In late 2016, Dr Nick Martin responded to a job advertisement for a senior medical officer. The details provided in the ad were scant: the location of the position was stated simply as ‘offshore’. When he rang to inquire about the position, he quickly deduced that the job was in immigration detention on Nauru.

‘I didn’t know much about it; I think the media blackout had been pretty effective,’ Martin says from his home in Sale, Victoria.

I knew of the existence of [the detention centres on] Nauru and Manus [Island], and I knew that Australia had been criticised on the international stage. I thought it would be interesting to go and see for myself what it was about.

The UK-born doctor had moved to Australia to work as a GP four years earlier, and had sixteen years in the Royal Navy under his belt. ‘[The detention centre] was run along very quasi-military lines, [which was] evident in the vocabulary they used – “mess hall”, “compounds”, “guards”,’ he says. ‘A lot of the security staff [were] ex-military [… there was] lots of routine, lots of paperwork, lots of bureaucracy, and so it felt quite familiar to me.’ He says he very quickly gained an appreciation of the scale of physical and mental health problems of the detainees on Nauru: ‘There was a huge burden of illness when I arrived there.’

Against Our Oath energetically prosecutes its main argument – that the way Australia’s offshore detention is run conflicts with the medical ethics of clinicians – as a piece of investigative journalism.

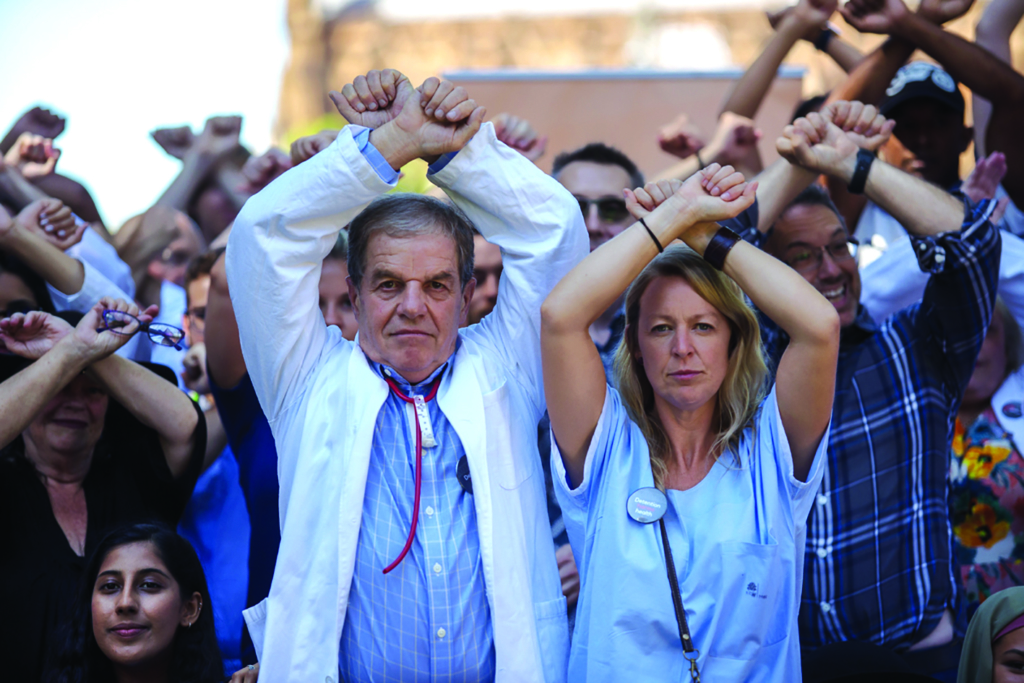

Martin is one of the clinicians featured in the new documentary film Against Our Oath (2019), the second major offering of independent filmmaker Heather Kirkpatrick. It is the latest addition to a growing catalogue of films that document the secretive operations of the Australian Government’s immigration-detention regime.

