Listen to Bangarra Dance Theatre’s artistic director, Stephen Page, speak about the First Nations–led company he has led for thirty years, and it’s clear the fire still burns inside him. It’s all in the name, really. Bangarra is the Wiradjuri word meaning ‘to make fire’. That light radiating from Stephen captivated documentary filmmaker Nel Minchin when she saw him speak about his mesmeric dance film Spear (2015) at a Sydney Theatre Company (STC) event in 2016. She recalls:

I saw him speak and just realised what an interesting character he is. Spear is such a visceral and beautiful film, and a really interesting story he explores without a dialogue-based script. And I thought, ‘I want to find out more about that story and that person.’

Minchin grew up in Perth and was aware of the award-winning work of Bangarra, but not intimately so. She has a track record in telling stories about theatrical companies, however. Her debut feature, Matilda & Me (co-directed by Rhian Skirving, 2016) navigated the wild success of her comedian, singer and composer brother Tim’s musical adaptation of the titular Roald Dahl novel. Indeed, she was working with STC on another movie-to-musical documentary – Making Muriel (2017), chronicling the stage adaptation of the film Muriel’s Wedding (PJ Hogan, 1994) – when she happened to hear Stephen speak about Spear.

According to Minchin, Stephen thought she was ‘quite ballsy’ in approaching him for permission to explore his story. That was the spark that became the celebratory documentary Firestarter: The Story of Bangarra (2020), and co-director Wayne Blair joined the embryonic project shortly thereafter. As Minchin sees it, her role was as the outsider looking in: she brought documentary skills with a theatrical focus, whereas Blair was the insider with an intimate knowledge of Bangarra and of the three Page brothers at its heart – Stephen, Russell and David. He also understood, inherently, the political struggles of this country’s First Nations peoples. While this is Blair’s first documentary, he has an extensive directing career in film (2012’s The Sapphires and 2019’s Top End Wedding) and television (including Redfern Now and the second season of Mystery Road). ‘He is a much more experienced filmmaker,’ Minchin says. ‘I certainly learned a lot.’ She adds:

Wayne is part of this generation who kind of grew up together through the nineties and 2000s [and] who have created such an impact on the arts scene, in terms of Indigenous storytelling and breaking boundaries, over and over again.

Sadly, Blair was unavailable to speak about the film with Minchin, having been caught up with filming the second season of Total Control for the ABC. I raise with Minchin that I’m very conscious that this means a white film journalist is speaking to the film’s white co-director. ‘When Wayne and I are talking together, it feels really comfortable,’ Minchin says, agreeing that it’s a more delicate situation to navigate without him. ‘Wayne and I worked very, very closely together. So we always had this lovely collaboration and tension in a good way, of the outsider and insider perspective to this story.’

She relished their working relationship, and the depth their different perspectives brought to the project. ‘No creative collaboration is going to be totally smooth sailing,’ Minchin notes, ‘We would have conversations that were pretty robust, but ultimately respected each other’s opinions and heard them.’

Listening is important. They conducted most interviews together, playing to each other’s strengths. Minchin, who describes herself as something of a history nerd, also relished the challenge of delving deep into Bangarra’s archive, which contained some 1000 videos. ‘It was a beautiful research project, but it was a lot, a lot, a lot,’ she says.

The process was made somewhat easier by the extensive work carried out in house by Bangarra. The company engaged former dancer Yolande Brown, who performed with them for sixteen years, to tackle the two-year task of digitising their wealth of archival material in the lead-up to their thirtieth-anniversary celebrations in 2019. The vaults included television interviews, photographs, costume and set design, music, and language work, tracing three decades’ worth of creativity. This digital record, dubbed Knowledge Ground, was presented in an exhibition of the same name hosted at Carriageworks in Sydney, and also lives on for all to access on the Bangarra website.[1]See Bangarra Dance Theatre Knowledge Ground website, <https://bangarra-knowledgeground.com.au/>, accessed 19 February 2021. As Brown put it to ABC News regarding the wealth contained there, ‘What you see on [the theatre] stage is just the tip of the iceberg.’[2]Yolande Brown, quoted in Teresa Tan ‘Bangarra Dance Theatre Marks 30 Years with Digital Archive and Exhibition’, ABC News, 13 December 2019, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-12-13/knowledge-ground-bangarra-dance-theatre-digital-archive/11785840>, accessed 21 February 2021.

