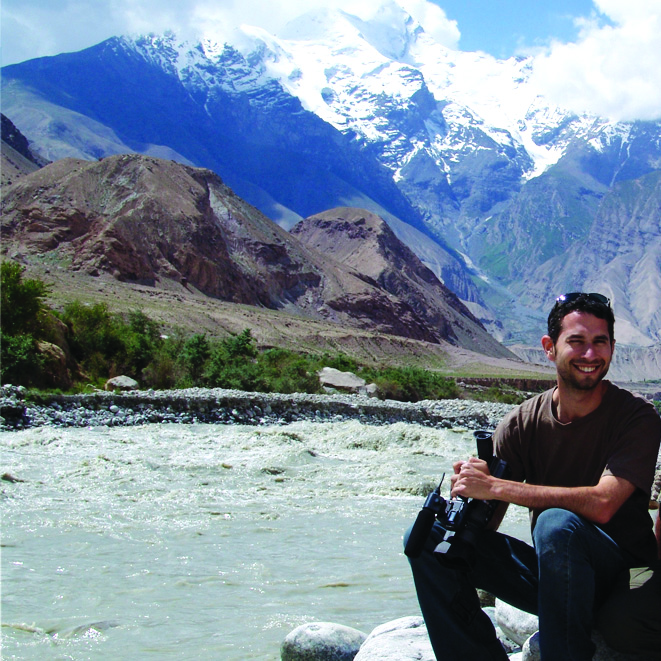

US-born Australian filmmaker and high school teacher Jeff Daniels found himself at the centre of an international incident in August when the Melbourne International Film Festival refused to accede to Chinese Government demands to remove his documentary from the festival program.

The resulting boycott of the festival by Chinese directors and the attacks by Chinese supporters against the festival website and ticketing system were reported widely, drawing significant attention to Daniels’ subject: activist Rebiya Kadeer and the Uighur people of Xinjiang, an oil-rich province formerly known as East Turkestan that was annexed to China in 1949. For the Muslim Uighur, the taking over of their land has brought poverty, human rights violations and a lasting bitterness. Kadeer, who is considered a terrorist by the Chinese Government, has worked tirelessly to promote the Uighur cause and is the staunchest advocate for their self-determination.

RR: The 10 Conditions of Love is an essentially self-funded film that was seven years in the making. Could you tell me some more about its genesis?

JD: I had first heard that there may be Uighur militants in western China after 9/11. I was in New York during that time and I knew people who had died in the towers and it was a very emotional time for my family. So when we heard that Osama bin Laden was perhaps the reason for this happening, we were very emotional. It wasn’t until a few months later that I started to question things that I’d heard, such as that Osama bin Laden may be in China, and that China was running their own battle in the global war on terror to protect us. And by listening to it more, I found there was a whole lot more to the story. I felt a bit manipulated by the Chinese government; I felt that people needed to know the other side of the story. They needed to hear another voice for the Uighur other than the Chinese government.

How did you first make contact with Rebiya Kadeer?

After I’d gone to the region I started trying to contact Uighur exiles who lived in Washington and New York. It took me a while to gain their trust; people who come to them asking questions and claim to be journalists or filmmakers usually end up being Chinese spies, or at least they suspect them to be. After about three years they trusted me enough to introduce me to Rebiya Kadeer, who had just been released from prison. It then took a few more years for me to gain Rebiya Kadeer’s full trust. She really didn’t want me to add the story about her daughter [to the film], for instance. So that took quite a bit of a convincing, and she really doubted my intentions many times. [She wondered if] I was trying to shame her, rather than promote her cause.

What kinds of dangers and threats did you face while making the film?

Probably the most dangerous part of going through the process of filming was that when I visited China, I couldn’t legally state that I was there to make a film about the Uighurs. I never would have been allowed in. I basically presented myself as a tourist, went out into the region and shot tourist footage. Rebiya Kadeer had said ‘you really can’t interview anyone out there, because the first thing that happens is that your camera might be taken away and you may be detained and put on the first plane out of the country, and the Uighur people who you interview will never be heard from again’. Police stopped me many times when I was in China and they would ask me what I’d shot – I’d always show them footage of the people and the culture. So it was very difficult to shoot in that region; there were a lot of questions.

