In the opening moments of the new Australian documentary Brazen Hussies (Catherine Dwyer, 2020), an on-screen intertitle notes that the women’s movement was ‘reignited’ between 1965 and 1975. That word stuck with me because, while it was most definitely true of that time period, it’s fair to say that the movement has once again reignited in the contemporary age.

While the twenty-four-hour news cycle can allow for the impression that all movements are happening all of the time, social justice is often cyclical, and activism and justice have strong ebbs and flows. Issues that grab public attention inevitably lose their cultural marquee value at one point or another for something else, only to swing back around again when the political winds blow in that direction once more. This phenomenon can be reflected in cinema, too, in which a deluge of titles on a given subject tend to emerge as a response to some (perceived or real) revived interest. For instance, once marriage equality passed into law in the United States, Australia and elsewhere around the world, films on the subject quickly vanished, with queer-activist narratives diverted primarily to transgender-rights issues instead.

But a whiff of those gains being challenged and there is no doubt that cinema will get back into gear. It’s what filmmakers, and in particular documentarians, have been doing for generations.

‘Sexism and the women’s liberation movement’

Brazen Hussies fits neatly into its own trend, one that has been impossible to ignore over the last eighteen months. Film and television works about the feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s have come thick and fast, counting not just two or three but at least a solid dozen. There is the American television miniseries Mrs. America, about efforts to thwart the ratification of the proposed Equal Rights Amendment; and The Glorias (Julie Taymor, 2020), about feminist icon Gloria Steinem – not so coincidentally, also a prominent figure in Mrs. America – who co-founded Ms. magazine, itself the subject of the innovative documentary Yours in Sisterhood (Irene Lusztig, 2018). Further afield, the scheme to disrupt the 1970 Miss World competition in London is the basis for the feature film Misbehaviour (Philippa Lowthorpe, 2020); while the excellent yet long-unavailable documentary Town Bloody Hall (Chris Hegedus & DA Pennebaker, 1979), a recording of a debate between Norman Mailer and feminists Germaine Greer, Jacqueline Ceballos, Jill Johnston and Diana Trilling in 1971, finally received a physical release through boutique DVD label The Criterion Collection in August 2020.

Australia, too, has gotten in on the action. Apart from Brazen Hussies, the 2020 Sydney Film Festival hosted the premiere of Women of Steel (Robynne Murphy), about the battle for workplace equality in Wollongong’s steelworks factories; and I Am Woman (Unjoo Moon, 2019) – a classically tuned biopic of Australian music icon Helen Reddy, whose song of the same name gave a voice to this very movement around the globe – achieved particular prominence.[1]See Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, ‘The Political Is Personal: Helen Reddy and the Generational Politics of I Am Woman’, Metro, no. 204, 2020, pp. 16–21.

The political work on display in Dwyer’s film appears to have often been left out of the larger tale of the feminist movement in favour of overseas figures and milestones.

As suggested by Emma Specter in Vogue, ‘After years of Mad Men–esque filmic reincarnations of a 1950s-era man’s world, it’s only natural that the fight for women’s liberation […] would engender a wave of onscreen representation.’[2]Emma Specter, ‘Why Is 1970s Feminism Having Such a Moment Onscreen?’, Vogue, 29 September 2020, <https://www.vogue.com/article/1970s-feminism-movies>, accessed 12 November 2020. It seems obvious that the recent state of international politics, particularly in the United States, is predominantly to explain for this upswing, something reflected in the appearance of both a documentary and a dramatised feature about the career of late US Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg: RBG (Julie Cohen & Betsy West, 2018) and On the Basis of Sex (Mimi Leder, 2018), respectively. The wider #MeToo movement has also given filmmakers the conviction to tell these stories (as well as financiers and producers the confidence that there is an audience for them).[3]See Jill Serjeant, ‘After Weinstein, #MeToo Themes in Film, TV Reflect Wider Cultural Reckoning’, Reuters, 12 March 2020, <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-people-harvey-weinstein-culture-idUSKBN20Z1AG>, accessed 12 November 2020.

While Brazen Hussies will hopefully not be the last of its kind (it’s impossible to tell the entire story of the local feminist movement in just ninety minutes), it is a documentary that excites as an isolated work – not just for the Australian history it recounts, but also for the possibilities and ideas that it opens up for a new generation of filmmakers.

