André Téchiné’s dynamic films, which have the intuitive smarts of a darting cormorant or a good volleyball spike-man, constantly flip between extremes: lithe and tough, critical and romantic, harsh and celebratory, interior and exterior. His storytelling is as rhythmically varied and surprising as a piece by Varèse – a welcome contrast to most of modern cinema, both independent and studio, which lumbers forward with the plodding beat and methodical impersonality of an Abba song. Directors all over the spectrum now design their films with boring efficiency at every stage of the game and most movies, from 800-lb. gorillas like Independence Day (1996) to little nosegays like Flirting With Disaster (1996), are set pieces stacked on top of one another without a governing idea; conversely, characters are shackled to a non-stop, single-speed forward motion for fear of diverting attention from the predictable succession of thrill effects. Even a good, provocative film like Safe (1994) is marred by Todd Haynes’ inability to imagine anything livelier for his heroine than a cliched notion of the alienated California housewife – it’s ironic that a film about the ambiguities and cruelties perpetrated around environmental illness is directed by such a neat freak. This kind of cop-out linearity is anathema to Téchiné, the most questing, restlessly curious figure in modern movies.

Any Téchiné film is motivated by equal measures of intellectual and emotional drive. Lazy critics who are used to either one or the other, but never both at once, reject him out of hand, but in his movies the brain and the body are like a cog and lever that run the whole system. Except for the autobiographical Les roseaux sauvages (The Wild Reeds, 1994), his major work splits into three groups: melodramas that build their stories around the social networks of culturally impoverished towns (Hôtel des Amériques and Les innocents); sinewy portraits of ambitious young provincial types who get a sentimental education in a nocturnal Paris (Rendez-vous and J’embrasse pas); and chamber works that dive headlong into the turmoil of a bourgeois family in a state of emergency (Le lieu du crime and Ma saison préférée – his newest film, Les voleurs, actually synthesizes all three tendencies into a dizzying/sobering Faulkneresque whole). Téchiné has an acute understanding of the way things work in modern society and a Brechtian desire to lay it out as cleanly as possible, but he sticks close to the psyches of his neurotics and loners and his narrative structures chart every twist and turn of their zigzagging progress. You don’t come out of his films remembering scenes but illuminating bursts of insight that have the feel of winning cards slapped on a tabletop. Just as a good singer doesn’t bend his/her notes for effect, Téchiné never lingers on emotional exchanges: his universe is all impulses and sudden decisions. In a typical Téchiné scenario, a character hyped up with resolve lands in a crisis situation in which his/her settled image of the world clashes with the flux of reality. It’s the exact opposite of all the goal-oriented pap of the moment: here the goals are turned inside out and broken up by life’s contingencies. This is an unsentimental vision of people that’s truly compassionate in its rigorous clarity.

