It’s not a big surprise that a film like Reflections in the Dust (Luke Sullivan, 2018) might court controversy. In an era of monolithic mega-blockbusters, a micro-budget slice of arthouse Australiana demands some kind of hook to pierce the bubble of cinematic complacency. So why not promise scandal? Suggest a whiff of something illicit, something beyond the realms of polite society?

Anyway, it worked on me. When an email from distributor The Backlot Films arrived in my inbox offering something ‘too extreme’[1]Email received from The Backlot Films dated 19 February 2019. for audiences, how could an aficionado of fringe cinema deny the call? The full quote – which has been reproduced in various synopses of the film online – is as follows:

The Australian government deemed the film was too extreme for audiences and strongly suggested it not be completed during production, however director Luke Sullivan pushed on with the film, asserting that such an extreme story needs to be told in an era where ‘we are losing grandmothers, mothers, sisters and friends to senseless acts of violence perpetrated by men’.[2]See, for example, Reflections in the Dust’s page on Rotten Tomatoes, <https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/reflections_in_the_dust>, accessed 22 May 2019.

I couldn’t deny the allure. I quickly requested a screener, won over by the promise of not just extreme cinema, but something purposeful, political. Confronting. And, while I can’t speak to the veracity of the synopsis’s assertion of behind-the-scenes controversy – the film remains proudly in place on the Screen Australia website,[3]It is idly interesting to note the differences between the synopsis I received via email (which was subsequently reproduced on the aforementioned websites) and the corresponding synopsis used by Screen Australia. The latter eschews the word ‘extreme’ and avoids any allusions to funding controversies; see ‘Reflections in the Dust’, The Screen Guide, Screen Australia website, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/the-screen-guide/t/reflections-in-the-dust-2019/36917/>, accessed 22 May 2019. a fact that seems to controvert such claims, but I’ll avoid dabbling in backyard investigative journalism – there’s no denying that Reflections in the Dust is a distinctive cinematic artefact.

