Jill Bilcock on the Art of Film Editing

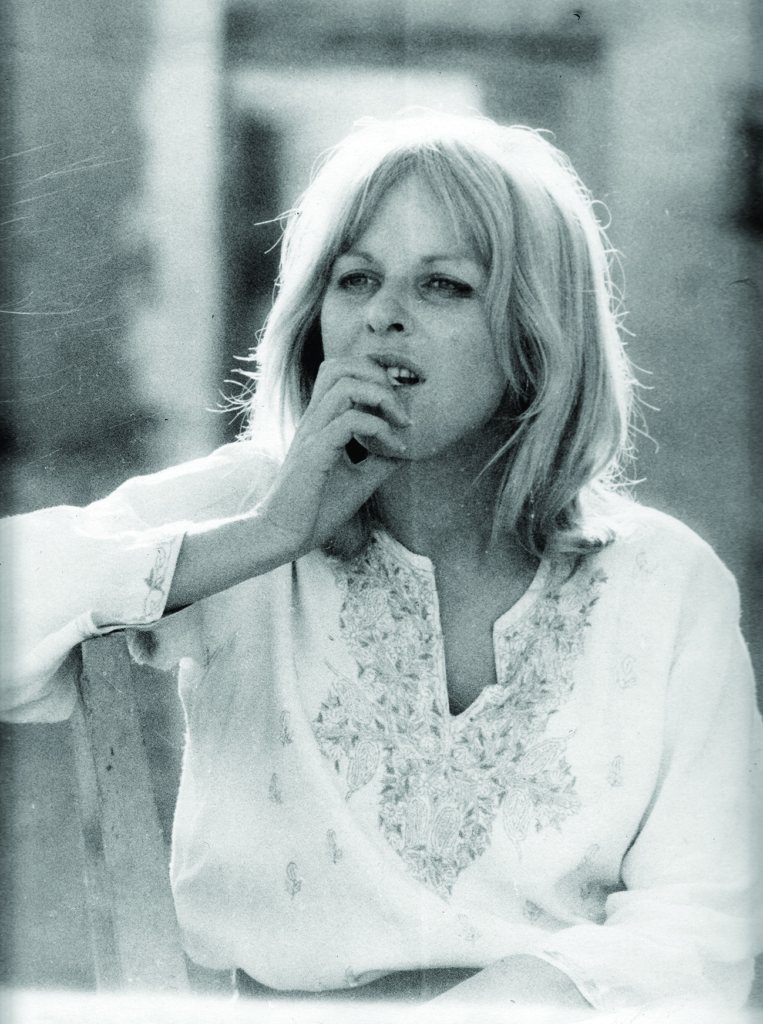

From Evil Angels (Fred Schepisi, 1988) and Muriel’s Wedding (PJ Hogan, 1994) to a trio of astonishing collaborations with Baz Luhrmann that culminated in a Best Film Editing Oscar nomination for Moulin Rouge! (2001), Jill Bilcock has significantly helped shape some of Australia’s most important films over the past thirty years.

Axel Grigor’s Jill Bilcock: Dancing the Invisible (2017) shines a light on the Australian editor’s instrumental career and – rarely for documentaries about filmmaking – on the pivotal process of editing. With the documentary released, I speak to Bilcock about the importance of making tough judgement calls, the power to shape characters and performances in the editing room, and how she has fought to retain the director’s vision.

Oliver Pfeiffer: You’ve said that editing is about trying to understand the director’s vision and then taking that vision to another level. How important is objectivity to this type of collaboration?

Jill Bilcock: You need to get to know your director. Everybody has a different idea of pace and vision as a director – you tend to find clues from the films that they like. I always ask for their favourite music, too, which will also give me clues about where that person’s head is [and] maybe how they might see the interpretation of what they’re trying to make. It’s just helpful to try and dig deep into where they’re coming from, and then collaborate in a way that, hopefully, brings that realisation beyond what they even imagined.

