Seeing and, perhaps more importantly, hearing Paul Damien Williams’ documentary Gurrumul (2017) in the wake of internationally renowned singer/songwriter Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu’s death in July last year was a strangely surreal experience. I recall sitting in the Forum Theatre towards the end of the Melbourne International Film Festival and listening to the distinct texture of his voice as it reverberated out into the expansive theatre. It was as if his voice was able to move into these spaces, these bodies, in the theatre and echo within them. The film was screened in three theatres across Melbourne that night, with introductions by members of Yunupingu’s family as well as speeches by Mark Grose (his manager) and Michael Hohnen (a long-time musical collaborator and close friend), both from Skinnyfish Music. These heartfelt talks spoke to each individual’s personal loss, but also resonated with the collective grief surrounding the sudden death of such a seminal figure and with his impressive legacy. Listening to his voice underscored the magnitude of what had been lost. In keeping with Aboriginal mourning customs, contemporary media practices usually recommend avoiding the reproduction of a deceased person’s image and name; it was therefore unclear whether Williams’ documentary would be screened at all. After consultation with Yunupingu’s family and community, who expressed a desire to have his work and memory preserved, however, the festival confirmed that the screening would indeed go ahead.[1]Tom Clift, ‘MIFF Will Proceed with Closing Night Screening of Dr G Yunupingu Documentary’, Concrete Playground, 11 August 2017, <https://concreteplayground.com/melbourne/arts-entertainment/miff-will-proceed-with-dr-g-yunupingu-documentary/>, accessed 17 May 2018.

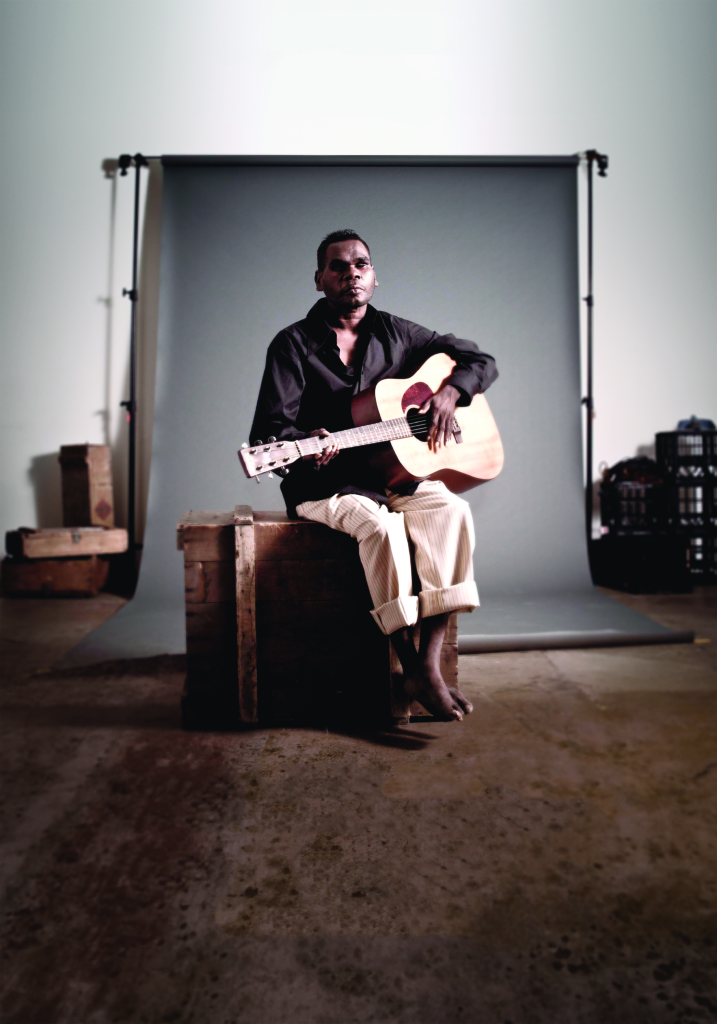

At the time of his death, Yunupingu was the most commercially successful Aboriginal musician in history to date.[2]Trevor Marshallsea, ‘Dr G Yunupingu: An Exquisite Singer Who “Spoke to the Soul”’, BBC News, 26 July 2017, <http://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-40725153>, accessed 17 May 2018. During his lifetime, his status as an internationally recognised singer/songwriter of course attracted immense media attention. Most notably, he was the subject of artist Guy Maestri’s 2009 Archibald Prize–winning portrait, and had been the focus of television specials, short documentaries and long-form articles. Equally well reported was Yunupingu’s intense shyness and reluctance to speak to media. So, while it is not surprising that Williams was eager to work with the famed musician, the task of presenting illuminating insights into this reclusive genius was still a very ambitious goal.

