Introduction by Phoebe Pua

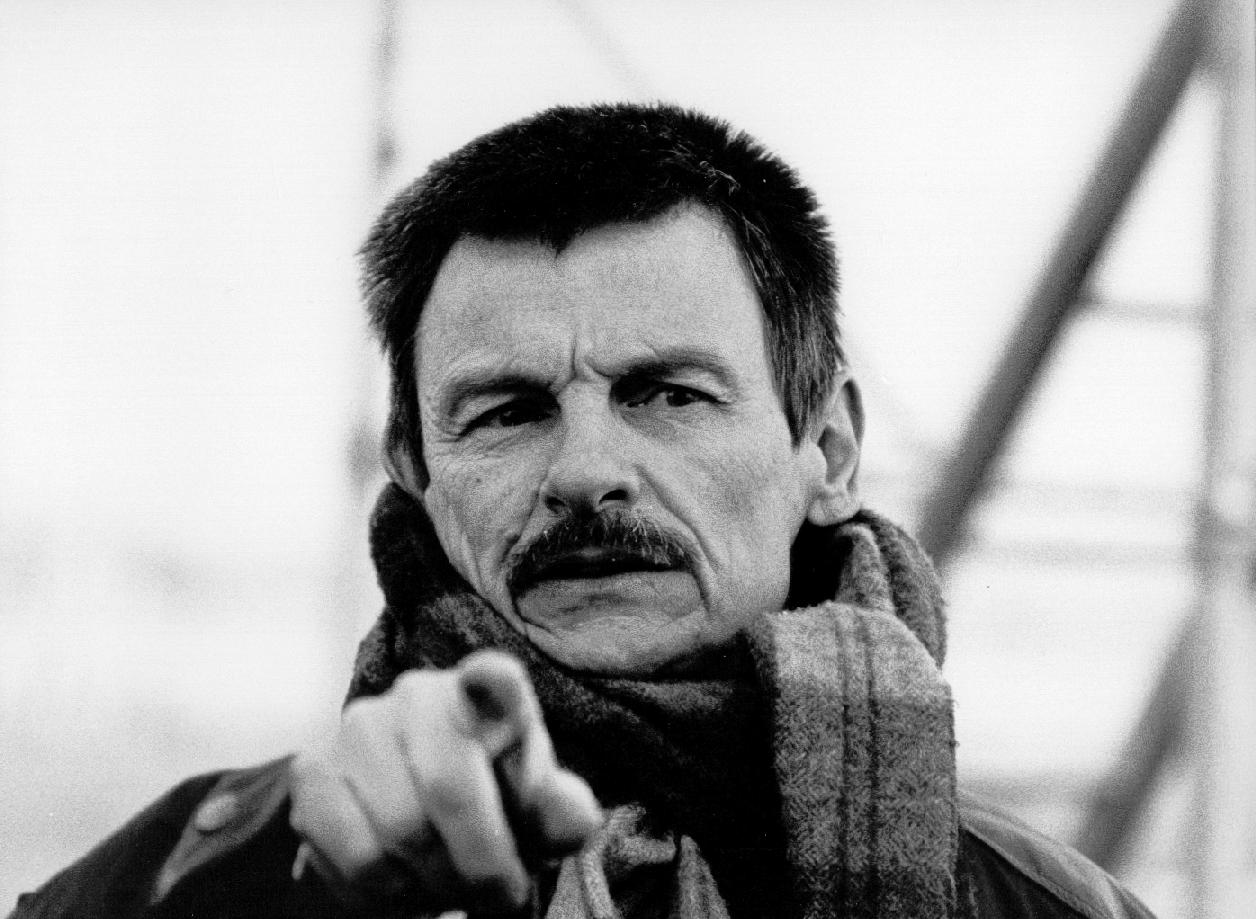

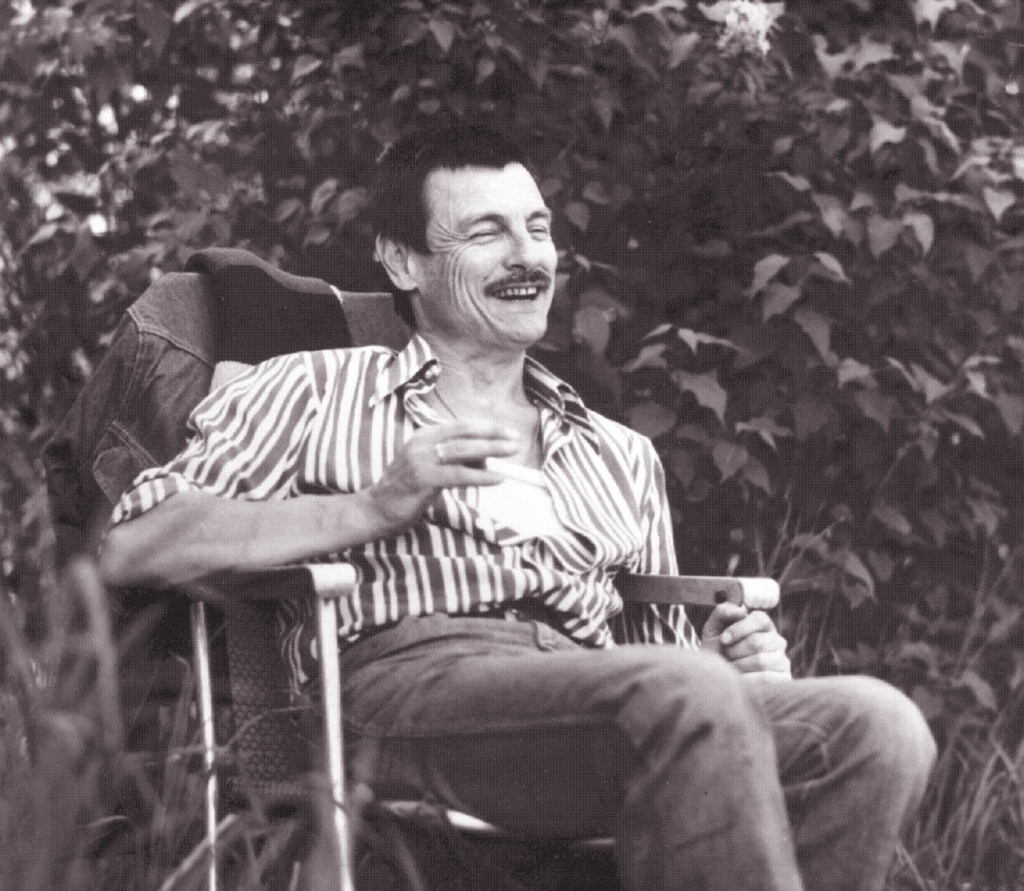

This year marks the eightieth anniversary of Andrei Tarkovsky’s birth, and fifty years since his first full-length feature, Ivan’s Childhood, was released. In his two decades as a director, Tarkovsky produced seven feature films that are today celebrated as some of the most beautiful and existentially poignant works of cinema ever made. Recognised for his audacity of form and uncompromising vision, his films read like cinematic poetry. Indeed, Tarkovsky considered himself an artist. Judging only a few others – Robert Bresson and Ingmar Bergman, for instance – to be worthy of the title ‘poets of cinema’, he aspired to elevate his craft to an art form equal to literature, music and painting. Through his films, he made profound declarations affirming the innate spirituality he saw in man.

