My favourite ride as a kid was ‘It’s a Small World’, a mainstay attraction at various Walt Disney Company theme parks.[1]For a detailed account of the ride and its famous anthem, see Richard Corliss, ‘Is This the Most Played Song in Music History?’, Time, 30 April 2014, <https://time.com/82493/its-a-small-world-50th-anniversary/>, accessed 10 May 2022. The concept of the ride is simple and lovely. Visitors sit on a boat as it drifts along a river and through seven colourful chambers. Each of these represents a continent, more or less, and is populated by animatronic children in traditional costume who dance, clap and spin as they sing the title anthem, The Sherman Brothers’ ‘It’s a Small World (After All)’, over and over in their respective languages. ‘Though the mountains divide / And the oceans are wide / It’s a small world after all’, goes a section of a verse in English, before the last line merges into the jubilant refrain of the chorus. The voyage lasts roughly ten minutes, and then you queue up and do it again; according to my own unreliable estimate, I’ve sat through it a hundred times.

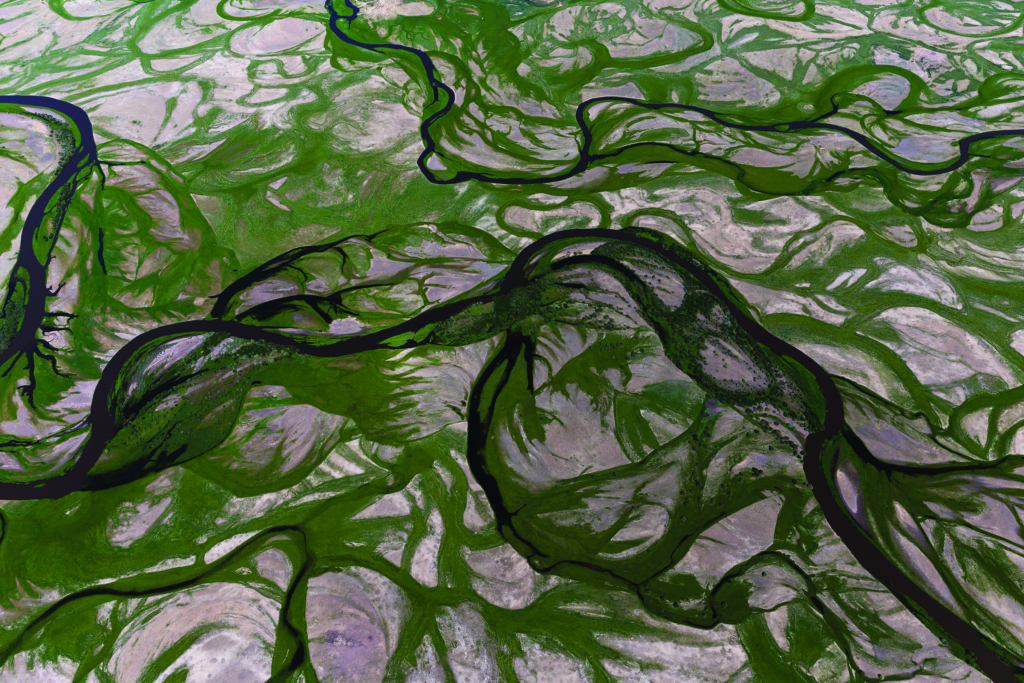

I was reminded of theme park rides in general – and ‘It’s a Small World’, specifically – when I watched Jennifer Peedom’s River (2021), a documentary that ruminates on the beauty, significance and vulnerability of the world’s rivers, and that the director describes as an ode to the ‘arteries of the planet’.[2]Jennifer Peedom, in ‘Jennifer Peedom on Her Film River – An Ode to the Arteries of the Planet’, Uncommon Sense, 3RRR, 22 March 2022, available at <https://www.rrr.org.au/on-demand/segments/uncommon-sense-jennifer-peedom-on-her-film-river-an-ode-to-the-arteries-of-the-planet>, accessed 10 May 2022. It’s an apt description of the interconnectedness of rivers and the myriad ways in which they sustain life; as Peedom’s film shows, these waterways do everything from nourishing ecosystems to providing drinking water and connecting civilisations via transport and trade. As it happens, arteries (or veins) are also what river systems resemble when viewed from above. River spends most of its running time doing just that: it drifts, glides, swoops and soars above and along all varieties of its namesake, mostly from the perspective of drones but also reaching as high as satellites in space. Though it sometimes lands on the ground and even plunges underwater on occasion, River is primarily an airborne film, a film of the twenty-first century.