‘The lunatic fringe’

In telling the story of ‘the women who started a feminist revolution in Australia’,[4]This is the tagline that appears on the film’s poster; see Film Camp, Brazen Hussies press kit, 2020, p. 1. Dwyer has clearly done her research. The first-time filmmaker comes to this project having previously worked on the American documentary She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry (Mary Dore, 2014). Taking initial inspiration from misleading right-wing talking points that pit feminists against women who choose to be stay-at-home mothers, and also from what she felt to be the erasure of her own mother’s generation of activism, Dwyer used the National Library of Australia’s oral-history collections and feminist writings to build a cinematic account of this vital and underrepresented era. Over the course of this research, she encountered books such as Alison Bartlett and Margaret Henderson’s Things That Liberate: An Australian Feminist Wunderkammer, Marilyn Lake’s Getting Equal: The History of Australian Feminism, Anne Summers’ Ducks on the Pond, Zelda D’Aprano’s Zelda and Jean Taylor’s Brazen Hussies: A Herstory of Radical Activism in the Women’s Liberation Movement in Victoria 1970–1979 (the last of which ended up giving Dwyer’s film its wonderfully vulgar title and impetus for being). But when it came to the screen, these stories were hardly anywhere to be found:

I find it strange that there hadn’t yet been a feature documentary about the Australian experience of one of the greatest social and political movements of the 20th century. Though I know that it wasn’t for lack of trying. There is a lost history of social organising, grass-roots activism and widespread personal and political change that is ripe for reviewing now.[5]Catherine Dwyer, ‘Director’s Statement’, in ibid., p. 16.

Whether it be due to a greater push for the telling of women’s stories, or because Australia didn’t have much of an industry capable of doing so at the time the events in question were happening, it seems undeniable that the time it has taken to bring any film like Brazen Hussies to life has only served to ensure its relevance and its necessity. Much like the critical re-evaluation of Reddy’s music that came with the local release of I Am Woman (and again upon her death in September), the political work on display in Dwyer’s film appears to have often been left out of the larger tale of the feminist movement in favour of overseas figures and milestones.