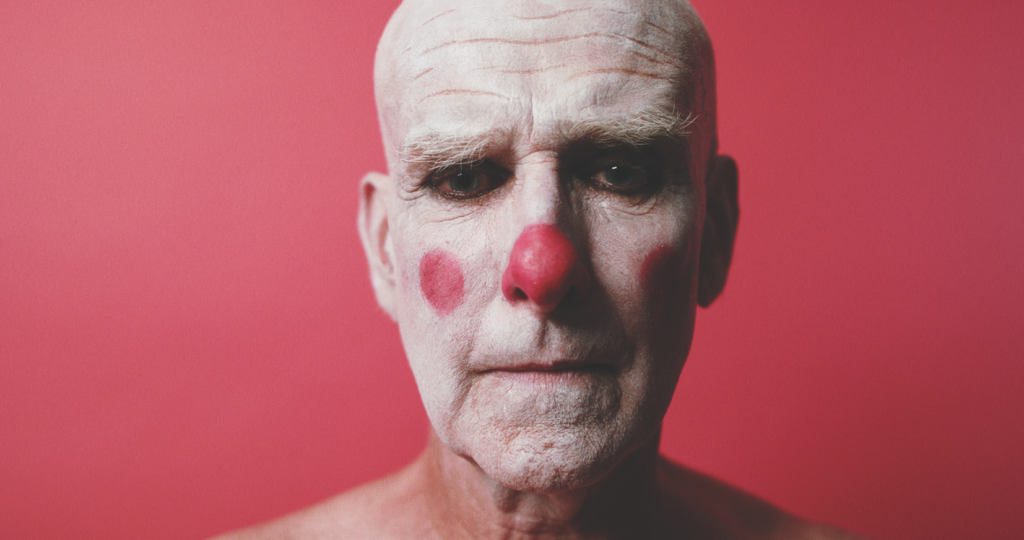

Sullivan’s second feature film – following 2016’s You’re Not Thinking Straight – is a misshapen thing: crude and compelling, forceful and frustrating. If we disregard the context offered by the distributor’s synopsis, we’re left with a spare portrait of a toxically co-dependent relationship between an unnamed father (Robin Royce Queree, credited as ‘The Clown’ for the greasepaint make-up perpetually smeared on the character’s face) and his daughter, ‘Freckles’ (Sarah Houbolt). With a slender running time of seventy-five minutes, narrative coherence is avoided in favour of direct, evocative dialogue. The father and daughter interact – with each other, and with occasional outsiders (Aldo Fedato, Sage Godrei) – in the waterlogged wilderness of the Australian outback. They reminisce about days past and jostle for superiority in their relationship, with the looming threat of violence ever present.

Reflections in the Dust wasn’t quite the film I’d expected from its attention-grabbing publicity material … It’s certainly hard to imagine Screen Australia bureaucrats pulling out their hair in reaction to a film that could be described as mid-twentieth-century European arthouse meets film-student experimentation.

Rarely does the camera stray far from the actors’ faces. Director of photography Ryan Barry-Cotter shoots almost exclusively in close-ups (with the occasional mid shot), creating an intense intimacy with the characters. While we’re in the wilderness, Sullivan and Barry-Cotter opt for stark black-and-white cinematography; these scenes are often interspersed with vibrantly colourful talking-heads shots, as Queree and Houbolt address the camera against bright backdrops (his, red; hers, blue).

In any case, Reflections in the Dust wasn’t quite the film I’d expected from its attention-grabbing publicity material. While I’ll grant that its relentless intensity makes it a somewhat confronting experience, the ‘extreme’ descriptor strikes me as, well, a touch extreme. It’s certainly hard to imagine Screen Australia bureaucrats pulling out their hair in reaction to a film that could be described as mid-twentieth-century European arthouse[4]Reinforced by the repeated appearance of Christian iconography – all the shots of baptisms, crosses and crucifixes recall Luis Buñuel’s affinity for Christian symbols. meets film-student experimentation (only with entirely more Australian accents than you’d expect from either). The film is undeniably memorable – it’s more interesting than many of the swiftly forgotten exemplars of middlebrow Australian cinema passing themselves off as high art, certainly, if lacking in a certain punch. But I was expecting something purposeful – and Reflections in the Dust, as it turns out, primarily suffers from a lack of clear purpose despite its confidently worded synopses.

Proximity

The close-ups that dominate Reflections in the Dust’s cinematography aren’t arbitrary. They’re simpatico with Sullivan’s desire to challenge the viewer, something he’s been explicit about in interviews; speaking to FilmInk last year, for instance, he said that his ‘aim as a director has always been to push audiences to the limit and get under their skin’.[5]Luke Sullivan, quoted in Dov Kornits & Travis Johnson, ‘Luke Sullivan and Sarah Houbolt: Reflecting on Reflections in the Dust’, FilmInk, 25 July 2018, <https://www.filmink.com.au/luke-sullivan-sarah-houbolt-reflecting-reflections-dust/>, accessed 22 May 2019.

This proximity to the characters is largely absent of context, however, which is what pushed me to the limit watching the film. Other than the father–daughter relationship, very little is explained or implied to the audience regarding the emotional, social and even geographic realities facing Freckles and her father. Where does the film take place? How long have these two been out here – wherever ‘here’ is – away from civilisation? Who are the people that seem to exist on the margins of the central duo’s camp site, intermittently interacting with them? What is the purpose of the coloured confessional interludes?