The film evokes a ride in the way it guides its audience through constant movement, usually following the path of whichever river is being shown at the time. Moreover, its emphasis on spectacle ensures the parallels are not missed. One critic describes a particularly impressive drone shot as ‘rollercoaster-like’,[3]Glenn Dunks, ‘Film Review: River Is a Visual Spectacle’, ScreenHub, 17 March 2022 <https://www.screenhub.com.au/news/reviews/review-river-documentary-1485203/>, accessed 10 May 2022. while several others invoke the mammoth-screened IMAX chain, cinema’s closest equivalent to a roller-coaster experience, when characterising the documentary: River is an ‘old-school IMAX film, designed for enveloping, hypnotic sensation’;[4]Tara Brady, ‘River: Poetic Exploration of the Planet’s Arteries’, The Irish Times, 25 March 2022, <https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/film/river-poetic-exploration-of-the-planet-s-arteries-1.4833337>, accessed 10 May 2022. an ‘Imax-style docu-fantasia’;[5]Peter Bradshaw, ‘River Review: Spectacular Montage-doc Goes to Work on Gushing Waters’, The Guardian,16 March 2022, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2022/mar/16/river-review-jennifer-peedom-willem-dafoe>, accessed 10 May 2022. or, indeed, ‘the best Imax movie Imax never made’.[6]Jim Schembri, ‘Eco-doc River, a Lyrical, Visually Beautiful Ode to the Power and Fragility of Rivers That Mesmerizes – Despite an Unnecessary Narration’, 23 March 2022, <https://www.jimschembri.com/eco-doc-river-a-lyrical-visually-beautiful-ode-to-the-power-and-fragility-of-rivers-that-mesmerizes-despite-its-unnecessary-narration/>, accessed 10 May 2022. Much has been made of how a large screen is integral to the film’s experience, and despite the ubiquity of aerial drone imagery today – now capable of evoking screensavers, car commercials and the most run-of-the-mill stock footage as much as any sort of cinema experience – it’s hard to disagree. As all theme park rides do to some degree, River sets out to exhilarate and induce wonder; and, for this purpose, a large screen always helps.

Though it sometimes lands on the ground and even plunges underwater on occasion, River is primarily an airborne film, a film of the twenty-first century

More pertinent than spectacle, as far as my favourite childhood attraction is concerned, is the film’s global scope and pretensions to universality. River also embarks on an aquatic journey through the world, as it were, traversing a whopping thirty-nine countries in six continents over its seventy-five minutes. Interestingly, most of this coverage was achieved without the filmmakers ever needing to hop on a plane. With their ability to travel hampered by a nationwide COVID-19 lockdown, Peedom and co-director Joseph Nizeti were compelled to scour dozens of archives for material, and outsourced the bulk of the shooting to an informal network of nature cinematographers scattered around the globe.[7]Peedom explains that budgetary limitations meant this collaborative approach would have been required regardless, though presumably to a lesser extent had the pandemic not occurred. See Caris Bizzaca, ‘Podcast – Jennifer Peedom: Making River and Doco Vs Drama’, Screen News, 28 March 2022, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/sa/screen-news/2022/03-28-podcast-jennifer-peedom>, accessed 10 May 2022. Twenty-three cinematographers ended up contributing footage (for which five receive principal credit[8]The five main cinematographers are Yann Arthus-Bertrand, Ben Knight, Pete McBride, Renan Ozturk and Sherpas Cinema, the last of these being a Canadian outfit that specialises in mountain cinematography. Of the combined contributions of the twenty-three cinematographers, it isn’t clear how much of the footage was pre-existing as opposed to newly commissioned.), while archival materials were obtained from a total of sixty different sources ranging from personal media libraries to NASA satellite imagery. Peedom describes her role in the production as more akin to a conductor than a director,[9]Steve Rose, ‘“Rivers Run Through Us”: Willem Dafoe and Robert Macfarlane on Why They Made a Film of the World’s Great Waterways’, The Guardian, 18 March 2022, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2022/mar/18/rivers-run-through-us-willem-dafoe-and-robert-macfarlane-on-why-they-made-a-film-of-the-worlds-great-waterways>, accessed 10 May 2022. and it’s easy to see why.