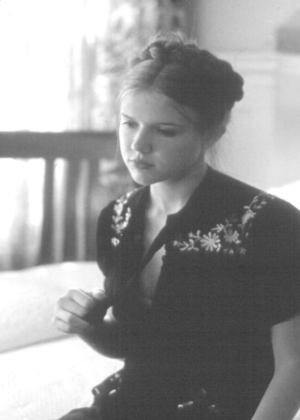

The use of the term ‘man’ here is not unintentional. Tarkovsky’s cinematic world is a deeply gendered one; his portrayals of women are surprisingly, if not disturbingly, regressive. The women of his films are limited to roles of prospective lovers, wives or mothers, all of whom are invariably dependent on the men in their lives. They exist mainly through suggestions of femininity: long tresses, pregnant wombs, dutiful subordination. Do not mistake these portrayals as misogynist, however; womanhood is celebrated, albeit only in its ‘purest’ form. Furthermore, these women are not silent, but rather possess a voice of their own; Eugenia (Domiziana Giordana), of Tarkovsky’s 1983 film, Nostalghia, comes to mind. While they are heard loudly and frequently, though, their voices only reveal that they have nothing important to say – except when they affirm their destiny as emotional centres for the men in their lives. To comfort their men, wives and lovers are expected to assume the position of mothers; Alexander (Erland Josephson) of The Sacrifice (1986) conflates his mother and his lover, calling out to the former after making love to the latter. No matter what her role, the maternal dimension qualifies the woman – she is the mother, the martyr. Anything else would be unnatural and burdensome.

To confront him on these views, Irena Brežná sat down for an interview with Tarkovsky some thirty years ago. What follows is a frank, tension-ridden conversation that marks the only time Tarkovsky publicly commented on his perspectives on women. The interview, conducted in Russian and translated here by Brežná, took place in London in 1983.

You, Mr Tarkovsky, are a privileged artist in the Soviet Union.

This idea is wrong, I think. I am not a privileged person in that country at all. A film director such as [Sergei] Bondarchuk is a privileged individual in our country, but not I.

But you are famous and that surely brings you certain advantages – perhaps disadvantages too.

This fame, this popularity you have in mind, is something I pay no attention to because it is quite uninteresting for me.

Does it not make it easier for you to work without making compromises?

True, it’s important for an artist to be sure in this way that his work has not misfired. This gives him a certain satisfaction. The fact that the public appreciates me a lot in the USSR and England, and particularly Germany, has a confirmatory value for me. It sets my mind at rest and makes me feel more confident, but it’s basically irrelevant for me.

You seem to find the limelight rather trying. You hardly give any interviews, for example.

Yes, I’m not a sociable creature. There are those who feel able to exploit their fame and enjoy contact with journalists. I was never happy with the way any interview I gave was written up. Not for any lack of compliments, but because the article usually failed to deal with what we had discussed. I always find it irritating that my popularity should make me an object of interest for anyone. It infuriates me.

Why should it do that?

Hard to say exactly. But I feel that when people meet for conversation they should have something in common so that the talk is not one-sided. When a journalist puts questions, he’s not interested in the answer he’s given, but in the answer he writes down. In so much of our activity, especially our public activity, there is a great deal of falsity, triviality and nonsense. I see no point in conversations of this kind unless I feel a need to say something myself. But since I make films, it’s in films that I try to say everything.

You are telling me that this conversation has a rather feeble starting position.

That’s always the case; it can’t be helped. What does a feeble starting position mean? We two have nothing to start from at all, except your desire to interview me and my desire to put up every possible opposition.

I can feel that very clearly.

So now let’s see how our conversation develops. I believe it was Goethe who was supposed to have said, if you want a clever answer you must ask a clever question.

You are mistaken, Mr Tarkovsky, if you think we have no common ground. I have come to see you because I feel very close to you through your films. This interview is only an excuse, as it were, for me to be able to talk to you.

You will have to give me proof of that.

I hope I can manage to. You are the only reason for my coming to London. And then I found all these obstacles in my way.

Unfortunately you’ve overcome them all. I had hoped that would foil you, like other journalists, and you would never turn up. But you’ve arrived.

Yes, I laid siege to you like a fortress and won the day. Now I am here I am at a loss for words.

Speak normally.

Well as a human being your films speak to my deepest feelings, with an insight that I feel at home with, yet as a woman I do not recognise myself in them. Women play a quite conventional role in your work. It is the man’s world that dominates; in fact there is nothing but the man’s world. Woman is seen from the man’s point of view as mysterious. She is loving – man-loving of course – and her whole existence revolves around her relationship to the man. The woman has no life of her own.

I have never given any thought to this – to a woman’s inner world, I mean. It would be hard no doubt to deny women their inner world and I would not want to. A woman has one, but it seems to me to be very closely bound up with the world of the man she is involved with. A woman on her own is in this regard something abnormal.

