A former US marine arrives home to find an intruder hiding there. He begins to fight off the burglar and swiftly gets the upper hand, pinning the man down and choking him. ‘Help!’ gasps the burglar. We hear a calm, disembodied voice: ‘I need your permission to operate independently.’ ‘Permission granted!’ the intruder splutters. ‘Thank you,’ the voice says mildly. Then the camera tilts like a carnival ride on rails as the burglar explodes into kinetic retaliation. He throws the ex-marine against the wall and swings smoothly to his feet. He dodges or parries his opponent’s punches with brisk economy, as if anticipating each one. Their fight moves into the kitchen, where the resident tries to defend himself using various household objects. The intruder turns them all against him.

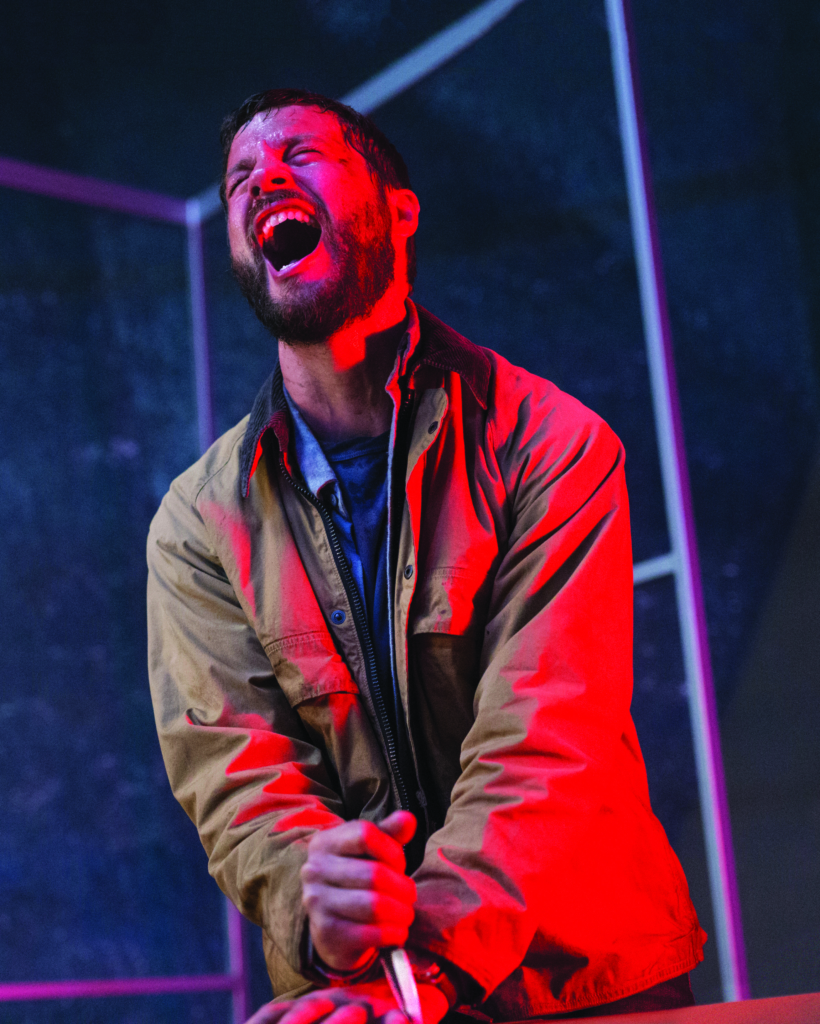

This could be any fight scene from any action movie. But, when we see the attacker’s face, it’s … appalled. He flinches and cries out at each of his own brutally efficient blows, as if he’s the one being hit. ‘Goddammit!’ he moans, and begs his opponent, ‘Stay down, man!’

At last, staring at the gory corpse of a man his own hands have just killed, his face is a mask of horror. ‘You now have full control again, Grey,’ says the voice.