As is the case in ‘It’s a Small World’, music plays a central role, and it plays nonstop. The film’s soundtrack mostly comprises an original score by Richard Tognetti, Piers Burbrook de Vere and William Barton as well as Tognetti’s arrangements of classical pieces by Johann Sebastian Bach, Antonio Vivaldi and Gustav Mahler – all performed by the Australian Chamber Orchestra, which Tognetti leads as artistic director. (Jonny Greenwood and his band Radiohead also contribute a non-original track apiece, earning themselves some real estate on the film’s poster.[10]Greenwood’s piece, titled ‘Water’, was commissioned by the Australian Chamber Orchestra following his stint as composer in residence in 2012.) The other key ingredient is the voice of Willem Dafoe – Peedom likens it to a musical instrument, while Tognetti compares it specifically to a cello[11]Silvi Vann-Wall, ‘River Director Jennifer Peedom: “Our Attempts to Control Rivers Have Begun to Backfire”’, ScreenHub, 24 March 2022, <https://www.screenhub.com.au/news/news/jennifer-peedom-interview-on-river-1485605/>, accessed 10 May 2022. – who narrates, in deliberate and solemn tones, a script by British nature writer Robert Macfarlane (with additional input from Peedom and Nizeti, who each receive a co-writer credit).

The voiceover occasionally relates information somewhat in the manner of a typical nature documentary. We’re told, for instance, that the largest dams have hoarded enough water from rivers to slow the planet’s rotation.[12]Although it isn’t specified in the film, this fact refers to China’s Three Gorges Dam project, which NASA scientists calculated would increase the length of a day by 0.06 microseconds. See Cutler Cleveland, ‘China’s Monster Three Gorges Dam Is About to Slow the Rotation of the Earth’, Business Insider, 18 June 2010, <https://www.businessinsider.com/chinas-three-gorges-dam-really-will-slow-the-earths-rotation-2010-6>, accessed 10 May 2022. Mostly, it sticks to the task of exuding an all-encompassing admiration for rivers in prose laden with mystical overtones. Rivers are ‘wellsprings of wonder’ and ‘sources of human dreams’ that have ‘flowed through our lives like they have flowed through places’;[13]The latter line invokes the words of naturalist John Muir, who famously wrote that ‘the rivers flow not past, but through us’. Muir, quoted in Linnie Marsh Wolfe (ed.), John of the Mountains: The Unpublished Journals of John Muir, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI, 1979, p. 92. their ‘only purpose is to descend’, but they’re also ‘fickle and unpredictable’ and can help ‘make war and bring peace’, too. River’s voiceover takes the notion of a ‘voice of God’ narration to near-literal levels, and it comes as no shock that even the most ardent admirers of the film have found themselves allergic to it.[14]The narration has been criticised for being ‘overly sanctimonious’, ‘platitudinous and verging on insufferable’, and ‘something even Terrence Malick would have discarded as excessive’; while, in an otherwise glowing response to the film, Schembri suggests that it ought to have been removed altogether. See Todd McCarthy, ‘Telluride Review: River’, Deadline, 5 September 2021, <https://deadline.com/2021/09/river-review-telluride-film-festival-1234827598/>, accessed 10 May 2022; Bradshaw, op. cit.; Dunks, op. cit.; and Schembri, op. cit.