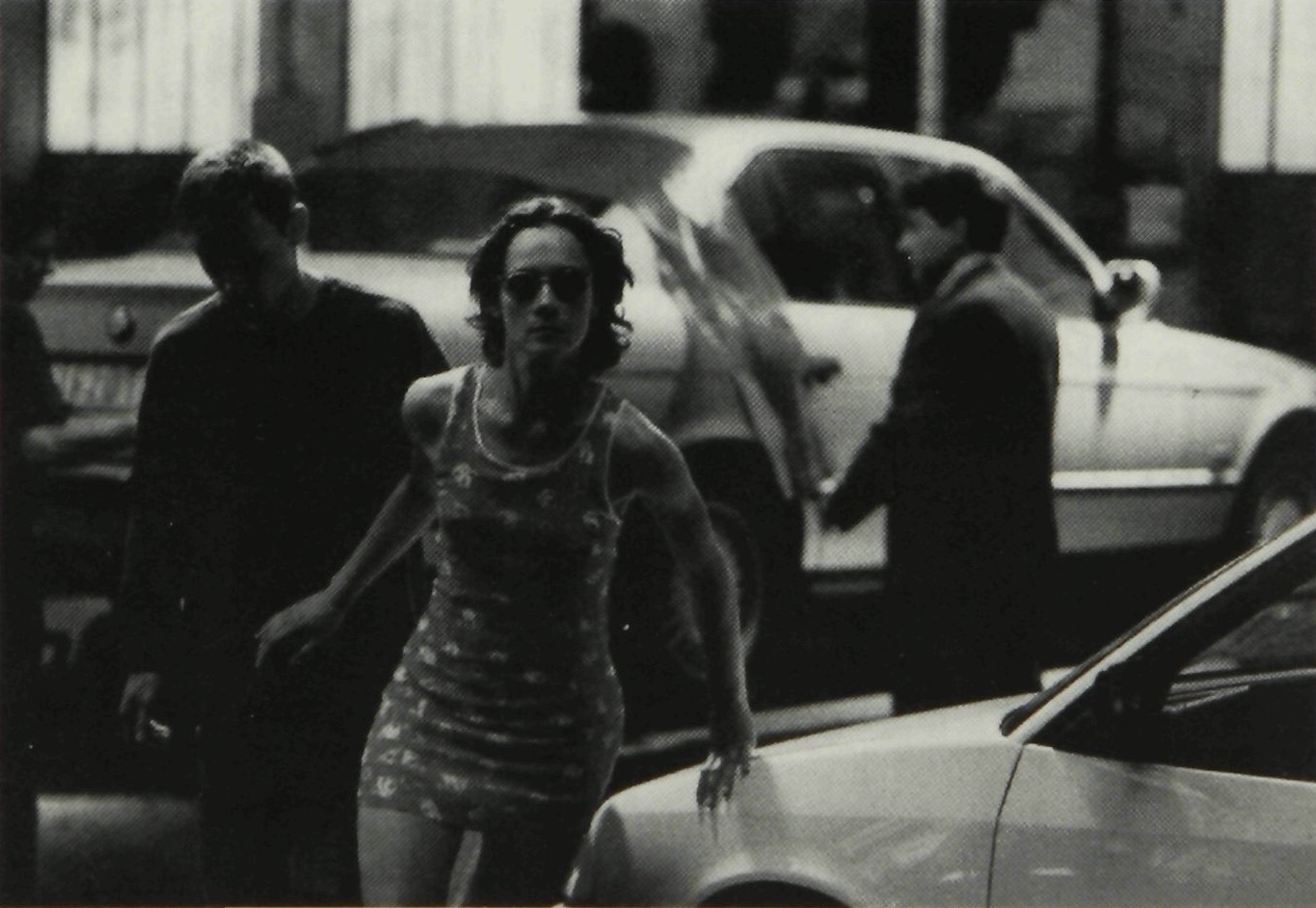

His 1991 J’embrasse pas (I Don’t Kiss), by his own admission his most straightforward film, is also his most unsparing. A cocky kid named Pierre (Manuel Blanc) leaves the Loire Valley to take Paris by storm. Acting class is too daunting a challenge to his ego, and after a haltingly stiff monologue reading – shot in agonizing close-up – he runs out of class for good and throws his copy of Hamlet into the Seine. Out of impatience, hard luck and the lure of quick cash, he finally settles for star status as a Bois de Boulogne hustler. Téchiné’s strongest suit is his deep-kissing intimacy with his actors, filtered through his narrative gifts and balanced compositional eye (along with John Carpenter, he’s probably the only modern master of Scope). The young Blanc’s quicksilver smile, his most arresting trait as an actor, is pressed into service as the film’s visual touchstone. In a brilliantly compacted scene, he offers to sleep for free with the off-handedly ominous Romain (Philippe Noiret) in return for ushering him into a world of material splendour. As Romain dismantles his freshly minted personality, Pierre desperately pushes his seductive smile to the breaking point. Later, this haughty street-star who doesn’t kiss gets an unspeakable comeuppance when the irate pimp of a hooker on whom he’s fixated (Emmanuelle Béart) takes him to a railroad siding and rapes him.