In her latest film, Kirkpatrick builds on the success of her 2013 documentary Mary Meets Mohammad, which follows the blossoming friendship between an Afghan Hazara asylum seeker held in Tasmania’s Pontville Detention Centre and an elderly member of the local knitting club. While that film was being made, the first groups of asylum seekers were being transferred to the newly reopened Nauru Regional Processing Centre,[1]‘Australia Reopens Asylum Detention in Nauru Tent City’, Reuters, 14 September 2012, <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-australia-asylum/australia-reopens-asylum-detention-in-nauru-tent-city-idUSBRE88D07120120914>, accessed 27 February 2020. marking the start of an extended period of offshore immigration detention that, for some, has not yet found an end.

As the years have dragged by for offshore detainees, more films have surfaced, shedding light on how Border Force operations and detention centres have been run. Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time is a 2017 collaboration between Kurdish-Iranian journalist and refugee Behrouz Boochani and Iranian-Dutch filmmaker Arash Kamali Sarvestani. The film, which was shot in secret on Boochani’s mobile phone, chronicles the lives of the asylum seekers and refugees in the Manus Island Detention Centre, as well as capturing the opinions of Manus Islanders about the existence of the compound on their island. Stop the Boats (Simon V Kurian), released the following year, makes the explosive claim that the Australian Border Force intercepted and bribed a crew of people smugglers bound for New Zealand to take seventy-one asylum seekers to Indonesia instead.[2]See Matilda Dixon-Smith, ‘Into the Void: Stop the Boats and Refugee Activism on Screen’, Metro, no. 202, 2019, pp. 86–9. In the 2018 documentary Border Politics (Judy Rymer), barrister Julian Burnside travels around the world to obtain the expert opinion of human-rights experts, academics, journalists and refugee advocates on the legality and international context of Australia’s offshore-detention policies.[3]See Anders Furze, ‘Lives Adrift: Julian Burnside and Judy Rymer on Border Politics’, Metro, no. 198, 2018, pp. 70–5 And Gabrielle Brady’s 2018 hybrid documentary Island of the Hungry Ghosts juxtaposes dreamy arthouse cinematography and an unsettling musical score with the clinical setting of social worker Poh Lin Lee’s counselling sessions with detainees on Christmas Island.[4]See Anthony Carew, ‘Heading for Deep Water: Interrogating Detention in Gabrielle Brady’s Island of the Hungry Ghosts’, Metro, no. 199, 2019, pp. 78–81.

Each of these films contributes a piece of the puzzle in their quest to tease out the nature of immigration-detention operations. In Against Our Oath, Kirkpatrick focuses on the tension between the demands of offshore-detention policies and the requirement for clinicians to adhere to their medical ethics: specifically, the edict of the Hippocratic oath that states that the welfare of the patient must always be paramount.

Against Our Oath was released at an important juncture in the political debate on the medical treatment of offshore detainees. The Medevac bill, passed against the wishes of the federal government in February 2019 to allow asylum seekers requiring urgent medical care to be transported to Australia, was repealed at the end of last year.[5]‘Medevac Repeal Bill Passes After Jacqui Lambie Makes “Secret Deal” with Coalition’, The Guardian, 4 December 2019, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/dec/04/medevac-repeal-bill-passes-after-jacqui-lambie-makes-secret-deal-with-coalition>, accessed 27 February 2019. At the time of writing, hundreds of asylum seekers are still languishing on Nauru and in Papua New Guinea. Some of the latter have now been incarcerated in Bomana Immigration Centre, where they are reportedly being pressured to return to their countries of origin.[6]‘Papua New Guinea: Detainees Denied Lawyers, Family Access’, Human Rights Watch website, 13 November 2019, <https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/11/13/papua-new-guinea-detainees-denied-lawyers-family-access>, accessed 26 December 2019.

