Screen adaptations of esteemed novels are commonly beset by tensions. Audiences familiar with the original narrative will naturally use it to evaluate the cinematic rendering, and often find that the film falls short of the source text. This is also informed by the prevailing tendency for literary works to be more highly regarded than film; in the hierarchy of artforms, many consider literature as eclipsing cinema in terms of bearing greater cultural and intellectual ‘value’. As adaptation theorist Linda Hutcheon points out, ‘disparaging opinions on adaptation as a secondary mode – belated and therefore derivative – persist’.[1]Linda Hutcheon, with Siobhan O’Flynn, A Theory of Adaptation, 2nd edn, Routledge, London, 2013, p. xv. This propensity to see screen adaptations as inferior is far from new. In fact, it still chimes with the viewpoint of pioneering British novelist Virginia Woolf, who ‘deplored the simplification of the literary work that inevitably occurred in its transposition to the new visual medium and called film “a parasite” and literature its “prey” and “victim”’.[2]ibid., p. 3.

Joe Cinque’s Consolation (Sotiris Dounoukos, 2016) is a doubly troublesome adaptation because both it and its source material, Helen Garner’s acclaimed book Joe Cinque’s Consolation: A True Story of Death, Grief and the Law, take on a real-world crime that has become nationally notorious. The murder of Joe Cinque in 1997 remains one of the most disturbing middle-class crimes in Australian history. Slain by his girlfriend, Anu Singh, a promising law student at Canberra’s Australian National University (ANU), he was drugged with Rohypnol before being fatally injected with heroin; Singh then watched on as he suffered a protracted death. Despite Singh having told several friends that she was planning a murder-suicide, nobody stepped in to stop her. Her best friend, Madhavi Rao, even helped her procure the heroin. In 1999, Singh was found guilty of manslaughter due to ‘diminished responsibility’; the judge decreed that her mental illness meant she should not be fully accountable for Cinque’s murder. She was released on parole in 2001, while Rao was exonerated.[3]For a full account of the crime and court proceedings, see Libby-Jane Charleston, ‘Crime Week – Bright Young Things: Killer Anu Singh One-sided Suicide Pact with Boyfriend Joe Cinque’, The Daily Telegraph, 5 May 2014, <http://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/crime-week-bright-young-things-killer-anu-singh-onesided-suicide-pact-with-boyfriend-joe-cinque/news-story/930ea54473c90986f4ab1cec234d82b9>, accessed 15 February 2017.

Garner as intervening space

In her account of the trial, Garner placed herself front and centre. She became a kind of moral compass as she disseminated the facts of the crime. She mediated the minutiae of the legal proceedings, the grief of Cinque’s family, the passivity of the friends who bafflingly seemed to enable the crime, the gentle spirit of Cinque himself, the disturbing presence of Singh, and her own musings on what she perceived to be a terrible miscarriage of justice. Garner’s very subjective account of the trial is animated by her fierce intellectual curiosity, along with her desire to connect with the family left behind, and their beloved dead son.

Without Garner’s appalled sleuth, the film lacks emotional coherence … we are offered only a limited understanding of events. While the whys of the crime are the stuff of speculation and armchair psychologising, the film doesn’t really add much to what we already know and feel.

The film’s links to Garner’s novel are tenuous, and seem to speak more to commercial considerations than to preserving the perspective of the source text. Victorian audiences certainly snapped up the opportunity to see it when it premiered at the Melbourne International Film Festival last year, where screenings of Joe Cinque’s Consolation were sold out within two hours of tickets being made available.[4]Myke Bartlett, ‘MIFF 2016 Features a Strong Aussie Lineup’, The Weekly Review, 25 July 2016, <http://www.theweeklyreview.com.au/play/miff-melbourne-international-film-festival-2016-features-strong-aussie-lineup/pub/melbourne_times/>, accessed 15 February 2017. For many, a perverse fascination with the crime is shaped by personal memories of having read Garner’s book, and this allowed the film to create an instant ‘buzz by association’. Yet this immediate appeal isn’t entirely credible. While Dounoukos insists that ‘it was absolutely an adaptation. The world of the book, the tone of the book, except we tried to make Helen’s journey, our journey’,[5]Sotiris Dounoukos, quoted in Jane Freebury, ‘Joe Cinque’s Consolation by Canberra Filmmaker Sotiris Dounoukos Highlights Ambiguities’, The Canberra Times, 23 September 2016, <http://www.canberratimes.com.au/act-news/canberra-life/joe-cinques-consolation-by-canberra-filmmaker-sotiris-dounoukos-highlights-ambiguities-20160922-grmoe5.html>, accessed 15 February 2017. the tone of rage that was transmitted by Garner’s language is absent from the film. Her contemplation brought us in close and held us tightly so that an uncomfortable dialogue at least had a humane axis to swing on. Her writing opened up a much-needed intervening space in which the events of the crime and the court case could somehow be puzzled out; it offered a space for interrogation and reflection.

