‘16 Lovers Lane – we deliver this pop jewel and it brings us nothing. Like, financially, nothing. We may as well have put out a free jazz album,’ says Robert Forster, singer/songwriter of the titular band discussed in Kriv Stenders’ documentary The Go-Betweens: Right Here (2017).

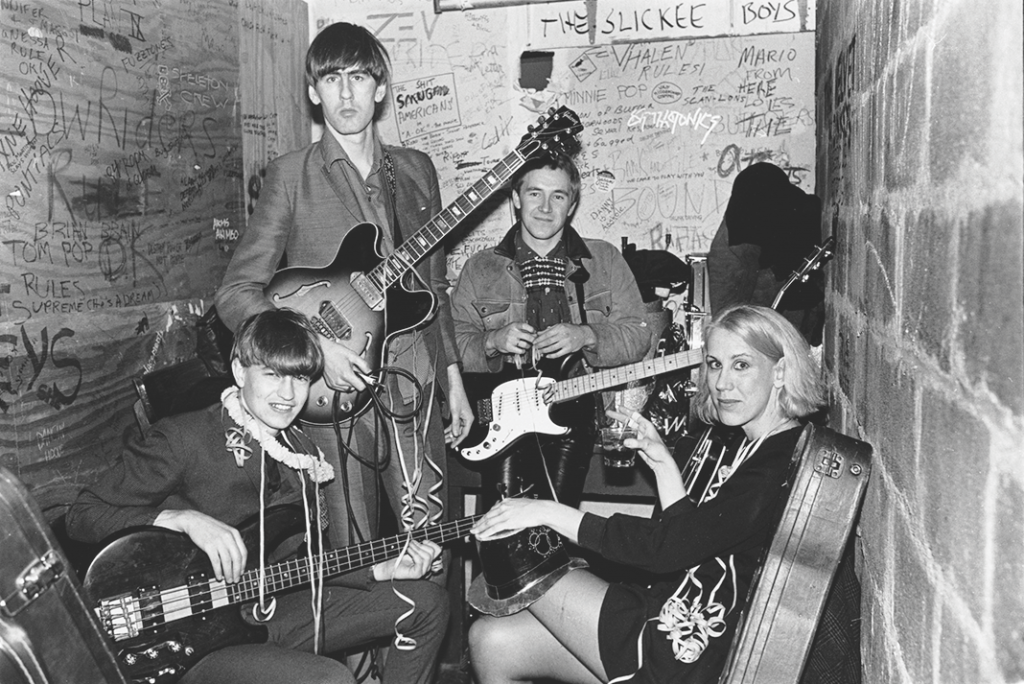

Formed in Brisbane in 1977 by Forster and fellow singer/songwriter Grant McLennan, independent rock band The Go-Betweens attracted little popular attention over their eighteen-year career, which spanned 1977 to 1989 and then 2000 to 2006. Today, however, the group is considered one of the most inventive and important in Australian music history. Testament to this is the fact that, in 2001, the Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA) listed ‘Cattle and Cane’ from the band’s sophomore album, Before Hollywood, as one of the top thirty Australian Songs over the preceding seventy-five years,[1]‘The Songs That Resonate Through the Years: Industry Votes for Top 30 Australian Songs’, media release, APRA, 2 May 2001, available at <http://www.debbiekruger.com/pdfs/aprathirty.pdf>, accessed 9 November 2017. despite the tune having never reached the local charts. Furthermore, in 2009, the Brisbane City Council announced that a new bridge would be named the ‘Go-Between Bridge’ in the band’s honour.[2]See David Barbeler, ‘Brisbane Bridge Honours Legendary Band’, Drive, 29 September 2009, <http://www.drive.com.au/motor-news/brisbane-bridge-honours-legendary-band-20090929-14ab8.html>, accessed 9 November 2017.