The tone and style of the film places it firmly within the tradition of Godfrey Reggio’s influential ‘Qatsi’ trilogy – Koyaanisqatsi (1982), Powaqqatsi (1988) and Naqoyqatsi (2002) – and other documentaries of their ilk that meditate on the natural world and, by extension, the general state of humanity.[15]Other films in this vein include Baraka (1992) and Samsara (2011), both shot and directed by Ron Fricke, the cinematographer of the ‘Qatsi’ films; and nature documentaries such as Microcosmos (Claude Nuridsany & Marie Pérennou, 1996), Himalaya (Éric Valli, 1999) and Travelling Birds: An Adventure in Flight (Jacques Perrin, 2001). These are non-narrative, big-budget spectacles that share certain features: majestic cinematography, with a heavy emphasis on landscape and generous use of slow-motion and time-lapse; a perpetual score, usually by a respected international composer;[16]For example, the scores for the ‘Qatsi’ films, Baraka and Microcosmos were composed by Philip Glass, Michael Stearns and Bruno Coulais, respectively. and the association of otherwise disparate images taken from an epic variety of cultural, political and geographical contexts. Eminent documentary theorist Bill Nichols categorises such films under the ‘poetic’ mode of documentary, which encompasses many characteristics but generally ‘stresses mood, tone, and affect much more than displays of factual knowledge or acts of rhetorical persuasion’.[17]Bill Nichols, Introduction to Documentary, 2nd edn, Indiana University Press, Bloomington & Indianapolis, 2010, p. 162. According to Nichols, other examples of the poetic mode include Rain (Joris Ivens, 1929), Pacific 231 (Jean Mitry, 1949) and The Maelstrom: A Family Chronicle (Péter Forgács, 1997). With the exception of its religiose narration, River fits the mould.

The film follows even more closely the template of Peedom’s Mountain (2017), which came hot on the heels of her award-winning Sherpa (2015) and holds the honour of the highest-grossing non-IMAX documentary ever released in Australia.[18]The film earned over A$2 million at the box office and sits third overall on the list of highest-grossing Australian documentaries, behind the IMAX films Antarctica (John Weiley, 1991) and Africa’s Elephant Kingdom (Michael Caulfield, 1998). Sherpa sits in seventh place with a gross of A$1.28 million. See ‘All-time Top 10 Australian Documentaries at the Box Office’, Screen Australia, 3 March 2022, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/fact-finders/cinema/australian-films/theatrical-documentaries/top-documentaries>, accessed 10 May 2022. I’m not using ‘template’ in a flippant way here: there really is one, and River follows it almost to the letter, right down to its analogous running time and the fonts duplicated in the credits. The two films share the same main collaborators and were assembled from footage obtained through similar means; they both also open with a black-and-white prologue of an orchestra tuning up, and include comparable archival sequences that provide historical crash courses on their respective subjects. Tonally and structurally, they’re almost indistinguishable: swap out the mountains of Mountain for rivers and you’ll have a fair idea of what River entails. When rivers are eventually replaced by another landform, thus completing the final third of a trilogy that has already been hinted at,[19]In their directors’ statement, Peedom and Nizeti suggest that River is part of a ‘planned trilogy of orchestral concert films that explore the impact of landscape on the human heart’. Peedom & Nizeti, ‘Directors’ Statement’, in Madman Entertainment, River press kit, 2021, p. 3. it’s a safe bet that the same template will be applied once more.

Though Mountain and River may be near identical twins, the latter encounters issues that its elder sibling never had to contend with. Mountains have a distinct shape and are therefore relatively easy to represent. Step back far enough and their beauty and grandeur can be suggested in a single postcard image; hand a kid a crayon and they’ll whip one up in three seconds flat. Rivers are a much trickier proposition, especially to photograph. This is because they’re long, rather than big: rivers go on and on, snaking this way and that, connecting with other rivers and bodies of water, and cutting through vast swathes of land and all the diverse environments that this path entails. They lack the photogenic cohesiveness that mountains possess by birthright. In films, as in real life, even the grandest and most famous rivers are perceived only in fragments, as incomplete stretches of water.

But as River showcases in abundance, it has become possible to capture the sheer, expansive scale of a river – or even an entire river system, even in a single shot – if the camera can get up high enough. The technology that can enable this with relative ease might be recent, but the trade-off is age-old: the higher or farther you get, the more abstract things become. At a certain elevation, rivers invariably flatten into a series of lines and shapes[20]River dedicates a lengthy sequence to such imagery, which the film’s press kit likens to ‘gorgeous artistic renderings of stands of trees’. Madman Entertainment, ibid., p. 6. – the kind of unusual, albeit gorgeous, sight that a bird or an astronaut might admire from above, far removed from what the rest of us plebs can see, hear, touch, smell or catch fish from at ground level. In any event, floating above the earth’s surface has hardly been a convenient option for most of cinema’s history – certainly not for documentaries. Which is why films have relied on a humbler, but tried-and-tested, approach when it comes to these waterways: travel horizontally rather than vertically, to see where the river doth flow.