In fact, much has been made of Garner’s formal exclusion from the film narrative. Many critics and writers have bemoaned her missing voice, but Lauren Carroll Harris summarises it best:

Quite simply, this story needs a Helen – not to be understood, but to be moralised, so that Singh can be defined and judged and Cinque and his extant family can be vindicated.[6]Lauren Carroll Harris, ‘Bearing Witness: Joe Cinque’s Consolation and the Absent Garner’, Kill Your Darlings, 21 October 2016, <https://www.killyourdarlings.com.au/2016/10/bearing-witness-joe-cinques-consolation/>, accessed 15 February 2017.

Without Garner’s appalled sleuth, the film lacks emotional coherence. The omission of that intervening moral space means that we are offered only a limited understanding of events. While the whys of the crime are the stuff of speculation and armchair psychologising, the film doesn’t really add much to what we already know and feel. This raises the question: why make a film about Cinque’s murder, only to replicate what might have happened? Perhaps a documentary might have been better equipped to re-engage with the tragedy on screen?

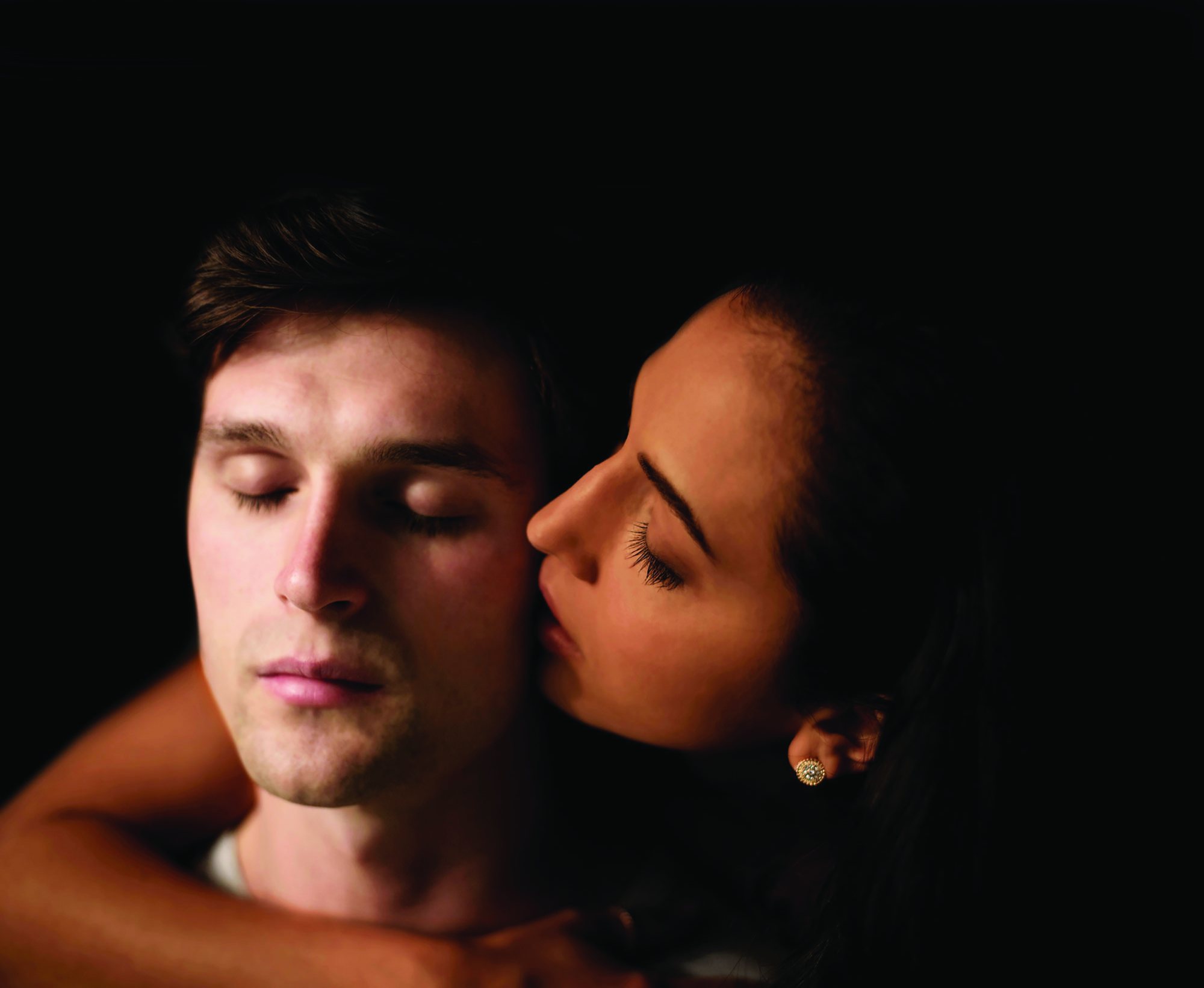

Rather than transposing Garner’s thoughts into a cinematic language that would open up a new discourse around the crime, the film feels disappointingly ‘small-screen’. A colour palette of bright, warm hues recalls the heightened aesthetics of low-budget soap operas. An early outdoor party scene, during which Anu’s (Maggie Naouri) capacity for lies and self-deception is played out, is shot with orangey lighting that makes the garden location look like an artificial indoor set. This ‘look’ recurs throughout the film, jarring with the dispassionate approach that the script seeks to embrace, and what results is a dilution of the emotional and dramatic tensions of a complex story.

Representational storytelling versus embodied cinema

Joe Cinque’s Consolation is trapped by a representational mode of storytelling that occupies a primarily visual register. The effect of this is that we are positioned to passively watch the evolving climate of paranoia and mistrust between Anu and Joe (Jerome Meyer). Anu’s interactions with her friends show us an inert, narcissistic universe, and the resolutely one-dimensional characterisation of protagonists like Madhavi (Sacha Joseph) keeps us contained within the flat parameters of the visual. While this perhaps mirrors the listless moral vacuum that these educated middle-class students inhabit, the diegetic world presented is frustratingly limited.

In the rare moments when Joe Cinque’s Consolation does ‘escape’ the static principles of representational storytelling, we finally sense rather than just see the middle-class horror of the passive bystander. When a cinematic register does emerge, there is a temporary release for the audience that is experienced rather than merely viewed.