Some of these questions are answered – and dutifully regurgitated in most reviews I’ve read – in the film’s publicity material: ‘An unspoken event has caused civilization to crumble, leaving the survivors to cluster in the wilderness.’[6]‘Reflections in the Dust’, The Backlot Films website, <https://www.thebacklotfilms.com/works/reflections-in-the-dust>, accessed 22 May 2019. I’ve watched the film twice and, while I found the setting haunting, honestly, I wouldn’t have picked it as post-apocalyptic without such assistance from the filmmakers (if anything, I would’ve guessed that the psychologically unstable father had absconded to the outback à la Debra Granik’s 2018 film Leave No Trace). Similarly, it wasn’t clear that the aforementioned confessionals are documentary-style conversations with the actors, rather than the characters they’re playing, until I encountered Sullivan saying as much in an interview with Film in Revolt.[7]See David Paicu, ‘Interview with Luke Sullivan / Refections [sic] in the Dust’, Film in Revolt, 13 March 2019, <https://www.filminrevolt.org/interview-with-luke-sullivan-refections-in-the-dust/>, accessed 22 May 2019.

While I don’t necessarily expect Reflections in the Dust to provide a realistic background or setting … I do think that it suffers from the absence of an emotional reality with which to engage its audience.

It’s important to emphasise that what I’m critiquing isn’t the surrealistic setting. Indeed, the film’s distinctive surrealist qualities are its best features, and demonstrative of the director’s talent. In that Film in Revolt piece, he asserts:

I saw a story like this potentially being a bit too realistic and that it could become too unoriginal and dull in a sense. In order for people to connect to it I had to approach it from a completely different aspect.[8]Luke Sullivan, quoted in Paicu, ibid.

While I don’t necessarily expect Reflections in the Dust to provide a realistic background or setting, given its experimentative approach, I do think that it suffers from the absence of an emotional reality with which to engage its audience. Despite all its close-up camerawork, the film leaves a distance between its characters and viewers. This is further exacerbated by the affected costuming; in addition to The Clown’s make-up, Freckles is often clad in a vintage wedding dress, while their erstwhile visitors have their own masquerade-esque looks. As committed as the actors are – and Queree and Houbolt certainly hold nothing back – the lack of empathetic grounding for their situation keeps us at arm’s length. And that’s only reinforced by the awkward (deliberately so, I presume) confessional scenes, which remind us of the separation between performer and character.

Generously, you can read this as Sullivan’s attempt to create a Brechtian chasm between his players and his audience,[9]For more on theatre-maker Bertolt Brecht’s ideas on the separation of audience from work, see ‘Alienation Effect’, Encyclopædia Britannica, <https://www.britannica.com/art/alienation-effect>, accessed 22 May 2019. underlining the artificiality of the exercise through a carefully developed surrealistic environment. Maybe. But that flies in the face of Sullivan’s earlier quote about wanting to ‘get under [his audience’s] skin’ and the synopsis’s emphasis on the film’s ‘extreme’ nature. Reflections in the Dust is left to compel or confront its audience aesthetically and perhaps academically, but, despite desperately striving for emotional affect, its overall effect is numbing.

Purpose

Reflections in the Dust’s publicity material proudly proclaims that it’s a ‘powerful allegory for the epidemic of violence against women in Australia’.[10]‘Reflections in the Dust’, The Backlot Films website, op. cit. That statement is implicitly linked to the aforementioned controversy, and I can understand why a film tackling such a contentious issue might come off as polemical. Depicting violence against women – and, particularly, domestic violence – without toppling over into exploitation is tricky. A couple of years ago, I praised Ben Young’s Hounds of Love (2016) for its insights into the psychology of domestic violence,[11]Dave Crewe, ‘Lady Killers: Hounds of Love, Horror and Violence Against Women’, Metro, no. 193, 2017, pp. 12–7. but the film was just as readily – and reasonably – attacked by critics for being misogynistic or otherwise problematic.[12]See, for example, MaryAnn Johanson, ‘Hounds of Love Movie Review: Serial-killer Porn’, Flick Filosopher, 27 July 2017, <https://www.flickfilosopher.com/2017/07/hounds-love-movie-review-serial-killer-porn.html>, accessed 22 May 2019.

