Directed by Steven Kastrissios, Bloodlands (2017) is a co-production between Australia and the Republic of Albania, a small European country nestled on the south-west of the Balkan Peninsula. Yet the folklore, culture and history that lie at the core of this film are thousands of miles away – literally and figuratively – from The Horseman (2008), the director’s distinctly Australian debut. While The Horseman’s title is riddled with the apocalyptic overtones of the Book of Revelation, its folkloric associations with ‘Banjo’ Paterson’s iconic 1890 poem ‘The Man from Snowy River’ underscore its essential ‘Australianness’.

The Horseman tells the story of Christian (Peter Marshall), whose teenage daughter Jesse (Hannah Levien) has died of a heroin overdose. When an anonymously sent adult movie called Young City Sluts 2, which includes footage of a visibly drugged Jesse having sex with three men, arrives by post, Christian is sparked into a vigilante mission for revenge. He locates those involved in the production and kills them one by one, along the way gathering information about other guilty parties. On his journey, he meets teen hitchhiker Alice (Caroline Marohasy) and, through their relationship, Christian begins to face his grief and guilt over Jesse’s death. But, as the film’s brutal conclusion reveals, this is too little too late, and both he and Alice are forced to face the consequences of his decision to take the law into his own hands.

Like The Horseman, Bloodlands evinces an intrinsic fascination with family ties, loyalty, disruption and vengeance; however, it not only shifts the narrative’s cultural context, but also takes its generic focus to unambiguously supernatural terrain. So how did an Australian who had never been to Albania before and who does not speak the language end up making the first Albanian horror film,[1]‘First Ever Albanian Horror Movie Makes World Premiere’, Tirana Times, 3 March 2017, <http://www.tiranatimes.com/?p=131461>, accessed 19 October 2017. and what are the results?

Entering the terrain

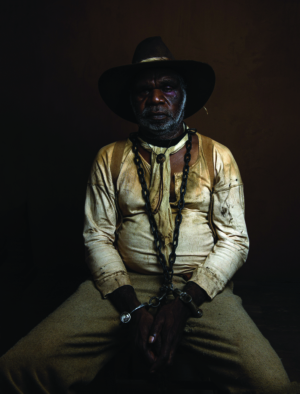

Set in a mountainous Albanian village where encroaching modernity takes the form of ubiquitous construction, Bloodlands follows struggling local butcher Skender (well-known Albanian actor Gëzim Rudi); his wife, Shpresa (Suela Bako, who won Best Actress in the ‘Graveyard Shift’ sidebar of the 2017 Nashville Film Festival for her performance); and their two adult children, Artan (Emiljano Palali) and Iliriana (Alesia Xhemalaj). Facing impending bankruptcy, and with Artan urging him to slow down for the sake of his health, Skender clings to the veneer of paternal authority despite the reality that surrounds the family so visibly undermining it. He rejects Shpresa’s offer to return to work to help support the family, and husband and wife become fixated on the supposed damage to their reputation within the extended family that their impending, seemingly inevitable downfall would bring.

But change is coming whether the family can control it or not. On the back of Iliriana’s declaration that she intends to move to Italy with a friend (a mission supported by her mother, without her father’s knowledge), Skender and his kin face a more immediate and peculiar threat in the form of the witch-like figure known as the shtriga (played by Ilire Vinca Celaj). Skender’s unthinking hostilities towards a couple of feral youngsters scavenging for pet food outside his shop inadvertently rekindle long-held tensions between Shpresa’s family and the shtriga, who acts as surrogate mother to these seemingly homeless young people and some mysterious others who have found a home with her. This reactivates a long-repressed blood feud between the shtriga, along with her ‘children’, and the already-desperate family.

An Australian director of Greek heritage, Kastrissios was just twenty-four years old when he made The Horseman; after its success, he attempted to branch out: he fiddled with a number of projects across a range of genres, and even considered directing scripts written by other people. But it was his relationship with friend – and soon-to-be producer – Dritan Arbana that would spark the origins of Bloodlands. Although based in Sydney, the Albanian Arbana enthralled Kastrissios over coffee with stories about his homeland, particularly the blood feuds that are so much a part of its complex history. Inspired by the tales his friend had told him, Kastrissios wrote a script. Arriving in Albania a few months later, the filmmaker found that his experiences in the region and contact with locals had given him ‘confidence […] that the story [he had] written in Sydney felt authentic to Albania’.[2]Steven Kastrissios, quoted in ‘Ahead of the World Premiere of His Latest Film Bloodlands at Horror Channel FrightFest Glasgow, Steven Kastrissios Discusses the Challenges of Making the World’s First Albanian / Australian Horror Film’, media release, Clout Communications, 20 February 2017, <http://cloutcom.co.uk/ahead-world-premiere-latest-film-bloodlands-horror-channel-frightfest-glasgow-steven-kastrissios-discusses-challenges-making-worlds-first-albanian-australian-ho/>, accessed 26 October 2017. Despite Arbana’s lack of experience as a producer (he is an actor by trade) and Kastrissios’ only very recent interest in the country and its culture,[3]Caris Bizzaca, ‘Coming Soon: Bloodlands’, Screen Australia website, 20 January 2016, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/sa/screen-news/2016/01-20-coming-soon-bloodlands>, accessed 19 October 2017. they found themselves on track to make Albania’s first horror film.

