I think I was 17 when I first saw Wim Wenders’ film from 1974, Alice in the Cities. I spent an excessive amount of time in darkened cinemas in those days. Still living at home with my parents, I was already well on my way to becoming a university drop-out. What’s worse, I was a pretty lonely drop-out, and hence the darkened cinemas. At that age, at that moment in my life, I knew one sure thing about Alice in the Cities: it had been made especially for me.

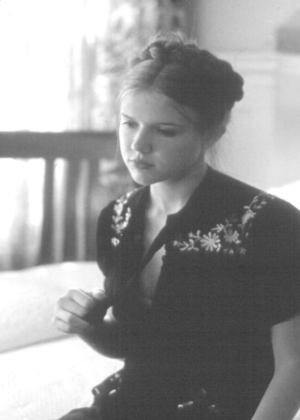

I didn’t know how time would treat Alice in the Cities, but reseeing it at last in the recent Wenders retrospective confirmed my never forgotten sense of its poignancy, its fragile beauty. Wenders, at his best, is the poet of what we might call ‘half-life’, the kind of life I was certainly living when I was 17, and that Wenders seems to have lived for an ungodly proportion of his adult years. Half-life is the withdrawn, detached, introspective, often indifferent life of the individual who simply drifts through landscapes and interpersonal situations. The characters in Alice speak of having no past or future, of having lost their secure identity in some mysterious interpersonal pile-up long ago, of not even knowing how to live. The hero, played by Rudiger Vogler, falls into an extended wandering with a young prepubescent girl, Alice; their relationship – sexless and innocent like so many of the relationships in Wenders’ films – is a testament to the ephemeral catalogue of little laughs, irritations and miracles that almost compensate for the wretched condition of an alienated half-life.

‘Alienation’ is of course one of the great cliched buzz-words of this century, but I believe that nobody captures the lived truth of contemporary alienation like Wenders. Although it might seem strange to suggest, Alice in the Cities remains one of Wenders’ most satisfying and complete films because it essentially accepts the alienated life as one that is empty, but open. To the hero’s final question, “what next?”, Alice simply shrugs and hangs out the train window, taking in the landscape.

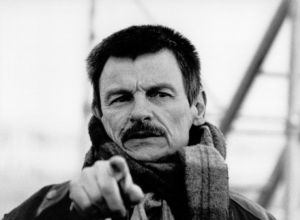

By the time of Kings of the Road in 1976 – one of the director’s most celebrated films – things are already starting to change in Wenders’ mind, and not always with great screen results. He starts pushing his characters, almost despite themselves, towards some ghostly figment of home, of Mum and Dad, of nation, and of a secure, original self. The wonderful male-buddy stars of Kings of the Road – Vogler again, and Hanns Zischler – suddenly begin to cry for their parents, or burst into existential rages, or discuss their German heritage, or vow to ‘start all over again’. A lot of this rings pretty false – Wenders trying to force a wholesome resolution where there just might not be one in sight.

For the most part, though, Kings of the Road is another extraordinary journey for Wenders and his characters – this time, a journey not only through space or place as in Alice in the Cities, but also through time: through a knotted thicket of eternally unfinished business, both personal and historical. The heroes let themselves regress: they live at the level of nonsense, of games, of the body. Wenders regresses with them as, via references to the silent cinema of Chaplin and Lang, he creates his very own ‘primitive’, almost primal cinema, unconstrained by the filmmaking laws and obligations of Hollywood.

For me, Wenders’ best films – these two, plus The State of Things (1982) and Wings of Desire (1987) – have an astonishing materiality. The light, the sounds, the saggy flesh of the actors, the extraordinary compositions of cinematographers Robbie Mueller and Henri Alekan: rarely are such formal elements granted the prominence or the eloquence they receive in a Wenders film. These things hit you because Wenders lets them hit you. His films don’t have the same timing as mainstream movies. They are slow, lingering, they concentrate on odd or excessive things. Above all, they refuse a certain kind of narrative.

It’s amazing to see that, in his very first feature, Summer in the City (1970), Wenders had already included an archetypal reflection on the evils of narrative. The super-alienated main character (Hanns Zischler again) begins to retell the story of a novel, in which a man wasting forever in prison starts, each night, to narrate the story of his life. The details of the prisoner’s account inexorably start to draw together with ritual force, they take on a direction, a forward movement, a foreseeable destiny … Zischler then avows he could not even finish the book, because it was obviously going to end in death, and immediately changes the subject.

Narrative is death: this is the equation that worries and drives experimental narrative filmmakers like Wenders, Akerman and Godard right from the 60s to the present day. Wenders gives the theme perhaps its purest expression in The State of Things: the moment the hero sets foots in bad old Hollywood, looking for money to complete his film and tie up his story, he’s a dead man, gunned down mysteriously in the street. Before this sorry conclusion, there has of course been some kind of story to The State of Things, with recognizable characters and settings. But as in much Wenders, it’s a story under no pressure to end, or go anywhere. Instead, incidents and fragments are just left alone to proliferate and resonate with each other, finding their own rhythm and tone. The same happens in the first, black and white half of Wings of Desire: the angels fly around, gathering scattered testimonies of all the world’s sad half-lives. These films might seem, at first glance, rather minimalist, thin on the ground: but in fact they possess a rich, minute, mosaic-like, crystalline form and texture, that I personally can never tire of re-experiencing.

It’s also true – as perhaps Wenders does not fully realise – that his sensibility of narrative-free, at times blissfully alienated half-life chimes in with, and perhaps depends upon, a certain apolitical approach to things. Cut loose from narrative, the Wenders hero is also excused from trying to act upon the world, excused from trying to change anything. If there’s something grandiose in Wenders, I guess it’s his tendency to project his own apolitical, drifting lifestyle onto everyone else, to take his own very particular malaise for the malaise of, first, Germany, and eventually the entire globe. Wenders is no intellectual, and his penchant for sweeping, global generalisations about the death of cinema and society, and the rebirth of art and man’s soul – the kind of generalisations that spot his features and saturate his shorter essay films – are a little short of profound. And Wenders’ love of the half-life has its unpleasant, egocentric, insensitive, awfully masculine side, too, as is all too clear in his quite obscene document of the dying director Nicholas Ray in Lightning Over Water (1980).

I think I like even less the Wenders who, in a conservative turn, wants more and more to ‘come home’ – the Wenders who places the child back in mummy’s arms at the end of Wenders on the set of Paris Texas (1984) so the male hero can wander off back into the desert to pursue his eternal male angst; the Wenders who bets all on the sublime, saving grace of heterosexual love at the close of Wings of Desire. But that’s my rational response: I can’t deny to you that, in my heart, I find the romantic resolution of Wings of Desire as sublime and stirring as it is impossible and mad.

And maybe my personal response is just one sign that, in the so-called ‘New Age’, Wim Wenders has really come into his own. His newly grandiose tales of rebirth, of the passage out of half-life and into full-life, obviously strike very deep chords in a lot of people. With a naivety and bravery that is truly disarming, Wenders is obviously going for broke with his forthcoming story of the cosmos, To the End of the World.

When Wings of Desire first premiered at the Sydney and Melbourne Film Festivals, I and all my critical friends scoffed at its lordly, humanist lament over the Berlin Wall as the marker of the ‘divided heart and soul of Germany’. But, as we’d now have to admit, Wenders was onto something. After all, that Wall did come tumbling down.