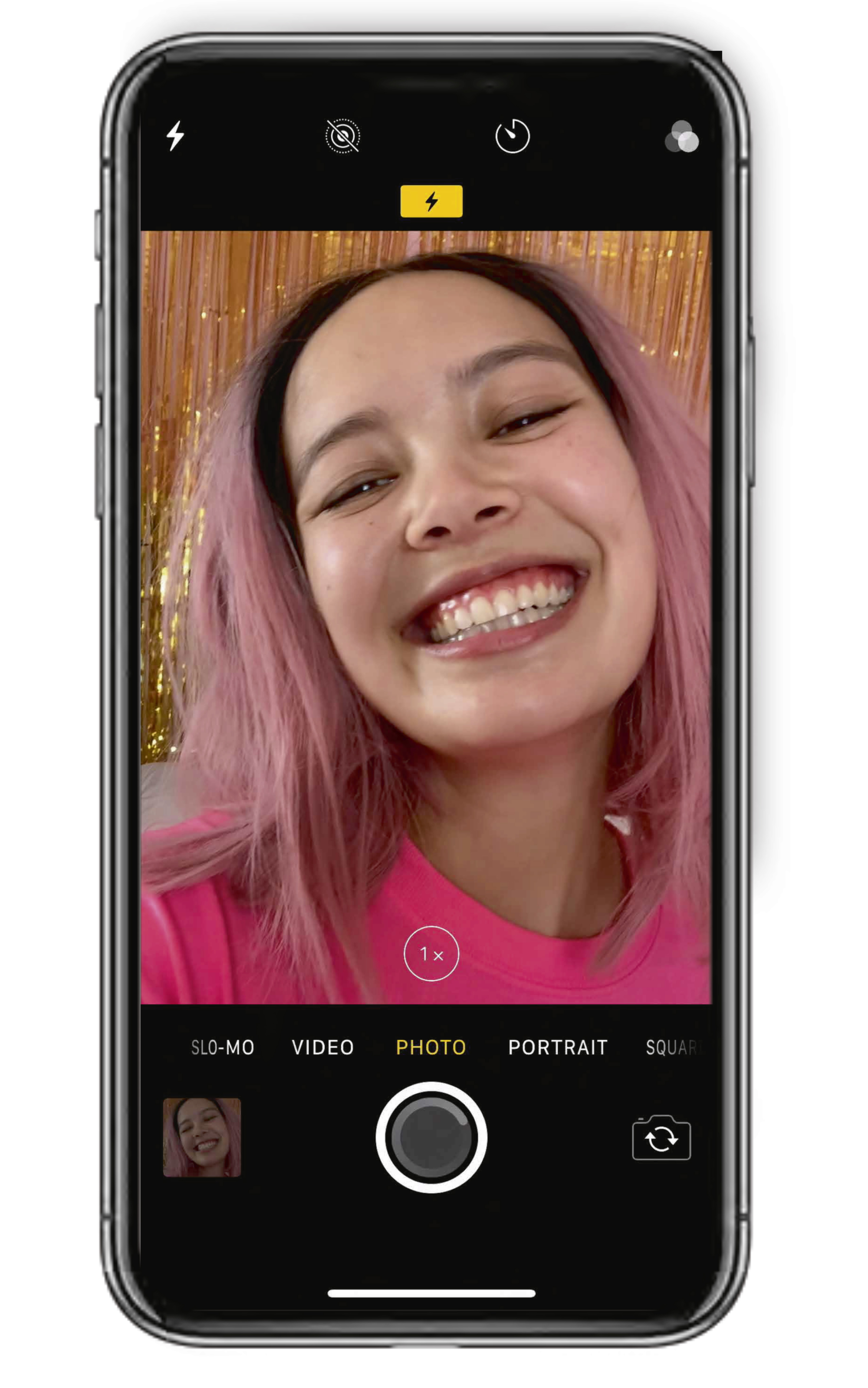

Content is a 2019 web series produced by Brisbane-based Ludo Studio and the ABC, with support from Screen Australia and Screen Queensland. The seven-episode title broke new ground by being created specifically for mobile devices, meaning that its presentation was optimised for vertical viewing – touted by the studio as a world-first for scripted comedy (and, indeed, previously seen only in rare contexts such as Australia’s Vertical Film Festival). The show mimics the presentation of apps like Instagram, Facebook and Messenger, and we also see smartphone pop-up graphics like those for messages, notifications and alarms.