Prior to making the documentary, Williams had been living in Darwin, where he was employed by Skinnyfish as an in-house filmmaker. It was there that he was introduced to Yunupingu. At the time, Williams was also involved in smaller community projects in Galiwin’ku and other areas around Elcho Island, including two short films for NITV’s Songlines on Screen series: he was the consulting film-maker, co-writer and co-editor of Wardbukkarra: The First Song (Terrah Guymala, 2016), a Bininj story about the first song by the Nar-man-de mob; and producer and co-writer of Wurray (Keith Lapulung Dhamarrandji, 2015), about a nomadic warrior who journeys across north-east Arnhem Land. It was also during this time that Williams met Melbourne-based producer Shannon Swan – co-director, alongside Angelo Pricolo, of Lygon Street – Si parla Italiano (2013) – who pitched the idea of a documentary on Yunupingu to Hohnen and Grose.[3]Madman, Gurrumul press kit, 2018, pp. 4–5. It took about two years for the concept behind the film to be properly developed.

The strength of Gurrumul resides in how it evokes a very specific time and place; it is clear that Williams is invested in communicating the particularities of Yolngu culture, which, in turn, provide discrete anchors for the film’s exploration of Yunupingu’s life. This is achieved largely through sweeping aerial camerawork, detailed interviews with members of the community, and Williams’ documentation of the intimate interactions between Yunupingu and his family. The documentary also chronicles its subject’s career and creative collaborations, particularly with Hohnen, as well as the significance of the Elcho Island community to his work. There is a considerable amount of footage from Yunupingu’s international tours, which is interspersed with television appearances and radio interviews. But perhaps the most striking images are those from his youth, which illuminate his early life and his complex bonds with his community.

Speaking to me a few weeks before the documentary’s theatrical release, Williams explained some of the tensions that surface in the film between the demands of the international tour circuit and Yunupingu’s attachment to his family in north-east Arnhem Land: ‘You see two worlds […] with conflicting expectations and conflicting agendas. In a broader context, we expect Indigenous Australia to dance to the tune and the agenda that is set in white Australia.’ Indeed, the film allows for many of these interactions and miscommunications – which manifest in small and often subtle ways – to play out with very little editing or reframing. When Yunupingu is asked to perform a duet with Sting for the French TV show Taratata, it is revealed that he does not know who Sting is, and is unfamiliar with ‘Every Breath You Take’, which he is expected to translate. Furthermore, many of the song’s themes are foreign to Yolngu culture, and cannot easily be translated into Gumatj. The film documents these strained interactions with a particular kind of distance and doesn’t move to resolve or conflate these different worlds.

The strength of Gurrumul resides in how it evokes a very specific time and place … This is achieved largely through sweeping aerial camerawork, detailed interviews with members of the community, and Williams’ documentation of the intimate interactions between Yunupingu and his family.

This tension is felt in gestures towards understanding (demonstrated through efforts of translation and collaboration) that sometimes brush against cultural differences and fail to communicate the specificities of the songlines and stories that Yunupingu is telling. These miscommunications surface in footage from media interviews and rehearsals, and offer valuable insights into the processes of translation that are involved in these collaborations and conversations. The documentary occasionally uses the narration of Yunupingu’s aunt Susan Dhangal Gurruwiwi to clarify certain Yolngu traditions and the rituals and beliefs that Yunupingu grew up with. Her narration contexualises his upbringing and presents him as something of a liminal figure between these two worlds. In my conversation with Williams, he reflected on this liminality and framed the duality of Yunupingu’s role as one of competing expectations, asking, ‘Who wins? What’s more important?’ This provocation is never quite resolved, and questions of duality and liminality routinely manifest in different ways throughout the film.