J’embrasse pas comes off at first glance like a taut bildungsroman, but at its core is the unsettling proposition that ambition, sexuality and identity are completely mutable. Pierre isn’t receiving an education but pushing himself into a combustible situation in which his sexuality is transformed. The film lurches with Blanc’s bursts of energy, meant to displace his homosexual predilections but which instead rocket him further into brutal recognition. Whether he is a latent homosexual before he arrives in the city (‘He goes to Paris like he’s going to Mars,’ Téchiné told me) or whether his sexuality is shaped by circumstances is immaterial. It’s only the action of the moment that counts, and Blanc’s seductive smile is the poignant symbol of that hard-nosed philosophy.

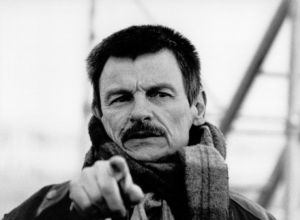

Téchiné has one of the most unusual career trajectories in movies, as surprising as one of his own films. He grew up in the south of France, the area of the country where he has filmed most often, and was a cinéphile from an early age (Les roseaux sauvages begins with the young hero suggesting to his friend that they skip the wedding they’re on their way to and see Ingmar Bergman’s Through a Glass Darkly, 1961, instead). After a mid-’60s stint as a critic for Cahiers du cinéma and assistantships to Jacques Rivette on L’amour fou (1968) and theatre director Marc O on his film Les idoles (1967), Téchiné jumped into filmmaking with a little-seen feature-length psychodrama called Paulina s’en va (Pauline Leaves, 1969). His subsequent ’70s work has its admirers – the futuristic neo-noir Barocco (1976); the painterly, all-star Les soeurs Brontë (The Bronte Sisters, 1979, complete with a guest appearance by Téchiné’s close friend Roland Barthes as Thackeray); and the brilliantly flamboyant 20th-century Brechtian pocket saga Souvenirs d’en France (French Provincial, 1974). But in the ’80s, Téchiné rejected the delirious cinephilia of those films and shook his aesthetic inside out. The stylization ended with Les soeurs Brontë, because at that moment I had the feeling that I had gone as far as I could experimenting in that direction,’ Téchiné commented in Laurent Perrin’s 1994 documentary Andre Téchiné: Après la Nouvelle Vague. ‘I wanted to interest myself less in cinema and more in people … Quite simply, I think that when I was young I didn’t know people at all, certainly less than I do now. I couldn’t have done otherwise: it was both a natural evolution and a conscious decision.’

‘It’s above all the way of filming the faces and bodies of actors that changed with Hôtel des Amériques, and then also the way of looking at the outside world, allowing little traces of things, of the real, into the film.’ The change is so complete that Hôtel des Amériques (1981) could be the work of a different director. The heavy, corseted performance style of Barocco and Les soeurs Brontë gives way to the mobile, three dimensional approach of Hôtel, in which actors are allowed to define the contours of their own roles. Compared to the lock-step procession of academic vistas in the earlier films (with the exception of the rhapsodic 16mm Souvenirs), space in Hôtel is exploratory, forgoing the obviously picturesque in favour of a commitment to mapping out the social, psychic and physical layout of a washed-up resort town.