Against Our Oath opens with the words of former refugee Munjed Al Muderis – recently named New South Wales Australian of the Year[7]‘2020 NSW Australian of the Year: Professor Munjed Al Muderis’, Australian of the Year Awards website, <https://www.australianoftheyear.org.au/honour-roll/?view=fullView&recipientID=2196>, accessed 27 February 2020. – explaining why he fled Iraq in the 1990s. As a junior surgeon, he was ordered to mutilate the ears of deserters, and witnessed the murder of the head doctor, who had refused to do so. Al Muderis managed to escape, and travelled to Australia, where he was granted refugee status. He is now one of Australia’s most sought-after orthopaedic surgeons. His account sets the scene for a discourse on how quickly human-rights considerations can be abandoned in the pursuit of nationalist agendas.

The revelations the director presents are – almost without exception – horrifying. Taken together, they form an irredeemably damning picture of how the system operates, on every level.

Unlike the grim, slow-moving grind of Chauka or the otherworldliness of Island of the Hungry Ghosts, Against Our Oath energetically prosecutes its main argument – that the way Australia’s offshore detention is run conflicts with the medical ethics of clinicians – as a piece of investigative journalism. While the director aims to steer clear of the pathos embraced by Island of the Hungry Ghosts, the pain and sorrow experienced by her subjects is plain to behold nonetheless. ‘I’m at the point where I’ve stopped apologising for all the shaky footage,’ Kirkpatrick said at the film’s Melbourne premiere, noting that Against Our Oath’s recordings of Nauru and Manus Island were captured covertly on smuggled phones.[8]Heather Kirkpatrick, Against Our Oath screening, 19 October 2019.

Syrian refugee Ali Kharsa, who arrived on a boat in 2013, relates his first hours in the Nauru Regional Processing Centre. ‘I saw some kids leaning on the gate … looking at me with their sad faces,’ he says. ‘My dad was really angry, because they took away our phones from us; they took everything from us. People in the compound were like, “Don’t do anything crazy, because they might hurt you.”’

Along with giving asylum seekers a platform, Kirkpatrick places clinicians front and centre in her narrative. In doing so, she offers us a glimpse into how the suffering inflicted by the offshore-detention system extends beyond the experiences of the asylum seekers themselves. Paediatrician Helen Young relates her involvement in the case of a baby sent to Australia for medical treatment. She received daily calls and emails from the immigration department, asking when the child and her mother would be ready for discharge. ‘People don’t recover from post-traumatic stress disorder when you send them back to the source of their stress,’ she says in the film. ‘We would never discharge a baby to somewhere that wasn’t safe.’ Young says she didn’t sleep for weeks while managing the infant’s case.

Martin says that most of the staff working on Nauru were negatively impacted by what they saw. ‘It would be impossible to spend any time on Nauru and to see what [the asylum seekers] had been through – and continue to go through, in many cases – and not feel a profound sense of anger at what the Australian Government is doing.’ He says a large number of former staff members from various organisations who worked on Nauru are still off on compensation for vicarious trauma experienced as part of their work.

Kirkpatrick throws the net wider than the medical community in her quest to understand the conditions in the detention camps, recording the testimony of former Manus Island Detention Centre security guard Steve Kilburn. In an interview that is difficult and distressing to watch, Kilburn struggles to find the words to describe the circumstances of detainee Reza Barati’s murder during a riot in the compound. In the interview, Kilburn’s lip starts to quiver as he asks why the Australian Government cannot save lives at sea while also treating asylum seekers with respect. ‘I think it’s simple. It shouldn’t be that hard,’ he says. ‘We should be able to do that.’ His observation of the effects of indefinite detention states an uncomfortable truth: ‘You saw when [the asylum seekers] arrived that they were strong, confident people who were, six months later, just … broken. We did that. We did that. Australia did that.’

Through her interviews, Kirkpatrick makes it clear that this state-sanctioned suffering has been going on for decades, through the onshore detention system. Simon Lockwood, the onsite doctor at the Woomera Immigration Reception and Processing Centre from 2000 to 2004, relates his experience in the film. ‘It took me ten years […] to recover psychologically from what I witnessed,’ he says. ‘The price I paid was nothing compared to the asylum seekers who came there.’