That comparison isn’t arbitrary; Sullivan has identified ‘early 2000s horror movies’ as formative influences on his filmmaking: ‘the Texas Chainsaw Massacre remake [Marcus Nispel] from 2003 […] Hostel [Eli Roth, 2005] – that crazy torture horror movie – and Wolf Creek [Greg McLean, 2005]’.[13]Sullivan, quoted in Paicu, op. cit. It’s instructive to compare films from this genre, which are often pilloried for their depictions of violence, particularly against women, to Reflections in the Dust. While Sullivan’s film avoids explicit on-screen violence until its final minutes, when The Clown (non-lethally) drowns his daughter in a flooded lake, it operates similarly to many horror films in the way it builds dread through the development of a toxic relationship. But, whereas a conventional horror film might be content evoking an emotional response from its audience – as discussed, an area in which Reflections in the Dust falls down – this is a film positioning itself as, again, a ‘powerful allegory’. That promises that its vision of suffering will be driven by a deeper message (in this case, regarding violence against women).

I’ll be honest: if the film is intended as an allegory, I’m not precisely sure what it’s an allegory for. It’s a representation of domestic abuse, certainly; Queree’s character, who’s mentally ill (critic Alexandra Heller-Nicholas identifies him as having schizophrenia,[14]Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, ‘Reflections in the Dust’, Alliance of Women Film Journalists, 21 February 2019, <https://awfj.org/blog/2019/02/21/reflections-in-the-dust-review-by-alexandra-heller-nicholas/>, accessed 22 May 2019. a reading supported by the film’s synopsis), subjects his daughter to emotional, verbal and physical aggression, perpetuating a demoralising cycle of berating and gaslighting. There’s also the suggestion of sexual abuse, reinforced by the sexually charged confessional conversations, but this remains implicit.

While Reflections in the Dust is a chilling representation of an abusive domestic situation, I’m not convinced that it transcends the bounds of representation to proffer a meaningful commentary on domestic violence. This isn’t necessarily a problem in and of itself. Films aren’t required to be more than what they are; a sophisticated, surrealistic depiction of toxic masculinity – which this is, despite my quibbles about its lack of emotional nuance! – is a worthy project. And perhaps it’s unfair to judge Sullivan’s work by its overreaching publicity material.

I think the film’s failure to meaningfully articulate how domestic violence operates – the power dynamics, the influence of mental illness, the textures of co-dependency – or extrapolate from its central couple’s situation to a broader societal issue speaks to why it ultimately underwhelmed me. Sullivan’s attempts to justify his work’s allegorical underpinnings in interviews fall back on statistics about men’s violence against women in Australia. These are disturbing, yes, and I would agree with Sullivan’s claim that this situation is becoming a ‘national emergency [and] Australia needs to become a safer place for women’.[15]Luke Sullivan, quoted in Matthew Eeles, ‘Interview: Luke Sullivan’, Cinema Australia, 14 October 2018, <https://cinemaaustralia.com.au/2018/10/14/interview-luke-sullivan/>, accessed 22 May 2019. But these concerns are largely disconnected from the film’s very specific setting and story.

Disconnection is really at the heart of Reflections in the Dust’s problems. As much as I’ve focused on what doesn’t work about the film, it’s important to acknowledge its successful components: the setting and the central relationship. These might be immiscible elements – the denatured, decontextualised outback obviating Sullivan’s attempts to offer social commentary regarding abusive relationships as that very relationship draws attention away from said setting – but each is individually potent. The setting, in particular, lingers in the memory long after seeing the film; something about its ambiguous incompleteness leaves one’s brain striving to fill in the gaps, to populate its arcane dreamscape.

The father–daughter relationship, meanwhile, lives or dies on its actors’ performances. While the sense of place, the filmmaking and pretty much every stylistic choice repels the audience from these characters, there’s a core of authenticity – thanks in large part to Queree and Houboult – that resonates even as thematic analysis falters. Even if Sullivan’s film ultimately disappointed me, there’s something enigmatic, something magnetic, about it.

