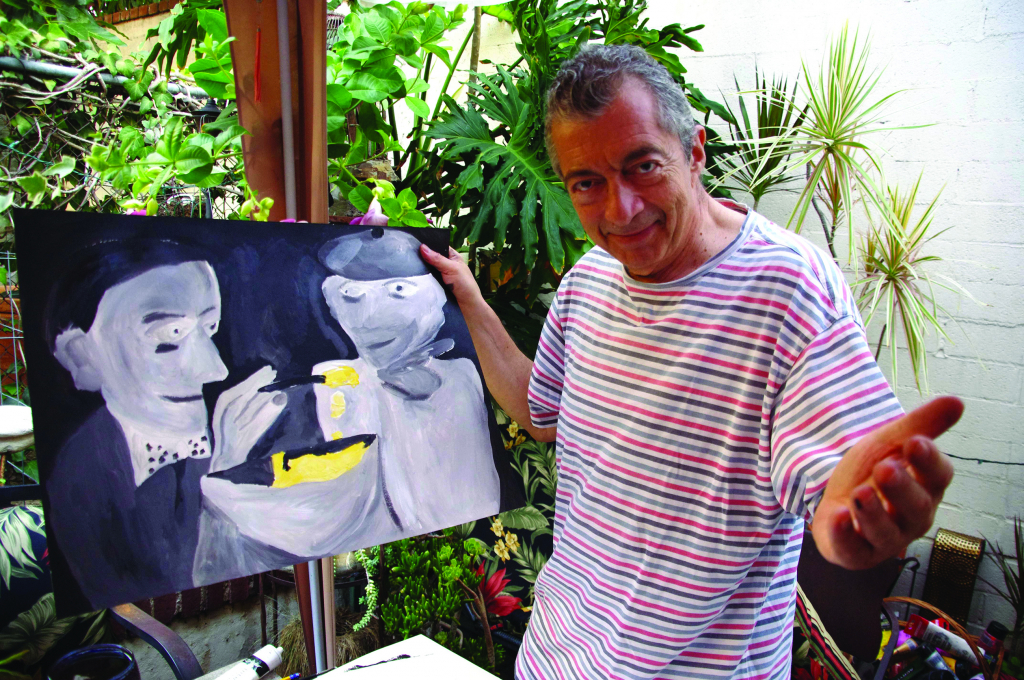

‘That’s your grandfather making mayonnaise on a hot summer’s day in Melbourne,’ says artist Philippe Mora to his son while mixing pink, yellow and white acrylic paint onto board. ‘I’m in the corner, watching, learning how to make it.’

‘The comic book I’m making is called Monsieur Mayonnaise,’ he continues, speaking to us, the audience, in voiceover. ‘It’s going to be about my family in World War II. And the story’s going to be very personal.’

Born in Paris in 1949, now based in West Hollywood and completing this graphic novel, Philippe recently embarked on a journey to discover the true nature of his Jewish family’s path from Nazi-occupied France to Australia in the 1950s. His parents went on to achieve art-world fame with their parties, restaurants and paintings in postwar Melbourne, and Philippe’s mother, Mirka, is an effusive and loving presence throughout the documentary, with clips taken from two days of interviewing her at home, alongside shots of her painting, talking with her son and making mayonnaise. Documentary maker Trevor Graham followed Philippe from West Hollywood, to Melbourne, to Philadelphia and Paris’ Jewish quarter, and the outcome is variously a travelogue, a historical tour and a personal documentary. Like in Graham’s previous film, Make Hummus Not War (2012), in Monsieur Mayonnaise (2016), big political issues are animated by the small things: food, humour and conversation.