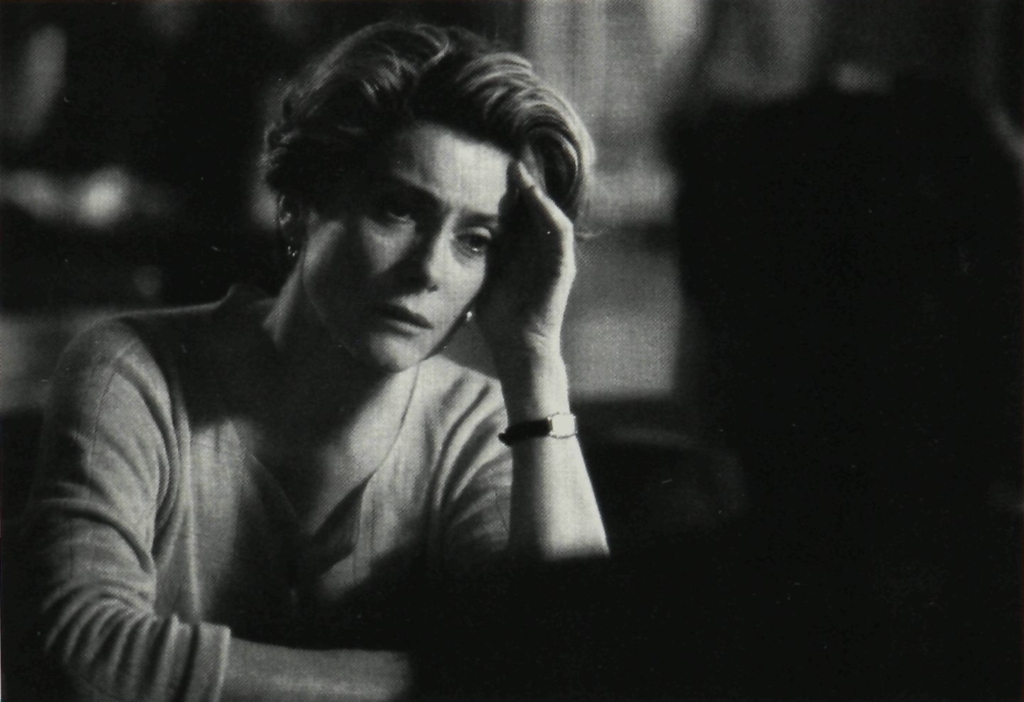

In Hôtel des Amériques, a collection of fragile, static people is ensconced in dilapidated, modern-day Biarritz, and they lack the ambition to leave. Everything in this ‘melodrama’, including the love affair between layabout Patrick Dewaere and anesthesiologist Catherine Deneuve (the first film in a long collaboration with Téchiné – he’s the only director who can destabilize her leonine poise), is oriented around the phantom ego-building that goes on in failing towns. Its actors are photographed with a heightened, erotic glamour, but Hôtel stays very life-sized in its concentration on people wandering in a fog of pastness and unhealthy security. It may sound pithy but there is a real sense in which, from Hôtel des Amériques onward, Téchiné crosses Hitchcock’s precise visualization with Cassavetes’ emotional field journeys and findings.

‘I have a taste for obscure, solitary characters, forever in the shadows,’ Téchiné admitted in a Cahiers du cinéma interview, and Etienne Chicot as Dewaere’s friend Bernard in Hôtel des Amériques is the prime example. An unkempt singer/songwriter forever putting the finishing touches on his masterpiece and dreaming of instant paydirt in New York, his action consists of needling people from behind a mask of superiority. He reflexively insults the classy Deneuve for no reason other than the fact that she is classy, and beats up a guy who makes advances to him in a men’s room after tentatively coming on to him in the first place. Chicot’s soft, paunchy body, his sandy hair and self-hating drone walk are indelible: they speak eloquently of bereft, unfashionable places where the inhabitants desperately inflate their fantasies into permanent mobile shelters.

Each film is as keyed to physical and personality types as J’embrasse pas is to Pierre/Blanc and Hôtel is to Bernard/Chicot. In fact, a lot of the beauty of this director’s oeuvre is in the remarkably varied gallery of physiques he’s put on film (a stark contrast to the most sluggishly predictable aspect of modern cinema, the uniformity of health club bodies). Téchiné is given to describing actors in almost erotic terms (‘What I like about Wadeck Stanczak is his stocky body which contrasts with his very pure, very angelic fresh face,’ he told Cahiers), and his films sparkle with human energies. Serge (Stéphane Rideau), a handsome, hulking teenager in Les roseaux sauvages, suggests a teenage version of Of Mice and Men‘s Lenny. Roseaux, a sexual and political coming-of-age story set in 1962 at the climax of the Algerian war, is a magical assemblage of odd, individual styles of comportment. Besides the gentle lug Serge there’s the purposeful Maité (Elodie Bouchez) with her brusque shoulders-forward walk and unconsciously delicate way of turning her head; Henri (Frédéric Gorny), a cool, stoic, pied noir (French-Algerian) with a severe grace that seems half-studied, half-natural; and François (Gaël Morel), the skittish, sweet-faced hero who moves with a fleeting breathlessness. This vain, romantic soul-searcher, a beautiful self-portrait of the director, has a light step and young aesthete’s fragile intentness that are just right.