The centrality of these disparities is emphasised in the film’s opening sequence, in which a title card offers definitions of ‘Yolngu’ and ‘balanda’ (slang for non-Indigenous Australians of European descent, or ‘whitefellas’). Indeed, the distinction between these words – and the different worlds they signify – is a tension that surfaces throughout Williams’ documentary, in conversations and in silences. The documentary highlights Yunupingu’s position as an internationally renowned artist and the tremendous amount of pressure put on him to perform a particular role for the media. This is apparent right from the film’s first scene, in which a journalist repeatedly rephrases her question to prompt a response from the musician, who remains resolutely silent. As Hohnen is shown explaining, English is Yunupingu’s ‘fourth or fifth language’. It is a painfully uncomfortable exchange and, while Hohnen ultimately steps in to speak for Yunupingu, the scene captures the latter’s reluctance to play the role expected of him by both the media and perhaps his audience more broadly as well. In this moment, Yunupingu’s well-documented shyness is palpable. It also evokes something of a miscommunication between balanda society and the language used to connect with and explore Yolngu songlines within his work.

Hohnen, in fact, routinely acts as a voice for Yunupingu, offering commentary in interviews and even talking to the crowd while the singer is on stage. As if to emphasise the pivotal role of Hohnen’s voice, the film opens with a black screen and the sound of him describing the surroundings to Yunupingu before an interview. While Yunupingu is the intended audience of his voice and the information it imparts, the audience in the cinema (seated in similar darkness) is made to be equally attentive. Yunupingu was born with complete vision impairment, and the formal approach here offers some understanding of his lived experience of blindness. It is a technique that Williams returns to several times throughout the film as a means by which to evoke the specifics of Yunupingu’s world and, in turn, to underscore the centrality of the voice, music and song in his life. In a related vein, Williams’ film includes interviews with Yunupingu’s family in which they reflect on their preconceived assumptions about how his disability would impact his access to opportunities in life and limit his agency and mobility in the world. These reflections brush against the narrative of Yunupingu’s rise to international fame as the nation’s most prominent Indigenous musician, and provide both context and texture to the film’s rendering of his early life.

Almost in counterpoint to his family’s concerns, Yunupingu rose to prominence with four critically acclaimed albums, an intensive domestic and international touring schedule, and a highly decorated career as a singer and songwriter. But, while these achievements allowed Yunupingu and his team to perform across the world, Williams’ documentary uncovers how scheduling pressures also negatively impacted the musician’s connection to his family and community. When Yunupingu fails to show up at Darwin Airport at the start of a scheduled tour of the US in 2010, Hohnen and Grose are put in the position of explaining and apologising to promoters and tour managers on his behalf. The promoters and tour managers express understanding – notwithstanding financial loss and poor business relations – due to the artist’s global reputation. Yunupingu, on the other hand, reiterates the importance of continuing to learn from his community, hearing their stories and songlines, and, perhaps more broadly, fulfilling his duty to pass these on and keep them alive. This is not directly explained by Yunupingu (who remains absent from the scene), but is instead communicated through Grose and Hohnen, who once again act as his mediators – highlighting the centrality of negotiation within Yunupingu’s team. It also hints at the textures and incongruities between these two worlds and, more importantly, offers the audience access to this conflict.

It is tempting to read Yunupingu’s reluctance to perform the role of ‘international star’ as a disavowal of celebrity culture … But his shy demeanour and seeming disinterest in fame might also be understood as arising from a sense of duty to protect and continue his culture’s traditions.

Here, again, Williams underscores the marked tension between balanda and Yolngu communities – especially in terms of the way in which each prioritises knowledge systems, which seems intrinsically bound to temporality. The scene at the airport presents Yunupingu’s absence as a disruption to a fixed schedule. The film cuts between scenes of Grose and Hohnen on the phone to various tour managers and promoters to create a sense of frantic energy. A shot of Grose asleep at his desk as the phone continually rings out is particularly effective at communicating the stress and time pressures of the situation. It is tempting to read Yunupingu’s reluctance to perform the role of ‘international star’ as a disavowal of celebrity culture; the documentary presents a man leaning away from the spotlight, refusing to self-promote and declining to divulge personal information. But his shy demeanour and seeming disinterest in fame might also be understood as arising from a sense of duty to protect and continue his culture’s traditions. It is not that Yunupingu is unaware of the time pressures of the touring schedule, but perhaps more that he feels these expectations are less important than the responsibility he has to his community. Also in this regard, of particular note is the film’s handling of Yunupingu’s relationship with Hohnen. The two men refer to one another as ‘brothers’, and the documentary masterfully captures the intimacy and depth of their relationship. Scenes of a relaxed and joking Yunupingu playing with Hohnen’s children in a hotel room lay bare a side of the musician that has remained obscured from the media. These scenes contextualise the world of this reclusive singer by showing who and what are most important to him.

