‘I never set out to make a zombie movie, it kind of just ended up happening,’ Little Monsters (2019) writer/director Abe Forsythe told film website Den of Geek last year, ‘but it happened in a really organic way, because it just fed into this stuff about my son, and his first year of kindergarten, and everything he’s taught me.’[1]Abe Forsythe, quoted in Matthew Schuchman, ‘Little Monsters: How Zombies Can Teach Us Kindness’, Den of Geek, 10 October 2019, <https://www.denofgeek.com/us/movies/horror-movies/283765/little-monsters-zombies-kindness>, accessed 21 October 2019.

Forsythe is best known for skewering Australian national myths. He wrote and directed the provocative race-riot satire Down Under (2016) and the buffoonish Ned Kelly spoof Ned (2003). By comparison, Little Monsters is not directly concerned with Australian identity – but it is shot through with Forsythe’s recognisably impertinent humour. As he explained to the website Screen Rant, the film was made independently, with a majority-Australian creative team, but closely followed the structure of an American studio comedy so that he and his crew ‘could subvert it with things you don’t ordinarily see in that type of movie. Then it would feel fresh and more shocking and more funny and more heartfelt, because [the audience] wouldn’t be expecting it.’[2]Abe Forsythe, quoted in Zak Wojnar, ‘Writer/director Abe Forsythe Interview: Little Monsters’, Screen Rant, 14 October 2019, <https://screenrant.com/little-monsters-movie-abe-forsythe-interview/>, accessed 21 October 2019.

Here, a zombie crisis stands in for a crisis of masculinity, wherein a callow protagonist who has dawdled too long on the threshold of adulthood must grow up at last. But, unlike other comedy-dramas with a ‘manchild’ at their centre, Little Monsters doesn’t reward Dave (Alexander England) for merely achieving baseline standards of maturity. Only by resolving the tension between his former self-indulgence and a newfound care for others does Dave find a meaningful humanity.

The Peter Pan syndrome

The manchild is currently one of Western cinema’s dominant archetypes. This character is in his late twenties – or even edging into his thirties or forties – yet he clings to a selfish lifestyle of hedonism and play. He shies from adult responsibilities: dressing and grooming; pursuing a career; cleaning and maintaining a home; managing his time; and offering care to others. Instead, he delegates this practical and emotional labour to parents, siblings, girlfriends and wives. He is only shocked from his complacency by an unexpected attachment to a woman, a child or both.

It’s telling that Big (Penny Marshall, 1988) uses a supernatural plot device to magically merge the two categories of ‘man’ and ‘child’, because there’s something uncanny about this state of arrested development. Peter Pan, JM Barrie’s 1904 stage play about a ‘boy who wouldn’t grow up’ – which was adapted into a popular 1953 Disney animated film (Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson & Hamilton Luske) – requires pixie dust and a fantastical ‘Neverland’ realm to sustain its protagonist’s liminal identity. Yet many films that depict manchildren in the ‘real world’ do so ambivalently, suggesting that these protagonists are trapped in self-created fantasies. Films such as Alfie (Lewis Gilbert, 1966), The Graduate (Mike Nichols, 1967), Arthur (Steve Gordon, 1981), Reality Bites (Ben Stiller, 1994), and even High Fidelity (Stephen Frears, 2000) and Something’s Gotta Give (Nancy Meyers, 2003) show how such men’s immature behaviour hurts others and may not provide them with lasting happiness. Part of what creates the boyish atmosphere of these films is the use of stylised, whimsical devices such as direct-to-camera addresses, fantasy sequences and dreamlike musical montages.

Other films buy into the fantasy, treating manchildren sympathetically. Studio comedies such as Billy Madison (Tamra Davis, 1995), Old School (Todd Phillips, 2003), Failure to Launch (Tom Dey, 2006) and Knocked Up (Judd Apatow, 2007) invite us to celebrate their antics, while indie films including The Big Lebowski (The Coen brothers, 1998), Greenberg (Noah Baumbach, 2010), Jeff, Who Lives At Home (Jay & Mark Duplass, 2011) and Adult Beginners (Ross Katz, 2014) ask us to care about the interior lives of shaggy blunderers.

