It was the thing that she got up in the morning for. And I’d say to her, ‘But what if you don’t recover from the surgery? What if you die?’ And she’d say, ‘But I’d die a woman.’ She loved the idea of seeing herself in the coffin in a fully female body.

So says Rowena Bianchino, director of Harbour Therapy Clinic in Coffs Harbour, of Colleen Young – the increasingly frail, elderly transgender subject of Ian W Thomson’s documentary Becoming Colleen (2019), from where these words were taken.

Oh, had Doris Wishman only not gotten there first with the title of her notorious 1977 transploitation quasi-documentary, or else the perfect subtitle for Thomson’s film would have been ‘Let Me Die a Woman’! Instead, the filmmaker opted for ‘Finding the Shoe That Fits’, shoehorning Young’s love of feminine footwear into an awkward, sugar-coated metaphor for a sadly abbreviated, late-in-life gender transition.

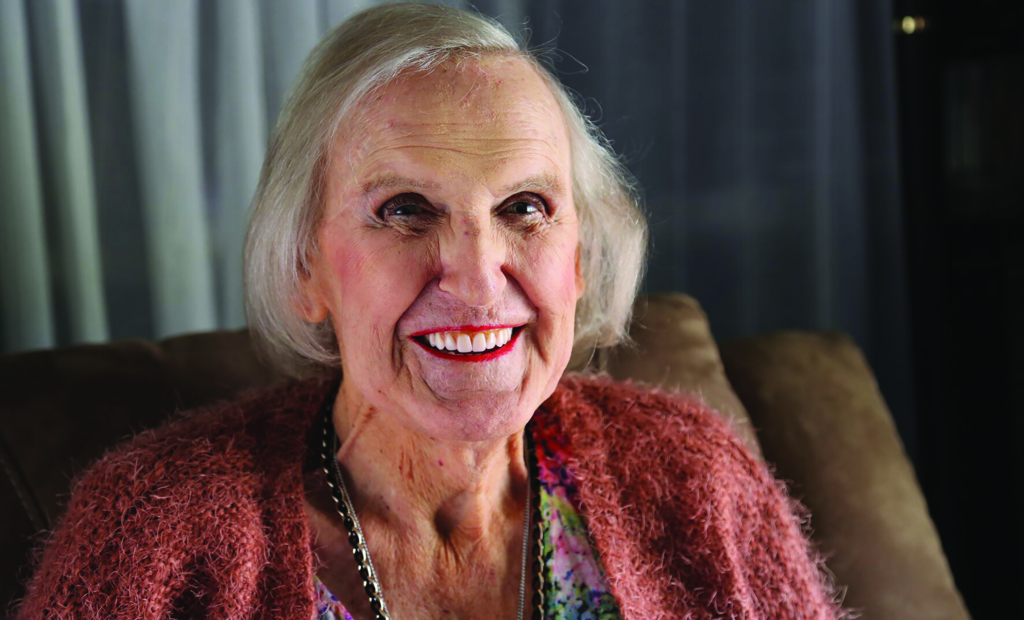

For a film whose focus is on someone determined, belatedly, to live authentically and be acknowledged as the woman she always wanted to be after eighty-two years performing a conventional male persona, it is apt that Becoming Colleen opens with a caveat that Young’s family and friends often refer to her ‘using the male pronouns they knew her by’. Misgendering – a perennial high-ranker among trans people’s greatest bugbears – is, alas, rampant in interviews throughout Thomson’s highly affecting, yet flawed (and occasionally even amateurish), documentary portrait–cum–gentle agitprop for greater LGBTQIA+ understanding.

