There is a particular photograph of David McComb, taken when he was about seven or eight years old, that appears for a fraction of a second in the seventh minute of Jonathan Alley’s documentary Love in Bright Landscapes: The Story of David McComb of The Triffids (2021). In the photo, McComb stands with tousled blonde hair against a backdrop of an expansive Western Australian landscape and sky. He is smiling – nay, beaming – as he grasps, or even cuddles, two grey rabbits that are limp, stiff, inert: clearly dead. The juxtaposition between the ecstatic delight of childhood and the corporeal finality of death is potent; the picture might be passed off as a work of art photography in a different context.

In this image we have a neat reflection of the dualities at play in the life and work of one of Australia’s most truly original rock musicians: glorious, playful innocence dances with the macabre and even demonic; the performative, with the introspective; the commercial, with the experimental; the metropolitan, with the rural; Australia, with Europe. Listen to any of the five compelling studio albums by the band McComb fronted, The Triffids, and you are confronted with the friction and energy born of these paradoxes.

Love in Bright Landscapes explores all these things – and more – sensitively and thoroughly, while remaining firmly grounded. Alley’s film is an admirable tribute to a remarkable talent that never tips over into mythologisation, or into the perilous (and common) trap of apotheosising the brooding artist who died too young.

That said, Alley’s film does not do things by halves. As well as featuring excerpts from no fewer than seventy-four songs, it draws on interviews with a dizzying number of friends, family members, musicians, critics and associates to tell McComb’s story from his early life in Perth to his untimely death in 1999 at the age of thirty-six. These interviews are interwoven with photos and home-video footage, live performances, interviews with McComb himself, and author and Triffids fan DBC Pierre reciting McComb’s poetry, letters and journals.

The film is far from experimental; to describe it as conventional or safe may sound critical, but in fact Alley’s commitment to simplicity … is among Love in Bright Landscapes’ greatest strengths.

The film takes a linear, chronological approach to its storytelling, but departs from this frequently to tangentially address certain aspects of McComb’s life that constantly affected him – including his chronic ill health, tempestuous personal relationships and love of art, film and books. This allows the film an attractive looseness that rewards multiple viewings. But the film is far from experimental; to describe it as conventional or safe may sound critical, but in fact Alley’s commitment to simplicity – by allowing McComb’s friends and family to dominate the narrative rather than relying on a technique like illustration or animation, as has been common in music documentary in recent times[1]See, for example, Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds with Shane MacGowan (Julien Temple, 2020), Slim & I (Kriv Stenders, 2020), Waiting: The Van Duren Story (Greg Carey & Wade Jackson, 2018) and Searching for Sugar Man (Malik Bendjelloul, 2012). – is among Love in Bright Landscapes’ greatest strengths.