Early on in River, the filmmakers grasp a golden opportunity to do both at once. The shot in question was filmed in Norway by Ralph Hogenbirk, a Dutch drone cinematographer who goes by the name Shaggy FPV online. Hovering precariously close to the ground for the entire duration of the shot, the drone camera orbits a glacier, latches on to a stream of water released from it, then follows its descent at breakneck speed as it plunges down the rock face and merges with the river below. It’s a virtuosic spectacle made more so by its pairing with Bach’s chaconne from Partita No. 2 in D Minor, which swells to a crescendo in perfect unison with the shot’s trajectory. But it’s also more than just spectacle: the sequence expresses an idea with a clarity and a directness that couldn’t have been achieved in any other way; it offers a genuinely new perspective by allowing us to experience, in an uninterrupted flow, how a river comes to be. At this moment, River proves itself more than capable of matching the poetic gravitas of its narration.

Unfortunately, it proves to be an isolated example only. Once the sequence ends, the film slips into a comfortable routine of cherrypicking and jump-cutting between snippets of waterways, taken from anywhere and everywhere, the sum total of which is an amorphous concept of a river that is meant to encompass every single one of them. Beyond what is shown in a single shot, which is never held for more than a few impatient seconds, we rarely get to see a river flow. On the odd occasion that a river is followed for longer, its path is merely suggested by editing together fragments from downstream, as films have always done, or simply by stating it through the narration, as films have also always done. For all the splendour of its cinematography and the high-tech nature of its collaboration – both very much products of our time – the approach that River settles for is rather conservative and old-fashioned, and contains none of the revelatory power of that drone shot.

The film’s dependence on montage often leads it into muddy waters. For example, a sequence that focuses on Earth’s water cycle – or, as the narration prefers to put it, the river’s ‘reincarnation’ following ‘its death in the ocean’ – begins with the curious claim that ‘the sky has rivers’. It then proceeds through stunning images of swirling clouds (these are the ‘sky rivers’), cloud-covered cities, lightning, rain, sunshine, mountain peaks and then snow, before circling back to rivers via a series of associations that always retain a degree of logic but nevertheless come across as laboured. Elsewhere, rivers link to bridges that connect to freighters that lead to cities, just moments after they sweep us from river workers to industrial-scale irrigation systems via scenes of agriculture in a handful of unnamed countries. I was left wondering if the film might have been better off had it just focused on water in general; at least this would’ve provided a clearer justification for indulging in these sorts of conceptual leaps, without the constant need to check back in on its protagonist. This is the problem with making a film not about a river, but all rivers: the parameters become virtually non-existent, because rivers can be connected to almost anything; they’re so many things at once.

And yet being everywhere and knowing everything remains River’s guiding principle, which is further complemented by a narration that appears to address everybody. ‘As we have learned to harness the power of rivers, have we forgotten to revere them?’ Dafoe ponders in the film’s opening. If ‘we’ refers to all of humanity, then the simple answer might be that some of us have indeed forgotten and some of us haven’t, while some of us never revered rivers and likely never will. Although this sort of vague, universalist rhetoric is not uncommon, especially during times of crisis, River’s narration reminded me of a particular slogan that was repeated ad nauseam in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: ‘We’re all in this together.’ Spruiked by political leaders and parroted by common folk worldwide, this phrase initially seemed to contain some modicum of truth – that is, until it started popping up in marketing campaigns and people cottoned on to the fact that no, the pandemic is not in fact experienced by everybody in the same way.[21]As digital media scholar Francesca Sobande contends, the slogan camouflages structural inequalities in society, while its ‘commodified construction of “we” dismisses the experiences of those who are most at risk and worst affected by COVID-19’. Sobande, ‘“We’re All in This Together”: Commodified Notions of Connection, Care and Community in Brand Responses to COVID-19’, European Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 23, no. 6, 2020, p. 1036.