The experience of watching and listening in this way is simultaneously familiar and unusual. So many of us consume media on mobile devices daily – short clips from television or film that have been shared via social media; amateur videos or pieces circulated by friends and family; or programs on Netflix or other streaming services – as part of our attempts to claim back some ‘me time’ while on public transport or waiting for takeaway. But, while Content is designed for mobile viewing and, thus, does not look alien, the experience of passivity certainly is. Each episode demands that, for somewhere between seven and seventeen minutes, we focus on that little screen while ignoring its other possibilities. Each pop-up forms part of the story and progresses the internal narrative of the show, but also prompts an almost impossible-to-deny impulse to ‘click through’ on our part. If nothing else, the show brings into sharp focus just how much we actually ‘do’ while we’re ‘doing nothing’ on our phones.

The show’s content is driven by the friendship between Lucy (Charlotte Nicdao) and Daisy (Gemma Bird Matheson). The young women are a classic odd couple in terms of their opposing personalities and clearly different trajectories, but their shared language online draws them together. There are moments when they should, and do, justifiably hate each other, yet the digital medium and its intricacies connects them in a way that only really makes sense as part of the immersive experience of watching and reading along with them. Content’s story includes not just ‘public’ actions like Instagram posts and stories, but also the ‘in-progress’ and ‘draft’ pieces that digital meaning-making relies on. The ellipses that appear on screen as a reply is being composed and the process of correcting or deleting a post before it is published are used as narrative devices to really impressive effect as well.

Content has drawn international attention for its innovation and ambition – not least because it is the ‘next big thing’ to come out of Ludo. (The first, and still biggest, is the children’s show Bluey, of course – and, for the record, Content could be no further from its predecessor in terms of approach, though there is a clear similarity in terms of sheer commitment, artistry and nuance.) In her round-up of the show for The New York Times, critic Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore compares Context to earlier tech-type ‘experiences’ such as 2014 low-budget horror film Unfriended (Leo Gabriadze) and 2018 psychological thriller Searching (Aneesh Chaganty). She also notes that the series’ staggered release ‘weekly at 6 p.m. Sydney time’ undoubtedly sought to ‘attract the attention of commuters looking for entertainment on their phones’.

Throughout its first season, Content proves that it is not just an exercise in technological novelty. Yes, in terms of characterisation and drama, the show treads familiar ground – so much so that, at times, Lucy and Daisy feel almost as over the top as other great female duos like Broad City’s Ilana (Ilana Glazer) and Abbi (Abbi Jacobson), or Australia’s own brilliant Kath (Jane Turner) and Kim (Gina Riley) from the eponymous TV series. Having said that, a thirty-second clip from the show’s first episode showing an apparently live-streamed car crash was so believable that, within two hours of being posted on Twitter, it was reportedly viewed more than 775,000 times. As Sebag-Montefiore offers, Content’s creators ‘wanted to ensure that the phone format would aid their storytelling rather than smother it’.

For all of its potential, there is an underlying sense of incompleteness in Content, too. Perhaps this is because everything happens so quickly and – understandably, given the form’s constraints – in such small pieces, which means ideas that would have been explored more deeply and explicitly in longer-form work become harder to grasp. The series is also limited by visual and sound factors, like a smaller frame and less technically advanced soundtrack. But it will be interesting to see how the showrunners develop the characters and narrative into the future. It might even make more sense to start over, with an upgrade or update of sorts. As ABC executive producer Que Minh Luu explained to The Guardian last year, in testing the Content before its release, the production team found that audiences ‘understood that this way of absorbing a story could be funny and dramatic and engaging to watch’.