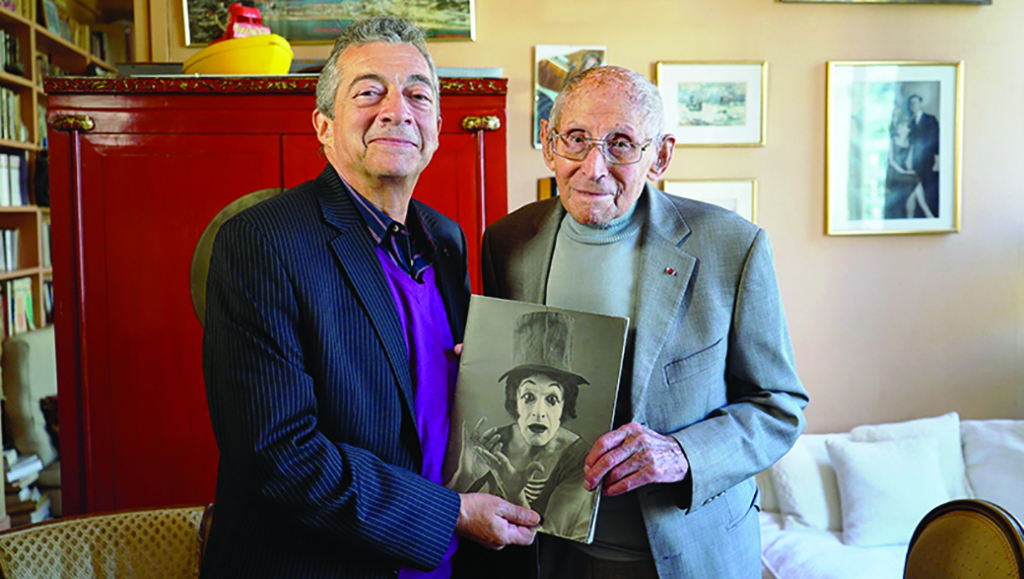

Akin to the SBS series Who Do You Think You Are?, Monsieur Mayonnaise follows a simple mandate: Philippe’s search for the truth of his family’s past and an answer to the question ‘Where do I come from?’ His investigation takes him to the house where his mother hid from the Nazis, to the 105-year-old former Resistance commander Georges Loinget (a cousin of Marcel Marceau, the world-famous mime and Philippe’s godfather), and to the renowned American psychiatrist Henri Parens (who was saved as a child by Loinget). Through Philippe’s narrative voiceovers and the sense that a camera is following him as he travels, Monsieur Mayonnaise constructs a creation myth – a narrative surrounding an individual’s background and origins – using the documentary as a medium for personal storytelling and discovery. It then links that personal family history to larger historical events and themes. With the documentary maker unseen, Philippe takes the on-screen role of narrator, becoming the teller of his own story at the same time as he disentangles and reformulates it.

At the very the beginning of the film, Philippe reminisces about his childhood in Melbourne, and we cut to a close-up of a whisk circling in a bowl, then a painting of the same vision. ‘I begin to wonder: why are you always making mayonnaise, Dad? Monsieur Mayonnaise.’ As the documentary unfolds, the links between this iconic French food, the Mora family, and their history as Jewish refugees and then bohemian artists in Melbourne are unravelled and tied back together.

In his own storytelling decisions as the film’s writer and director, Graham takes two important instructions from Philippe’s artistic and personal disposition. The first is to do with mood: Monsieur Mayonnaise adopts an approach that discusses weighty subject matter with a sense of levity and irreverence. Philippe says in the film:

The idea of joie de vivre is essential to my graphic novel, and it’s the underlying theme. You can either get really morbid and depressed, or you can make comedy, make light of it, enjoy life. That’s the lesson I got from my parents from the Holocaust: live life to the fullest and embrace the good things.