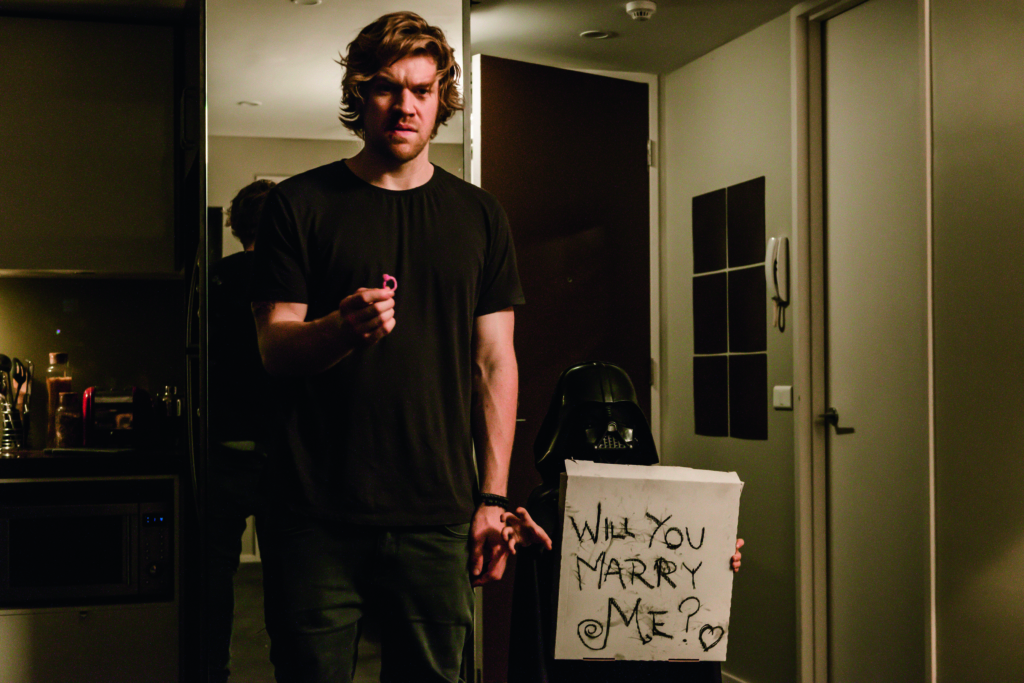

When we meet Dave in Little Monsters, he’s fighting endlessly with his girlfriend Sara (Nadia Townsend), who dumps him over his reluctance to have kids. For the first half of the film, Dave is unpleasantly petulant and pathetic, clinging to the faded cachet of his former metal band. He crawls home to Tess (Kat Stewart), the older sister who practically raised him, and reverts to an even more childlike state, sleeping in and playing violent videogames. Having a manchild on her hands is exasperating to Tess; she’s already a single mum to Felix (Diesel La Torraca), a sensitive, allergy-ridden five-year-old who keeps a ‘pet’ tractor, sincerely believes he has Darth Vader’s[3]The chief antagonist of the original Star Wars trilogy (1977–1983). powers … and, worst of all, idolises his foul-mouthed Uncle Dave.

When Dave begrudgingly takes Felix to school, he’s instantly smitten with kindergarten teacher Miss Audrey Caroline (Lupita Nyong’o), a chirpy vision in retro fit-and-flare outfits, who marshals her class using rhymes, games and songs. Hoping to get into Miss Caroline’s pants, Dave volunteers to chaperone a class excursion to Pleasant Valley Farm, a petting zoo and minigolf course whose gentle rural setting appeals to small children and international tourists.

A zombie crisis stands in for a crisis of masculinity, wherein a callow protagonist who has dawdled too long on the threshold of adulthood must grow up at last. But … Little Monsters doesn’t reward Dave for merely achieving baseline standards of maturity.

This locale also appeals, inexplicably, to the US military, which maintains a top-secret installation nearby. In a series of broadly sketched scenes, unspecified experiments at the base backfire and create zombies, which promptly escape and overrun Pleasant Valley. Will this force Dave to grow up at last?