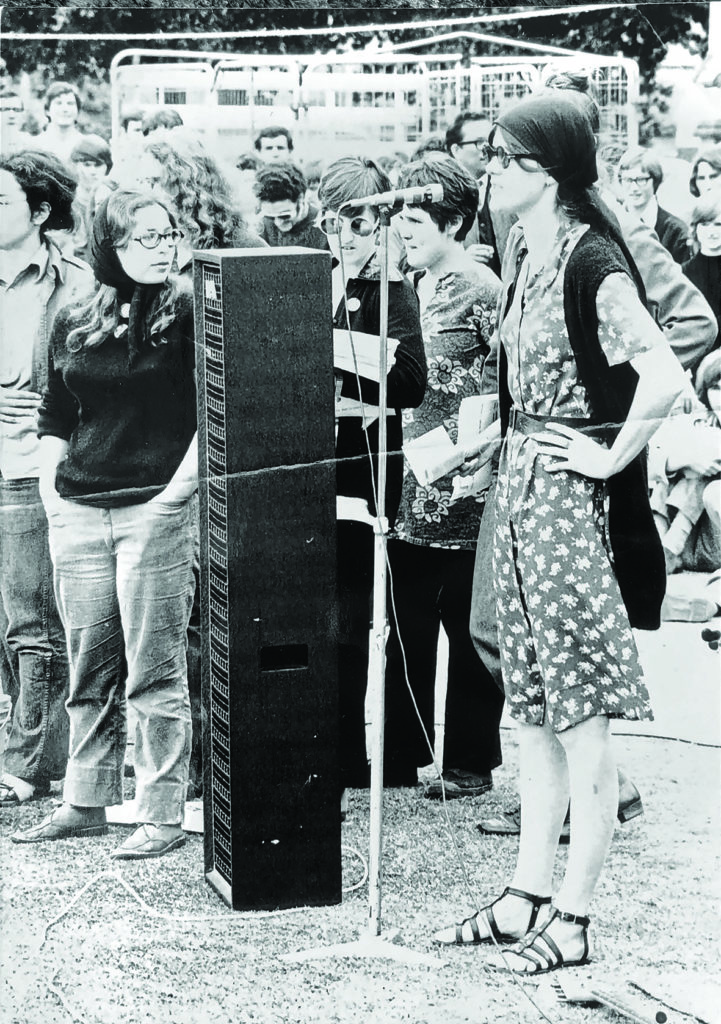

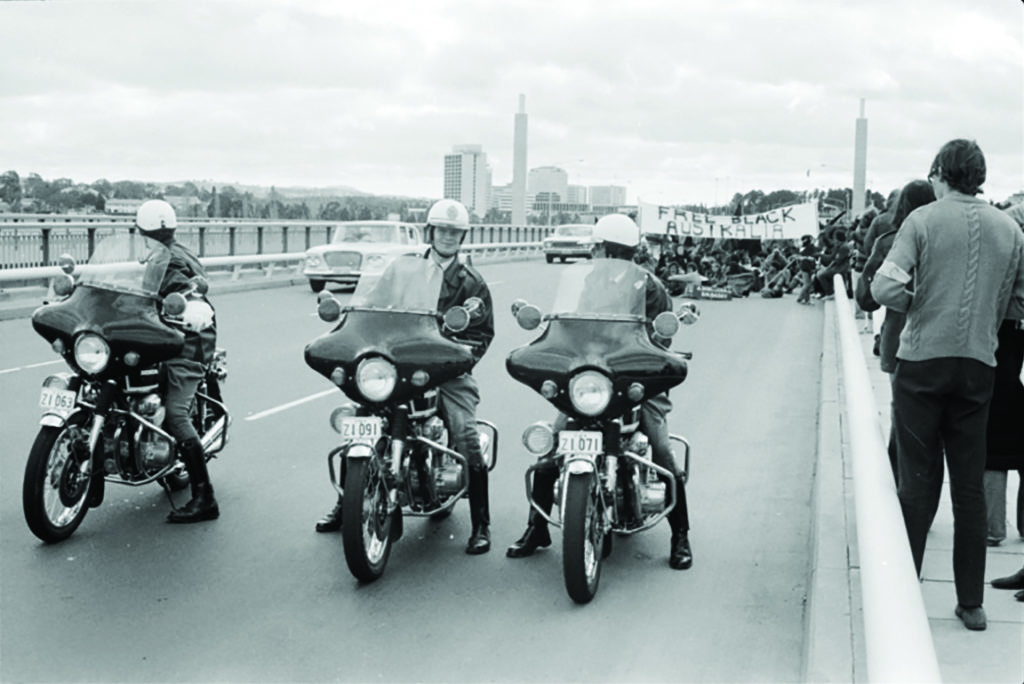

Australians probably shouldn’t, for instance, be more familiar with Ginsburg than Elizabeth Reid, whose appointment to prime minister Gough Whitlam’s team as adviser on women’s affairs (she was nicknamed ‘Supergirl’ in the press) could be the subject of its own eight-part miniseries. Or what about Kate Jennings, who delivered a speech at a 1970 Vietnam War moratorium in which she told the male-dominated activist crowd that ‘it suits you to keep women in the kitchen and in underpaid menial jobs’ because ‘under your veneer, you are brothers to the pig politicians’? Her broadside (which also included the quip, ‘You’ll say I’m a man-hating, bra-burning, lesbian member of the castration-penis-envy brigade – which I am’) ought to be as iconic today as former prime minister Julia Gillard’s famed ‘misogyny’ speech of 2012,[6]See Blair Williams, ‘How Julia Gillard Forever Changed Australian Politics – Especially for Women’, The Conversation, 2 June 2020, <https://theconversation.com/how-julia-gillard-forever-changed-australian-politics-especially-for-women-138528>, accessed 12 November 2020. but isn’t. That may be because of the respective targets, but it perhaps also reflects a wider unwillingness among Australians to critique and scrutinise our political past.

Determining whether this lack of awareness of the Australian women’s liberation movement’s history is a consequence of cultural cringe doesn’t appear to be the film’s goal, although exploring that question would have probably given the finished product a more rounded narrative. As signposted by its opening text, the film’s narrative ends squarely in 1975 as Whitlam is dismissed and his successor, Malcolm Fraser, takes office. Although there are ensuing nods to various contemporary issues via footage from Reclaim the Night, Black/Blak Lives Matter, trans-rights and Pussy Riot–inspired protests, none of these are dug into in any depth; rather, they’re presented before the credits crawl as direct results of the activists’ work featured in the film.

Which they absolutely are, of course. But given Dwyer’s comparative youth, bridging that gap between the generations of feminism could have really underlined the contemporary need for continued action on the cause of women’s rights. As their erosion becomes more blatant, Brazen Hussies could have used its own healthy dose of righteous anger.

The closest the documentary comes to editorialising (deliberately or otherwise) is in its minimisation of Greer, a key figure of the period who is only shown in brief snippets; any discussion of how her brand of feminism dovetailed with the twenty-first century trans-exclusionary ideology that she has come to represent is absent. Likewise, although the intersection of race and gender isn’t ignored entirely – with some attention given to the competing arguments of the Aboriginal women’s movement – I suspect there’s more to say about such dynamics than the film chooses to focus on. Oversights like these are the only elements that somewhat diminish the power of Brazen Hussies’ message.

‘Women’s liberation – how far can it go?’

Impressively, Brazen Hussies features an almost entirely female-fronted production team. The film is produced by Philippa Campey and Andrea Foxworthy and executive produced by Sue Maslin, and its editing, music, sound design and even animation are all solely handled or led by women. While this refreshing nod to industry progressiveness is obviously not any automatic signal of quality, there is a certain verve lent to Brazen Hussies by knowing that so many on its production team are people who have benefited from the actions and sacrifices of its subjects.