‘When I visited China, I couldn’t legally state that I was there to make a film about the Uighurs. I never would have been allowed in. I basically presented myself as a tourist, went out into the region and shot tourist footage.’

– Director Jeff Daniels

Then after that it was time to interview the Chinese government to get their side of the story. I really couldn’t ask questions about Rebiya Kadeer; it seemed to raise their suspicions. They asked me what I knew about her; they were questioning exactly where I was from and who else was involved in the film, who was funding the film, where it will be screened, etc.

But in fact the people who are screening my film are really getting a lot more threats and seem to be in a lot more danger than I ever felt I was in making the film.

During the making of the film were you always trying to pitch the film to various bodies to get funding?

I tried to pitch it to broadcasters. It seems in my experience with trying to sell this film, that usually if you’re an Australian filmmaker you need to get interest from an Australian broadcaster. My film had no Australian content, so the broadcasters had a reason to deny funding for my film. They said ‘maybe this is more attractive to international broadcasters’. But you go to international broadcasters and they say ‘it sounds interesting – which local broadcaster is interested in this?’, and I’d say ‘well, none of them’, and they’re not very impressed when an Australian filmmaker can’t even get local broadcasting interest. I think this is the case for many independent documentary filmmakers here in Australia who are making films about subjects other than Australia that are pertinent to Australians, as we’re seeing with the controversy surrounding this film.

I believe you eventually got some funding towards the end of the filmmaking process?

After about four years of making the film I received development funding from Film Victoria and that helped me edit a trailer to show to broadcasters. After another three years I got completion funding from Screen Australia. These were relatively small amounts, but enough for me to realistically finish my film. Aside from that, it was greatly self-funded, mainly with money I earned working as a teacher.

What were your personal impressions of Rebiya Kadeer? She seems incredibly strong, though we see hints of desperation and vulnerability in the film. For example, after she does the radio interview: ‘I want to kill myself; I’m going to explode.’

I guess Rebiya really appealed to me – I felt very comfortable with her – because she is an independent woman. My mother was an independent, self-made, competent, successful woman during the eighties in finance; she was really a hero in my mind, so I really felt like I connected with female heroes who were able to take a very strong role not only in business, but also in human rights. These are areas of leadership that we usually see men taking on.

Yes, Rebiya is stubborn – she has to be very headstrong and strong-willed, and I think when you see a person who is like that put into a position like the Chinese government has put her in, where she has to sacrifice the safety of her children in order for them and her people to be free, it’s an amazing situation to see an already incredible woman in. It was incredible to spend three years with her and follow her as she tried to build her organisation and promote her cause.