In this way, time – and how it is spent – becomes a marker of what is deemed important and valuable. And, if music is a record of time, then for those outside his community, Yunupingu’s music might be heard as a call to listen, learn, echo and teach. Certainly, his work embodies a means by which to preserve Yolngu traditions. But, by combining Yolngu vocal and yidaki (didjeridu) elements with the minimalist stylisation of the Western classical tradition, it also resonates beyond this time, place and culture.

The real strength of Williams’ documentary lies in its revelations regarding how Yunupingu’s songs were brought into being. It is a fascinating study of the steps and negotiations involved in producing and promoting each album, securing international tours, and responding to a hectic press schedule. In one scene – a wonderful documentation of the creative process – an orchestra struggles to find the right Western notation through which to communicate the oral tradition of the Yolngu. When the music finally fits the sound after some trial-and-error, there is a sense that this commitment to authenticity has created an amazing resonance that does, in some way, do justice to Yolngu songlines.

In April this year, Yunupingu’s posthumous album Djarimirri (Child of the Rainbow) was announced as the first Indigenous-language album to reach number one in the Australian ARIA music charts.[4]Ben Smee, ‘Gurrumul’s Album Djarimirri Is First Indigenous-language Chart-topper’, The Guardian, 22 April 2018, <https://www.theguardian.com/music/2018/apr/22/gurrumuls-album-djarimirri-is-first-indigenous-language-chart-topper>, accessed 17 May 2018. In a song titled ‘Djolin’, Yunupingu sings, ‘Bäpaŋgurruna guywuyun’ (‘The sound of my fathers echoing through me from the past’[5]Michael Hohnen, ‘Gurrumul’s Djarimirri (Child of the Rainbow) – Behind the Songs of the Chart-topping Album’, The Guardian, 30 April 2018, <https://www.theguardian.com/music/2018/apr/30/gurrumuls-djarimirri-child-of-the-rainbow-behind-the-songs-of-the-chart-topping-album>, accessed 17 May 2018. ). Indeed, the notion of the internationally acclaimed singer being a conduit for the stories and knowledge of his elders and community is realised in the depth and resonance of his work, which echoes a tradition of oral storytelling. Reflecting on the significance of preserving these languages, stories and songs, Grose uses the analogy of tiles falling off the Sydney Opera House; he speculates on the public outrage that would transpire if a tile fell off every day. There are many ways in which the stories, voices, knowledge systems and languages of Indigenous communities are erased and forgotten. If Yunupingu’s story and the richness of his music are key elements in addressing this ongoing loss, then Williams’ documentary is a small but significant step in keeping the tiles firmly in place.

https://www.madmanfilms.com.au/gurrumul/

Endnotes

| 1 | Tom Clift, ‘MIFF Will Proceed with Closing Night Screening of Dr G Yunupingu Documentary’, Concrete Playground, 11 August 2017, <https://concreteplayground.com/melbourne/arts-entertainment/miff-will-proceed-with-dr-g-yunupingu-documentary/>, accessed 17 May 2018. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Trevor Marshallsea, ‘Dr G Yunupingu: An Exquisite Singer Who “Spoke to the Soul”’, BBC News, 26 July 2017, <http://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-40725153>, accessed 17 May 2018. |

| 3 | Madman, Gurrumul press kit, 2018, pp. 4–5. |

| 4 | Ben Smee, ‘Gurrumul’s Album Djarimirri Is First Indigenous-language Chart-topper’, The Guardian, 22 April 2018, <https://www.theguardian.com/music/2018/apr/22/gurrumuls-album-djarimirri-is-first-indigenous-language-chart-topper>, accessed 17 May 2018. |

| 5 | Michael Hohnen, ‘Gurrumul’s Djarimirri (Child of the Rainbow) – Behind the Songs of the Chart-topping Album’, The Guardian, 30 April 2018, <https://www.theguardian.com/music/2018/apr/30/gurrumuls-djarimirri-child-of-the-rainbow-behind-the-songs-of-the-chart-topping-album>, accessed 17 May 2018. |