Directing a movie with a primarily monolingual, non-English-speaking cast proved less of a challenge to Kastrissios than might be assumed. He worked closely with a team of translators and – having largely based the protagonists on his own family members – had an intuitive sense of how characterisation should develop. The decision to feature the language of the country in which he was shooting was an important one for him, despite warnings from industry peers that making a film in a language other than English might hurt sales and distribution. But Kastrissios was firm: ‘Albanian is an ancient language rarely heard outside of the region and it’s one of the few that has no root in other languages, so we should preserve it.’[4]Kastrissios, quoted in ‘Ahead of the World Premiere’, op. cit.

Which, of course, raises the question: given Bloodlands is the country’s first horror film, why task its creation to an outsider? Again, Kastrissios has spoken frankly: while Albania once had a small but stable film industry, mostly producing propaganda films during the Soviet era, today there are ‘limited opportunities’; coupled with the lack of experienced special-effects, make-up and stunt professionals, this means it would be ‘difficult for any budding local genre filmmakers’ to create work there.[5]ibid. But Kastrissios’ background in post-production and experience making The Horseman meant he had the skill set to pull off what was required to produce a film efficiently, especially as ‘in Albania […] the Australian dollar goes a long way’.[6]Kastrissios, in Bizzaca, op. cit.

Embracing the darkness

Built atop Bloodlands’ core family drama is a narrative about crumbling patriarchy and the rise of a forward-thinking youth. To achieve this, the film brings together two specific aspects of Albanian culture: the country’s entrenched historical disposition for blood feuds and the folkloric figure of the shtriga. These, in turn, feed back into a story that dramatises Skender’s inevitable failure to maintain his aggressive (and, at times, almost abusive) position as the family’s leader, and the unacknowledged yet omnipresent centrality of women to a culture that – superficially, at least – appears to be unambiguously male-dominated.

The legacy of the blood-feud tradition – known in the region as gjakmarrja (‘blood-taking’) or hakmarrja (‘revenge’) – is made explicit in Bloodlands’ opening moments, with an intertitle explaining:

Ancient Albanian canon, as written in the Kanun of Lek, dictates societal rules including marriage, property rights, hospitality and sanctioned murder. Modern Albania has largely forgotten this way of life, however some traditions of the Kanun still linger in parts of the country.

The complex, enduring Kanun of Lek gained its name from fifteenth-century tribal chieftain Lekë Dukagjini, who formalised widely recognised customs in order to regulate norms that had previously resulted in barbarous chaos. In the case of blood feuds, while not seeking to eradicate the practice altogether, the Kanun sought regimentation to reduce its frequency and to dissuade future feuds.[7]Miranda Vickers & James Pettifer, Albania: From Anarchy to a Balkan Identity, Hurst & Company, London, 1997, p. 132. According to Clarissa de Waal, the Kanun was the dominant legal system in the tribal north of Albania until 1945, where its influence was equally strong in both Muslim and Christian regions. Notably, it was a largely oral tradition that was not recorded officially until 1913 and, while it was first published in 1933, it was later banned under communism.[8]Clarissa de Waal, Albania Today: A Portrait of Post-communist Turbulence, I.B.Tauris, London & New York, 2005, pp. 72–3.

Soviet rule played a crucial role in facilitating modern adherence to the Kanun, particularly the practice of blood feuds. Following the fall of communism, the Kanun provided a sense of tradition and structure that was, by then, missing, while simultaneously acting as a symbolic return to an indigenous belief system suppressed under the Soviet regime, which believed (incorrectly) that it had been eradicated. During the so-called Winter of Anarchy of 1991–1992, Albania saw years of pent-up grievances and vendettas erupt, the country swept by revenge killings enacted under the name of the Kanun. Miranda Vickers and James Pettifer recount that, ‘in the first half of 1992 there were nineteen blood-feud murders around the city of Shkoder’ alone. The government’s response was to increase policing and, by 1993, there were fifteen executions in Albania’s capital, Tirana, in line with national death-penalty laws for murder.[9]Vickers & Pettifer, op. cit., p. 133.

Despite Bloodlands’ arresting depictions of blood feuds and the shtriga, the theme that prevails overall is that of familial tensions – something underscored even more solidly by the dynamics between past and present.

