblematic about these reactions, which seem to capture every facet of the difficult coming-out experience.

The interviews in Bird and Sharpe’s film give those outside perspectives prominence, and provide those who were close to Conigrave and Caleo the ability to reflect meaningfully and cathartically on their role in a story that was always bigger than them.

Remembering the Man’s greatest asset, however, is its inclusion of interviews with the couple’s friends. Armfield’s Holding the Man, being adherent to the original book and therefore inherently locked into Conigrave’s point of view, both streamlines and enhances the story. As Glenn Dunks points out in Same Same, Conigrave

had his version of events that was full of rehearsed exaggeration, concessions to the truth and deliberate omissions, as well as [a] habit of merging multiple real people into single characters for the sake of brevity.[3]Glenn Dunks, ‘Film: Remembering the Man’, Same Same, 28 October 2015, <http://www.samesame.com.au/reviews/12925/Film-Remembering-the-Man>, accessed 3 May 2016.

But the interviews in Bird and Sharpe’s film give those outside perspectives prominence, and provide those who were close to Conigrave and Caleo the ability to reflect meaningfully and cathartically on their role in a story that was always bigger than them, but of which they were nevertheless a significant part. The interviews shed light on Conigrave’s career – he is described as an ‘enthusiastic performer’ rather than a great actor, for example – and offer deeper insights into the emotional upheaval that Caleo suffered during the time he and Conigrave were apart.

Troubled nostalgia

One of the reasons this enticingly complex narrative is so compelling is that it encompasses a range of time periods. The couple’s relationship stretched across the emergent political promise of the 1970s and society’s fraught descent into AIDS-related panic in the 1980s and early 1990s, lending the story important historical scope. One of the greatest opportunities afforded to a documentary about these time periods is to delve into the social contexts that buttress a relationship and a situation like Conigrave and Caleo’s.

Bird and Sharpe may have released their documentary around the same time as its dramatised counterpart, but this is not to say that there isn’t value in telling this story again. Whereas Armfield’s film is quite strictly tied to the memoir’s narrative, Remembering the Man engages with more historicised elements, folding in archival footage of protests and detailing the activism undertaken at universities while Conigrave and Caleo were students. Though the film adaptation does go some way towards contextualising the couple’s story, Remembering the Man’s primary goal – perhaps more so than the memoir and its adaptations – is to function as a microcosmic snapshot of the time.

Though the film adaptation does go some way towards contextualising the couple’s story, Remembering the Man’s primary goal – perhaps more so than the memoir and its adaptations – is to function as a microcosmic snapshot of the time.

The greater question to be asked of the Holding the Man story, by extension, is this: could its relevance be due as much to its narrative’s potency as to its lack of comparable texts? The size of the Australian film and television industries has always made it difficult for small, so-called niche stories to be produced. Thanks to a broader, global shift towards diversity, stories that fall outside the paradigm of the white, straight and male are beginning to take greater precedence. There is, nevertheless, a bias towards ‘legacy’ stories such as Conigrave’s: narratives with established commercial appeal, built-in catharsis and an agenda of historical relevance as activism. Here, this rear-vision focus is unavoidable – the tragedy of Caleo’s death, and later Conigrave’s, lies in how concretely historical it is and, at the time, in how medically inevitable it was. While this bias does not make such stories any less valuable, there is an extent to which this approach is becoming clichéd, even though the product itself avoids cliché.

Fortunately, as a documentary, Remembering the Man is forced to anchor its perspective in the present. In this way, it gains a self-reflexive ability to expose the limitations of Conigrave and Caleo’s tale as the symbolic apotheosis of queer Australian storytelling, only exacerbated by the proximity of its release to Armfield’s Holding the Man. Indeed, by tackling the bigger-picture story surrounding the one in Conigrave’s memoir, the documentary is imbued with a different texture that is no less emotionally powerful. One of Remembering the Man’s most potent elements is its inclusion of interviews with those working at Fairfield Infectious Diseases Hospital, the epicentre of HIV/AIDS treatment in Melbourne during those years. In one scene, a nurse recounts his attempt to lighten the mood among patients by delivering medication in high heels, only for it to fall completely flat. This anecdote, and others like it, offers a window into the low morale among patients at the time – an invaluable contribution, particularly in light of the relative paucity of filmic insight into the AIDS crisis as it unfolded in Australia.

Perhaps this shortage can be explained by the fact that the response to the explosion of HIV infections in Australia in the 1980s was far more productive than in the United States, where political impotence caused a massive, crucial delay to research funding and the progression of treatment.[4]See Paul Sendziuk, ‘Denying the Grim Reaper: Australian Responses to AIDS’, Eureka Street, vol. 13, no. 8, October 2003, <http://www.eurekastreet.com.au/articles/0310sendziuk.html>, accessed 3 May 2016; and Allen White, ‘Reagan’s AIDS Legacy / Silence Equals Death’, SFGate, 8 June 2004, <http://www.sfgate.com/opinion/openforum/article/Reagan-s-AIDS-Legacy-Silence-equals-death-2751030.php>, accessed 3 May 2016. A prominent recent example does exist, however, in the form of Transmission: The Journey from AIDS to HIV (Staffan Hildebrand, 2014), which aired on the ABC in late 2015. A component of Hildebrand’s Face of AIDS project, the short documentary contrasts Hildebrand’s interactions with AIDS patients in Sydney in the 1980s with encounters involving people living with HIV in Australia today. It’s a staggering difference, but – alongside Remembering the Man – Hildebrand’s film embodies a stark reminder of what it means to be HIV-positive in developed nations then as much as now.