When you work with a male director, is there something from a female perspective – an alternative insight, perhaps – that you can offer, which a male editor might overlook?

Whether you’re male or female, some people tend towards having better observational skills of small details in people’s performances. Generally, I’ve noticed that females emotionally attach a bit more to those details. But […] everybody’s different; there is a bigger degree of patience [involved in] going through material. I find men do a great job of getting a structure ready more quickly, whereas [women] would tend to delve a little more into the emotional outcome. It’s certainly not a rule, though. Regardless, whether you’re a male or female editor, you have to be a good listener and interpret somebody else’s vision.

To a degree, you’re also ‘directing’ by guiding the audience’s perspective from an emotional standpoint. Would you say there’s a tendency to underplay the role of the film editor?

We probably are taken for granted a little bit […] A lot of documentary makers, for example, end up with a lot of footage and no script, so [editing for films like] that, I think, is taken for granted. People don’t put enough emphasis on editors who are making something without any structure at all – at least there is a script ‘wrap’ to a project when it’s a [fiction] film.

What’s the secret to your dynamic collaborations with Baz Luhrmann? You were there right at the beginning of his career!

Baz really enjoyed the fact that he felt he was a younger person with an older outlook and that I was an older person with a younger outlook. When we talked about things […] we bounced off each other. We always leapt forward with one another solving problems – so it was always very dynamic and very exciting to go to work, even though the problems were huge.

For the Strictly Ballroom (Luhrmann, 1992) dance finale, you edited the claps getting faster into the film, as the footage wasn’t originally shot that way. This demonstrates the power of the editor to shape a film and take it further.

It was in the script, but, because of the exciting way the film went, you really needed a big finale. We were limited by the way it was shot on that last day because we only had that environment, which was a real dance competition; we filmed on the Saturday and came in on the Sunday to pick up everything we thought we might’ve lost that we didn’t get. So we watched the rushes at 6am on Sunday morning in the lab, then rushed down to fill in all the blanks. I didn’t completely change the script – the script [said]: ‘and they did a great dance …’ However, the problem was [that] there wasn’t enough [of the] dance, so, to extend the clap, I used a different premise that was shot to create new steps, like [protagonist] Scott [played by Paul Mercurio] did in the film. Then we worked on the music to get it to where we wanted.

‘When you sit down to edit pictures and music, it’s a really great feeling. You feel you’re actually doing your own dance, and that you’re developing a rhythm and you’ve just got to keep it going.’

JILL BILCOCK

We often change music along with that, too. In Moulin Rouge!, ‘Smells like Teen Spirit’ was originally shot [with] a different beat, but then we decided to speed it up – so I had to make everything work at a different tempo, which was actually shot slower. Sometimes, when you start putting things together, you feel like you need more momentum or you need to slow something down a bit.

Editing parallel stories is something you’ve admitted is one of your strongest suits. The Moulin Rouge! tango sequence, which is crosscut with the parallel sequence of the Duke’s (Richard Roxburgh) assault of Satine (Nicole Kidman), is a great example. The chaos in the narrative is conveyed very strongly.

The tango was something that I cut a little bit every day for a very long time. I used to go, ‘Oh, Baz, this is driving me crazy!’ and he said, ‘You won’t regret this, Jill. It’s going to probably be the best thing you’ve ever done!’ He was kind of right because the problem was so huge and the footage was coming in relentlessly […] It was just overwhelming – but, when you sit down to edit pictures and music, it’s a really great feeling. You feel you’re actually doing your own dance, and that you’re developing a rhythm and you’ve just got to keep it going.

You’ve previously talked about your tendency to step out of the ‘safe zone’. Do you feel contemporary editors are still as bold as you have been, or is there a tendency to slip into conventional, ‘seamless’ editing?

It’s just that I did it when nobody else was doing it, probably. In America, I got some very bad press for Romeo + Juliet (Luhrmann, 1996), and a lot of editors were very angry about the way I’d cut that and [they] brushed it off as ‘MTV rubbish’ […] I was speeding up the maid [played by Miriam Margolyes] to cross the floor because the dialogue disperses, and you can’t have that bigger gap between the next line. So a lot of those crazy things I was doing there were initiated due to Shakespeare’s rhythm.