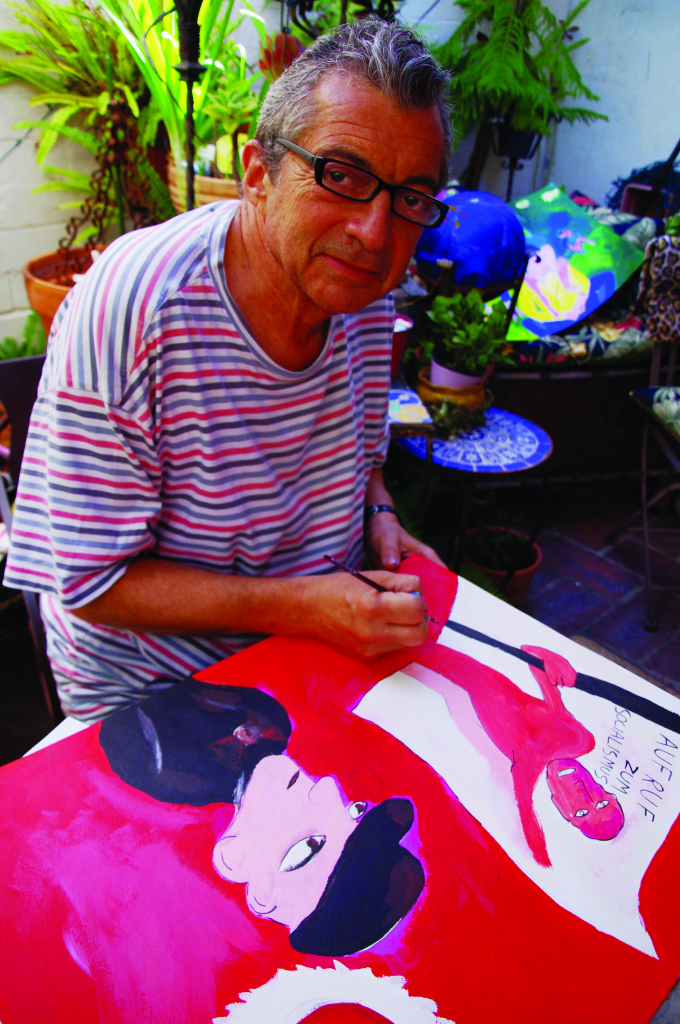

The second relates to the aesthetic expression of this celebratory sensibility: the film embraces the deliberate childlike naivety of the images Philippe creates for his graphic novel as well as that of Mirka’s paintings. The film’s colour palette is bright, saturated and based around primary colours; there is a collage-like approach to editing and, overall, a whimsical and playful visual style. Shots of Philippe’s paintings are an ongoing feature, often shown in extreme close-up while a brush swirls. Philippe has a two-dimensional, cut-out way of representing people, with black outlines around figures making a cartoony impression that combines the comic-book style with a simpler, painterly approach. Adolf Hitler is a recurring figure in these cartoons, his menace and strangeness rendered harmless by the artist’s intentionally ‘primitive’ forms.

Possible readings

A documentary encompassing ruminations on world history, art, food, genealogy and politics, and amassing a wealth of material, will inevitably invite different interpretations. One reading of Monsieur Mayonnaise is that it traces the life and identity of an artist by unravelling the creative threads of that artist’s family history. Regardless of the form of his filmic or painterly outputs, Philippe sees himself primarily as a ‘storyteller’, and introduces himself as such in the film’s opening minutes. In the world of Monsieur Mayonnaise, artists are shown to be sensitive, emotional and offbeat. As Graham said at the 2016 Jewish International Film Festival, ‘The Moras are a very wacky family, and I think that’s self-evident in the film through Mirka and Philippe. They’re a little bit touched with that brush of bohemia and artistic madness.’

Certainly, Monsieur Mayonnaise offers a nostalgic, modernist view of what – or, rather, who – an artist is: a kooky, cockeyed, lovable oddball, driven by curiosity and a search for truth. In the Moras’ case, that view of an artist’s life and disposition is centred on a European background of artistic endeavour, fleeing the trauma of the old world and making work that both bases itself on that trauma and seeks to leave it behind. To see Philippe squirt saturated yellow acrylic paint from the tube and onto stiff paper is to see the vestiges of an entirely different art world: one in which personal storytelling and instinct formed the basis of expression, and in which traditional skills of painting and drawing formed the basis of art-making.

The film’s view of Philippe – a born, instinctive artist, the son of suave European migrants who became key figures in Australian art – finds a precise parallel with popular appraisals of his artistry and his place in Australia’s creative world. For instance, according to Radio National film critic Jason Di Rosso, Philippe ‘had an artistic cultural formation different to most of his peers and, a bit like the Italian-Australian Giorgio Mangiamele, he remains one of our most underappreciated and misunderstood filmmakers’.[1]Jason Di Rosso, ‘Jack Thompson and Jake Wilson on Mad Dog Morgan’, The Final Cut, ABC Radio National, 10 July 2015, <http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/finalcut/jack-thompson-and-jake-wilson-on-27mad-dog-morgan27/6608566>, accessed 9 May 2017. Rather than situating the Mora family’s contributions to the Australian art world among other cultural goings-on and artistic movements, as critic Jake Wilson does in his book[2]Jake Wilson, Mad Dog Morgan, Currency Press, Sydney, 2015. on Philippe’s great contribution to Australian film, Mad Dog Morgan (1976), Graham continues the personal and familial approach established early in the documentary: he reads the works of Mirka and Philippe through their autobiographical details, with the unusual circumstances of their lives providing the keys to understanding their art.