In a recent interview with German magazine Spex, Boochani also acknowledges the extent of the damage inflicted by Australia’s immigration policies. In particular, he references the detention of children as the zenith of the cruelty evident in the system. ‘Just imagine putting children inside cages. This is the deepest violence in the world,’ he says. ‘And I believe that the Australian government is not only torturing the refugees but also many people in Australian society. They are tired of witnessing this kind of violence.’[9]Behrouz Boochani, quoted in Holly Young, ‘“This Is the Deepest Form of Violence in the World”’, Spex, 10 April 2019, <https://spex.de/behrouz-boochani-interview-this-is-the-deepest-form-of-violence-in-the-world/>, accessed 26 December 2019.

Australia’s longstanding international reputation as a champion of human rights has taken a beating in recent years. The Australian Government has repeatedly ignored calls by the United Nations (UN) to overhaul its immigration-detention practices, such as from the UN’s Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, which in recent years ruled that Australia had breached numerous international human-rights laws.[10]Ben Doherty, ‘UN Body Condemns Australia for Illegal Detention of Asylum Seekers and Refugees’, The Guardian, 8 July 2018, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jul/08/un

-body-condemns-australia-for-illegal-detention-of-asylum-seekers-and-refugees>, accessed 26 December 2019. In Border Politics, Human Rights Watch executive director Kenneth Roth makes it clear how Australia is now perceived: ‘These days, when people think about Australia’s human-rights policy, they think foremost about Manus and Nauru,’ he tells Burnside. ‘Australia doesn’t want there to be a happy ending for the people in Manus and Nauru. They want them to be miserable as an abject lesson to other would-be boat people.’

But what of the residents of the Pacific island countries on which Australia has incarcerated asylum seekers? In an essay written for Griffith Review, academic Michelle Nayahamui Rooney picks up the thread of Boochani’s argument in Chauka – that Papua New Guineans also pay a price for hosting offshore-detention centres. Through poetry, she expresses the grief and anger she feels that her childhood home of Manus Island is now viewed by the international community as a ‘hell hole’, where the human rights of vulnerable people are cast aside. She also rails against the appropriation of the chauka bird – a symbol of the cultural identity of Manus Islanders – by detention-centre contractors to describe the notorious solitary-confinement cells in the compound. Rooney concludes her essay by pondering: ‘I wonder how the children on Manus today – indeed, all of our children – will view this period, and Chauka, in the future?’[11]Michelle Nayahamui Rooney, ‘Chauka, Where Are You?’, Griffith Review, no. 59, January 2018, available at <https://www.griffithreview.com/articles/chauka-where-are-you-notes-ethnographic-poem/>, accessed 27 February 2020.

Unlike Brady’s distressed counsellor and the latter’s young family in Island of the Hungry Ghosts, Against Our Oath lacks a strong protagonist to anchor the film, with Kirkpatrick instead following her nose and exploring tangential questions as they arise during her investigations, shining a light into every nook and cranny that she encounters. Her remit is comprehensive: we hear the accounts of detention contractor International Health and Medical Services staff, Australian Border Force bosses, politicians and legal advocates involved in the offshore-detention system. The revelations the director presents are – almost without exception – horrifying. Taken together, they form an irredeemably damning picture of how the system operates, on every level.

Kirkpatrick interweaves the horror of the first-person accounts of detention conditions with stories of hope and compassion: a refugee granted asylum in Canada; a successful community campaign in Brisbane to prevent a one-year-old burns victim from being returned to Nauru; and scenes in Vienna and Munich, where residents congregate to welcome asylum seekers into their cities. One German citizen pointedly tells the camera: ‘I hope that this gives an example to Australia […] because I read some stories that they are not so welcoming at the moment.’