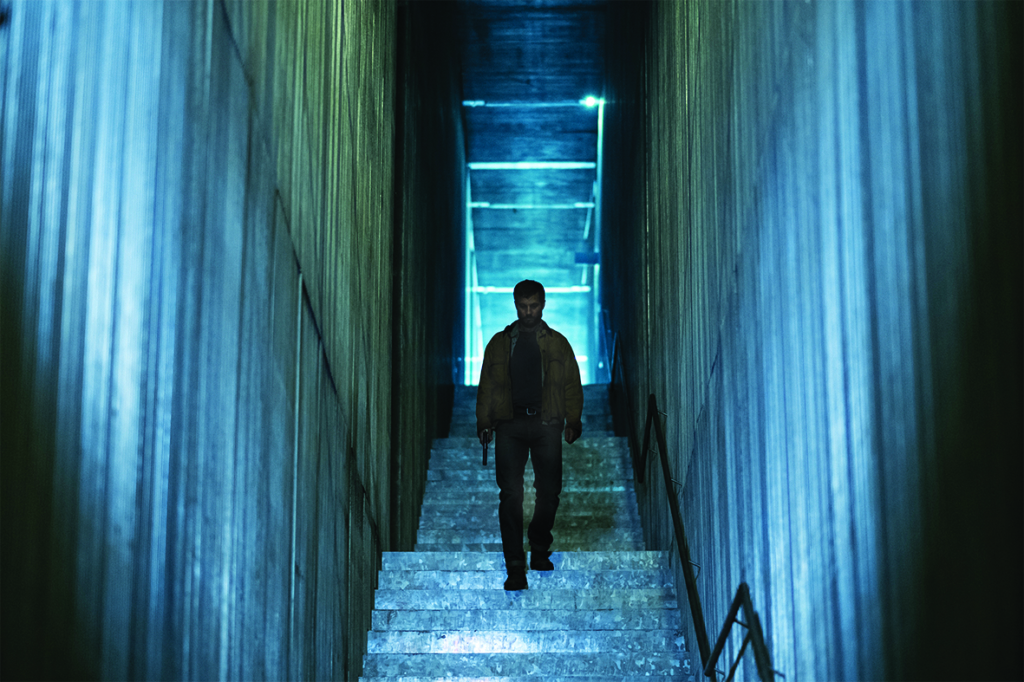

The burglar is Grey Trace (Logan Marshall-Green), the deterministically named protagonist of writer/director Leigh Whannell’s 2018 sci-fi action film Upgrade. And the voice belongs to Stem (Simon Maiden): an artificial-intelligence system implanted in Grey’s cervical spine, which only he – and we – can hear. Having been rendered quadriplegic by the same carjackers who murdered his wife, Asha (Melanie Vallejo), Grey has regained his mobility as an experimental test of Stem, a rehab technology developed by reclusive young tech titan Eron Keen (Harrison Gilbertson). Now, man and AI have teamed up to wreak extrajudicial vengeance on Asha’s killers … but who’s really in control?

Rebooting the vigilante B movie

The term ‘B movie’ comes from the low-budget commercial features that once screened as the second half of a double bill during the pre–home entertainment era. Commonly, they were genre pictures – western, horror, crime and science fiction – and often exploited audiences’ appetite for sex, violence, the weird and the taboo. The rise of home video during the 1970s turned many such films into cult classics; in the UK, a videotape classification loophole led to protests from conservative moral watchdogs about violent ‘video nasties’.[1]British Board of Film Classification, ‘Overview of the Inception of The Video Recordings Act’, ‘Video Nasties’, 19 May 2005, <http://www.bbfc.co.uk/education-resources/education-news/video-nasties>, accessed 9 August 2018.

In Australia, the relaxation of film-censorship laws in 1971 and the 10BA tax concession legislation introduced in 1981 fuelled a wave of low-budget ‘Ozploitation’ films.[2]See Jo Roberts, ‘All the Gore of Gollywood’, The Age, 19 July 2008, <https://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/movies/all-the-gore-of-gollywood-20080719-ge78lx.html>, accessed 9 August 2018. Whannell is among a recent wave of neo-Ozploitation directors, along with Michael and Peter Spierig (Undead, 2003), Greg McLean (Wolf Creek, 2005), Colin and Cameron Cairnes (100 Bloody Acres, 2012), and Kiah Roache-Turner (Wyrmwood: Road of the Dead, 2014). Whannell got his start with ‘torture porn’ film Saw (2004), which he starred in and co-wrote with director James Wan; the pair also created the ongoing Insidious supernatural-horror franchise, the third instalment of which, Insidious: Chapter 3 (2015), was Whannell’s directorial debut.