An undead adolescence

‘It’s zombies again,’ drawls a laconic American lieutenant whose unit has been deployed to put down the Pleasant Valley crisis.

‘Fast ones or slow ones?’ asks a soldier.

The joke, of course, is that everyone here knows they’re in a zombie movie. This is why the military personnel are bland and interchangeable, their general (Marshall Napier) has an awful fake American accent and even the kindergarteners can tell that the zombies don’t look real in their shonky, low-budget make-up.

George A Romero’s zombie cycle – whose key films are Night of the Living Dead (1968), Dawn of the Dead (1978), Day of the Dead (1985) and Land of the Dead (2005) – formalised the genre’s now-familiar tropes, including that zombies crave human flesh, a zombie bite turns the victim into one and they can only be destroyed by major head trauma. But, more crucially, Romero transfigured the zombie’s original postcolonial context to mobilise twentieth-century American social anxieties. In its earliest folkloric form, as a revenant puppeteered by a Vodou sorcerer, the zombie represented the fear of enslaved Afro-Caribbean people that not even death could free them from the suffering caused by their loss of autonomy.[4]See Mike Mariani, ‘The Tragic, Forgotten History of Zombies’, The Atlantic, 28 October 2015, <https://www.theatlantic.

com/entertainment/archive/2015/10/how-america-erased-the-tragic-history-of-the-zombie/412264/>, accessed 21 October 2019. However, Romero’s zombies are scary because they blur the boundaries between the living ‘self’ and the corpse ‘Other’. They grotesquely mirror human appetites and impulses, becoming more sentient in each successive film; meanwhile, zombie outbreaks force humans to consider their own capacity for base violence. As Ken Foree’s Peter famously observes in Dawn of the Dead, ‘They’re us.’[5]The casting of Nyong’o, who was born in Mexico and is of Kenyan ancestry, doesn’t seem deliberately intended to evoke the postcolonial zombie; Miss Caroline’s race is never remarked on. However, it’s worth noting the intertextual ‘chime’ between Little Monsters and another 2019 film Nyong’o starred in, Us (Jordan Peele, 2019), which derives its horror from the same abject collapse of self and Other. As her character Adelaide’s family are confronted by their home-invading doppelgangers, the latter’s son, Jason (Evan Alex), echoes Dawn of the Dead when he whispers, ‘It’s us.’

This moment of existential horror embodies the ‘abject’: a realisation we seek to repress, or shrink from in revulsion. As psychoanalytic theorist Julia Kristeva argues in her influential book Powers of Horror, the abject is something that ‘disturbs identity, system, order’ because it embodies something liminal: ‘The in-between, the ambiguous, the composite.’[6]Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, trans. Leon S Roudiez, Columbia University Press, New York, 1982, p. 4.

We can consider the cinematic manchild an abject figure: he dwells in a kind of perpetual, ‘undead’ adolescence, shambling through adult life like a zombie. Accordingly, Little Monsters uses the zombie subgenre to emphasise that Dave is one of the ‘little monsters’. To emerge as an adult, he must ‘kill’ the manchild within. While Miss Caroline’s plucky hyper-competence recalls the no-nonsense black protagonists of Romero’s films,[7]Romero made a point of casting African-American actors in key roles, alongside mainly white zombies. Duane Jones plays the resourceful yet doomed hero of Night of the Living Dead; Foree appears in Dawn of the Dead; Terry Alexander stars in Day of the Dead; and, in Land of the Dead, Eugene Clark is ‘Big Daddy’, a sentient zombie who emerges as an antihero. Dave’s childish bumbling poses an existential threat – not only to himself, but also to actual children.

Tess has entrusted Dave with Felix’s EpiPen and showed him how to use it: ‘Blue in the sky, orange in the thigh.’ When the school group is trapped in the Pleasant Valley gift shop, Felix inevitably eats the wrong food and goes into anaphylactic shock. Dave, just as inevitably, gets the mnemonic wrong – ‘Orange in the sky, blue in the thigh’ – and injects himself, not Felix, with adrenaline. Miss Caroline realises there’s another EpiPen outside, in Felix’s backpack, and runs a gauntlet of zombies to retrieve it. Meanwhile, a shattered Dave – who had previously pooh-poohed Felix’s allergies – cradles his nephew, urging him not to panic.

