An Australian–US co-production directed by Chris Peckover, who co-wrote the script with Zack Kahn, Better Watch Out (2016) is an immensely fun black comedy replete with horror tropes – as humorous as it is disturbing. It sets up a typical babysitter-versus-home-invader scenario before unexpectedly veering into a study of the twisted desires of a twelve-year-old psychopath. The film is about the moral panic surrounding adolescence, particularly the surge of hormones that leads to volatile emotions and risky behaviour. It also serves as a derisive critique of privilege, depicting the darkness concealed behind the charming picket fences of upper-middle-class suburban houses – and the dangerous expectation of male teens that they can do and have what they want, without consequence.

After a limited festival release under the fairly generic title of Safe Neighbourhood, Better Watch Out was shrewdly renamed to better reflect its yuletide-themed terrors. This is unambiguously a Christmas film. It opens with ‘Joy to the World’ playing over an idyllic winter scene: a nostalgia-laced image of an affluent suburb piled with fresh snow, its houses adorned with festive decorations. Carollers wander and children play alone outdoors, seemingly delightful until they knock the head off a snowman – an abrupt signal of the violence ahead. But, while Better Watch Out is clearly indebted to Chris Columbus’ beloved family holiday movie Home Alone (1990), it also exemplifies the holiday-horror subgenre, alongside the prototypical the-calls-are-coming-from-inside-the-house slasher Black Christmas (Bob Clark, 1974) and the creature-feature comedy Gremlins (Joe Dante, 1984). Additionally, it mirrors more explicit yuletide offerings like serial-killers-in-Santa-suits titles Christmas Evil (Lewis Jackson, 1980), Silent Night, Deadly Night (Charles E Sellier Jr, 1984) and Santa Claws (John A Russo, 1996). Peckover emphasises this Christmas milieu, as when the film shows a silly light-up Santa appearing inside a house and, later, a hostage tied up with fairy lights.

The film takes place almost entirely inside a family home, a stylish, purpose-built single-location setting created by production designer Richard Hobbs, the supervising art director of Mad Max: Fury Road (George Miller, 2015).[1]Kaitlyn Tiffany, ‘Better Watch Out Is a Surprising, Strange Christmas Horror-comedy About Idiotic Boys’, The Verge, 3 October 2017, <https://www.theverge.com/2017/10/3/16375490/better-watch-out-horror-movie-review-halloween>, accessed 15 October 2017. Ashley (Olivia DeJonge) is there to babysit twelve-year-old Luke (Levi Miller), the only child of Robert (Patrick Warburton) and Deandra (Virginia Madsen). The latter two are charming stereotypes of suburban parents, leaving money for pizza and instructions to be in bed by eleven. Warburton displays his signature deadpan, with Robert deploying some classic ‘dad humour’ – at Deandra’s faux-exasperation at his ugly Christmas tie, he teasingly switches it to an equally kitsch one hidden inside his coat. His wife seems similarly good-humoured: upon opening Luke’s bedroom door at an inopportune moment, catching his best friend Garrett (Ed Oxenbould) agreeing he’d love him to ‘get some ass’, she lets him clumsily try to recover. Garrett is a bad influence, she warns Luke, presumably unaware of the weed the latter has acquired from the former’s brother. This easy passing of blame – her ‘not my child’ certainty – is myopic; she obviously has no idea about Luke’s inner life.

Luke’s plan for the evening is, unexpectedly, to have sex with Ashley. He has had a crush on her for years and, now that she is moving, it is his last chance. This is a familiar plotline in films involving teens, except usually the goal is a kiss and the protagonist is significantly older. It’s clear that seventeen-year-old Ashley is not going to have extremely inappropriate relations with the child she is responsible for, but Luke’s puppy love is uncomfortably clumsy and confident; we are encouraged to laugh at his transparent efforts. He puts on a horror movie – a signal that he believes he is no longer a kid – yet rests his head on Ashley’s shoulder as though he is scared, a typical move for the girl in such a scenario. He also declares his maturity by guzzling champagne from the bottle, bragging about how well he can hold his alcohol. When he ignores Ashley’s firm rebuffs and kisses her, she rebukes him in an authoritative tone, desperate to re-establish boundaries. Luke is indignant at being treated like a child. He is almost thirteen, he argues – a particularly childish retort – and there is a five-year age gap between his parents. Ashley softens, consoling him by saying she would date him if they were the same age. The implications of Luke’s crush evolve: initially it seems juvenile and misguided, but his blinkered persistence and rejection of boundaries soon become obnoxious, then wholly terrifying.