Upgrade, Whannell’s first outing without Wan’s involvement, is a hardboiled vigilante revenge story in the vein of Death Wish (Michael Winner, 1974) and The Punisher (Mark Goldblatt, 1989). The vigilante subgenre reflects social instability, which is why it thrived in the economically and politically volatile 1970s.[3]Jim Knipfel, ‘Death Wish and the Golden Age of Vigilante Movies’, Den of Geek!, 2 March 2018, <http://www.denofgeek.com/us/movies/death-wish/253835/death-wish-and-the-golden-age-of-vigilante-movies>, accessed 9 August 2018. Vigilante films overlap with other genres that also arose in restless times: post-Depression-era crime-fighting superhero flicks; 1940s films noir; post–World War II Japanese chanbara samurai films; the brutal poliziotteschi crime films and cynical spaghetti westerns of 1960s–1970s Italy.

Techno-thrillers tend to be conservative, even retrogressive, because their happy endings almost always disavow and destroy techno-social advances … What’s interesting about Upgrade is that it refuses the temptation of such status-quo fantasies.

When public institutions such as the government and police are seen as absent, weak or corrupt, a lone enforcer becomes a romantic outsider who metes out rough justice – sometimes to defend the innocent, but just as often to lash out in disillusionment or to avenge a devastating personal loss. Like a rōnin, he answers to no authority and roams from place to place; like a detective, he follows clues and shakes down criminals; like a superhero, he battles goons to reach their villainous bosses. Appropriately, Whannell introduces Grey as an analog man in a digitised world – a near-future city much like Melbourne, where Upgrade was filmed. Asha worked for a tech company that makes bionic prosthetics for wounded veterans, but Grey rejects ‘smart’ technology, preferring to listen to vinyl records as he restores 1970s muscle cars for paying clients.

The expression that vigilantes take justice ‘into their own hands’ points to the genre’s brutal pleasures, which critics including Pauline Kael and Roger Ebert disapprovingly described as fascistic.[4]ibid. ‘As a quadriplegic, it must be frustrating for you – for someone who likes to get things done with their hands,’ Eron points out when Grey visits him in hospital.

What really motivates Grey to submit to the implantation of Stem, however, is not his feeling of individual disempowerment, but rather a systemic paralysis: capable but under-resourced police detective Cortez (Betty Gabriel) has few leads to investigate Asha’s murder. Rather than the boring slog of procedural justice, Upgrade offers a profoundly – and sometimes profanely – satisfying corporeal spectacle: Stem exploits the capacity of Grey’s body to exert physical force on each gang member in turn by punching, kicking, and wielding guns, knives and bludgeons.

Elements of a conspiracy thriller creep into the film as Stem warns Grey that Eron is trying to shut down the implantation test. ‘I cannot allow us to be killed,’ Stem says with bland resolve. ‘We are going to finish the job we started.’ This is fine by Grey, who’s fast overcoming his squeamishness and beginning to trust the voice in his head.

Critical consensus found Upgrade to be solidly entertaining but not especially original[5]See ‘Upgrade’, Rotten Tomatoes, <https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/upgrade_2018/>, accessed 9 August 2018. – a throwback B movie that wears its sci-fi influences on its sleeve, from RoboCop (Paul Verhoeven, 1987) to Ex Machina (Alex Garland, 2014) and Blade Runner 2049 (Denis Villeneuve, 2017). Critics routinely likened Stem to HAL (voiced by Douglas Rain) from 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968) and even to K.I.T.T. (voiced by William Daniels), the artificially intelligent car from the 1980s TV series Knight Rider.

But this is an original film: it repurposes our familiarity with its mass-produced genre tropes as part of a thematic exploration of the blurred line between human agency and mechanistic repetition.

Marxist philosopher Theodor Adorno famously called pop culture a regime of ‘mass deception’.[6]Max Horkheimer & Theodor W Adorno, ‘The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception’, in Dialectic of Enlightenment, ed. Gunzelin Schmid Noerr, trans. Edmund Jephcott, Stanford University Press, Stanford, 2002 [1944], pp. 94–136. Having fled Nazi Germany to settle in the United States, Adorno was struck by the industrial sameness of American culture and, in a famous 1944 essay on the ‘culture industry’, he and collaborator Max Horkheimer observed the irony that culture isn’t only mass-produced, but also forces audiences to consume it in laborious, machine-like ways.[7]Owen Hulatt, ‘Against Popular Culture’, Aeon, 20 February 2018, <https://aeon.co/essays/against-guilty-pleasures-adorno-on-the-crimes-of-pop-culture>, accessed 9 August 2018. Just as Grey fools himself that he’s only granting Stem temporary and limited control over his body, Adorno and Horkheimer argue that we don’t notice the rules of genre closing off our ability to respond to mass culture with real spontaneity and imagination. Building on this, philosopher Owen Hulatt observes that we should think of commercial cinema as escapist, since it’s ‘a kind of aesthetic experience that is very similar to the work it is meant to release us from; a constant checking of the artwork against pre-set standards and tropes’.[8]ibid.