Later that evening, Dave compliments Miss Caroline on her bravery, and she confesses that it hasn’t come easily. As a teenager, she obsessively followed her favourite band around the world; when they toured to Australia, she snuck into the singer’s hotel room, but was humiliated when her immature fantasy only delivered her to the police. Volunteering as a teacher’s aide led her not just to her current career, but to adulthood as well – because teaching is a constant, mindful practice of responsibility.

It’s a school day for Dave, too. He remembers how Tess once soothed him, and uses that knowledge to reassure the scared kids. And his renewed sense of purpose is his reward; he doesn’t ‘get the girl’. While he does become closer to Miss Caroline – and serenades her on ukulele to Neil Diamond’s ‘Sweet Caroline’ – it’s because he’s beginning to learn the same lessons she has.

Innocence and chaos

Zombies shamble over boundaries, transgressing attempts to contain them. They’re rather like kids that way. Anyone who’s ever been around a group of five-year-olds – or watched Kindergarten Cop (Ivan Reitman, 1990) – knows how chaotic they can be. They fizz with energy and curiosity, and almost completely lack self-control.

Little Monsters is at its most delightful when it shows the barely controlled anarchy of early-childhood play and the unselfconscious charisma of its child actors. (Felix’s classmate Max, played by Charlie Whitley, can hardly contain his mania to play putt-putt golf.) Miss Caroline wrangles her little monsters with endless pep and pedagogical tricks such as, ‘One, two, three, eyes on me!’ to which the kids obediently respond in chorus, ‘One, two, eyes on you!’

Little Monsters doesn’t treat its undead hordes as a source of genuine horror … Instead, this is a wholesome, earnest film whose energy comes from the interplay between childhood innocence and adult responsibility, and a consequent rejection of adolescent cynicism.

For Forsythe, zombies represent ‘the horrors of the world […] it’s easy to look at an instance of a child and the thing that’s going to corrupt and destroy them.’[8]Forsythe, quoted in Wojnar, op. cit. So Miss Caroline’s biggest challenge is to safeguard both the children’s physical wellbeing and their innocence, transforming a desperate attempt to flee the zombies into a fun impromptu tractor ride or conga dance. And after she’s held off a horde using only a shovel, she explains away her gore-splattered dress as the result of a strawberry-jam fight.

Personifying the corruption of childhood innocence, on the other hand, is Teddy McGiggle (Josh Gad), a superstar kids-TV entertainer who’s filming at Pleasant Valley when the zombies arrive. He’s all hectic charm when the cameras are rolling, but, under pressure, he’s a cowardly, alcoholic weasel. There’s something of Down Under’s electric profanity in this adult who is so openly contemptuous of kids. Best known for his whimsical voice work as Olaf in Frozen (Chris Buck & Jennifer Lee, 2013), Gad commits fearlessly to self-abjection as Teddy. Nothing is too disgusting: Teddy swigs hand sanitiser, poos his pants, sobs self-piteously to Dave that he’s ‘fucked so many moms’ and bites out the throat of a zombie child before bellowing, ‘How do you like it, huh?’ Somehow, the best gag at Teddy’s expense is that, before getting trapped in kids-TV hell, he was a serious actor who once studied with Al Pacino.

Despite its copious gore, Little Monsters doesn’t treat its undead hordes as a source of genuine horror; they operate mainly as sight gags, and even manage to moan along to ‘If You’re Happy and You Know It’. (My favourite zombie is the zookeeper whose face resembles a pincushion after he devours an unlucky echidna – though the koala-suited park-mascot zombie comes a close second.) Instead, this is a wholesome, earnest film whose energy comes from the interplay between childhood innocence and adult responsibility, and a consequent rejection of adolescent cynicism.

In Little Monsters, Forsythe implies that the things we fear – from cannibal cadavers to the prospect of parenthood – aren’t so scary after all if we can face them together. This is the joyful theme of the ukulele singalong that Dave joins in with Miss Caroline and her class. The song is Taylor Swift’s ‘Shake It Off’, an upbeat anthem about moving past negativity: ‘It’s like I got this music in my mind saying it’s gonna be alright’.