‘You have to know how to look at each actor for himself and try to engage his singularity,’ Téchiné once told Cahiers. His actors are his guiding lights, and the films record them in a succession of romantically, almost hieratically-lit states of being as discrete and precise as in a Muybridge study. Each actor is allowed to find his or her physical mein before their director sets them off in high gear. There’s always an erotic charge between Téchiné’s camera and his performers – because the edits jump on their movements, they often enter a scene as though they’ve been shot out of a cannon: when the recently awakened coma victim played by Simon de la Brosse makes his first appearance in the 1988 Les innocents, every nerve ending on his body seems to be meeting the air for the first time and at high velocity. ‘When people speak to me about my direction of actors they think they’re paying me a compliment, but it’s a myth and everybody should know that by now,’ he said to Cahiers. ‘The director is behind the camera and his risks are happening elsewhere: he’s never out there. I’m always afraid for actors. I content myself with assisting them as I would people in danger.’ As a director, he is obsessed with pinning down the singularity of each action and at the same time maintaining an uninterrupted behavioural flow, and he has found working with two cameras (a practice he began with La matiouette, a beautiful 1984 short film that he shot for television) the best way to get around the inherent contradiction. ‘Everything I do is meant to introduce disorder into the process. Therefore, I shoot more and more with two cameras in order to avoid excessively static compositions … the disorder is conceived in the hope that something new will loom on the horizon.’

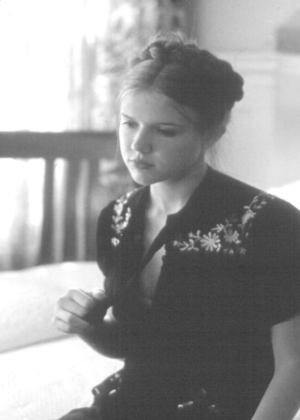

The 1985 Rendez-vous is the open sesame to Téchiné’s oeuvre. Juliette Binoche (in the film that made her a star) plays Nina, another provincial neophyte ‘with her head in the clouds’, as Téchiné puts it, who makes the journey to Paris. The gawky ingenue entangles herself with a trio of unbalanced men: an aggressively sweet fellow named Paulot (Stanczak), a wasted, tragically handsome actor and sex club performer named Quentin (Lambert Wilson), and a middle-aged director named Scrutzler (Jean-Louis Trintignant) who mysteriously appears after Quentin commits suicide. Rendez-vous evolves into a series of harsh encounters and phantom doublings. Scrutzler casts Nina in a production of Romeo and Juliet in which Quentin was to play Romeo, and she is haunted to the point of hysteria: by Paulot with his angry, impatient lust, literally by the leering wastrel Quentin (his ghost slams Nina into the wall and tells her she’ll make a shitty Juliet), and by her own self-doubt. Trintignant’s Scrutzler looks more like an apparition than anyone else and seems to be exploiting Nina for diabolical purposes but instead proves to be her dark angel – he pushes her out onto the stage and into the terrifying uncertainty she’s been trying to avoid. The final image – a pan from Nina waiting tearfully in the wings, past the musicians playing the overture, to the stage and the shadow of the curtain opening – is the most concise expression of Techine’s career theme: to paraphrase the biblical quote before the final credit roll, ‘part of you must die if you’re going to live’.