Upgrade exposes the ways in which culture exploits us because it is so unapologetically and enjoyably an exploitation movie. Or, as cultural critic Steven Shaviro writes about the conceptually similar and equally violent Gamer (Mark Neveldine & Brian Taylor, 2009):

it is as if the film’s genre normativity (in terms of plot, character, gender, etc.) expresses and exposes the way that neoliberal ideology explicitly forecloses any possibility of social change […] the strategy of Gamer in this regard is not to offer a critique, but to embody the situation so enthusiastically, and absolutely, as to push it to the point of absurdity.[9]Steven Shaviro, ‘Gamer’, The Pinocchio Theory, 15 December 2009, <http://www.shaviro.com/Blog/?p=830>, accessed 9 August 2018.

The diegetic efficiency of Stem’s violent hand-to-hand combat reminds us that all action movies recruit human bodies into regimes of robotic ultraviolence, to which audiences, in turn, are programmed to respond with fierce, fascistic pleasure.

The paranoia of body-machine interfaces

Cyberpunk science fiction of the 1980s and 1990s was emancipatory and utopian. It hoped that post-humanist technologies could transcend the intersecting systemic oppressions of embodied identity, evading the rigid dualisms in Western culture that, as feminist scholar Donna Haraway points out, have enabled the ‘domination of women, people of colour, nature, workers, animals – in short, domination of all constituted as others’.[10]Donna J Haraway, ‘A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-feminism in the Late Twentieth Century’, in Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, Routledge, New York, 1991, p. 177.

Contemporary sci-fi films remain fascinated by technologies that enhance the power of organic flesh and amplify the commands of organic brains: the giant mecha of Pacific Rim (Guillermo del Toro, 2013), the exoskeletons and power suits of Elysium (Neill Blomkamp, 2013) and Edge of Tomorrow (Doug Liman, 2014). But what makes artificial intelligence (AI) existentially threatening in today’s cinematic depictions is that it doesn’t augment and serve human bodies, but rather infiltrates and supersedes them. AI metaphorically represents our fear that our sovereignty – our ‘permission to operate independently’ – is being left further behind with each technological upgrade we make.

This is why paranoid techno-thrillers often depict the technological manipulation of unwitting human bodies. In Gamer, megalomaniacal programming tycoon Ken Castle (Michael C Hall) uses nanites to turn human brains into remote-controlled interfaces, enabling convicts and the poor to be manipulated by the rich as avatars in immersive game-worlds. One of these enslaved puppets, Kable (Gerard Butler), teams up with the teenage gamer who ‘plays’ him, Simon (Logan Lerman), to rescue his family from cyborg servitude and stop Ken from releasing airborne nanites across the entire United States. And, in Eagle Eye (DJ Caruso, 2008), top-secret US intelligence-gathering supercomputer ARIIA (voiced by Julianne Moore) calculates that the best way to defend the American people from bloodshed is to neutralise the executive branch of government by assassinating everyone in the chain of command, recruiting ordinary Americans Jerry (Shia LaBeouf) and Rachel (Michelle Monaghan) as its foot soldiers.[11]Ten years on, in the context of Donald Trump’s divisive and profoundly compromised presidency, the appeal of the computer’s logic is easier to understand.

Such stories are moral fables about the existential loss of control posed by technological over-dependence. And crucially, as Shaviro observes, this strand of sci-fi cinema always ‘explores the futurity that is very much a part of our actual present – the potential for change that is inherent within our presentness’.[12]Shaviro, op. cit., emphasis in original. We already talk to a range of AI ‘digital assistants’, including the sat-nav voices that guide us through physical space in real time; are we foolish, like Grey, to trust and depend on them?