For all the splendour of its cinematography and the high-tech nature of its collaboration – both very much products of our time – the approach that River settles for is rather conservative and old-fashioned

In truth, River is pitched squarely at comfortable Western viewers, for many of whom a river would be less an obvious source of life or livelihood than one of recreation, and to whom the idea of revering a body of water might sound like a Martian concept. River is, after all, an English-language documentary narrated by a Hollywood star, and part of a franchise (of sorts) that was also designed to be screened in concert halls to the accompaniment of a ‘who’s who’ of European classical music.[22]In her capsule review of the film, Marina Ashioti suggests that the pairing of this music with footage of heterogeneous Indigenous people ‘points towards a historical fixation that the Western world has with “primitivism” – one that fosters a utopian longing for a pre-industrial way of life through a return to nature’. Ashioti, ‘River’, Little White Lies, 17 March 2022, <https://lwlies.com/reviews/river-2/>, accessed 10 May 2022. There’s nothing wrong with any of this – only that River isn’t at all upfront about its intended audience.The film, for whatever reason, shies away from details at every opportunity and offers only vague generalities in their place; it pretends to address everybody and winds up addressing nobody in particular.

Many documentaries can be justly criticised for being too obsessed with information, but River suffers from exactly the opposite problem. In its dogged pursuit of the universal, the film in fact goes out of its way to efface information – or practically any sign of specificity whatsoever. We don’t learn the names of any of these rivers or in which countries they lie, just as we’re never told whom these people and cultures are that are frequently glimpsed in the images or alluded to in the prose. No signposts are provided, and no voice can be heard outside of Dafoe’s blanketing narration. Other than what we can deduce through our own general knowledge, we’re left entirely to our own devices.

This isn’t such a problem when the film focuses on admiring rivers, which it mostly does, but it becomes one when it attempts to press its environmentalist concerns. Like many documentaries worthy of the name, River aspires to do more than just admire its subject: it also issues a warning and encourages us to reflect on the consequences of human behaviour. ‘Look after the river and the river will look after you,’ the narration proclaims, thus voicing what might be considered the film’s key message. But in the absence of any meaningful context through which such a message can be understood and appreciated, let alone acted upon, it becomes diluted to the point of meaninglessness.

When we’re shown a river clogged with plastic waste, for example, viewers may wonder whether this scale of pollution exists in their own backyard or somewhere far away on the other side of the planet. Maybe we’re just meant to know – or maybe it doesn’t really matter because this river, like the rest of them, is supposed to stand in for every other. Elsewhere, the film explains that ‘there’s always a downstream cost’ when humans try to control rivers by diverting them: ‘Somebody, somewhere, must have less.’ It’s a simple and potent idea that can be grasped easily, and explored in relation to all manner of social inequality. Yet there’s no telling whom or where this somebody is, how exactly they’re being affected, or what is being done to affect them, because ‘downstream’ arrives only in the form of time-lapse images of urban sprawl taken from outer space. (The incongruous distance between voice and image here recalls a question posed by Eric Hynes in his oft-cited Film Comment article about drones and cinema: ‘If your film’s currency is intimacy, is access, is humanity, why are you floating above everyone’s heads?’[23]Eric Hynes, ‘Where Eagles Dare’, Film Comment, July/August 2018, p. 48.) Documentaries can’t be expected to offer solutions, but it’s not unreasonable to expect them to clearly state the problem. With nobody to point the finger at, nothing specific to latch on to and nary a context to lean on for guidance, River provokes not action but inaction.

The film does appear to come up with one solution, however, and a very practical one at that. Having dedicated much of its middle section to the topic of dams and their environmental consequences, River culminates in a cathartic sequence of dam walls being blown open with dynamite. As Radiohead’s ‘Harry Patch (in Memory of)’ soars, biblical torrents of water are liberated from behind the concrete, releasing along with them all of the river’s nourishing silt that has been lying trapped and stagnant. Within the space of a few slow-motion images, dried riverbeds are invigorated and entirely new rivers are formed. Birds return to the sky in joyful formation; fish swim once more. While the desire to close a film like this with optimism is perfectly understandable, River’s finale presents cause and effect with such brute simplicity that it registers as nothing less than fantasy; moreover, like elsewhere in the film, the spectacle lulls you into a relaxed, politically disengaged trance. When the credits begin to roll soon after, one can be forgiven for thinking they’ve figured it all out: just blow up the dams and be done with it, already.