Very often, the closer and more precise a filmmaker gets in the expression of his or her ‘worldview’, the less exciting the film. Rendez-vous has a shapely dramatic structure (which probably comes courtesy of co-writer Olivier Assayas, whose own brilliant cinema renders disorder from a different and more unsettling perspective) and uniformly dark visual scheme that are uncharacteristic: its perfection and consistency operate at the expense of the trip-wire precariousness that makes Téchiné’s other post-Hôtel films so thrilling. In fact, the film might be one of the reasons he’s so often incorrectly tagged as a lyrical neo-classicist. ‘In my case the scenario is just a jumping off point, but it’s a necessary stage because unlike other directors I don’t have the courage to start from nothing,’ he told Perrin. ‘What I need from the scenario is not just to find the story but to lay down a certain pattern for my characters.’ Les innocents, an unsuccessful but gripping film, strikes off in a thousand bold directions at once (Hôtel‘s boredom in a small seaport, racism, sexuality as weapon, a journey of self-discovery): here there is a whole gallery of down-and-outers like Chicot’s Bernard and Trintignant’s Scrutzler, and the escalation of themes and characters finally gets as busy as an intersection on the LA freeway. Perhaps the film’s principal failure is an inert Sandrine Bonnaire (stepping into a part written for Binoche), whose slow-burning emotionalism is a world away from Téchiné’s flash-fire illuminations. But despite its ranginess, Les innocents has a sharp intuition for the way tensions of all varieties slowly percolate in arid coastal towns resentful of African immigrants.

Similarly, Le lieu du crime (Scene of the Crime, 1986) doesn’t really manage to sell one of its central plot points: that Lili (Deneuve), a dissatisfied bourgeoise, willingly goes to bed with Martin (Stanczak), who has committed a murder witnessed by her troublemaking son Thomas (Nicolas Giraudi). Even so, this story of a ‘bad mother and a bad son’ transgressing the neurotically normalizing influences of a status quo household might be the director’s most pungent work. Le lieu du crime digs into Thomas and Lili’s tortuous bond with an amazing focus and density. The mean, fucked-up mother and son display real vitality in their deep dissatisfaction while the priest/father/grandmother triumvirate are dead in their kindly moral certitude. Téchiné’s never filmed his Agénois birthplace more excitingly than in this film, in which quick, nervy inflections of pastoralism – ecstatic long views of the hilly Auxvillars landscape in burning autumn colours doubling for summer – both counterpoint and amplify the extreme melodramatic situation.

The point is that a modern film director who doesn’t strait-jacket himself with an ideal of perfection is so rare as to seem unearthly. ‘I don’t make a film imagining myself under the tutelage of some director I admire. I work intuitively,’ he told Cahiers. Arguably, with the exception of Les voleurs, each movie overreaches in some way: besides Crime and Innocents, Les roseaux sauvages gets giddily dense with narrative incident and too telescoped in its second half; J’embrasse pas has some interactions between Pierre and Béart’s hooker that enlarge the scope of the film but go a little flat. But this overreaching takes the films to places they would never have found otherwise, and Téchiné makes something alive with each new movie. For him, the constant process of discovery is everything, and very often he goes back and refines something that hasn’t worked in a previous film. The entire second half of his career is a corrective to the first, and one of the reasons he did Roseaux was that he felt the scenes with the younger people were unsatisfactory in Ma saison préférée (My Favourite Season, 1993).

Ma saison resonates with Téchiné’s intuitions: it’s filled with odd tics and obsessions that echo across generations of people who obstinately insist that they don’t relate to one another on any level. An aging woman named Berthe (Marthe Villalonga) talks to herself for comfort, while her live-wire son Antoine (Daniel Auteuil) does the same to summon up courage. Berthe’s granddaughter Anne (the luminous Chiara Mastroianni) longs for a sister, while Antoine longs to have his own sister Emilie (Deneuve, Mastroianni’s mother in the film and in real life) close to him again, as though their childhood will extend to infinity. Berthe has a delirious vision of Antoine in an accident, a ‘prophecy’ he later fulfils by awkwardly jumping from a second storey window as a guilt-inducing tactic, managing only to break a leg. ‘The most moving achievement of Ma saison préférée is that it films the undefinable space between childhood and old age, between living – the wound – and becoming – terror,’ wrote Camile Taboulay in Cahiers. The parallel to Cassavetes is especially apt here. That ‘undefinable’ space is built out of duration and repetition in Love Streams (1984) and A Woman Under the Influence (1974) while Téchiné does it here with an accumulation of narrative and physical detail. The past is deftly mingled with the present: sudden cuts or dissolves to old photographs, subtle insertions of expressionism (as Antoine drives Berthe home after a fight with Emilie and her husband Bruno, every light on the highway whites out the screen in a resounding echo of his family-induced vertigo), and the most delicate use of sound and atmosphere.