The history of Albanian blood feuds infuses Bloodlands’ tale of revenge, murder, honour and gender dynamics, but it amplifies the theme of gender by including depictions of the shtriga. A female vampire-witch figure that exists in the folklore of a number of cultures across the region, the shtriga is usually conceived of as an older woman with remarkable supernatural powers and a penchant for cannibalism.[10]Robert Elsie, A Dictionary of Albanian Religion, Mythology, and Folk Culture, Hurst & Company, London, 2001, p. 236. She can often ‘pass’ as an ordinary person and even attend church, but can be identified by her inability to walk underneath a crucifix made of pig bones.[11]Theresa Bane, Encyclopedia of Giants and Humanoids in Myth, Legend and Folklore, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC, 2016, p. 136. She may also vomit the blood of her victims,[12]ibid. a trait portrayed in Bloodlands through the heavily ritualised ‘blood play’ between the shtriga and her ‘family’ of followers. The film’s final revelation – the backstory of the blood feud between the shtriga and Shpresa’s family – also foregrounds the mythological connection between the shtriga, fertility and motherhood. We learn that the shtriga was herself a victim of a man’s cruelty, and it was this that sparked her monstrosity – not only towards the family against whom she seeks vengeance, but also in relation to her own power. Much like other ‘mother goddess’ figures that have manifested around the world since ancient times, for the shtriga, motherhood becomes a way to gain strength (in her case, to build an army), rather than being what it had been for her previously: a cause of sadness and weakness.

Yet, despite Bloodlands’ arresting depictions of blood feuds and the shtriga, the theme that prevails overall is that of familial tensions – something underscored even more solidly by the dynamics between past (the rural village setting; a narratively significant visit to the local government archive; Albania’s dark traditions; and the literal return of the dead to the world of the living) and present (encroaching modern construction; the ambitions of the nation’s youth, represented convincingly by Artan and Iliriana’s rejection of their parents’ way of life). Skender and Shpresa themselves embody a tie not only to the Kanun of Lek, but also to the country’s history: their fury and bitterness were spawned from their hardships living under Soviet rule and the horrific results of its collapse in the early 1990s. The film’s final image of the children ritually burning the bodies of their parents marks both a tie to tradition and – more significantly – a move away from the archaic, regressive world they represented. If this theme was not clear earlier, here it is made explicit: Artan and Iliriana are ambassadors for all Albanian youth, the film urging them to find a path beyond the superstitions and hegemony of the past while remaining loyal to family. By conquering the shtriga and cremating their parents, a distinct and explicit disconnection is made with Old Albania as they move into the future. The cord is cut.

In a similarly tradition-challenging vein, Kastrissios’ globalised approach to filmmaking, born of his own multicultural social world in Australia, has granted him the good fortune of identifying the potential of making a horror film in Albania. His is a forward-looking practice, one that sees beyond geographic and generic boundaries, and shows us a potential future beyond the archaic, restrictive parameters of ‘national cinema’.

Endnotes

| 1 | ‘First Ever Albanian Horror Movie Makes World Premiere’, Tirana Times, 3 March 2017, <http://www.tiranatimes.com/?p=131461>, accessed 19 October 2017. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Steven Kastrissios, quoted in ‘Ahead of the World Premiere of His Latest Film Bloodlands at Horror Channel FrightFest Glasgow, Steven Kastrissios Discusses the Challenges of Making the World’s First Albanian / Australian Horror Film’, media release, Clout Communications, 20 February 2017, <http://cloutcom.co.uk/ahead-world-premiere-latest-film-bloodlands-horror-channel-frightfest-glasgow-steven-kastrissios-discusses-challenges-making-worlds-first-albanian-australian-ho/>, accessed 26 October 2017. |

| 3 | Caris Bizzaca, ‘Coming Soon: Bloodlands’, Screen Australia website, 20 January 2016, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/sa/screen-news/2016/01-20-coming-soon-bloodlands>, accessed 19 October 2017. |

| 4 | Kastrissios, quoted in ‘Ahead of the World Premiere’, op. cit. |

| 5 | ibid. |

| 6 | Kastrissios, in Bizzaca, op. cit. |

| 7 | Miranda Vickers & James Pettifer, Albania: From Anarchy to a Balkan Identity, Hurst & Company, London, 1997, p. 132. |

| 8 | Clarissa de Waal, Albania Today: A Portrait of Post-communist Turbulence, I.B.Tauris, London & New York, 2005, pp. 72–3. |

| 9 | Vickers & Pettifer, op. cit., p. 133. |

| 10 | Robert Elsie, A Dictionary of Albanian Religion, Mythology, and Folk Culture, Hurst & Company, London, 2001, p. 236. |

| 11 | Theresa Bane, Encyclopedia of Giants and Humanoids in Myth, Legend and Folklore, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC, 2016, p. 136. |

| 12 | ibid. |