In a 1985 interview, Romero argued that his zombie films represented ‘the inevitable, inexorable force of change […] a society swallowing up itself, in this case literally’.[9]George A Romero, quoted in Jane Leavy, ‘Grave New World’, The Washington Post, 30 June 1985, <https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/style/1985/06/30/grave-new-world/1c2237a8-d365-4fa7-b0b5-6b47cc4d2911/>, accessed 21 October 2019. Eulogising Romero after his death in 2017, Variety critic Owen Gleiberman also suggested that the figure of the zombie represents ‘the hidden aggression we all feel deep down, as the price of too much civilization […] This is what it looks like when we forget who we are.’[10]Owen Gleiberman, ‘George A. Romero: A Maestro of Zombie Terror Who Created the Ultimate Horror-movie Metaphor’, Variety, 16 July 2017, <https://variety.com/2017/film/columns/george-a-romero-was-a-maestro-of-fear-1202497182/>, accessed 21 October 2019. Lost and angry, Dave had forgotten he was an adult. But, as he recognises in himself a capacity for care, he’s willing to shake off his moribund manchild self, along with his faded band T-shirt and electric guitar. For Dave, it’s the dawn of the dad.

Endnotes

| 1 | Abe Forsythe, quoted in Matthew Schuchman, ‘Little Monsters: How Zombies Can Teach Us Kindness’, Den of Geek, 10 October 2019, <https://www.denofgeek.com/us/movies/horror-movies/283765/little-monsters-zombies-kindness>, accessed 21 October 2019. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Abe Forsythe, quoted in Zak Wojnar, ‘Writer/director Abe Forsythe Interview: Little Monsters’, Screen Rant, 14 October 2019, <https://screenrant.com/little-monsters-movie-abe-forsythe-interview/>, accessed 21 October 2019. |

| 3 | The chief antagonist of the original Star Wars trilogy (1977–1983). |

| 4 | See Mike Mariani, ‘The Tragic, Forgotten History of Zombies’, The Atlantic, 28 October 2015, <https://www.theatlantic. com/entertainment/archive/2015/10/how-america-erased-the-tragic-history-of-the-zombie/412264/>, accessed 21 October 2019. |

| 5 | The casting of Nyong’o, who was born in Mexico and is of Kenyan ancestry, doesn’t seem deliberately intended to evoke the postcolonial zombie; Miss Caroline’s race is never remarked on. However, it’s worth noting the intertextual ‘chime’ between Little Monsters and another 2019 film Nyong’o starred in, Us (Jordan Peele, 2019), which derives its horror from the same abject collapse of self and Other. As her character Adelaide’s family are confronted by their home-invading doppelgangers, the latter’s son, Jason (Evan Alex), echoes Dawn of the Dead when he whispers, ‘It’s us.’ |

| 6 | Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, trans. Leon S Roudiez, Columbia University Press, New York, 1982, p. 4. |

| 7 | Romero made a point of casting African-American actors in key roles, alongside mainly white zombies. Duane Jones plays the resourceful yet doomed hero of Night of the Living Dead; Foree appears in Dawn of the Dead; Terry Alexander stars in Day of the Dead; and, in Land of the Dead, Eugene Clark is ‘Big Daddy’, a sentient zombie who emerges as an antihero. |

| 8 | Forsythe, quoted in Wojnar, op. cit. |

| 9 | George A Romero, quoted in Jane Leavy, ‘Grave New World’, The Washington Post, 30 June 1985, <https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/style/1985/06/30/grave-new-world/1c2237a8-d365-4fa7-b0b5-6b47cc4d2911/>, accessed 21 October 2019. |

| 10 | Owen Gleiberman, ‘George A. Romero: A Maestro of Zombie Terror Who Created the Ultimate Horror-movie Metaphor’, Variety, 16 July 2017, <https://variety.com/2017/film/columns/george-a-romero-was-a-maestro-of-fear-1202497182/>, accessed 21 October 2019. |