And a man on his own is something normal?

More normal than a man who is not on his own. That is why my films show either no women at all, or a woman who is there purely on account of a man. Only two of my films have female characters, Mirror [1975] and Solaris [1972]. And in those it is clear, of course, that the woman is in a dependent relationship to the man. Do you perhaps spurn this role for a woman?

How could I accept it? At any rate I don’t see myself in it.

Do you feel, then, that the man whose life you share should make his world dependent on yours?

Not at all. I keep my world and the man can keep his.

That’s not possible. If you retain your world and the man his, there will be nothing to keep you together. The inner world must in such cases become a shared world. Otherwise the relationship between the two people is hopeless, discordant and doomed to a slow death. It seems very odd to me when a woman changes from one man to another. It’s not a question of how many men she has belonged to, but of the principle. The point is that the woman has endured these relationships, these marriages, like so many illnesses, suffering first one and then another and so on. But love is after all such a total feeling that it can never be repeated. Where a woman can repeat the feeling it means it had no significance for her at all. Perhaps she was unlucky, or perhaps she was always trying to live in her own life – found it more important and was afraid to lose herself in someone else’s. But then she can’t expect to be taken seriously. Do you understand?

You have never known a woman who kept her own world, and felt respect for her?

I can’t stand the company of women like that.

But if I follow you, you yourself never lose yourself in a woman.

No, I have no need to. I am a man.

But you need a woman to lose herself in you.

Naturally. If a woman tries to preserve herself I must assume the relationship is a frigid one.

But you preserve yourself when you love someone?

I’m a man; I have a different nature. The whole point of feminine love, in my view, is the capacity for self-sacrifice. That is woman’s greatness. I know of no woman who demonstrated her greatness by insisting on her own world. Name me one!

I am speechless. You say, then, a woman’s only raison d’être is in loving a man.

All I said is that a person who loves cannot possibly retain a private world of their own, because this world fuses with the partner’s world and turns into something quite different. To liberate a woman from this relationship is to destroy the relationship itself. A woman cannot get up and shake herself and start a new life five minutes later. For her inner world revolves around the feelings she has towards the man, and in my view it should and must do so. Woman is the symbol of love, and love is humanity’s greatest treasure, materially and spiritually. It is woman who gives life its meaning. Not for nothing is love symbolised by the Virgin Mary – the virgin who gave birth to the Redeemer. When I speak to women about this they always talk of the feeling of dignity someone is trying to take away from them. As I see it they fail to grasp that in the relationship between the sexes they can only express their dignity through total surrender to the man.

The whole point of feminine love, in my view, is the capacity for self-sacrifice. That is woman’s greatness. I know of no woman who demonstrated her greatness by insisting on her own world.

—Andrei Tarkovsky

What do you gain from it if a woman ceases to exist as an individual and lives only through you?

I gain an understanding of her inner world and I open up to her my own.

I find that for a woman to lose herself totally in a man, as you describe, carries a great danger for the woman. If the woman seeks her road ahead through the man, she risks being left with nothing. That’s an old trap; I know it well. I have often felt a strong urge to lose myself in love.

Thank God. Be proud of it. And don’t imagine that I expect a woman to lose herself in this way. Unfortunately for me I very rarely sense this feeling of love. Love is not to be obtained by force. So my opinion is no danger to anyone. There are of course relationships where the partners become increasingly independent, and so colder towards one another and more selfish. Perhaps the going is easier then. There is of course less risk in that kind of relationship, which fits well with feminism. Some women imagine that if they can do a man’s job successfully they have won equal rights. But there is no need for women to demand equal rights with men; men and women are quite different. Women possess something of their own, something important and fundamental which men lack. Women strive for equal rights. I know what they are about. They want an end to self-sacrifice. They are convinced they have always been kept under and that equal rights will get them out of that situation. What they fail to grasp is that each of us, man or woman, is already free – if he wishes to be, of course. Each of us is a free individual, but not because he lives in a free country. That is not the point. A stonemason in ancient Rome >may have been a completely free man. Man is free in principle; if he is not free, that is his own fault. Of course, it is hard to be free. And here we are finally at the core of the matter. It makes me angry, whenever I hear people put the blame for every obstacle in their lives on others, never on themselves. If you want to be free, then be free – who is stopping you? If you are unhappy and want to be happy, then be happy. I don’t deny that over a vast stretch of time women were in a certain sense excluded from the world’s stage. That was no doubt unjust. But I am not sure what will happen to women if they become entirely part of public affairs one day. I’m not against it, I’m for it, I must stress, but I have the feeling they will not find their fulfilment there. They will find no satisfaction.