The film builds a criss-crossing network of faux-pas, little bursts of joy, poignant frissons and awkward cruelties that reaches its maximum density in a final movement that’s a reminder of how lazily imagined most current movies are. There’s no transcendence or sudden understanding after Berthe, a moody, judgemental woman, dies a lonely death in the hospital (a quick sequence of brutal honesty: a life support machine starts humming and the lines go flat, a nurse walks into the room and disconnects some tubes, tosses something into an empty metal garbage can, flicks off some switches and walks out – time doesn’t slow down to allow for even a moment of enlightenment). The sense of loss is odd, like hitting a funny bone. At the funeral, Anne complains about what a bitch she was. There are emotional connections amongst the mourners – fleeting, wary. They eventually find themselves seated around a table, awkwardly taciturn until Anne asks everyone, ‘What’s your favourite season?’ Each person describes their own favourite, an inexplicably moving moment: it has something to do with the film’s powerful sense of lush summer ripeness, but it’s also a perfect coda for a movie that envisions life as an entropic field of time in which the living become hopelessly lost. After the trauma of family confrontation and the horrors of committing a parent to a nursing home and watching her deteriorate before your eyes, of death and its reminder of mortality, everyone remains the same. Imperfections stay intact, no one has learned a lesson, but something has been revealed: the deep, churning energy of familial feeling, neutral on its own but liable to flip from hatred to tenderness and back again within a second.

Without an ounce of editorializing, Téchiné manages a remarkable portrait of bourgeois family life here. On her deathbed, Berthe tells Antoine and Emilie that their father wanted them to be ‘modern’. The word speaks volumes: she’s an illiterate farm widow who has pushed her children to be overachievers, because she’s wanted the best for them, and best means ‘modern’: urban, bourgeois, disconnected (earlier in the film this same modernity has been the subject of her abrasive scorn – ‘Why do you live in such a big, pretentious house?’ she asks Emilie). The miracle of this exchange – an extraordinary blending of Villalonga’s tight lips and beady eyes, Auteuil’s kamikaze eagerness and Deneuve’s deer-in-the-headlights helplessness – is that it’s a sudden, stabbing pain and then it’s over. Most directors are too addicted to the miracles of Sudden Recognition and Capacity For Change to let the fleeting nature of life, realized in those moments when existence is its own private planet floating in endless space, reveal itself the way it does here.