A significant amount of Against Our Oath’s screen time is devoted to tracing the history of medical ethics, starting in Kos, Greece, the birthplace of Hippocrates. We travel further through Europe to learn about the Declaration of Geneva, formulated in the aftermath of World War II and the Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial. Kirkpatrick discovers that doctors formed the largest proportion of Nazi party members of any occupation, and that the eugenics policies enacted by clinicians during the war resulted in 400,000 people being murdered. In light of the shocking scale of human exterminations undertaken during this period, resolutions developed after the Doctors’ Trial formed the basis of modern medical ethics. The unspoken question raised by this history lesson looms like a spectre: is our society sliding backwards morally?

As the Melbourne screening of Against Our Oath drew to a close, audible sobs escaped the throats of audience members as, one by one, the images of asylum seekers who lost their lives in offshore detention appeared on the screen in silence. There were many clinicians and refugee advocates in the audience; some had known the deceased men personally.

Back in Sale, Martin says he hopes that Australian doctors and nurses will go and see the film. He laments how politicised what he sees as a medical issue has become. ‘Some people will feel that treating refugees with decency and respect is the same as opening our borders […] I think they are fundamentally wrong on that,’ he says. ‘The whole debate has become toxic. I think the duty of care towards asylum seekers should transcend politics.’

https://www.againstouroath.com

Endnotes

| 1 | ‘Australia Reopens Asylum Detention in Nauru Tent City’, Reuters, 14 September 2012, <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-australia-asylum/australia-reopens-asylum-detention-in-nauru-tent-city-idUSBRE88D07120120914>, accessed 27 February 2020. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Matilda Dixon-Smith, ‘Into the Void: Stop the Boats and Refugee Activism on Screen’, Metro, no. 202, 2019, pp. 86–9. |

| 3 | See Anders Furze, ‘Lives Adrift: Julian Burnside and Judy Rymer on Border Politics’, Metro, no. 198, 2018, pp. 70–5 |

| 4 | See Anthony Carew, ‘Heading for Deep Water: Interrogating Detention in Gabrielle Brady’s Island of the Hungry Ghosts’, Metro, no. 199, 2019, pp. 78–81. |

| 5 | ‘Medevac Repeal Bill Passes After Jacqui Lambie Makes “Secret Deal” with Coalition’, The Guardian, 4 December 2019, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/dec/04/medevac-repeal-bill-passes-after-jacqui-lambie-makes-secret-deal-with-coalition>, accessed 27 February 2019. |

| 6 | ‘Papua New Guinea: Detainees Denied Lawyers, Family Access’, Human Rights Watch website, 13 November 2019, <https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/11/13/papua-new-guinea-detainees-denied-lawyers-family-access>, accessed 26 December 2019. |

| 7 | ‘2020 NSW Australian of the Year: Professor Munjed Al Muderis’, Australian of the Year Awards website, <https://www.australianoftheyear.org.au/honour-roll/?view=fullView&recipientID=2196>, accessed 27 February 2020. |

| 8 | Heather Kirkpatrick, Against Our Oath screening, 19 October 2019. |

| 9 | Behrouz Boochani, quoted in Holly Young, ‘“This Is the Deepest Form of Violence in the World”’, Spex, 10 April 2019, <https://spex.de/behrouz-boochani-interview-this-is-the-deepest-form-of-violence-in-the-world/>, accessed 26 December 2019. |

| 10 | Ben Doherty, ‘UN Body Condemns Australia for Illegal Detention of Asylum Seekers and Refugees’, The Guardian, 8 July 2018, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jul/08/un -body-condemns-australia-for-illegal-detention-of-asylum-seekers-and-refugees>, accessed 26 December 2019. |

| 11 | Michelle Nayahamui Rooney, ‘Chauka, Where Are You?’, Griffith Review, no. 59, January 2018, available at <https://www.griffithreview.com/articles/chauka-where-are-you-notes-ethnographic-poem/>, accessed 27 February 2020. |