As long as male values prevail everywhere, women will find things difficult in this world – as long as her criterion is a career measured by men’s standards.

You’re wrong. I find nothing more unpleasant than a successful career woman. Not because I see any threat to my male rights, but because there is something completely unnatural about it. It’s a case of a woman choosing a path she should have simply ignored. Only a wrongheaded sense of rivalry towards men could have driven her into it. I don’t doubt that woman can succeed in any male job they care to try. Here in England a woman has fought her way through a great political career, and she is one of the most iron-hard politicians. As a politician she cuts a good figure. She annoys many people, but that is a good sign in a politician. One may dislike this woman’s role in the Falklands conflict, but then agree with her view of the Grenada invasion. There is nothing extraordinary in a woman proving she can do a man’s job. Of course she can. But that proves nothing.

What worries me in your argument is your assumption about the ‘true nature’ of woman. For me, femininity does not lie in dependence upon another individual, and that is why I cannot recognise myself in any of your film heroines. For all those women are satellites attracted to the planet Man, with no independent motion of their own.

This is very strange. I had many letters from women, even while I was still in Moscow, saying how astonished they were at my success in Mirror in seeing into their world, which they had thought to be hermetically sealed from the eyes of all outsiders. There were many of those letters. Perhaps you have a different personality structure and different needs. You are evidently not like the mother in Mirror. That film was about my own mother.

I found the treatment of love in Solaris subtle and magnificent. But for Hari [Natalya Bondarchuk] love is her only strength and at the same time her fatal Achilles heel. Love is all she has.

And you don’t want to have any Achilles heel. You want to be invulnerable.

A woman often has the dilemma of hoosing between the path of love and the path of her own personality. For a man only one path is open from the outset: that of his personality.

A woman will never beat a man on the man’s path.

Imagine for a moment you were a woman and for centuries you had been trained to exist for others and not for yourself, to be conditioned by others and not by yourself. Do you see the burden this imposes?

Do you think the man’s role is any easier?

As things are, both have a hard time.

It is as hard to remain a man as it is to remain a woman. The whole trouble lies elsewhere, in the fact that we live in a society where the spiritual level of the common man is extraordinarily low. And we all know we may go to sleep tonight and never wake up tomorrow morning. If some madman presses the button, three bombs will be enough to destroy life on our planet. It’s not that we are unaware of this, but we keep on forgetting it. Our spiritual interests are so enslaved by our material life that we concern ourselves with questions that should never have arisen for us. The emergence of social problems is the result of our lunatic anti-spirituality. It would never occur to a spiritually fulfilled woman that she is short-changed or enslaved or degraded through her relationship to a man. Just as it would never occur to a spiritually fulfilled man to make demands of a woman. I have met amazing women, amazing in their spiritual height. These women never turned such social questions into a problem; on the contrary, they themselves demonstrated such inner riches, such spiritual greatness, such moral strength that any man would fall on his knees before them and consider it an honour, not a disgrace. This is the point, you see. As soon as we try to explain our relationships there must be something amiss with us. This striving for clarification is a symptom of our discontent, not a quest for justice. A truly loving woman never puts such questions. They don’t interest her.

A truly loving woman will not restrict her love to one man, but extend it to the whole world. You were talking about the atomic danger for the world which has arisen through men’s dominion on Earth.

Though Madame Curie played a part in it.

There is no need for women to demand equal rights with men; men and women are quite different. Women possess something of their own, something important and fundamental which men lack.