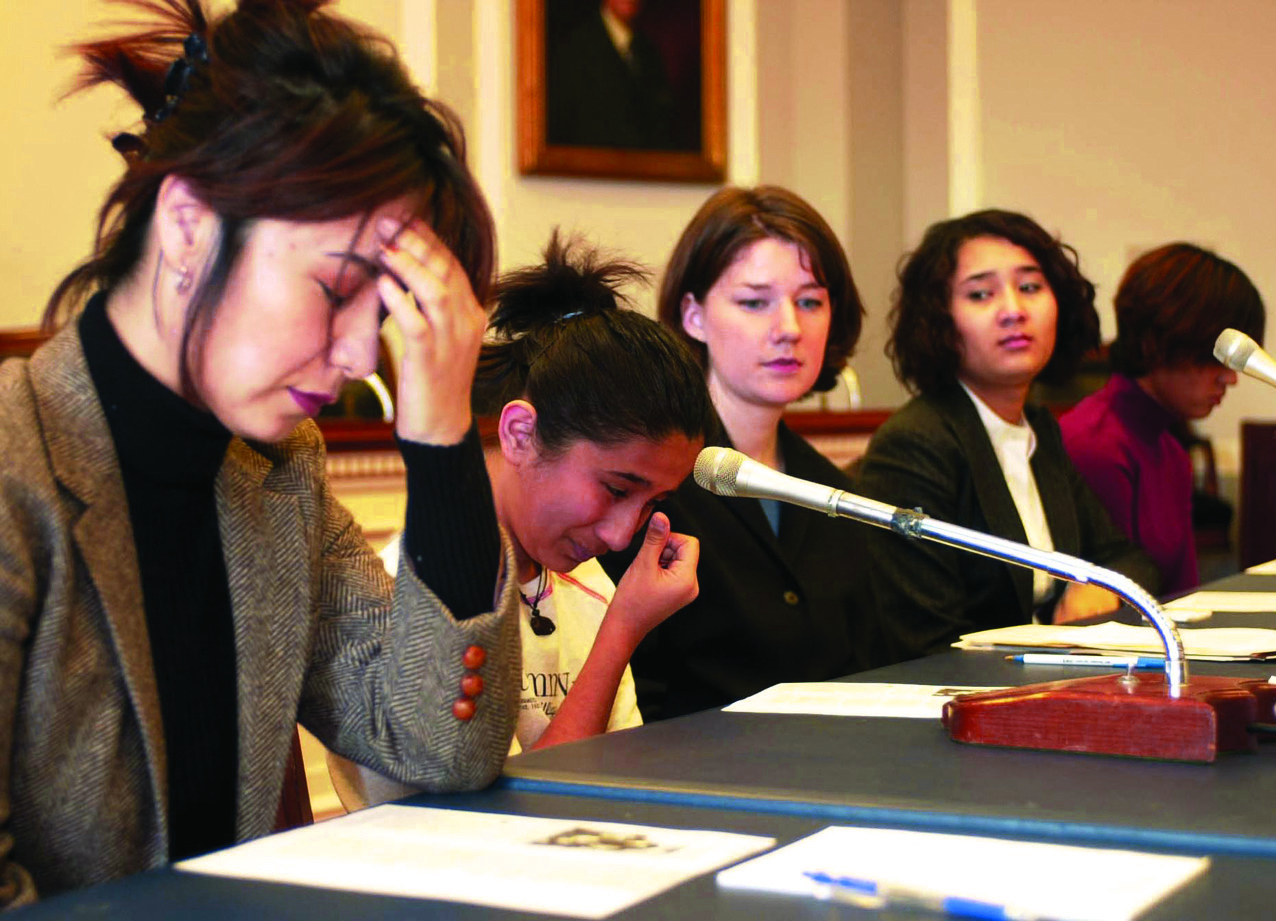

Rebiya Kadeer was head of the 1000 Mothers movement, which worked to improve the lives of Uighur mothers, but her own daughter has mixed feelings about Kadeer as a mother. Was this irony something you sought to draw attention to in the film? Does The 10 Conditions of Love highlight the difficulty for all women – in this case, on a grand scale – of trying to balance work (in this case, very important work) and family?

It was something I wanted to draw out of a leader: I wanted to see the human face of leadership, the story behind the headlines. It happened to be that Rebiya is a woman, and I think that’s very important in terms of women’s studies, and understanding where someone from a minority in China and a woman can actually rise to.

I think that the question of family is not asked of many men; and male, female, if you’re a leader and you have a family, you have to deal with that. How do you get through that? That story really appealed to me. I think by seeing her family, and Ray, her daughter, we’re able to see … her daughter really wore her heart on her sleeve. And you know that Rebiya feels the same way, but given the position she’s in she can’t really express it very much. That’s when you see these really traumatic moments of vulnerability that you’d see from any leader. I speak with my class – there are many different classes at the school I teach at – SOSE, English, Studio Arts, Film – I speak with all of them about the film and we talk about this. We talk about how women are portrayed in film and leadership here. And our kids say, ‘You’d never ask how a man would sacrifice his family for leading his country or leading a cause.’