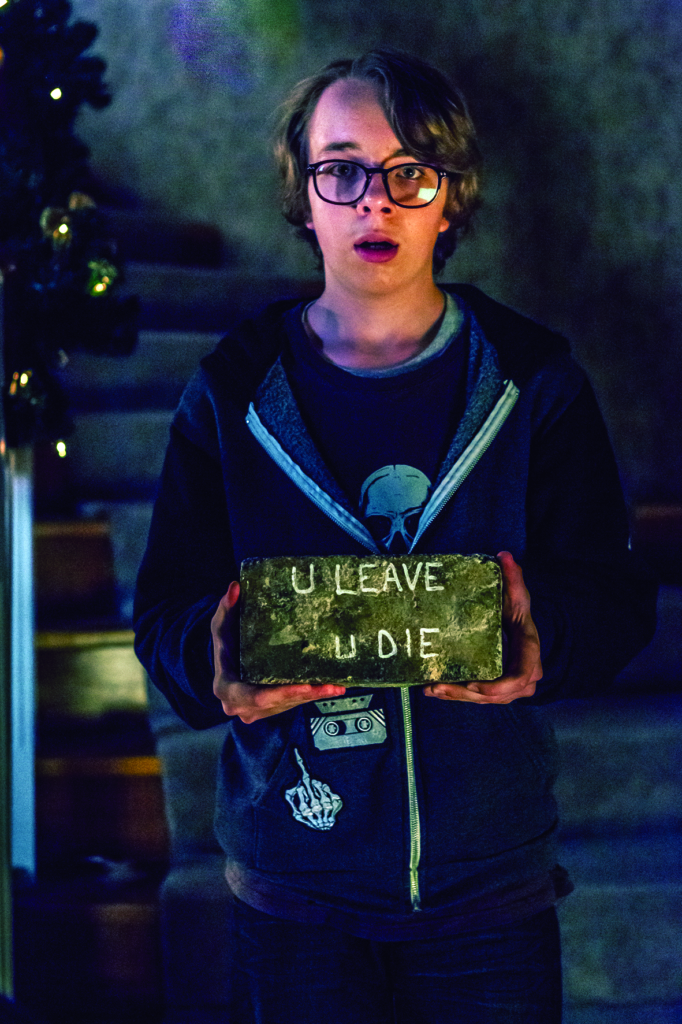

The problem of this disobedient, slightly intoxicated twelve-year-old is overshadowed by the home invasion. The pair are besieged by classic horror scenarios: prank calls, a brick through the window warning ‘U LEAVE U DIE’ and a masked figure with a shotgun patrolling the hallway. Ashley’s tyres are slashed; the phone line, cut; and the internet, disabled. Indeed, Better Watch Out is a loving homage to the horror genre, with a catalogue of aural and visual tropes: eyes peeping through cracks, a silhouette at the window, a locked door found ajar, rustling noises outside, a jump-scare because of a spider. One shot from behind a faintly moving swing in the backyard looks towards the open back door, establishing the intruder’s entrance. In the horror movie they are watching, a scared woman says, ‘I want to leave’ – dialogue that always precedes a terrible occurrence – before Ashley is startled by a noise outside. When she, reasonably, asks, ‘Why would they go into the attic?’ she pre-empts their own retreat to this space.

Better Watch Out is a loving homage to the horror genre, with a catalogue of aural and visual tropes: eyes peeping through cracks, a silhouette at the window, a locked door found ajar, rustling noises outside, a jump-scare because of a spider.