A global conversation

The number of documentaries about HIV/AIDS across the world continues to grow, and Remembering the Man occupies an interesting position among better-known recent examples. Most documentaries on the topic tend to separate into three strands: the personal, the historical and the political. Films such as How to Survive a Plague (David France, 2012) and We Were Here (David Weissman & Bill Weber, 2011) lean towards the historical, providing detailed insights into a specific time and place, and framing HIV/AIDS activism as one of the LGBTQIA-rights movement’s primary causes. Others, such as Fire in the Blood (Dylan Mohan Gray, 2013) and A Closer Walk (Robert Bilheimer, 2003), have a more political function, examining societal action regarding AIDS and the forces both helping and hindering humanity’s response to what has become a global epidemic. By focusing on the realm of the personal, Remembering the Man is largely more aligned with Silverlake Life: The View from Here (Tom Joslin & Peter Friedman, 1993) and What Now? Remind Me (Joaquim Pinto, 2013).

While each of these films inherently deals with a combination of personal, historical and political themes, it is perhaps Remembering the Man’s attempt to incorporate all three strands in only a brisk eighty-three minutes that results in its feeling slightly less impactful than its ambitions would dictate. Yet Bird and Sharpe’s construction of the film, which they co-edited with Tony Stevens, is delicate and impassioned. The stitching of archival materials together with interviews and other formal elements is moving and insightful, lending the film a eulogistic compassion. It becomes as much a paean to the people close to Conigrave and Caleo, who have kept the couple’s memories alive and vibrant, as it is a celebration of its two chief subjects and a chronicle of a significant if harrowing period in Australian – and global – history.

Situating Remembering the Man among a broader canon of documentary approaches to queer subjects is crucial because, realistically, the discussion around HIV/AIDS has begun to evolve faster than filmmakers can chronicle. An affecting record of a powerfully representative relationship, Remembering the Man is further proof of the overwhelming need for films of this kind. With the advent of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)[5]For more information, see Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations, ‘Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)’, 17 December 2015, <https://www.afao.org.au/about-hiv/hiv-prevention/pre-exposure-prophylaxis-prep>, accessed 3 May 2016. as a countermeasure and its increasing prominence in discussions around HIV/AIDS, it’s more important than ever to remember the past and look at how far we’ve come. With serophobic[6]‘Serophobia’ refers to ‘fear and aversion […] towards people living with HIV’; see the Stop Serophobia website, <http://stopserophobia.org/hiv-aids/#what-is-serophobia>, accessed 3 May 2016. attitudes still pervasive, even within the queer community, and HIV’s prevalence in Sub-Saharan Africa and developed nations around the world, the significance of the awareness that film can create is greater than ever. Bird and Sharpe’s film plays an important part in this conversation while also proving that it needs only to become bigger and louder.

http://www.rememberingtheman.com.au

Endnotes

| 1 | Dion Kagan, ‘Telling Our Love Story: AIDS, Adaptation and Neil Armfield’s Holding the Man’, Metro, no. 186, Spring 2015, p. 8. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Glenn Dunks, ‘Remembering the Man: New Insights into Tim & John’s Love Story’, Same Same, 24 September 2015, <http://www.samesame.com.au/features/12800/Remembering-the-Man-New-insights-into-Tim-Johns-love-story>, accessed 3 May 2016. |

| 3 | Glenn Dunks, ‘Film: Remembering the Man’, Same Same, 28 October 2015, <http://www.samesame.com.au/reviews/12925/Film-Remembering-the-Man>, accessed 3 May 2016. |

| 4 | See Paul Sendziuk, ‘Denying the Grim Reaper: Australian Responses to AIDS’, Eureka Street, vol. 13, no. 8, October 2003, <http://www.eurekastreet.com.au/articles/0310sendziuk.html>, accessed 3 May 2016; and Allen White, ‘Reagan’s AIDS Legacy / Silence Equals Death’, SFGate, 8 June 2004, <http://www.sfgate.com/opinion/openforum/article/Reagan-s-AIDS-Legacy-Silence-equals-death-2751030.php>, accessed 3 May 2016. |

| 5 | For more information, see Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations, ‘Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)’, 17 December 2015, <https://www.afao.org.au/about-hiv/hiv-prevention/pre-exposure-prophylaxis-prep>, accessed 3 May 2016. |

| 6 | ‘Serophobia’ refers to ‘fear and aversion […] towards people living with HIV’; see the Stop Serophobia website, <http://stopserophobia.org/hiv-aids/#what-is-serophobia>, accessed 3 May 2016. |