Stenders’ documentary is a vital, honest and revelatory portrait of its subjects, telling the stories not only of their songs, but also of their intense and fraught relationships – both platonic and romantic. Rather than adopting a straightforward, expository approach, Stenders creates a collage of interviews, conversations, photographs, video footage, re-enactments, live performances and music recordings. He structures these both chronologically, by presenting events in historical order, and visually, by continually returning to a farmhouse in an unnamed location in Queensland, where contemporary interviews with band members take place. As various players arrive and depart, it becomes clear that the property represents the band itself. The only member missing is McLennan, who tragically died of a heart attack in 2006, at the age of forty-eight.

‘We gathered on my sister’s farm in this old rambling Queensland mansion,’ explains Stenders in an SBS Movies interview,

so it was kind of like ground zero, like Last Year in Marienbad [Alain Resnais, 1961]. They all confessed their stories, so it’s kind of an oral history. The house is very evocative, a really beautiful place and it sort of evokes Grant McLennan who died as he grew up on a Queensland cattle station.[3]Kriv Stenders, quoted in Helen Barlow, ‘Right Here: Finding The Go-Betweens, Kriv Stenders’ New Film, Is Premiering at the Sydney Film Festival’, SBS Movies, 13 June 2017, <http://www.sbs.com.au/movies/article/2017/04/11/right-here-finding-go-betweens-kriv-stenders-new-film-premiering-sydney-film>, accessed 10 November 2017.

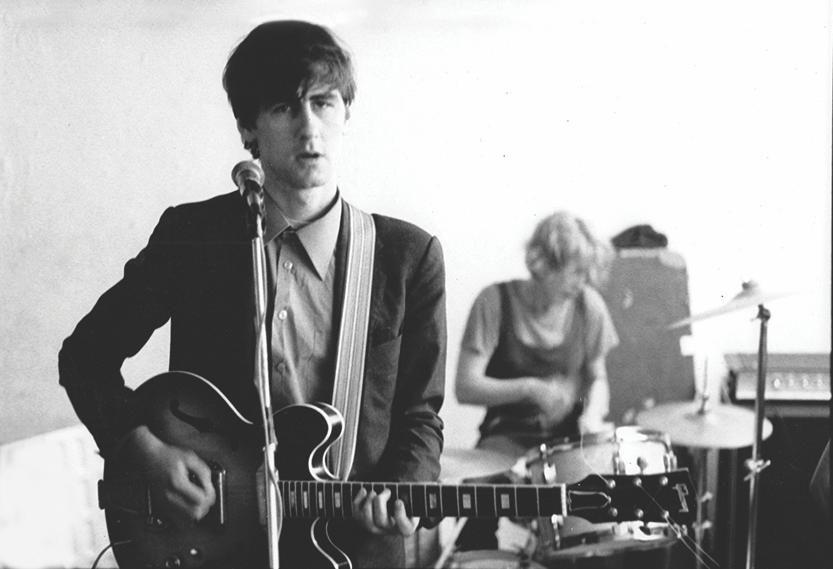

Indeed, the interviewees’ candour is crucial to the film’s success. Shot in close-up, Forster, sitting alone on the mansion’s verandah, describes his first impressions of Lindy Morrison, who became The Go-Betweens’ drummer and with whom he had a romantic relationship. ‘I’d seen Lindy. She was around. She was playing in a band called Xero,’ he says.

She was an actress, too – you know, social worker, drummer, actress. What a resume […] I was watching […] Although she was six years older than me, there was something like a response in me. I wanted to get to know her.

His reminiscences interweave with those of Morrison, also on her own, who recalls seeing Forster emerge from a car – barefoot and wearing blue jeans – and thinking, ‘It was just so sexy […] I’ve always loved intense, nerdy men. They’re my favourite sort of men. It just wasn’t difficult to fall in love with him.’ On one hand, the close-ups generate intimacy for the viewer; on the other, CinemaScope shots of the surrounding farmland, filled with light, rolling pastures and empty sky, give a sense of possibility: this is a space where the mind is bound to wander and where speaking freely is deemed safe because no-one else is around.