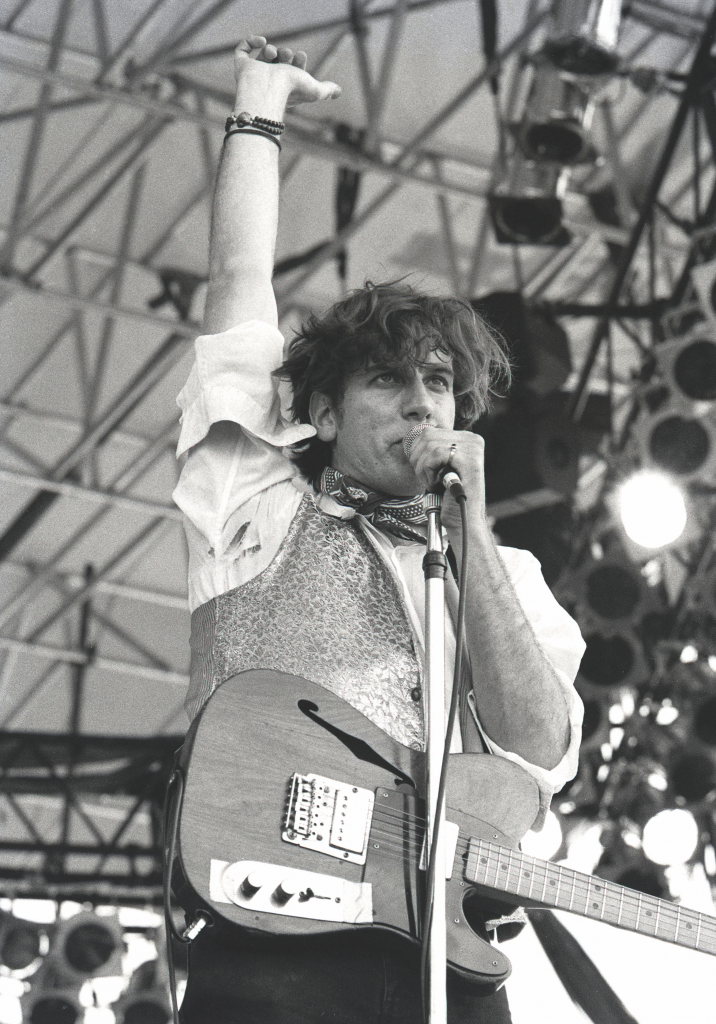

McComb was born into a wealthy[2]McComb and his brothers grew up in a grand house called ‘The Cliffe’, a well-known and architecturally significant dwelling in the Perth suburb of Peppermint Grove. See ‘Peppermint Grove, W.A. Heritage’, Federation Home, 10 September 2018, <https://federationhome.com/2018/09/10/peppermint-grove-w-a-heritage/>, accessed 28 October 2021. family in Perth in 1962, the youngest of four brothers (one of whom, Rob, would also go on to play in The Triffids). The film does not dwell overly long on his childhood, moving swiftly to the formation of the band amid the small but enthusiastic Perth punk scene of the late 1970s, McComb having been inspired by the likes of The Stooges, Television, Suicide and The Velvet Underground. The early days of the band are represented as exciting and colourful, and a true highlight of the film is the ferocious, wild energy in footage of performances from the period in which they were arguably at their peak, 1982 to 1986. The imposingly tall McComb growls and purrs into microphones with his rich baritone in these clips, his persona contrasting sharply with Australian pub-rock fare of the day.

The Triffids’ music is aesthetically unique. They are one of several antipodean bands of the 1970s and 1980s whose sound seemed to spring from nowhere (or perhaps the sky or the earth), such is the lack of any major influences or nods to any established movement or scene – other groups like this include The Go-Betweens, Split Enz, Crowded House and, to a lesser extent, The Birthday Party. What’s more, The Triffids’ song ‘Red Pony’ may be the greatest opening track on a debut album (1983’s Treeless Plain) in Australian music history: its strings, arranged by Rob McComb, swoop and soar, scything through the air ominously like a bird of prey. The film plays the song several times, as if to emphasise its foreboding mood – yet the musical highlight of Love in Bright Landscapes undoubtedly comes when a cover of ‘Tender Is the Night’, another of The Triffids’ most moving songs, plays over the closing credits.

The film suggests a couple of possible explanations as to why The Triffids were so unclassifiable: the first is that David McComb was simply a highly inventive, perhaps visionary, creative mind; the second, that Australia’s relative cultural isolation and lack of a cohesive literary or music history can’t help but breed among its artists a certain resourcefulness that leads to genuine and piercing originality. In the pre-internet age, it was one thing to be an Australian band, but quite another to be an Australian band from Perth, in terms of remoteness from the global commercial and artistic epicentres of music.[3]Since the days of The Triffids, Perth has, of course, become a hub of rock and pop, producing acts that are known worldwide such as The Sleepy Jackson, Tame Impala and the band that might be regarded as The Triffids’ spiritual offspring, The Drones.

In the film, British music journalist Mat Snow expertly articulates what made certain Australian bands seem so distinctive to UK critics, suggesting that their singular qualities emerged from a lack of complacency about art and culture – something refreshing for European audiences:

What Australians didn’t do was take for granted the stuff that we took for granted and therefore tended not to take as seriously. Australians watched art movies; Australians read poetry, read proper books by new novelists.