‘It’s a Small World’ was conceived in 1964, during an anxious period in history wherein the threat of nuclear annihilation hovered closely above the world’s population. In its appeal for peace, the ride gathered the different places and cultures of the world and placed them side by side, relaying a message of harmony that any child could understand. River was likewise produced during a turbulent time – perhaps more so, given that nuclear weapons have hardly gone away (to say nothing of the fact that the entire planet is now well aware that its potential demise may not even require them). The film makes a similar appeal for unity; only it does so by collapsing the world’s rivers and peoples into a single hazy entity, and by soothing us with the notion that everybody is responsible for everything, and therefore nobody is responsible for anything, because we’re all in this together after all. I’ve no doubt that viewers will walk away from River with a newfound respect for rivers – perhaps even a reverence for them, to the extent that our culture is capable of it. If only reverence were enough.

Endnotes

| 1 | For a detailed account of the ride and its famous anthem, see Richard Corliss, ‘Is This the Most Played Song in Music History?’, Time, 30 April 2014, <https://time.com/82493/its-a-small-world-50th-anniversary/>, accessed 10 May 2022. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Jennifer Peedom, in ‘Jennifer Peedom on Her Film River – An Ode to the Arteries of the Planet’, Uncommon Sense, 3RRR, 22 March 2022, available at <https://www.rrr.org.au/on-demand/segments/uncommon-sense-jennifer-peedom-on-her-film-river-an-ode-to-the-arteries-of-the-planet>, accessed 10 May 2022. |

| 3 | Glenn Dunks, ‘Film Review: River Is a Visual Spectacle’, ScreenHub, 17 March 2022 <https://www.screenhub.com.au/news/reviews/review-river-documentary-1485203/>, accessed 10 May 2022. |

| 4 | Tara Brady, ‘River: Poetic Exploration of the Planet’s Arteries’, The Irish Times, 25 March 2022, <https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/film/river-poetic-exploration-of-the-planet-s-arteries-1.4833337>, accessed 10 May 2022. |

| 5 | Peter Bradshaw, ‘River Review: Spectacular Montage-doc Goes to Work on Gushing Waters’, The Guardian,16 March 2022, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2022/mar/16/river-review-jennifer-peedom-willem-dafoe>, accessed 10 May 2022. |

| 6 | Jim Schembri, ‘Eco-doc River, a Lyrical, Visually Beautiful Ode to the Power and Fragility of Rivers That Mesmerizes – Despite an Unnecessary Narration’, 23 March 2022, <https://www.jimschembri.com/eco-doc-river-a-lyrical-visually-beautiful-ode-to-the-power-and-fragility-of-rivers-that-mesmerizes-despite-its-unnecessary-narration/>, accessed 10 May 2022. |

| 7 | Peedom explains that budgetary limitations meant this collaborative approach would have been required regardless, though presumably to a lesser extent had the pandemic not occurred. See Caris Bizzaca, ‘Podcast – Jennifer Peedom: Making River and Doco Vs Drama’, Screen News, 28 March 2022, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/sa/screen-news/2022/03-28-podcast-jennifer-peedom>, accessed 10 May 2022. |

| 8 | The five main cinematographers are Yann Arthus-Bertrand, Ben Knight, Pete McBride, Renan Ozturk and Sherpas Cinema, the last of these being a Canadian outfit that specialises in mountain cinematography. Of the combined contributions of the twenty-three cinematographers, it isn’t clear how much of the footage was pre-existing as opposed to newly commissioned. |

| 9 | Steve Rose, ‘“Rivers Run Through Us”: Willem Dafoe and Robert Macfarlane on Why They Made a Film of the World’s Great Waterways’, The Guardian, 18 March 2022, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2022/mar/18/rivers-run-through-us-willem-dafoe-and-robert-macfarlane-on-why-they-made-a-film-of-the-worlds-great-waterways>, accessed 10 May 2022. |

| 10 | Greenwood’s piece, titled ‘Water’, was commissioned by the Australian Chamber Orchestra following his stint as composer in residence in 2012. |

| 11 | Silvi Vann-Wall, ‘River Director Jennifer Peedom: “Our Attempts to Control Rivers Have Begun to Backfire”’, ScreenHub, 24 March 2022, <https://www.screenhub.com.au/news/news/jennifer-peedom-interview-on-river-1485605/>, accessed 10 May 2022. |