By featuring this caveat at its very outset, the film frames proper pronoun usage as the foremost metonym for the acceptance of trans people’s gender-affirmation journeys. Thomson’s film is an amalgam of interviews with its subject and various family members, friends and helpers; nostalgic re-enactments of earlier days; recent footage of Young negotiating her limited personal space; cutaways to shoes; and still and moving images presumably from Young’s personal archive – all of which build a rich picture of a woman who, especially when still full of hope and relatively independent, is a sparkling delight to get to know. Indeed, it becomes upsetting when, in later scenes, we see Young with reduced mobility and depressed when countenancing the likelihood of never being approved for gender-affirmation surgery. Yet it is Becoming Colleen’s talking heads’ varying competence with pronouns that inevitably sticks in the mind, speaking most strongly to mainstream society’s struggle to respectfully recognise another’s true gender when its affirmation comes as a surprise.

Becoming linguistically competent

While Young’s sole surviving son, John, insists that he has been fine with her transition all along – when she tearily came out to him, he says, he simply replied, ‘I’ve known for years, Dad’ – he cannot bring himself in any of his to-camera addresses to refer to Young by any pronouns other than ‘he’, ‘him’ and ‘his’. Bianchino even recalls that John would ‘get offended’ whenever she corrected him about this during the early days of Young’s transition. ‘He’s still my father, regardless of what he wants to do with his life,’ is John’s most telltale utterance – smacking of simultaneous support and resistance. It’s little wonder, then, that Young’s granddaughter Siobhan blithely mimics her father’s misgendering in an awkward cameo towards the film’s close.

At the opposite end of the spectrum lie Bianchino, a near-paragon of trans allyship, and Emanuel Vlahakis, a medical specialist in sexual health who officiated over Young’s transition, both of whom affirm her gender linguistically whenever the camera is on them. Pippa Stanton, nurse unit manager at Coffs Haven Residential Care Service, is unstinting in her respectful pronoun usage, too. Her case is especially welcome, as this facility is run by Churches of Christ,[1]The facility’s proprietor is the organisation Fresh Hope Care, which identifies itself as a ‘Ministry’ of Churches of Christ in New South Wales; see ‘About’, Fresh Hope Care website, <https://www.freshhopecare.org.au/about/>, accessed 29 May 2019. the very sort of organisation that, by its name alone, sends tingles down the spines of ageing LGBTQIA+ folk everywhere.

Seesawing between the poles represented by Young’s family (unable and/or unwilling to tailor their vocabulary to linguistically embrace her transitional gender identity) on one hand and health professionals (who can be expected to abide by industry best practices) on the other is the very sweet Denise Ward. She’s Young’s neighbour and friend-cum-carer at Lime Tree Village, a retirement precinct for – as Bianchino describes it – ‘conservative, older Australians’; there, Young lived with her beloved wife, Heather, prior to the latter’s sad passing and to the panic attacks that precipitated Young’s hospitalisation.

Ward can be considered the avatar for the film’s, and its dramatis personae’s, grapples with Young’s gender identity – and with the slippery matter of gender more broadly. At one point, Ward states that, after Heather passed away, Young ‘was getting braver, out on the verandah with colours on, coloured shoes, and everyone in the village was just surmising that he’s wearing Heather’s shoes to feel closer to her.’ Here, it is ambiguous whether Ward alone is misgendering Young, or whether she is recounting how ‘everyone in the village’ had been referring to Young (or both). Later, reflecting on Young’s coming out, Ward again mixes masculine and feminine pronouns. But, near the end of the film, increasingly distressed at the certainty that her friend will never have the gender-affirmation surgery she has long hankered after, Ward has seemingly made a conscious effort to refer to Young wholly by her correct pronouns – and, on the one occasion when she slips, she immediately corrects herself.

Ward’s willingness to learn ultimately casts her in a very positive light; it’s a shame that same light couldn’t shine over Young’s family, too. Their inability, or reluctance, to address and refer to Young by the correct pronouns may well have been functions of having been brought up in a society of limited literacy concerning matters of gender identity; however, Ward nonetheless stands as proof that one can adjust one’s language over time, if one wishes to make a concerted and respectful effort to do so.