Between Forster’s and Morrison’s confessions, Stenders uses archival photographs to plunge the viewer into the pair’s past, including images of Morrison performing with Xero and those of her and Forster sharing a claw-foot bath. Rather than telling the viewer what to think or conveying just one side of the story, the director thus paints a complex, multifaceted picture. As he has explained:

I really wanted to do something where you’re transported by these people’s stories and by the whole history. There’s no narrator or anything like that. It’s very matter-of-fact and you just go bouncing through all these characters as they enter their history.[4]ibid.

Later, the documentary chronicles Forster and McLennan’s decision to terminate the band in 1989, without consulting Morrison or Amanda Brown, at the time The Go-Betweens’ violinist and McLennan’s partner. A point-of-view shot captures Forster staring into a bonfire – cinematic code for reflection and contemplation – before the camera cuts to Morrison and Brown sitting at a table in a darkened room. Brown remembers packing her bags and leaving McLennan immediately, while Morrison says, ‘Both of us refused to be defined as the girlfriends, and that’s what they did, when they dumped us. They treated us like ex-wives, and that was the greatest insult.’

Additionally, the film sheds light on another of the band’s core relationships: the thirty-year-long friendship between Forster and McLennan. From the opening scenes, the viewer learns not only of their mutual commitment to artistic integrity over commercialism, but also of their differences. While establishing shots show Forster walking towards the farmhouse, carrying his guitar, an archival interview plays in voiceover. Forster describes The Go-Betweens’ music in elaborate metaphors – ‘It’s like running water off thin white strips of aluminium […] It’s open fields. It’s sunlight. It’s also Bob Dylan in sunglasses talking to Françoise Hardy’ – while McLennan makes a plain statement: ‘We’re not a trendy band. We’re a groovy band and I like that.’

Elsewhere, Forster compares meeting McLennan in an English class at The University of Queensland in 1975 to a match being lit; he describes his friend as a ‘boy wonder’, ‘far ahead of anyone else’ in his knowledge of film, poetry and music. He also recounts McLennan’s initial refusal to join the band, but then reads a postcard suggesting a change of heart, as the camera scans McLennan’s handwriting. Impressionistic re-enactments feature two young, male figures speaking in a corridor and sword fighting outside a boarded-up picture theatre. There’s a sense of two kindred spirits sharing a strong, idealistic bond, based on a mutual passionate pursuit of the arts. ‘We were troublemakers; we were dreamers. It took off from that moment,’ Forster says. However, he also admits to their competitiveness, likening their dynamic to that of two drivers: McLennan at first appearing in his rear-view mirror, but then overtaking him, then slipping behind, then overtaking him again.

‘It’s a tricky story to tell because there are so many personal dynamics in the band,’ Stenders muses, ‘but that’s also part of the magic. It’s a saga and that’s what I wanted to convey: the highs and lows and the joy and the pain of being in a band.’[5]Kriv Stenders, quoted in Megan Lehmann, ‘Q&A: Kriv Stenders, Filmmaker, 52’, The Weekend Australian Magazine, 23 September 2017, <http://www.theaustralian.com.au/life/weekend-australian-magazine/qa-kriv-stenders-filmmaker-52/news-story/a939a1a6b63d044c5e7c5100b037b666>, accessed 10 November 2017.

In addition to tracing the vicissitudes of the band members’ personal relationships, the documentary explores what made their music idiosyncratic. Again, Stenders steers clear of didacticism here, instead building a kaleidoscope of suggestions and leaving the viewer to piece them together. Essential to this picture is the historical, political and social context, which Stenders depicts by introducing several contemporaries of The Go-Betweens. These interviews are shot in black-and-white and close-up against an unidentifiable, black backdrop, drawing the viewer’s focus to their words. In this way, the speakers are established as commentators, in contrast to the film’s ‘protagonists’ – the band members – who speak from the farmhouse.

‘Brisbane felt very insular,’ recalls Mark Callaghan, singer/songwriter for The Riptides and GANGgajang.

I remember that there was nothing open after six o’clock. You got the sense that you weren’t supposed to rock the boat and that anyone under twenty-five was a target, and you were always aware of the police.