| 12 | Although it isn’t specified in the film, this fact refers to China’s Three Gorges Dam project, which NASA scientists calculated would increase the length of a day by 0.06 microseconds. See Cutler Cleveland, ‘China’s Monster Three Gorges Dam Is About to Slow the Rotation of the Earth’, Business Insider, 18 June 2010, <https://www.businessinsider.com/chinas-three-gorges-dam-really-will-slow-the-earths-rotation-2010-6>, accessed 10 May 2022. |

| 13 | The latter line invokes the words of naturalist John Muir, who famously wrote that ‘the rivers flow not past, but through us’. Muir, quoted in Linnie Marsh Wolfe (ed.), John of the Mountains: The Unpublished Journals of John Muir, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI, 1979, p. 92. |

| 14 | The narration has been criticised for being ‘overly sanctimonious’, ‘platitudinous and verging on insufferable’, and ‘something even Terrence Malick would have discarded as excessive’; while, in an otherwise glowing response to the film, Schembri suggests that it ought to have been removed altogether. See Todd McCarthy, ‘Telluride Review: River’, Deadline, 5 September 2021, <https://deadline.com/2021/09/river-review-telluride-film-festival-1234827598/>, accessed 10 May 2022; Bradshaw, op. cit.; Dunks, op. cit.; and Schembri, op. cit. |

| 15 | Other films in this vein include Baraka (1992) and Samsara (2011), both shot and directed by Ron Fricke, the cinematographer of the ‘Qatsi’ films; and nature documentaries such as Microcosmos (Claude Nuridsany & Marie Pérennou, 1996), Himalaya (Éric Valli, 1999) and Travelling Birds: An Adventure in Flight (Jacques Perrin, 2001). |

| 16 | For example, the scores for the ‘Qatsi’ films, Baraka and Microcosmos were composed by Philip Glass, Michael Stearns and Bruno Coulais, respectively. |

| 17 | Bill Nichols, Introduction to Documentary, 2nd edn, Indiana University Press, Bloomington & Indianapolis, 2010, p. 162. According to Nichols, other examples of the poetic mode include Rain (Joris Ivens, 1929), Pacific 231 (Jean Mitry, 1949) and The Maelstrom: A Family Chronicle (Péter Forgács, 1997). |

| 18 | The film earned over A$2 million at the box office and sits third overall on the list of highest-grossing Australian documentaries, behind the IMAX films Antarctica (John Weiley, 1991) and Africa’s Elephant Kingdom (Michael Caulfield, 1998). Sherpa sits in seventh place with a gross of A$1.28 million. See ‘All-time Top 10 Australian Documentaries at the Box Office’, Screen Australia, 3 March 2022, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/fact-finders/cinema/australian-films/theatrical-documentaries/top-documentaries>, accessed 10 May 2022. |

| 19 | In their directors’ statement, Peedom and Nizeti suggest that River is part of a ‘planned trilogy of orchestral concert films that explore the impact of landscape on the human heart’. Peedom & Nizeti, ‘Directors’ Statement’, in Madman Entertainment, River press kit, 2021, p. 3. |

| 20 | River dedicates a lengthy sequence to such imagery, which the film’s press kit likens to ‘gorgeous artistic renderings of stands of trees’. Madman Entertainment, ibid., p. 6. |

| 21 | As digital media scholar Francesca Sobande contends, the slogan camouflages structural inequalities in society, while its ‘commodified construction of “we” dismisses the experiences of those who are most at risk and worst affected by COVID-19’. Sobande, ‘“We’re All in This Together”: Commodified Notions of Connection, Care and Community in Brand Responses to COVID-19’, European Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 23, no. 6, 2020, p. 1036. |

| 22 | In her capsule review of the film, Marina Ashioti suggests that the pairing of this music with footage of heterogeneous Indigenous people ‘points towards a historical fixation that the Western world has with “primitivism” – one that fosters a utopian longing for a pre-industrial way of life through a return to nature’. Ashioti, ‘River’, Little White Lies, 17 March 2022, <https://lwlies.com/reviews/river-2/>, accessed 10 May 2022. |

| 23 | Eric Hynes, ‘Where Eagles Dare’, Film Comment, July/August 2018, p. 48. |