McComb’s own attitude to his homeland was an ambivalent one: in one interview excerpt, he says that he ‘never felt particularly Australian’; and in a letter that Pierre recites, he waxes lyrically – if a little pompously – about how

in Europe the light is not so harsh, somehow fictional, musical. Walking a Parisian boulevard, a thousand words have been written to describe every step. The air is imbued with a history unknown in Australia; every movement is wonderfully haunted in a world heavy with old pages and paint. The glare of your own innards isn’t reflected so sullenly.

The interviews with McComb that Alley has unearthed reveal an extremely photogenic and charismatic young man who, as the above quote indicates, was capable of an ornate turn of phrase. He was also armed with a sardonic nature and the capacity to direct amusing, cutting barbs against certain targets (prior to his death, he completed an art history course and moved into writing, and may well have become an accomplished literary voice had he lived). In one interview featured in the documentary, McComb lashes out at philistine audiences at early Triffids gigs, condemning the ‘private school guys having their twenty-first[s]’ as ‘the real lowest pigs’ and remarking that ‘all those guys are now in the insurance business’.

The interviews with McComb that Alley has unearthed reveal an extremely photogenic and charismatic young man who … was capable of an ornate turn of phrase.

The rest of the interviews assembled for Love in Bright Landscapes are a diverse bunch, presenting a range of different perspectives and theories on McComb’s life. On the one hand, we hear from those who shared his hedonistic lifestyle, such as early Triffids bass player and close friend Will Akers; and, on the other, from his late parents, Harold and Athel, and his long-term girlfriend Joanne Alach. Alley deserves credit for his efforts to give a rounded impression, an identity, to the ‘supporting characters’ in McComb’s life – most notably, Akers and Alach. Others who give the film heart and soul are Triffids pedal steel player Graham Lee, musician Philip Kakulas and Snow (who wrote the article for NME that earned The Triffids the British magazine’s cover in 1985[4]See Mat Snow, ‘Roses, Knives, Dead Bodies’, New Musical Express, 5 January 1985, pp. 6–7. The NME cover is a much-celebrated part of The Triffids story, in terms of proof of their standing in the UK. However, the more prestigious feather in the band’s cap was surely recording songs for the John Peel show on BBC Radio 1 in May 1985, a set later released as the EP Peel Sessions in 1987.). Also to Alley’s credit, the interviews are not uniformly positive about the film’s central figure: for instance, former Triffids manager Sally Collins at one point questions his sense of loyalty and criticises the quality of some of the band’s recordings in the late 1980s. The interviews with McComb’s elderly parents, meanwhile, are an odd presence in the narrative, as they speak about their youngest son in a peculiarly detached, almost unemotional manner.

While the sprawling nature of this film is part of its charm, there are undoubtedly interview sections and some more superfluous commentary that could have been edited out. There are also some confusing moments – particularly regarding Akers, a somewhat mysterious figure in McComb’s life. It is hinted that he played an enabling role in the latter’s experimentation with (and perhaps abuse of) drugs, and McComb’s parents state outright that he was a bad influence on their son. There is also suggestion that Akers was with McComb when he died in Melbourne in 1999 as a result of long-term heart problems[5]McComb had previously undergone a heart transplant in 1996. His heart problems take on a poetic quality when you consider that several of his songs – most notably, the famous Triffids single ‘Wide Open Road’ – feature lyrics and imagery about chests expanding, exploding and more. and heroin toxicity. At one point, musician Adam Peters – a collaborator and friend of McComb’s – says sheepishly, ominously and with a pregnant subtext, ‘Yeah, he told me about Will, yeah,’ as if to introduce discussion of some destructive or murky aspect of the pair’s relationship; but after this tantalising primer, the documentary quickly moves on to other things. This does not necessarily detract from the film – it perhaps even adds a layer of ambiguous intrigue, a bit like a McComb song – but the viewer is left with unanswered questions.