Across the screen flashes photographs and fast-motion footage of mannequins in shopfront windows, dressed in 1970s fashion; young people dancing on suburban lawns and drinking in gutters; protest signs; and, perhaps surprisingly for viewers unfamiliar with Queensland’s history, police lines. It’s a world that feels typically Australian, filled with sunlight and ample leisure time, but the overpowering police presence creates an unsettling contrast. Another interviewee, author and screenwriter Gerard Lee, recollects:

But, you know, when you grow up with it, you learn to find freedom in the small ways that you can. Sometimes, it was scary going out at night because, if the cops got you and you were wearing some kind of multicoloured beanie or ugg boots or something, well, that’s an hour or two out of your life while they torment you.

Stylistically, these historical images – presented with up-tempo pacing and in faded colouring – call to mind the music video for ‘Streets of Your Town’, The Go-Betweens’ highest-charting song. Not coincidentally, Stenders co-directed[6]The 1988 music video was co-directed with Antony Clare. it, too.

While this adversarial atmosphere spawned numerous highly politicised bands, The Go-Betweens preferred a more personal, poetic voice. As writer Clinton Walker, a friend of the band, explains:

It didn’t take a lot of imagination to go, ‘I’m going to form a politicised rock band that’s protesting the political regime’ […] I don’t belittle that, but that’s not rocket science – and, if you’ve got some real imagination, you might think, ‘What’s something else I could do?’

Yet this is not the only element, according to the film, that made The Go-Betweens unique. There was also the unusual way in which the band formed: out of friendship, rather than a meeting of musicians. Forster, for instance, was already writing songs and playing in The Godots when he met McLennan. ‘I had this realisation,’ he recalls. ‘It was better to work with a friend who didn’t play an instrument but was entirely on your wavelength, as opposed to musicians who could obviously play but weren’t on your wavelength.’ While the Forster–McLennan partnership formed the band’s core, other members – particularly Morrison and Brown – played a crucial role in shaping their sound and developing their ethic. As Morrison recounts, ‘I wanted the band rehearsing every day. That’s what I wanted. I was in the pocket with them because we spent so many hours just playing, over and over and over.’

The Go-Betweens: Right Here is a dynamic, dense and fast-paced film that turns the lens on one of Australia’s most distinctive rock bands. In documenting The Go-Betweens’ complicated story – from the moment Forster and McLennan met as university students to McLennan’s passing – Stenders has employed a deft touch. He rejects conventional, linear narration in favour of pluralism, allowing all surviving band members to speak openly. Their memories and confessions are supported, enhanced and, occasionally, contradicted by a wealth of archival material, and bolstered by perhaps the most powerful storytelling tool of all: The Go-Betweens’ enduring songs themselves.

https://clickv.ie/w/metro/the-go-betweens

Endnotes

| 1 | ‘The Songs That Resonate Through the Years: Industry Votes for Top 30 Australian Songs’, media release, APRA, 2 May 2001, available at <http://www.debbiekruger.com/pdfs/aprathirty.pdf>, accessed 9 November 2017. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See David Barbeler, ‘Brisbane Bridge Honours Legendary Band’, Drive, 29 September 2009, <http://www.drive.com.au/motor-news/brisbane-bridge-honours-legendary-band-20090929-14ab8.html>, accessed 9 November 2017. |

| 3 | Kriv Stenders, quoted in Helen Barlow, ‘Right Here: Finding The Go-Betweens, Kriv Stenders’ New Film, Is Premiering at the Sydney Film Festival’, SBS Movies, 13 June 2017, <http://www.sbs.com.au/movies/article/2017/04/11/right-here-finding-go-betweens-kriv-stenders-new-film-premiering-sydney-film>, accessed 10 November 2017. |

| 4 | ibid. |

| 5 | Kriv Stenders, quoted in Megan Lehmann, ‘Q&A: Kriv Stenders, Filmmaker, 52’, The Weekend Australian Magazine, 23 September 2017, <http://www.theaustralian.com.au/life/weekend-australian-magazine/qa-kriv-stenders-filmmaker-52/news-story/a939a1a6b63d044c5e7c5100b037b666>, accessed 10 November 2017. |

| 6 | The 1988 music video was co-directed with Antony Clare. |