—Andrei Tarkovsky

How in concrete terms can you picture a woman of today, aware of this doomsday threat, surrendering herself to sacrificial love for a single man rather than seeing herself as a creature belonging to this planet and sharing responsibility for it? Surrendering herself with the prospect that the man she loves so much, still warm from her love, will go and destroy the planet?

This is shocking, shocking. I know what you are trying to say. But I am amazed. You are quite wrong, Irena, to imagine that the man is not harrowed by the same anxiety for the world. If you believe that man is the lord of this planet you are mistaken.

And who is, then?

He is.

He – where?

[Tarkovsky points skyward.] You see the point. We are talking about results and not about reasons. This is the paramount question. Whenever men live without recognising the reason for their existence, without knowing the purpose for which [they] were born and why they are to spend their lives here for a few score years, then the world must inevitably get into the state where we find ourselves now. Ever since the Enlightenment men have been concerning themselves with things they should have ignored. They began to devote themselves to the material world. The desire for knowledge seized hold of them, especially the male sex. Women incidentally have less of this craving for knowledge than men. Luckily.

Perhaps women have a different sensory system – for knowledge of a different kind.

Precisely. So you’ve noticed that. And what was the outcome? Men began to grope around like blind people, with nothing but their hands left to find out about the world with. We have discovered so much about the world, one would have imagined we could achieve bliss and that society could attain harmony. No, on the contrary. The more we ‘know’ about the world, the more clearly the experts in these matters realise that basically we know even less than our forefathers. We are prey to fallacies. If you are blind and put your hand on a radiator that has been turned off, you think you are surrounded by a cold world. But this has no connection with the real world, only to your tactile perception. We are convinced we know a great deal about the world. We know absolutely nothing. The little particles the world is composed of, which we have some vague idea about now, give us no overall view of the world, for the world is infinite. The pathos of human existence, to my way of thinking, is not to do with achieving knowledge. That is man’s intellectual task, but not his main one. The prime existential problem is how to live with the knowledge of life’s meaning. How odd it is that we learn about the world from a pragmatic angle, one that suits our advantage. We keep making ourselves artificial limbs. The whole of our technology amounts to this. We invented airplanes because we were tired of riding on horses. We imagine we shall enrich our lives by moving around faster – an elementary mistake, quite obviously. And then we find a new source of energy by splitting the atom. And how do we use this energy? By making the atom bomb a suicide weapon. What I mean is that we are incapable of using our discoveries properly. This is because men don’t know what they are living for. The scientist thinks the purpose of life is to make discoveries, a pragmatic approach to reality. The artist by contrast lives to create works of art. They are all absorbed with their own special tasks and feel things are inequitable and envy each other. But what every human being should do is catch hold of the meaning of life and live accordingly. At that level all are right and enjoy equal rights – artists, workers, clergy, peasantry, children, dogs, men and women. If we put first things first, everything is in its right place. The crisis in our civilisation has arisen through an imbalance. There is a discord between material and spiritual development.

That began with Plato.

No, much earlier. It began when men decided to defend themselves against nature and against other men. Our society grew up from this false foundation. Men dealt with each other not in love and friendship and the need for spiritual contact but to gain advantage. Also to survive, of course. But I think man could have found another road to survival, precisely because he is human and not animal. We know a few earlier societies where men lived in harmony with nature and achieved amazing things. Those eastern cultures recorded in Sanskrit, for example, that managed to attain equilibrium between the spiritual and the material. Why did they perish, one wonders. Presumably because other cultures grew in parallel alongside and some kind of hostility arose between them, I suppose, preventing the civilisation I spoke of from developing its ideas in full. One doesn’t know. In any case, men should realise they were born into this world in order to rise above themselves spiritually, and to conquer what we call the evil in them, the evil that springs from egotism. Egotism is a sign that men do not love or understand each other, that they have a false notion of love. Hence the distortion of ideas and of everything. The idiocy and errors and disastrous consequences of modern science are not the result of women failing to take over the reins in time, but of humanity’s spiritual inadequacy. I don’t believe that spiritual development could have made men so lopsided as intellectual development has done. For spirituality includes the idea of harmony. Everything else – whatever justice there may be in your claims – is secondary. And if you failed to recognise yourself in my films, it doesn’t mean I was wrong. What I said about the women I tried to portray was true. You may not like it. But would you prefer me to portray women à la social realism?