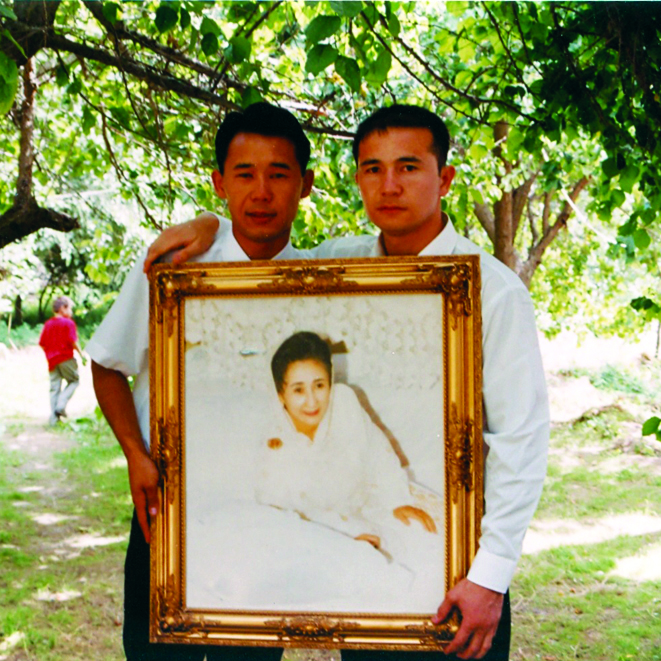

What are your thoughts on her children coming out and saying she masterminded the July 5 riot in Urumqi, Xinjiang?

After people have seen my film they’ll see that Rebiya has also made similar statements on camera – that the unity of the country is the most important, that China is great, that everything she did was bad and was wrong … there are even more videos out there on YouTube now with Rebiya making statements like that. Given the woman who’s presented in the film, and the Rebiya Kadeer that I’ve come to know, I understand that she was put in that position [by the Chinese] in order to get her freedom. I think that Rebiya feels that her children have been put in that same position, and I do believe her. But I think it’s important that we’ve seen Ray’s point of view as well. Maybe yes, they do agree with Rebiya, they do agree with her cause, but they may not appreciate the fact that it’s their mother leading and that in a way they have to pay a price for that.

East Turkestan was annexed to China in 1949, around the same time as Tibet was. It seems interesting that we hear so much about the Tibetan cause in the West and that there seems to be unequivocal support for it, but up until now we’ve heard little about the Uighur cause.

I recently explained this to my class – they’re studying Chinese history, and Asian history in general. It seems that with Tibet you have this image of Buddhism; Buddhism is known to be a very peaceful religion, and so for that reason I think there’s a lot of sympathy for what Tibet’s going through and they find a lot of support in people who believe in independence. But in Xinjiang, you have Muslim people – they’re Sunni Muslim; they’re very peaceful – it seems like Islam is really their identity more than their religion. But they are Muslim, and I think that after 9/11, if you’re a Muslim and you have a gripe with the government, Western countries take a second look at what’s really going on – maybe they can’t completely discount it. I found that because of that difference in religion, there’s a different image that the Chinese government has been able to take advantage of, and it’s really allowed them to justify their crackdown on the Uighurs’ religious practices and culture and their ability to represent themselves.

But also it’s the Dalai Lama – he is the symbol of his people and he has been for sixty years. I don’t think that the Uighur exiles have really had someone who has been as galvanising as Rebiya Kadeer, and she only took the helm as president of the World Uighur Congress about two or three years ago. So I think that’s really now why we’re hearing about the Uighur, because Rebiya is such a powerful leader; she represents her people.

The title of the film refers to the qualities Kadeer wanted in a romantic partner. Why did you choose to focus on the personal in the naming of the film?

I found that it was a pretty endearing story when she was talking about how she’d been chided by her first husband, who chose to become the president of a Communist-run bank and stay married to a wife who was exercising capitalist practices. So it seemed that Rebiya was saying that ‘If I married another man, then he must meet these ten impossible conditions for me to take any interest in him.’ And they were pretty strong demands. He had to be educated – have a tertiary degree – he had to have gone to prison for his beliefs and he had to love his country. And it had to be love at first sight, for both of them. The fact that she actually found someone like that I felt was really incredible; it shows how amazing their union is. So these were ten conditions she put on something that seemed so personal, because of what she’d gone through. She’d already been through a very difficult moment because, in some ways, of the Communist government, and so I guess I felt that this was the position she was put in by them, and she needed conditions in order to love, and ten of them.