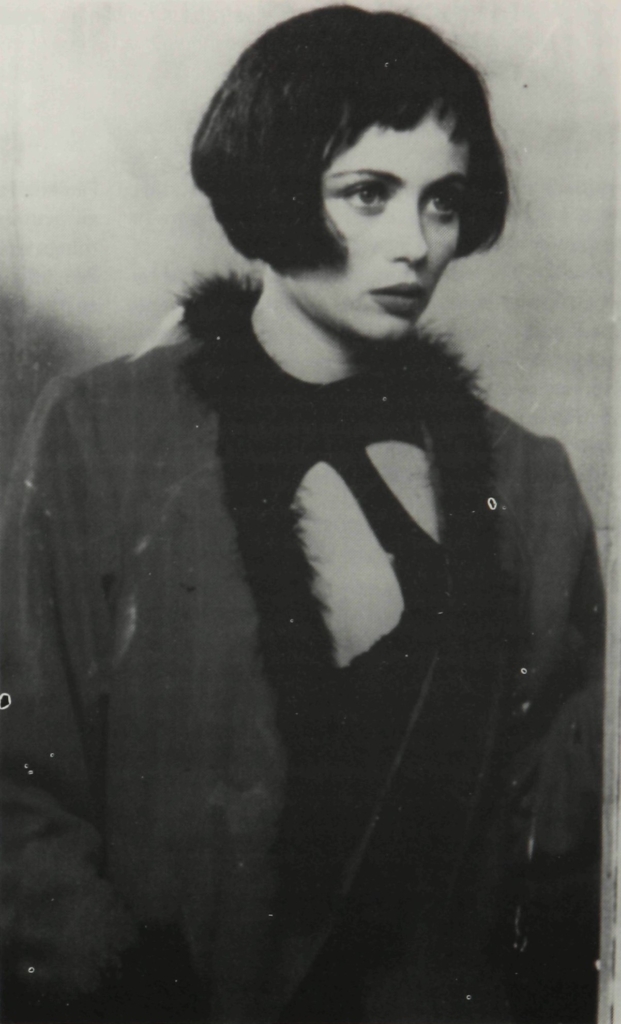

‘Olivier Assayas told me that it was an adaptation of a non-existent Faulkner novel,’ Téchiné said of the script for Les voleurs, and while the criss-crossing time frames and breathlessly shifting points of view are reminiscent of the director’s most cherished author, this film has its own unique, rock-solid vision. The story works as a chain in which the first link is a tough little boy (Benoit Magimel) and works its way back and forth in time around events before and after the murder of his father, a petty car thief (Didier Bezace). The film is alternately narrated by the boy; his uncle, a cop and therefore the black sheep of the family (Auteuil, more tightly coiled than in Ma saison and more secretly compassionate); a nervy, hell-bent girl (Laurence Côte, a fetish actress for Jean-Luc Godard and Jacques Rivette who explodes out of her thin skin and lanky frame here) who is mixed up with the gangster and who sleeps recreationally with the cop; and a brainy, oddly-fragile professor of philosophy (Deneuve) who has unaccountably fallen in love with this girl in her middle age. Téchiné is even gutsier than usual here, hiding his connective tissue by jumping in and out of a variety of site-specific situations (a tense and nervously fast brother-to-brother confrontation in a gangster-owned gay disco; an explosion of suicidal frenzy in a dingy police station; an astonishing sequence in which Bezace’s gang tries to heist a trailer full of cars by a railroad siding that becomes hypnotic with absorbed gestures and the high, hollow sound of trains being shuttled in the distance) with a dextrousness that becomes truly majestic by film’s end. There’s still not an ounce of fat or a trace of audience-winking in Les voleurs, which is miraculous given its breadth. The restless shuttling back and forth between characters making blind, impulsive stabs at connection disguised as retreating measures creates the odd (and much sought after) effect of one lonely, universal being. The exact opposite of the stately Roseaux sauvages (the final section of that film is rapturous but unusually rhetorical: rushing water! sun-dappled adolescents! the passing of time!), Les voleurs finally becomes profoundly moving but remains as tough as nails.

Téchiné is as singular an artist as we’ve had in the cinema: a Brechtian who actually understands the passion and violence in Brecht (a rarity) with a novelistic sense of story, a musical sense of rhythm and a filmic feeling for the beauty of people in motion. His devotional commitment to the specificity of human experience puts him more and more in the tradition of tough, locked-alignment artists like Piero della Francesca, Anton Webern and Robert Bresson, and it’s probably the main reason for his relative invisibility outside of France. It’s funny that this nervous, chain-smoking aesthete makes films that betray the presence of ‘a Buddhist in turbulence,’ as Henri Cartier-Bresson’s wife described her husband in a recent magazine profile. Téchiné’s work is built on the acceptance of a neurotic Western dynamism, the better to portray life with clarity. He works hard to achieve understanding rather than easy pathos or needless complexity. Andre Téchiné may not be comfortable in everyday life, but somehow he brings the ‘grain of zen’ to his work that the late Gilles Deleuze once prescribed for western living. For my own part, Téchiné is one of the few artists alive who teach me not about art or film but about life, and the distinction between the hardened images in our heads and the slippery indifference of reality. For that I treasure him.