‘Wouldn’t it be great if we could all have that time to sit and listen? Because we’d actually start understanding so much more.’

Nel minchin

If Minchin wasn’t submerged in the history of Bangarra beforehand, she certainly is now. ‘I said to Stephen, “I think I’m your biggest stalker.” I mean, I honestly feel like I’ve seen and heard every single interview with him.’ All up, the film took nearly four years to make. ‘My daughter is almost three, and I wasn’t even pregnant with her when it started,’ Minchin says.

Fuzzy handheld footage of the three Page brothers in their youth in Brisbane glows. Their all-singing-and-dancing childhood saw their sisters dress them in drag, and the video camera was always rolling. David’s youthful talent for singing led him to being signed to Atlantic Records, and going on to appear as a guest star on The Paul Hogan Show in 1975. In archival footage, he laughs when saying that his voice breaking was the end of all that. Descending on Sydney in the late 1980s in rapid succession, the trio embedded themselves with like minds and living culture at the National Aboriginal Islander Skills Development Association Dance College (NAISDA).

Their brotherly banter is a joy to behold. Interviewed for the film, former Sydney Festival artistic director Wesley Enoch says that, together, they were like a story from the Dreaming:

Stephen, the kind of responsible one; […] David, with the mischievous kind of twinkle in his eye; and Russell was kind of the mercurial, physical one. Everything was about his body, about his spirit. He would hug the hardest.

South African–born Bangarra co-founder Cheryl Stone speaks about her determination to recruit a then-25-year-old Stephen as Bangarra’s second artistic director, a role initially held by African-American choreographer Raymond Robinson Sawyer. It was felt it was important that an Indigenous Australian lead the company, which had broken away from NAISDA in 1989. ‘Stephen was very inspiring,’ she says. ‘There was a spark for action, theatre, dance.’ Stone felt sure he would bring David and Russell across with him. ‘If I got any one of them, the two would follow.’

It takes a village to build a company as successful internationally as Bangarra. Firestarter pays fitting tribute to Stone and co-founders Carole Y Johnson and Rob Bryant, along with other key figures, including dancer–turned–associate artistic director Frances Rings. But the Pages were its beating heart. This makes the double tragedy of choreographer and dancer Russell’s suicide in 2002[3]‘Bangarra Dancer Russell Page Dies’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 16 July 2002, <https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/art-and-desgn/bangarra-dancer-russell-page-dies-20020716-gdfgdn.html>, accessed 21 February 2021. and music director David’s passing in 2016[4]Linda Morris, ‘Bangarra Dance Theatre Shattered by Death of Composer David Page’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 April 2016, <https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/dance/bangarra-dance-theatre-shattered-by-death-of-composer-david-page-20160429-goi4tn.html>, accessed 21 February 2021. all the more unbearable. An archival clip of presenter Andrew Denton interviewing Stephen about Russell’s death is devastating, as is a new interview with Russell’s now-adult son Rhimi Johnson-Page, who was only twelve when his father passed away. Rings’ anguish over the tragedies is also hard to witness, and so too in a different way is the quiet stoicism of Yolngu songman Djakapurra Munyarryun, another key collaborator.

Art curator and writer Hetti Perkins speaks passionately about the effects of intergenerational trauma on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Firestarter carefully weaves the incredible achievements of Bangarra through the ongoing fallout of this country’s violent colonial past and refusal to reckon with it, consequences that are depicted in Spear. As Stephen told NITV when that film was released,

We were posing and asking ourselves what is it to be a man in the 21st century, what is men’s business in an urban environment, what is male Indigenous testosterone in this male western world. What are our values and cultural custom practices, how do we have one foot in the modern world and another foot in the traditional world. What is our role as a man for our community?[5]Stephen Page, quoted in Nakari Thorpe, ‘Stephen Page’s Spear Gets to the Heart of What It Means to Be a Man,’ NITV News, 10 March 2016, <https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/nitv-news/article/2016/03/10/stephen-pages-spear-gets-heart-what-it-means-be-man>, accessed 25 February 2021.

These ideas swirl around Firestarter. As Minchin says of their generous interviewees reopening these old wounds, ‘It had to be a story about the Page family, but […] it’s a much bigger conversation’ – one that she hopes we can get better at having.