The conditions will be explained in further detail on the DVD – we have about three or four of them in the film but they go by very quickly.

The film garnered a great deal of attention during the Melbourne International Film Festival – Chinese nationalists hacked the MIFF website and Chinese directors withdrew their films from the festival. Could you describe what this experience was like for you?

It was pretty surreal, the attention it received. I wasn’t at all surprised that the Chinese Government would disagree with my film being screened, but to make demands on the Melbourne International Film Festival seems inappropriate, naive … I understand that the Chinese Government’s point was that only five days before, they’d blamed Rebiya Kadeer for a violent event that killed 200 Chinese people and that affected thousands of families throughout China. And then they hear that a film about Rebiya Kadeer is going to be shown in Melbourne, that Rebiya Kadeer herself is going to be introducing it – I can understand how they’d be very offended by that. Perhaps some of those emotions made official statements by the government a bit more brash, but continuing to make these statements, continuing to threaten other broadcasters such as Maori TV … they had a meeting with them to try to explain their points, very abrasively. It’s interesting that Maori TV will be showing a film that the Chinese government asked them to show, stating their side of the story and who they feel Rebiya Kadeer is – i.e. a terrorist and a mastermind of violence.

I understand the hate that was going on in China. I was going through a similar thing after 9/11: I was asking questions, I was greatly offended. A lot of messages on my YouTube account for the trailer are saying this: ‘you’ve made us very angry; do you realise what you’ve done? What if we made a film called The 10 Conditions of Osama bin Laden?’ But to actually start attacking the film festival for screening the film, and hacking into their site – I was very surprised by the aggressive behaviour by the Chinese nationalists.

I was glad that they were saying something, because they are trying to communicate – but not in a way where we were hopefully going to have a dialogue. You’re not going to start a conversation by trying to shut another one down. I felt that was what was really the most difficult, seeing the seven Chinese films go. Miao Miao (Cheng Hsiao-Tse, 2008) was the Taiwanese film that the Taiwanese government would rather have had stay in the festival. And then there was Petition (Zhao Liang, 2009) by an independent Chinese filmmaker, a film that is far more controversial than mine. It is about Chinese citizens trying to express their grievances to the government and having them unmet. So to have those films withdrawn didn’t seem to be in the spirit of what a film festival is all about and I felt that that was a great loss.

Regarding the film’s visibility from now on – you’re releasing a DVD with extra footage; will it be on Australian television at all?

We haven’t worked out anything yet, but we’re hoping to seek interest from the ABC and hopefully the ABC will be broadcasting it.

Your press states that you are now making a film about an international Jewish terrorist group. Could you provide some more details about this?

The organisation [the Jewish Defense League] wouldn’t appreciate being called a terrorist organisation. There were a few people involved in the organisation in the late sixties/early seventies who were a bit more militant than others, and did violent acts in the name of the Jewish Defense League, but I think that this is a group that was basically started to prevent another Holocaust from happening. It was founded in 1968, a year when Martin Luther King and Malcolm X were already dead. The US president had been assassinated a few years before, cities were burning in race riots and Jews felt vulnerable. They took up arms and started roaming the streets, trying to protect Jews from anti-Semitism. Then a few got a bit more proactive about that and they became a bit notorious for their acts.

At the moment I’m following a mother and son who are holding the torch for their husband/father who was a former leader of the group, imprisoned for attempting, allegedly, to bomb a mosque in Los Angeles and who committed suicide the day of his trial. They’re now holding the torch and it’s an interesting relationship, this mother and son. The son wants a normal life; he believes in what his father did, and the cause, and has found that his mother can only lead for so long, but also wants to have a normal life.

Where is funding coming from for this film?

I’ve received some development funding from Screen Australia, and we’re hoping to obtain further interest from broadcasters internationally.

Will you continue to make highly political films into the future?

I really never thought of myself as making films that were highly political; I was always more interested in the people behind those stories and what made them tick. It seems that extraordinary people usually attract extraordinary circumstances around them, and so as long as I find that in my subjects I guess I will be making films like that.