Elderly LGBTQIA+ people have long had reason to dread the prospect of spending their twilight years being attended upon by people who are insensitive, or even hostile, to fundamental matters of their identity and self-esteem.

Sins of omission

I first met Colleen Young two years ago. I was asked to film her as part of her coming out. She’d just come out at eighty-two as a transgender woman after living her life as a man, a married man, with sons, a whole career as a film projectionist and in the police force […] So I spoke to Colleen and asked her whether she would be interested in sharing her story.

It may just be an innocent matter of unfortunate phrasing, but the above words by Thomson[2]Ian W Thomson, in ‘Director, Ian W Thomson Talks About the Film’, Becoming Colleen official website, <https://www.becomingcolleen.com/videos/> , accessed 29 May 2019. reinforce an uneasiness I have about the level of agency Young was granted as the subject of Becoming Colleen. Thomson says he was ‘asked to film her’ – but by whom, exactly? In a documentary with several talking heads but no central narrator, how much influence was Young allowed in deciding what went in and what was left out? Authorship aside, Becoming Colleen, with its short, under-one-hour running time – perhaps a function of the need to be saleable to television, or a rush to complete production due to limited funding or film-festival premiere deadlines – frustrates by not giving a full-enough picture of Young’s backstory.

For one, it is odd that the film is presented as an entirely Australian story – a Coffs Harbour story, very particularly, complete with an early sighting of The Big Banana to reinforce the narrative’s specificity to that city and its conservative, National Party–heartland values. However, as Thomson himself admits during a radio interview, Young was a New Zealander by birth, only moving to Australia – and not to Coffs Harbour initially, but to the Gold Coast – when her and Heather’s sons were teenagers.[3]Ian W Thomson, in Sally Goldner, ‘Becoming Colleen, IWD, Parliament Breaching Laws and More’, Out of the Pan, 3CR, 10 March 2019, <https://www.3cr.org.au/outofthepan/episode-201903101200/becoming-colleen-iwd-parliament-breaching-laws-and-more>, accessed 11 May 2019. The elision of this detail from the resulting work is baffling; the film features Young speaking about many formative life events that could have occurred only in New Zealand, except not once does it offer viewers any visual or aural hints that position these experiences outside Coffs Harbour. At one point, Bianchino also mentions that, when Young came to seek her counsel, she spoke of bouts of anxiety and depression, and of a three-week internment at a mental-health facility, where she underwent electric-shock therapy. It is unfortunate, again, that such significant episodes as these aren’t positioned in time or space: did they happen in the backward and provincial New Zealand of, say, the 1950s, or even later, or elsewhere?

There are several other missed details throughout Becoming Colleen. Among Young’s many recollections to-camera, we learn that she had worked as a projectionist in a cinema near a shoe shop, which indicates an interest in film that a film about her could certainly have made more of. Becoming Colleen also excerpts some footage from home movies, and at the very least we could have been informed whether Young had shot these videos herself. And, of her time in the police force, an ominous, but unexamined, note is struck when Young says that ‘a lot of people were very vicious in those early days when [she] was a cop’. Were people unkind because they knew her secret, or intuited that she was closeted in one fashion or another? Did she fear being outed – or, worse, being bashed by ignorant, beery small-towners, notwithstanding her position of power to send any assailants to the lock-up? According to Thomson, the film ‘became much more than just a personal story about Colleen’s life’:

It became a story about transgenderism, aged care, [and] also about self-love and acceptance and what we need to do as a society to embrace the diversity that is inherent in our society and in our culture.[4]Thomson, in ‘Director, Ian W Thomson Talks About the Film’, op. cit.