Wouldn’t it be great if we could all have that time to sit and listen? Because we’d actually start understanding so much more […] To be able to have that kind of rigorous chat about this stuff is really important.

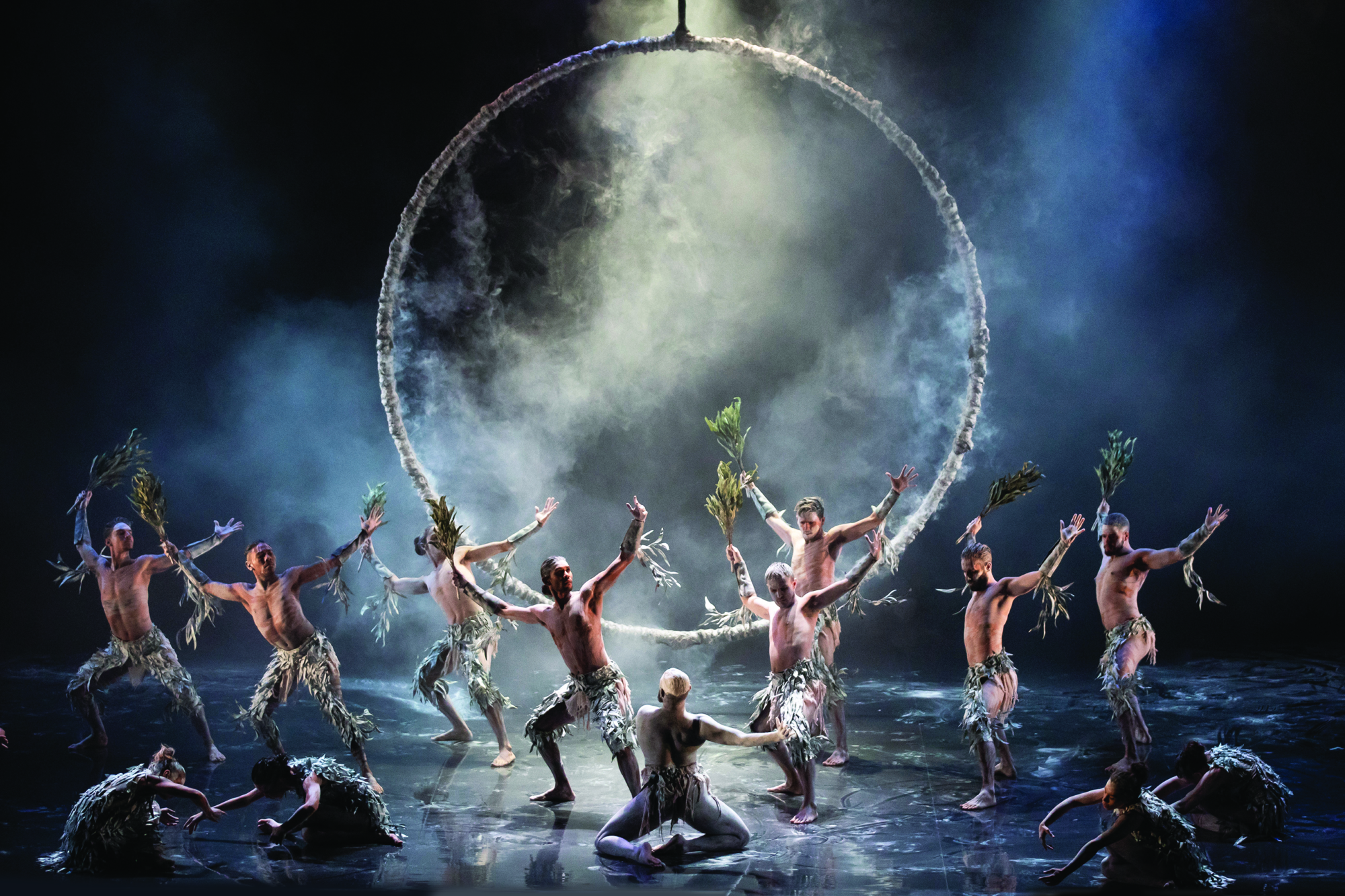

Firestarter is an important film, placing Bangarra as a leader in this way. There is archival footage from 1992 showing the company at Redfern Park, where they performed before then–prime minister Paul Keating made his historic speech. Stephen notes that Keating told him it would be an important day, but says he had no idea at the time just how important. The documentary also draws on behind-the-scenes documentary Making the Awakening, which details the huge efforts that went into Stephen’s unforgettable First Nations–led contribution to the opening ceremony of the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games. Minchin talked her way into the University of New South Wales library to watch the latter on VHS. ‘So there was a bit of a treasure hunt as well,’ she says. Michelle Mahrer’s 1999 documentary Urban Clan was also invaluable, elucidating David’s thinking on fusing contemporary music with traditional language – an electric signature of Bangarra’s breathtaking performances, including the opera-like box-office record-breaker Bennelong.

Russell lives on in the liquid-gold movement of bodies that Stephen continues to sculpt with on stage today, and David is there in the music now crafted by Steve Francis. As Stephen once told me for an article in The Age about Bangarra’s thirtieth-anniversary celebrations,

I just love carrying their legacy […] I watch the dancers and I see Russell’s physical language, and David made the sounds of the wet season sing. He made the land, the sky and the ocean all have a three-way conversation. I was lucky enough to collect those soundscapes when we started to go from analogue to digital. There’s so much greatness in there that I am trying to protect.[6]Stephen Page, quoted in Stephen A Russell, ‘Bangarra Director Frustrated at Slow Pace of Indigenous Politics’, 28 August 2019 <https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/dance/bangarra-s-fire-still-burns-20190828-p52llu.html>, accessed 21 February 2021.

Firestarter thrums with these elements. They were never more alive for Minchin than when she and Blair travelled to Yirrkala, in north-eastern Arnhem Land, where Munyarryun and the Page brothers spent so much time together. She recalls:

We interviewed Djakapurra out on the river. I’d never been up there. I hadn’t seen culture living and breathing quite like it does there. And that was a real moment of thinking, for me, ‘What have we done, as a nation, you know, not respecting this culture for what it is and what it can offer?’

Watching Firestarter, I am reminded of the recent Adam Goodes–focused documentary The Australian Dream (2019), written by First Nations broadcaster Stan Grant and directed by English filmmaker Daniel Gordon, who is white.[7]See Travis Johnson, ‘A Race to the Goal: Adam Goodes’ Story in The Final Quarter and the Australian Dream‘, Metro, no. 203, 2020, pp. 76-83. Both films ask us to look again at our country through the prism of the burdens carried by our heroes (be they dancers or footy players). They ask us to think again about who we are and who we want to be.

Endnotes

| 1 | See Bangarra Dance Theatre Knowledge Ground website, <https://bangarra-knowledgeground.com.au/>, accessed 19 February 2021. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Yolande Brown, quoted in Teresa Tan ‘Bangarra Dance Theatre Marks 30 Years with Digital Archive and Exhibition’, ABC News, 13 December 2019, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-12-13/knowledge-ground-bangarra-dance-theatre-digital-archive/11785840>, accessed 21 February 2021. |

| 3 | ‘Bangarra Dancer Russell Page Dies’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 16 July 2002, <https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/art-and-desgn/bangarra-dancer-russell-page-dies-20020716-gdfgdn.html>, accessed 21 February 2021. |

| 4 | Linda Morris, ‘Bangarra Dance Theatre Shattered by Death of Composer David Page’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 April 2016, <https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/dance/bangarra-dance-theatre-shattered-by-death-of-composer-david-page-20160429-goi4tn.html>, accessed 21 February 2021. |

| 5 | Stephen Page, quoted in Nakari Thorpe, ‘Stephen Page’s Spear Gets to the Heart of What It Means to Be a Man,’ NITV News, 10 March 2016, <https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/nitv-news/article/2016/03/10/stephen-pages-spear-gets-heart-what-it-means-be-man>, accessed 25 February 2021. |

| 6 | Stephen Page, quoted in Stephen A Russell, ‘Bangarra Director Frustrated at Slow Pace of Indigenous Politics’, 28 August 2019 <https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/dance/bangarra-s-fire-still-burns-20190828-p52llu.html>, accessed 21 February 2021. |

| 7 | See Travis Johnson, ‘A Race to the Goal: Adam Goodes’ Story in The Final Quarter and the Australian Dream‘, Metro, no. 203, 2020, pp. 76-83. |