Significantly, the concept of ‘representation’ is borrowed from literary rather than film theory, pointing out the disjuncture between media that the Joe Cinque’s Consolation adaptation is caught within. Representational storytelling is a (re)presentation of reality whereby objects, people and places are artificially called on to ‘stand for’ or ‘take the place of’ the material world.[7]WJT Mitchell, ‘Representation’, in Frank Lentricchia & Thomas McLaughlin (eds), Critical Terms for Literary Study, 2nd edn, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1995, p. 11. This highlights yet another tension that exists within the adaptation. The representational mode is more closely aligned with the static written word than the more mobile, multi-sensory address that can be offered up by film. In the case of Joe Cinque’s Consolation, it is as though the narrative and structural conventions applicable to the written word have merely been transposed onto film. Rather than the cinematic form mapping the textual, the reverse is true for the majority of Dounoukos’ adaptation.

Yet, as theorist Jean Mitry points out, the distinction between film and other artistic media is that cinema expresses ‘life with life’:

Whereas the classical arts propose to signify movement with the immobile, life with the inanimate, the cinema must express life with life itself. It begins there where the others leave off. It escapes, therefore, all their rules as it does all their principles.[8]Jean Mitry, quoted in Vivian Sobchack, The Address of the Eye: A Phenomenology of Film Experience, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1992, p. 5.

In the rare moments when Joe Cinque’s Consolation does ‘escape’ the static principles of representational storytelling, we finally sense rather than just see the middle-class horror of the passive bystander. When a cinematic register does emerge, there is a temporary release for the audience that is experienced rather than merely viewed. We start to engage with what embodied film theory scholar Vivian Sobchack calls ‘wild’ communication:

More than any other medium of human communication, the moving picture makes itself sensuously and sensibly manifest as the expression of experience by experience. A film is an act of seeing that makes itself seen, an act of hearing that makes itself heard, an act of physical and reflective movement that makes itself reflexively felt and understood. Objectively projected, visibly and audibly expressed before us, the film’s activity of seeing, hearing, and moving signifies in a pervasive, primary, and embodied language that precedes and provides the grounds for the secondary significations of a more discrete, systematic, less ‘wild’ communication.[9]Sobchack, ibid., pp. 3–4.