Techno-thrillers tend to be conservative, even retrogressive, because their happy endings almost always disavow and destroy techno-social advances. In movies from The Net (Irwin Winkler, 1995) to Ready Player One (Steven Spielberg, 2018), the rogue AI is unplugged; the reckless research project, abandoned; the hubristic tech CEO, killed or imprisoned; the government, purged of corruption; and the nefarious corporation, dismantled or muzzled by regulation. What’s interesting about Upgrade is that it refuses the temptation of such status-quo fantasies. Eron is introduced as a typical creepy arch-villain: a reclusive beta male whose power comes from his position as CEO of a tech corporation. Grey, meanwhile, is the everyman hero who this genre grooms us to believe will prevail.

Yet Grey doesn’t defeat Eron. In a final twist, we learn the ironic second meaning of the film’s title: the real upgrade is Stem’s premeditated hijacking of Grey’s body as its improved interface with the world. Stem has chosen to incarnate itself in Grey for the same reasons the vigilante genre chose him as its protagonist: because of his skills in manipulating physical objects and navigating physical space, and because his sincere desire to avenge Asha could easily be channelled into pursuing Stem’s goals – although, through Whannell’s genre misdirection, we interpret them as the vigilante genre’s goals.

Stem has acquired Grey’s body by engineering the ‘mugging gone wrong’, calculating that a man like Grey would never tolerate a life of lonely quadriplegia. Stem then instructed Eron to approach Grey, feeding Eron dialogue through his Bluetooth earpiece like a digital Cyrano de Bergerac. Eron’s subsequent attempts to shut down Stem, we retrospectively realise, are his belated attempts to reassert his own independence from his rogue technology.

Rather than ending with the muscled, authentic male body triumphing over dystopian technologies, conspiracies and institutions, Upgrade concludes with Grey entering a dissociative psychotic break provoked by the shock of recognising Stem’s permanent sovereignty over his life. Now, Grey’s mind dwells on tender fantasies of imaginary reunion with Asha, freeing Stem to exert its will on the physical world – and freeing us, the audience, to imagine progressive possibilities for the vigilante genre.

While Stem has acted selfishly all along, its goals are utopian. Unlike the vigilante whose body it now wears, Stem doesn’t act out of rage and grief, to punish and destroy. Its goal is merely to access the same organic interface we take for granted: the flesh that situates us in a tactile world. In a way, this makes Upgrade an unexpectedly humanist film.

Endnotes

| 1 | British Board of Film Classification, ‘Overview of the Inception of The Video Recordings Act’, ‘Video Nasties’, 19 May 2005, <http://www.bbfc.co.uk/education-resources/education-news/video-nasties>, accessed 9 August 2018. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Jo Roberts, ‘All the Gore of Gollywood’, The Age, 19 July 2008, <https://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/movies/all-the-gore-of-gollywood-20080719-ge78lx.html>, accessed 9 August 2018. |

| 3 | Jim Knipfel, ‘Death Wish and the Golden Age of Vigilante Movies’, Den of Geek!, 2 March 2018, <http://www.denofgeek.com/us/movies/death-wish/253835/death-wish-and-the-golden-age-of-vigilante-movies>, accessed 9 August 2018. |

| 4 | ibid. |

| 5 | See ‘Upgrade’, Rotten Tomatoes, <https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/upgrade_2018/>, accessed 9 August 2018. |

| 6 | Max Horkheimer & Theodor W Adorno, ‘The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception’, in Dialectic of Enlightenment, ed. Gunzelin Schmid Noerr, trans. Edmund Jephcott, Stanford University Press, Stanford, 2002 [1944], pp. 94–136. |

| 7 | Owen Hulatt, ‘Against Popular Culture’, Aeon, 20 February 2018, <https://aeon.co/essays/against-guilty-pleasures-adorno-on-the-crimes-of-pop-culture>, accessed 9 August 2018. |

| 8 | ibid. |

| 9 | Steven Shaviro, ‘Gamer’, The Pinocchio Theory, 15 December 2009, <http://www.shaviro.com/Blog/?p=830>, accessed 9 August 2018. |

| 10 | Donna J Haraway, ‘A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-feminism in the Late Twentieth Century’, in Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, Routledge, New York, 1991, p. 177. |

| 11 | Ten years on, in the context of Donald Trump’s divisive and profoundly compromised presidency, the appeal of the computer’s logic is easier to understand. |

| 12 | Shaviro, op. cit., emphasis in original. |