You are prejudiced against me.

No, you’re wrong. It’s you who have a prejudice against me. I think you ought simply to ask the man you live with why he is so silly. That is how I would put it.

If that were the main issue between a man and me I should never have a chance to put the question. I should have left him before that.

Quite right. You know, we chip away at all sorts of minor problems and imagine that by solving them we can rescue the modern world from its crisis. But we are wrong. In fact I believe it is very harmful to worry about such questions since they distract us from the main aim, the struggle for spiritual strength. That is a struggle that is being fought on every front. Every spiritually mature person, even if he is completely uneducated, understands the main issue. I was living for a while recently in a village near Rome, for example. I met a farmer there who had been tilling the soil all his life. ‘If I wanted to make more money,’ this farmer said to me, ‘I should leave farming and set up a little grocery shop or something. That way I should get richer immediately. But I shall never do this.’ ‘Why not?’ I asked. ‘I couldn’t allow myself to,’ was his answer. This man had a sense of duty, you see. That showed me his spiritual strength. What keeps him running his farm and making sacrifices that benefit human society is not an eye to material advantage, but love for his work. There is a great inner beauty in that. Here are we, thoroughly nice people, and we abandon the soil without a qualm. But this farmer stood on a high moral plane. That’s why I liked him.

We are convinced we know a great deal about the world. We know absolutely nothing.

—Andrei Tarkovsky

He felt respect for the land.

Not just the land but for men and women and above all, I think, for himself. That’s the key to it. He respected himself too much to quit. He loved himself. He preserved his inner spiritual world. A man with a true sense of duty towards himself has no problems at bottom. We may try to live in an understanding of the meaning of life and in fulfilment of our duty towards life on this Earth, but we are often incapable of this. We are too weak. The trouble is that civilisation has reached an impasse today. We need time to reconstruct our society on spiritual lines, but time has run out for us. The processes that man has got going, the buttons he presses to switch on the technology, work by themselves these days. The computer has taken charge of man. To put the computer out of action requires more spiritual labour than we have time for. The only remaining hope is that at the last moment where the computer can still be switched off man will receive illumination from on high. That is the only thing that can save us.

We are forever fighting something or other and warding off some danger because the impasse is so narrow now and its cliffs threaten us. This conversation is a perfect example. You are struggling against me and I against you.

Frankly I never thought you would come. But since you are here and we have to talk, yes, people battle against the wrong enemies. Woman fights man and man woman, and men fight each other and women too. One country fights another, one group fights against missile deployment, another group against something else till we are all fighting each other, instead of struggling against ourselves. For we are our own worst enemies. That is where the struggle must begin. I too am my own worst enemy and I am always wondering whether I shall win the battle against myself or not.

I am particularly interested in your latest film, Nostalghia. Were you concerned there with the problems of emigrant life?

No, its not an emigration film, it’s a film about nostalgia, about the feeling of homesickness for your own country. That’s all it’s about.

What do you regard as your homeland?

Home is the country where you were born and grew up, with whose culture and roots you are connected. I stayed for some time in the USA and the country astonished me – a land without roots. Its rootlessness is so obvious. This makes it so dynamic on the one hand, so free of prejudice – yet on the other there is this lack of spirituality. People start a new life in a new place and cut their ties with the past. This is altogether a very fertile theme; it was in America that I found the idea I had treated in Nostalghia confirmed. It’s incredibly hard to live that kind of life. When one steps out of the historic process all the problems begin. That’s what the film is about. How can anyone live a full and normal life if he has cut loose from his own roots? In Russian the word ‘nostalghia’ implies a sickness, a mortally dangerous one.

It’s very tempting to cut loose from everything.

Tempting? True enough.

And it means an opportunity, too.

No, no opportunity.

None?

None. No opportunity lies that way, Irena.

An opportunity for individualism?

That’s another thing men are not yet ready for.