When the Joe Cinque’s Consolation adaptation addresses us in this ‘pervasive, primary, and embodied language’, our senses dominate the terms of our comprehension of Joe’s murder. We feel rather than see Canberra’s clinical landscapes. The oppressive weight of privileged anonymity – and the diffusion of responsibility meted out to Anu’s university circle – registers physically as we are enveloped in ominous non-diegetic sound. Fade-ins and fade-outs of public buildings impact on us viscerally, making direct contact with our skins, breaking the safety of distance. They disturb us and implicate us in the wider fabric of a society that sometimes fails its victims. The open spaces of the ANU campus are particularly poignant – devoid of students, the starkly manicured grounds magnify a cultural landscape that breeds that most pernicious social character: the complicit bystander. The slow fade-outs of these images replicate slow blinking and, in doing so, signal the closest connection between Garner’s language and the unique way that we can be positioned to think through film.

In these moments, the film really begins to deliver on its own terms. Here, form and meaning are in alignment, as the privileged drama being depicted widens its scope to look beyond the stasis of the diegetic world. In doing so, it transports us away from the apathy that its protagonists seem to be mired in, and towards the kind of moral condemnation that was arguably lacking from the judicial process. These cathartic moments address our bodies by penetrating the surface of the film; crucially, they disrupt the representational mode that positions us to watch from a safe (but alienating) distance. In making sensorial contact, the film forges a deeper connection with the audience, and opens up a cinematic version of Garner’s intervening space.

The truth in true crime

When Dounoukos is not merely (re)presenting Cinque and Singh’s relationship and the lead-up to the murder, his film is far more powerful. Perhaps the attempt to re-create a reality so utterly alien to the audience only takes us further away through the process of replication; these parts of the narrative are copies of a truth we cannot comprehend. These, however, are undercut by the moments of ‘wild’ communication that precede representation, which open up what Sobchack describes as ‘sense-able’ spaces – situations that let us feel the materiality of the cinematic medium through an embodied encounter.[10]ibid., pp. 6–8.

Such moments of disturbing physical contact are called for in a film like Joe Cinque’s Consolation. They reach out to us in a pre-reflective context and ask our bodies: how removed are you really from the protagonists on screen? They collapse the distance between then and now, there and here, and remind us of our responsibility to one another via the shared humanity of our instruments of perception – our bodies. Released from the representational mode of address, we sense the enormity of Singh’s crime and become immersed in the perplexing sociopolitical context surrounding it.

http://www.joecinque.com.au

https://clickv.ie/w/metro/joe-cinques-consolation

Endnotes

| 1 | Linda Hutcheon, with Siobhan O’Flynn, A Theory of Adaptation, 2nd edn, Routledge, London, 2013, p. xv. |

|---|---|

| 2 | ibid., p. 3. |

| 3 | For a full account of the crime and court proceedings, see Libby-Jane Charleston, ‘Crime Week – Bright Young Things: Killer Anu Singh One-sided Suicide Pact with Boyfriend Joe Cinque’, The Daily Telegraph, 5 May 2014, <http://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/crime-week-bright-young-things-killer-anu-singh-onesided-suicide-pact-with-boyfriend-joe-cinque/news-story/930ea54473c90986f4ab1cec234d82b9>, accessed 15 February 2017. |

| 4 | Myke Bartlett, ‘MIFF 2016 Features a Strong Aussie Lineup’, The Weekly Review, 25 July 2016, <http://www.theweeklyreview.com.au/play/miff-melbourne-international-film-festival-2016-features-strong-aussie-lineup/pub/melbourne_times/>, accessed 15 February 2017. |

| 5 | Sotiris Dounoukos, quoted in Jane Freebury, ‘Joe Cinque’s Consolation by Canberra Filmmaker Sotiris Dounoukos Highlights Ambiguities’, The Canberra Times, 23 September 2016, <http://www.canberratimes.com.au/act-news/canberra-life/joe-cinques-consolation-by-canberra-filmmaker-sotiris-dounoukos-highlights-ambiguities-20160922-grmoe5.html>, accessed 15 February 2017. |

| 6 | Lauren Carroll Harris, ‘Bearing Witness: Joe Cinque’s Consolation and the Absent Garner’, Kill Your Darlings, 21 October 2016, <https://www.killyourdarlings.com.au/2016/10/bearing-witness-joe-cinques-consolation/>, accessed 15 February 2017. |

| 7 | WJT Mitchell, ‘Representation’, in Frank Lentricchia & Thomas McLaughlin (eds), Critical Terms for Literary Study, 2nd edn, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1995, p. 11. |

| 8 | Jean Mitry, quoted in Vivian Sobchack, The Address of the Eye: A Phenomenology of Film Experience, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1992, p. 5. |

| 9 | Sobchack, ibid., pp. 3–4. |

| 10 | ibid., pp. 6–8. |