Postwar Jewish migration

An alternative reading of Monsieur Mayonnaise is that it provides a political history of Jewish migration to Australia following the Holocaust, through the much smaller story of the Mora family. This sense of history being played out through the lives of one collection of individuals is a common storytelling device, used in such diverse texts as Mad Men – which offers a history of 1960s America via characters working at an advertising agency – or any number of World War II films, like Schindler’s List (Steven Spielberg, 1993) or Son of Saul (László Nemes, 2015). This dramatic approach allows for large, abstract notions like war to be personalised as we trace the development of characters – people like us – moving through narrative arcs taking place within the much broader arcs of history that are familiar to us from textbooks.

Philippe is an elderly man himself, and his interactions with his mother and his personal-historical tour to Europe are reminders that the Holocaust survivors who remain are the last living ties to this monumental event in world history. Monsieur Mayonnaise documents the memories of these survivors of one of the twentieth century’s defining events as well as the micro-histories of trauma and persecution that rebounded in the decades that followed. In its shots of archival photos of Mora family members’ memorials in Europe, the documentary shows us that there were many Anne Franks, many Schindlers, many more nameless everyday people who engaged in small but significant acts of heroism. The use of archival footage of Europeans in the 1940s and of family photos, particularly a hazy video of a six-year-old Philippe on a Melbourne beach in 1955 in the wake of their migration, brings home this sense of personal closeness to distant history.

The concept of transgenerational and ancestral trauma – that is, the emotional and biological imprint of trauma that trickles down to future generations – is present but not named throughout the film. Though Philippe has no direct experience of the Holocaust, the knowledge of it and its impact on his parents haunt his present. Shots of his West Hollywood home, containing decades worth of debris of a life in art and film, reveal hoarded stacks of books and records concerning Hitler and the Third Reich – Philippe’s lifelong obsession. It is in the final discoveries of Philippe’s trip that the personal and historical link to food comes full circle: we learn that his forebears smuggled their identification documents in the folds of baguettes, smothered in mayonnaise. Like every revelation, this is filmically expressed in shots of Philippe’s paintings for his graphic novel. He learns of the heroic role that his father played with the French Resistance during the war – smuggling children across a river and over the French border for an organisation called the Œuvre de secours aux enfants – and the resulting painting, with its heartfelt naivety and the weight of the story behind it, becomes emblematic of the artist’s journey through history and through his own family story.

Other themes

The terror of survival

One of Monsieur Mayonnaise’s more clearly foregrounded themes is the notion of what happens to the psyches of those who emerge from an unthinkable disaster. When we speak of the Holocaust, we tend to speak most of the millions who died. But, once Philippe meets people who knew his parents in France, his trip reveals an altogether different and elusive war wound: the guilt of survival in those who escaped. The phrase ‘survivor’s guilt’ has become something of a cliché, perhaps impossible to understand for those not personally tied to such atrocities, but those whom Philippe meets are moved to tears, decades upon decades after World War II. They enunciate the irrationality and terror of their own existences compared to those they knew and lost whose lives were just as worthy, and the film stands as a small record of their sorrows – a human-scale expression of huge world events.

Allegory and metaphor in art

Beyond Philippe’s career as a visual artist, Monsieur Mayonnaise makes glancing reference to his life as a filmmaker. The use of the Mora family’s photos and home videos is a recurring motif that finds a powerful juxtaposition when Graham includes some of Hitler’s home videos featuring his partner, Eva Braun, and some young children in otherwise-unremarkable domestic scenes. The footage was taken from Philippe’s own film Swastika, which debuted to outraged audiences at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival.[3]See Richard Brody, ‘The Documentary Swastika’, The New Yorker, 6 April 2009, <http://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/the-documentary-swastika>, accessed 15 May 2017.