Although the almost constant presence of McComb’s music and the loving words of family and friends prevent the film from becoming too lachrymose, in the sections dealing with his final years it becomes clear that his life became dangerously unstable from about 1990, with numerous hardships and upheavals. The Triffids’ lack of significant commercial success precipitated a disjointed attempt to launch a solo career[6]McComb released one solo album, Love of Will, in 1994. after the band went on hiatus in 1989. Alongside this, his health problems worsened during this time, compounded by alcoholism and drug use. McComb’s physical transformation from smouldering leading man in the 1980s to a drained, tired figure in the 1990s is stark.

It is fascinating hearing from Alach, Collins and others about McComb’s anticipation of his transplant – specifically, the experience of waiting for a stranger to die in order to receive their heart, which we’re told McComb approached with typical dark humour. In this section, late in the film, Love in Bright Landscapes offers a deeper existential resonance, at which point the viewer might momentarily forget they are watching a rock documentary. One might recall, here, that childhood photo with the rabbits: a vivid reminder of the fragile borders between the living world and unknowable death, oblivion.

Midway through the documentary, Peters discusses the 1987 Triffids album Calenture, which he describes as ‘unlistenable’, saying, ‘I just feel pain when I hear it.’ It is unclear whether he views the album this way for personal reasons – perhaps painful memories related to its making – or is repelled by its musical direction. But for me, listening in 2021, and for many others,[7]For instance, Calenture is included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.See Robert Dimery (ed.), 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die: Revised and Updated Edition, Universe Publishing, New York, 2010, p. 579. Calenture is a delight; indeed, it features the song that first got me hooked on the band, ‘Trick of the Light’ (even if 1986’s Born Sandy Devotional rightly remains The Triffids’ most critically lauded LP). These contrasting attitudes to this album are further testament to the depth and dimensions contained within McComb’s music, qualities that will hopefully enable his work to reveal itself anew as a diverse treasure trove for each generation to come, even as time and fashion move on. Love in Bright Landscapes effectively situates the origin of that depth in the lifelong complexities and dualities at work within McComb’s mind; as such, it is a worthy salute to the man’s creative intensity – and, twenty-three years after his death, a timely reinvigoration of his considerable legacy.

https://www.loveinbrightlandscapes.com/

Endnotes

| 1 | See, for example, Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds with Shane MacGowan (Julien Temple, 2020), Slim & I (Kriv Stenders, 2020), Waiting: The Van Duren Story (Greg Carey & Wade Jackson, 2018) and Searching for Sugar Man (Malik Bendjelloul, 2012). |

|---|---|

| 2 | McComb and his brothers grew up in a grand house called ‘The Cliffe’, a well-known and architecturally significant dwelling in the Perth suburb of Peppermint Grove. See ‘Peppermint Grove, W.A. Heritage’, Federation Home, 10 September 2018, <https://federationhome.com/2018/09/10/peppermint-grove-w-a-heritage/>, accessed 28 October 2021. |

| 3 | Since the days of The Triffids, Perth has, of course, become a hub of rock and pop, producing acts that are known worldwide such as The Sleepy Jackson, Tame Impala and the band that might be regarded as The Triffids’ spiritual offspring, The Drones. |

| 4 | See Mat Snow, ‘Roses, Knives, Dead Bodies’, New Musical Express, 5 January 1985, pp. 6–7. The NME cover is a much-celebrated part of The Triffids story, in terms of proof of their standing in the UK. However, the more prestigious feather in the band’s cap was surely recording songs for the John Peel show on BBC Radio 1 in May 1985, a set later released as the EP Peel Sessions in 1987. |

| 5 | McComb had previously undergone a heart transplant in 1996. His heart problems take on a poetic quality when you consider that several of his songs – most notably, the famous Triffids single ‘Wide Open Road’ – feature lyrics and imagery about chests expanding, exploding and more. |

| 6 | McComb released one solo album, Love of Will, in 1994. |

| 7 | For instance, Calenture is included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.See Robert Dimery (ed.), 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die: Revised and Updated Edition, Universe Publishing, New York, 2010, p. 579. |