I think of our century as a nomadic one, with more and more intermixing of races. We are increasingly emigrants. Perhaps after a few more centuries we shall manage to overcome the nostalgia.

That must of course happen in time. But the problem is in principle a deeper one. And you probably won’t disagree if I call it an abnormal state of affairs for the globe to be split between two spheres of influence. It’s abnormal because it was not man who made this Earth. Man is not entitled to it. He is only entitled to live on it and grow up spiritually, not to divide the world with barbed wire and defend that division with atom bombs. This is inhuman activity. The same situation by and large has brought the other problems: nostalgia, civilisation and confrontation. What else could such behaviour lead to? If I am convinced that I am right and my neighbour wrong, if I am completely at odds with him and not even willing to have reasonable dealings with him, it’ll end up sooner or later in open confrontation. Inevitably. We live inhuman lives. Nostalghia is a film about the question of how to live, how to find some way to agree in this divided world. This could only happen if there are sacrifices on both sides. A man who is unable to make sacrifices has nothing to expect.

Are you able yourself to make sacrifices?

Hard to say. I am just as incapable of it as other people. But I hope to become capable of it. I must hope so, for if I die without proving to myself that I have the ability it will be a sad business.

And how will you achieve it?

How? I don’t know. By doing or striving towards what I think is needed for living as one should live. But my profession is a hindrance. I am not sure that what I do in my profession is really necessary, or whether I ought to go on with it.

What would you like to be doing?

Sometimes my work for the cinema strikes me as ridiculous. And it is really ridiculous; there are much more important things. How to tackle these things, how to find one’s own self in them, whether art offers a positive way forward at all – that’s the question. This is what one teaches other people, but one isn’t prepared oneself: this is what tortures me. Perhaps these thoughts are excessively Russian. These were the questions that bothered Leo Tolstoy, for example, and they made his whole life miserable.

How are the various stages of your personal development mirrored in your films?

I would say my films do reflect me, no doubt of it. Whether they show any development it’s not for me to judge. I just couldn’t make films without bringing my own personality into them.

If I compare your different films I get the impression you are working towards an ascetic style.

Yes, that’s true. I would like it to be so. My last film expressed everything simply enough, I believe, not in such a complicated way as the earlier films. One can never please you people, the filmgoers. Whatever you do there are always millions of questions. I am not sure of anything any more.

Do you think about the filmgoer at all?

I have never thought about him. How could I? What is he to me? Am I to teach him lessons? Have I any means of knowing what John Smith thinks here in London, or some Vasil Ivanov in Moscow? I should have to be a complete hypocrite to claim to know the thoughts, the inner world, of another person. If I want to create anything at all I can only put it in my own language, treating the public as an equal partner. If I am puzzled about anything I assume the public is equally puzzled and try to use my film to clear it up for myself and for the public at the same time. I am neither more stupid nor more intelligent than the public. My own dignity is as vulnerable as theirs. Of course, you can make films with an eye on the filmgoer’s pocket – nothing easier. But that’s not my vocation.

How does it feel to work creatively in a foreign country and a foreign atmosphere, to have to deal with people whose mentality is after all one you cannot get close to?

I made Nostalghia abroad. I think it makes no difference really.

The Czech director Milos Forman has been shooting films in America as an emigrant since 1968. He said once that in the Eastern Bloc you have ideological pressure and in the West the artist is hampered by commercial pressures. What say you?

Yes, I do sense a strong commercial pressure here. But I’m not capable of making films subject to anyone else’s wishes.

Can you really avoid making any compromises?

I don’t think I can manage compromises or accept any at all in my work. That’s why it makes no difference to me where I do my work. If anyone gives me orders I know I shan’t carry them out. I can’t turn out anything that is not my own idea. There are of course huge obstacles.

Your father Arseny Tarkovsky is a famous modern lyric poet in Russia. His medium, poetry, is a timeless one. Yours, the screen, is more vulnerable to time. How does it affect you, this closeness to someone with the same name?

Not at all. I don’t agree with you, because in art there is no distinction between superior and inferior branches. Quality is all that matters. There is good and bad poetry, good and bad films.