These sequences are so pointedly self-aware, so heavy-handed with references, that it’s a relief to get to the fairly obvious reveal: the intruder is Garrett. Hiding in the wardrobe – Ashley peeking out of the slats like Laurie (Jamie Lee Curtis) in Halloween (John Carpenter, 1978), watching the intruder look under the bed – she eventually realises and is furious, admonishing Luke, ‘You need therapy – lots of it.’ Yet this obviously ill-fated plan was a ruse, a soft twist distracting the viewer from the moment in which Luke hits her and she tumbles down the stairs. When she awakens taped to a chair, we become witnesses to the sort of closed-case incident uncovered in the backstories of violent killers. Yet, though Luke’s enjoyment from tormenting her recalls Funny Games (Michael Haneke, 1997 & 2007), Better Watch Out is nowhere near as serious or depraved.

Ashley is a typical Final Girl, a young and attractive babysitter like Halloween’s Laurie or Jill (Carol Kane) from When a Stranger Calls (Fred Walton, 1979). She is easily startled – a fact established in her first scene, when she nearly runs over a black cat – yet she rises to the occasion when faced with the intruder, creeping up the stairs brandishing a knife during an archetypal Final Girl moment. Once Luke has her tied up, she tries reprimanding, reasoning, complying and escaping, desperate to survive. In a scene reminiscent of Helen’s (Sarah Michelle Gellar) death in I Know What You Did Last Summer (Jim Gillespie, 1997), Ashley almost gets away, just within reach of a crowd, her struggle drowned out by carollers.

But Peckover has also built a metanarrative about the horror genre. This is encapsulated in the motivation behind Luke’s cruel and dangerous hoax. Early in the film, the boys discuss an article in men’s magazine Maxim claiming that women are aroused by horror movies. Luke has planned to terrify Ashley, play the hero, and be rewarded with her resultant dopamine rush and uncontrollable lust. This strategy reflects the (narrow) presumption that horror is made for adolescent boys, and the pervasive belief – borne out in a 1986 study – that, in heterosexual pairings, men prefer frightened women, and women, brave men.[2]Dolf Zillmann et al., ‘Effects of an Opposite-gender Companion’s Affect to Horror on Distress, Delight, and Attraction’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 51, no. 3, 1986, pp. 586–94. Gender coding is noticeably present in horror films, with women in particular punished for having – and acting on – sexual desires. The decision to make the boys so young in Better Watch Out highlights the persistent moral anxiety about sexual development, a frightening visualisation of the saying ‘boys will be boys’. We are repeatedly reminded of their age: Luke’s voice cracks, and he shrieks at Garrett for smoking pot inside, as his mum might smell it. Yet they discuss women in an aggressively lewd way, seeming too mature for their age, while also reflecting an apparently ingrained contempt for women. For example, in a game of Kill, Fuck, Marry based on Adventure Time, Luke enthuses about the sexual potential of Princess Bubblegum. When he subsequently initiates a game of Truth or Dare – another marker of teenage behaviour – Garrett tells him to touch Ashley’s breast, and Luke smirks, relishing her distress.

The film proposes that adults never really know who their children are. It references the ‘evil child’ trope, though Luke is slightly too grown-up to be as frightening as younger children like Damien (Harvey Stephens) from The Omen (Richard Donner, 1976) or Rhoda (Patty McCormack) from The Bad Seed (Mervyn LeRoy, 1956). He is more comparable to twelve-year-old Regan (Linda Blair) from The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973) and fourteen-year-olds Anne (Jeanne Goupil) and Lore (Catherine Wagener) from Don’t Deliver Us from Evil (Joël Séria, 1971). On the cusp of puberty, Luke embodies the often overwhelming and distressing physical and mental changes that pre-teens experience. Yet this is a recurring theme usually present in horror films featuring female protagonists, especially in the possession subgenre, in which teen women are favoured ‘vessels’ of demons. Luke is decisively self-assured, and his palpable satisfaction when harming others evokes recent films about violent teens, like Them (David Moreau & Xavier Palud, 2006) and The Strangers (Bryan Bertino, 2008). All of these examples emphasise that teenagers are dangerous – immature, unpredictable risk-takers.