Reflections in the Dust may not quite be the film that its publicity team’s email promised. It’s not controversial, nor especially extreme, and it fails to make its case as an allegory. It’s hard to hold that against the film proper, even as its publicity has shaped its critical conversation. But, while its director might stretch his intentions a tad (as young directors[16]Sullivan was twenty-three years old at the time of the film’s release; see Eeles, ibid. are wont to do), his ambition and originality are undeniable. This might not be the film it wants to be, but it does show real promise for Sullivan’s nascent filmmaking career – if he can avoid real controversy in the future.

https://www.thebacklotfilms.com/works/reflections-in-the-dust

Endnotes

| 1 | Email received from The Backlot Films dated 19 February 2019. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See, for example, Reflections in the Dust’s page on Rotten Tomatoes, <https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/reflections_in_the_dust>, accessed 22 May 2019. |

| 3 | It is idly interesting to note the differences between the synopsis I received via email (which was subsequently reproduced on the aforementioned websites) and the corresponding synopsis used by Screen Australia. The latter eschews the word ‘extreme’ and avoids any allusions to funding controversies; see ‘Reflections in the Dust’, The Screen Guide, Screen Australia website, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/the-screen-guide/t/reflections-in-the-dust-2019/36917/>, accessed 22 May 2019. |

| 4 | Reinforced by the repeated appearance of Christian iconography – all the shots of baptisms, crosses and crucifixes recall Luis Buñuel’s affinity for Christian symbols. |

| 5 | Luke Sullivan, quoted in Dov Kornits & Travis Johnson, ‘Luke Sullivan and Sarah Houbolt: Reflecting on Reflections in the Dust’, FilmInk, 25 July 2018, <https://www.filmink.com.au/luke-sullivan-sarah-houbolt-reflecting-reflections-dust/>, accessed 22 May 2019. |

| 6 | ‘Reflections in the Dust’, The Backlot Films website, <https://www.thebacklotfilms.com/works/reflections-in-the-dust>, accessed 22 May 2019. |

| 7 | See David Paicu, ‘Interview with Luke Sullivan / Refections [sic] in the Dust’, Film in Revolt, 13 March 2019, <https://www.filminrevolt.org/interview-with-luke-sullivan-refections-in-the-dust/>, accessed 22 May 2019. |

| 8 | Luke Sullivan, quoted in Paicu, ibid. |

| 9 | For more on theatre-maker Bertolt Brecht’s ideas on the separation of audience from work, see ‘Alienation Effect’, Encyclopædia Britannica, <https://www.britannica.com/art/alienation-effect>, accessed 22 May 2019. |

| 10 | ‘Reflections in the Dust’, The Backlot Films website, op. cit. |

| 11 | Dave Crewe, ‘Lady Killers: Hounds of Love, Horror and Violence Against Women’, Metro, no. 193, 2017, pp. 12–7. |

| 12 | See, for example, MaryAnn Johanson, ‘Hounds of Love Movie Review: Serial-killer Porn’, Flick Filosopher, 27 July 2017, <https://www.flickfilosopher.com/2017/07/hounds-love-movie-review-serial-killer-porn.html>, accessed 22 May 2019. |

| 13 | Sullivan, quoted in Paicu, op. cit. |

| 14 | Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, ‘Reflections in the Dust’, Alliance of Women Film Journalists, 21 February 2019, <https://awfj.org/blog/2019/02/21/reflections-in-the-dust-review-by-alexandra-heller-nicholas/>, accessed 22 May 2019. |

| 15 | Luke Sullivan, quoted in Matthew Eeles, ‘Interview: Luke Sullivan’, Cinema Australia, 14 October 2018, <https://cinemaaustralia.com.au/2018/10/14/interview-luke-sullivan/>, accessed 22 May 2019. |

| 16 | Sullivan was twenty-three years old at the time of the film’s release; see Eeles, ibid. |