To its credit, Becoming Colleen does – through Vlahakis – invoke the urgent issue of regional isolation, which is only magnified by old age and the pressure faced by LGBTQIA+ individuals to stay ‘in the closet’. As the film also makes plain, elderly LGBTQIA+ people have long had reason to dread the prospect of spending their twilight years being attended upon by people who are insensitive, or even hostile, to fundamental matters of their identity and self-esteem. Fellow patients in such facilities may not be healthy company to keep, either. Even a supportive friend among them – in Young’s case, an old dear by the name of Marjory Riordan – might still fail to, say, incorporate the appropriate pronouns when speaking anecdotally about their new, non-cisgender friend. Most significantly, Becoming Colleen does not draw specific attention to the struggles faced by elderly LGBTQIA+ folk to be addressed, dressed and respected in death as the people whom they had identified as during life. One might have thought that these could have provided the perfect coda to a filmic portrait of a woman with such a clear vision for how she wished to be treated both during the later stages of her life and in death.

Poignancy amid missteps

Heather died not long before filming commenced; Vlahakis posits at one point that her passing was the likely trigger for Young’s belated transition, with all the intimations of her own mortality that such a traumatic event would present. We never learn what pronouns Heather used to refer to Young, though we do know that she was the only person, during her own lifetime, in whom Young confided about her identity struggles. An ABC Life article reports that the latter only revealed her desire to live as a woman to Heather some twenty years into their marriage, upon being discovered by her dressed in her shoes and clothes.[5]Jennifer King, ‘Transgender Woman Colleen Young’s Dream of Being Who She Wanted Was Her Secret for More than 80 Years’, ABC Life, updated 15 May 2019, <https://www.abc.net.au/life/transgender-woman-colleen-youngs-dream-to-live-as-she-wanted/10928666>, accessed 29 May 2019. And, throughout the film, Young often attests to Heather’s kindness and supportiveness, and to the joy she derived in taking walks – and even cruises – as well as in attending parties with her wife with both of them dressed as women.

Thomson, wisely, gives Young the last, heartbreaking words spoken in the film, our subject advising us to ‘hope that some of those things come along that you would like. You probably won’t get them but one can but wish. The main thing in my life is wishing.’ After a slow fade to black, text appears on screen noting Young’s passing a few months after filming wrapped. More cheerily, it notes that Ward and Stanton were by her side, and that she did leave this world wearing her favourite pair of shoes. Whether this documentary – a testament to a life lived sadly unfulfilled in one critical aspect, and which will long outlive its subject – amounts to a wholly dignified farewell to this mortal coil is debatable. Indeed, at times, it is over-soundtracked and stilted with gormless, current-affairs-like camerawork, detracting from the film’s overall poignancy. But if, after proper use of pronouns, shoes can be said to serve as Becoming Colleen’s second-strongest metonym for gender affirmation, then let it be said that Young did indeed die a woman. Whether she was also interred thus – per the potent image that I opened this essay with, and which she herself wishfully projected – one can only hope.

https://www.becomingcolleen.com

Endnotes

| 1 | The facility’s proprietor is the organisation Fresh Hope Care, which identifies itself as a ‘Ministry’ of Churches of Christ in New South Wales; see ‘About’, Fresh Hope Care website, <https://www.freshhopecare.org.au/about/>, accessed 29 May 2019. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Ian W Thomson, in ‘Director, Ian W Thomson Talks About the Film’, Becoming Colleen official website, <https://www.becomingcolleen.com/videos/> , accessed 29 May 2019. |

| 3 | Ian W Thomson, in Sally Goldner, ‘Becoming Colleen, IWD, Parliament Breaching Laws and More’, Out of the Pan, 3CR, 10 March 2019, <https://www.3cr.org.au/outofthepan/episode-201903101200/becoming-colleen-iwd-parliament-breaching-laws-and-more>, accessed 11 May 2019. |

| 4 | Thomson, in ‘Director, Ian W Thomson Talks About the Film’, op. cit. |

| 5 | Jennifer King, ‘Transgender Woman Colleen Young’s Dream of Being Who She Wanted Was Her Secret for More than 80 Years’, ABC Life, updated 15 May 2019, <https://www.abc.net.au/life/transgender-woman-colleen-youngs-dream-to-live-as-she-wanted/10928666>, accessed 29 May 2019. |