As with most documentaries dealing with extensive archival footage, it’s the research and editing teams that are key to the film’s overall success. Editor Rosie Jones – herself an award-winning documentarian, having directed The Family (2016) and its television spin-off, The Cult of The Family (2019)[7]See Felicity Ford, ‘Dark Enlightenment: Crime and Power in The Cult of The Family’, Screen Education, no. 95, 2019, pp. 30–7. – weaves video from campus protests, sharehouse strategy meetings, news reports and much more into something cinematic, and finds some amusing rhythms and beats in her assemblage, too.

The archival dumpster diving has procured some marvellous footage, such as Queensland justice minister Peter Delamothe extolling the virtues of male superiority and future prime minister Bob Hawke in his union days surrounded by female protesters.

The team is also lent wonderful sound bites from its talking-head interviews, whose subjects exude wit and smarts – the likes of which would make them popular in modern-day meme culture if people paid more attention to what they have to say. As Summers, a key member of the early movement, puts it:

If the prime minister is saying, ‘What can I do to make the lives of women better?’ you can’t say, ‘We need orgasms.’ I mean, you can, but we’ve got an opportunity to actually get some practical stuff done, so we had to think, ‘Okay, what in the hell do we really want?’

The archival dumpster diving has procured some marvellous footage, such as Queensland justice minister Peter Delamothe extolling the virtues of male superiority and future prime minister Bob Hawke in his union days surrounded by female protesters. There are dismissive references to 1975’s International Women’s Year as the ‘Year of the Bird’, counterposed with lesbian protesters wholesomely tagging men’s bathrooms with ‘lesbians are lovely’ slogans. While the use of old misogynistic television commercials may be a well-worn trope of these sorts of documentaries, those with a keen eye for Australian film may spot some gems. Among interviews with Margot Nash and Robin Laurie and footage from their underground experimental feminist film We Aim to Please (1973), we also see excerpts from the likes of National Film Board–produced short The Melbourne Wedding Belle (Colin Dean, 1953) and classic documentary Ningla A-Na (Alessandro Cavadini, 1972).

It’s always fun in a documentary like this to pick favourite moments – slivers of history that have been consigned to the archival shelves and yet deserve a spotlight – and imagine an entire film, dramatic or non-fiction, about them. I think of Reid and Jennings, whose careers and achievements ought to hold a more prominent place in our collective understanding of the era. I think of the glimpses of mejane journal, a publication that is absent from the online sphere. I think of the Australian Security Intelligence Organization’s monitoring and surveillance of so-called ‘subversives’. I think of the filmmaking co-ops and the Anarcho Surrealist Insurrectionary Feminist manifesto zine of 1973.

My personal favourite moment, though, may be an excerpt from a 1970s chat show, in which Reddy responds (with more fire than anything mustered by I Am Woman) to a question about whether women’s liberation is a ‘tired old issue’:

Wouldn’t the press like to think so? No. As a matter of fact, about two-and-a-half years ago, Time came out with an editorial saying that the women’s movement was finished as a social issue, and of course the enrolment in various women’s organisations has more than tripled since then. So obviously it’s the press who is dying to see it – particularly the male press is dying to see it – wither on the bow.

As a whole, Brazen Hussies is an accessible, smartly assembled recapitulation of a piece of Australian history that has gone under-acknowledged for too long. As a part of a larger artistic drive to tell the stories of the women’s liberation movement through a contemporary lens, there’s no reason why it should not end up being as valuable to audiences as its larger, more US-focused counterparts.

https://www.brazenhussies.com.au/

Endnotes

| 1 | See Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, ‘The Political Is Personal: Helen Reddy and the Generational Politics of I Am Woman’, Metro, no. 204, 2020, pp. 16–21. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Emma Specter, ‘Why Is 1970s Feminism Having Such a Moment Onscreen?’, Vogue, 29 September 2020, <https://www.vogue.com/article/1970s-feminism-movies>, accessed 12 November 2020. |

| 3 | See Jill Serjeant, ‘After Weinstein, #MeToo Themes in Film, TV Reflect Wider Cultural Reckoning’, Reuters, 12 March 2020, <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-people-harvey-weinstein-culture-idUSKBN20Z1AG>, accessed 12 November 2020. |

| 4 | This is the tagline that appears on the film’s poster; see Film Camp, Brazen Hussies press kit, 2020, p. 1. |

| 5 | Catherine Dwyer, ‘Director’s Statement’, in ibid., p. 16. |

| 6 | See Blair Williams, ‘How Julia Gillard Forever Changed Australian Politics – Especially for Women’, The Conversation, 2 June 2020, <https://theconversation.com/how-julia-gillard-forever-changed-australian-politics-especially-for-women-138528>, accessed 12 November 2020. |

| 7 | See Felicity Ford, ‘Dark Enlightenment: Crime and Power in The Cult of The Family’, Screen Education, no. 95, 2019, pp. 30–7. |