I’ve worked in England for the last year, and some of the editors are very good at doing all kinds of creative cutting. And in America, too – with Netflix – they’re being more creative, so I feel [contemporary editors] have really taken it on because of the way people use media now. I think they do a really good job most of the time. So now everyone goes, ‘Wow, isn’t that great – it’s cut conventionally!’ They seem to like a lot of slowdowns now.

How far do you believe editing can save a flawed production?

It’s definitely possible to rethink something and make a better result. You can often see things and realise, ‘Well, that’s just not funny because it’s way too slow and there’s too much explanation in the dialogue.’ I find most things are overwritten. They’re not overwritten on paper, but sometimes an actor has already given away something just in their face so you have to reassess the combination of the shoot and the written page to find out what it is you’re trying to achieve.

In Muriel’s Wedding, your editing turned Muriel (Toni Collette) into a more sympathetic character than she was originally!

Yes, she was pretty hideous in the first part. It’s not anybody’s fault; it’s just that, if you try and put [the film] together as per the script, it looks like too much tongue-poking and being hideous. Comedy can be too cruel sometimes, so you have to balance it so that the character ends up likeable. You need to love your characters whether they’re good or bad, and work on them to get them to the place that you want them to be.

It has been suggested that Sharon Stone’s performance during the infamous interrogation scene in Basic Instinct (Paul Verhoeven, 1992) was significantly re-formed in the editing room. Could you talk about that editorial power to shape a performance?

The director might have said, ‘Let’s go in that direction,’ or the editor did it; I don’t really know the true story behind this […] But you can do that easily with what you’ve got. You can actually change things to have a completely different meaning if you want to by the way you put it together. That’s the joy of solving lots of problems or just getting into material and redefining it. It’s quite easy to change something – but you always have to know the history behind these things.

It’s all about making a judgement call, too, isn’t it?

You have to have strong judgement, and the strength to chuck stuff out. Usually, what happens is that entire scenes – which you may think are brilliant – [have to] go. Sometimes you’ve just got to get rid of them as they’re doing something bad somewhere else in the story.

Have there been significant clashes with a director wherein you didn’t agree on a particular approach?

I’ve sometimes left the editing room and they’d go, ‘Oh, where’s Jill?’ and a day goes past and they realise that they better talk to me […] But everything has always been reconciled and moved on [from] brilliantly. I’ve been very selective in who I’ve chosen to work with. I love talent, I tend to pick my own projects and I’m very happy with the choices that I’ve made in my career.

Do you ever watch a film that you haven’t edited and think, ‘I would’ve lingered on that shot longer,’ or, ‘I would’ve cut that out completely’?

The biggest problem I have with watching films today is I can see where the studio stepped in – where the rhythm has changed in a strange way and characters aren’t rounded off properly because it’s getting too long. The people who put the money behind it are always very interested in the beginning and the end of the film; sometimes, they kind of butcher it about two-thirds of the way through, and it suddenly gets a bit weird. You realise the editor wouldn’t have done that, and that somebody’s been in there mangling things.

Have you ever experienced that yourself?

I was always sitting in the round table with soft management and fighting […] I’ve been on a lot of big-studio stuff that’s been a bit of a battle. I’ve fought that aspect of it: [that] it’s got to be what the director wants. However, I’ve seen it in other people’s work, so I can understand how it happens.

What do you enjoy most from your work as an editor?

Seeing [the finished product] with an audience. You find out so much. Things I thought were funny aren’t funny sometimes; things that they laugh at, they shouldn’t have. There’s a real joy from seeing something with an audience where it’s succeeding. You can’t ask for anything more than that. You’ve got to read it for what it is and learn from it. [Test screenings] can be helpful and also sometimes very depressing. What it does is verify your biggest fears, if there’s a problem, and then you’ve got a chance to fix it.