As a documentary, Swastika is something of an outlier in Philippe’s filmmaking output, in expression and form – though not in theme. Monsieur Mayonnaise includes a few clips of Philippe’s horror films, including Howling II: Your Sister Is a Werewolf (1985) and Howling III: The Marsupials (1987). Like his paintings and drawings, Philippe’s filmmaking aesthetics are rough-and-ready, transparent in their construction and reveal the involvement of the artist’s own hand. Rather than being hyperrealistic slashers, his horror films are at the schlocky end of the spectrum – think: low-angle shots of monsters in obviously plastic masks – and characterised by what the filmmaker describes in the documentary as an undercurrent theme of ‘persecution’ that attracts him to the horror genre, or what Wilson calls the artist’s continuing concern with ‘violence [and] psychology’.[4]Wilson, op. cit., p. 13. This metaphorical joining of the real-life horrors of the Holocaust with the tacky conventions of the horror genre is explored only fleetingly in this film, but marks an important part of Philippe’s artistic output and the way in which his family history has informed his creative thinking.

The diversity of whiteness

Another, softer background issue the film raises, for me, relates to the historical reasons behind the diverse ethnic nature of whiteness in contemporary Australia and the existence of diverging ethnicities among white people. In the home-video footage commencing the film, Philippe recalls his parents speaking French: ‘Maman, Papa, why are you speaking with that accent?’ Indeed, Mirka and Georges always spoke French, and were part of the Jewish diaspora in Paris and then Melbourne.

Though it is often taken for granted that white people share the same ethnicity and are the monolithic standard against which other ethnic variation occurs, this interlude reminded me that French-speaking Jews were anomalies in 1950s Australia – Philippe tends to give an impression of them as exotic and colourful in their new habitat. They were not Anglo-Celtic like my own (mainly convict) ancestors, and may not have even been considered ‘really’ white in the same way that Irish convicts were considered ‘lesser’ whites than British, or in the way that Italian and Greek immigrants in the same postwar period were considered not-quite-white. World War II induced the movement of many European ethnic groups across the globe, and patterns of migration can shape how we think of race and ethnicity in fundamental ways. American sociologists such as Teresa J Guess have discussed the construction of whiteness and race as social categories in the American context.[5]Teresa J Guess, ‘The Social Construction of Whiteness: Racism by Intent, Racism by Consequence’, Critical Sociology, vol. 32, no. 4, 2006, pp. 649–73. In its own small way, Monsieur Mayonnaise provides a small piece of the migratory history of Europe’s ethnography as it has become expressed in Australia’s own ethnic diversity and in the resulting, shifting social constructions of whiteness.

Despite my ability to pull these more all-encompassing themes from Monsieur Mayonnaise, the film remains firmly a personal project. Philippe’s commitment to an optimistic worldview is given credence with Graham’s decision to end the film with black-and-white footage of Paris’ liberation from Nazi rule in 1944, an enormous crowd of joyous Parisians welcoming the French 2nd Armoured Division. Mirka recalls her migration to ‘Brittany’ and the sight she caught there of a handsome young man, her future husband, Georges. We cut to a rendering by Philippe of his parents in the bloom of their young coupledom, as colourful and uncontrived as an eight-year-old’s painting, before moving onto a photo of Mirka holding baby Philippe, both looking towards the camera. ‘I always held you to face the world,’ she says in voiceover in the film, ‘I want my baby to see the world’ – a generous notion on which Graham has based this small, personal documentary.

Endnotes

| 1 | Jason Di Rosso, ‘Jack Thompson and Jake Wilson on Mad Dog Morgan’, The Final Cut, ABC Radio National, 10 July 2015, <http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/finalcut/jack-thompson-and-jake-wilson-on-27mad-dog-morgan27/6608566>, accessed 9 May 2017. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Jake Wilson, Mad Dog Morgan, Currency Press, Sydney, 2015. |

| 3 | See Richard Brody, ‘The Documentary Swastika’, The New Yorker, 6 April 2009, <http://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/the-documentary-swastika>, accessed 15 May 2017. |

| 4 | Wilson, op. cit., p. 13. |

| 5 | Teresa J Guess, ‘The Social Construction of Whiteness: Racism by Intent, Racism by Consequence’, Critical Sociology, vol. 32, no. 4, 2006, pp. 649–73. |