Luke’s actions stem from his refusal to accept his thwarted desires. He is the embodiment of solipsism, and is as much a comment on male privilege as on fears about spoilt children.

The true surprise is that Luke is a convincing psychopath. He is inventive, capable and deeply disturbed – a silver-tongued narcissist who brags, ‘I am the Harry Houdini of getting away with it.’ Ashley’s revelation that he killed Garrett’s hamster is a predictable signpost of his budding psychopathy. He is sadistic and exhilarated by his power. There is an escalation of violence once Luke commits to a new plan, redirecting his delayed gratification to vengeance. He lures Ashley’s ex-boyfriend Ricky (Aleks Mikic) and current beau Jeremy (Dacre Montgomery) to the house. Intimidated by her sexual past, Luke decides to eliminate the competition – they don’t treat her right, he insists. It is unsurprising that they both underestimate him. After knocking Ricky out, Luke continues to swing a baseball bat at his head, dancing as he asks, ‘Isn’t this exciting?’ Once Ricky becomes the second hostage, the film builds to some over-the-top gore. ‘You’re fucking Home Alone–ing him?’ exclaims Garrett, as Luke re-creates the scene of a paint tin swung from a banister. The camera avoids the disgusting outcome, focusing on Ricky’s feet splattered with blood and yellow paint. Luke sets Jeremy up to take the fall, convincing him to write Ashley an apology that serves as a suicide note, before creatively hanging him from his swing using the ride-on mower.

Luke’s actions stem from his refusal to accept his thwarted desires. He is the embodiment of solipsism, and is as much a comment on male privilege as on fears about spoilt children. When Garrett finally decides to help Ashley – he was obviously blindsided by the events – Luke shoots him, protesting, ‘Why did you make me do it?’ He similarly blames Ashley, who, he feels, deserves punishment for not reciprocating his feelings. He treats her like an object, metaphorically and then physically – she is a prize that he demands. His narcissism is exemplified when he screams that she could not possibly know what it’s like to love someone as much as he loves her.

But it is not Ashley’s love that Luke really wants – it is his mother’s. This predictable manifestation of the Oedipus complex was implied at the film’s beginning, when Garrett mocked Luke’s uterine sound machine. Luke shouts at Ashley that his mother no longer hugs him to sleep, his childlike yearning at odds with his violent actions. He acknowledges Ashley’s role as surrogate mother by performing the maternal actions he misses as he stabs her, saying ‘goodnight’ and kissing her on the forehead.

Preparing for his parents’ return, Luke dances to carols while cleaning up, in a montage recalling both Risky Business (Paul Brickman, 1983) and CSI that illustrates his deep lack of empathy. Upon discovering Luke unhurt – he feigns having been asleep throughout the horrific carnage downstairs – his mother tenderly embraces him. It seems he has gained the attention he has so craved. However, there is a twist: Ashley is found alive. This was tipped off by the earlier revelation that she is still a virgin – a fact that, according to slasher conventions, ensures the Final Girl’s survival. As she is wheeled into an ambulance, she sticks her middle finger up at Luke: a final ‘fuck you’ to his manipulative, murderous desires that he assumed he could get away with.

Endnotes

| 1 | Kaitlyn Tiffany, ‘Better Watch Out Is a Surprising, Strange Christmas Horror-comedy About Idiotic Boys’, The Verge, 3 October 2017, <https://www.theverge.com/2017/10/3/16375490/better-watch-out-horror-movie-review-halloween>, accessed 15 October 2017. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Dolf Zillmann et al., ‘Effects of an Opposite-gender Companion’s Affect to Horror on Distress, Delight, and Attraction’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 51, no. 3, 1986, pp. 586–94. |