‘In the world’s biggest city, stories unfold in public spaces,’ says Olivia Martin-McGuire, in her feature-length documentary China Love (2018). As an Australian photographer living in Shanghai, Martin-McGuire often saw brides posing with their beaus in front of the city skyline – in plumes of chiffon, with blushing make-up, blow-wave curls, fake lashes and fuchsia bouquets – accompanied by professional photographers freighted with expensive gear. A performance of wedded bliss. But the brides weren’t yet brides: every year, thousands of young Chinese couples take pre-wedding photos up to six months before the official proceedings. Whose fantasy do the photos project, and why is it so important?

Such is the power of photography in selling and building new cultural myths of marriage. China Love begins with these chintzy pre-wedding images – which, locally, form an entire genre of commercial photography – to chart the rise of the marriage-industrial complex in modern China, a society in a state of rapid and often-contradictory change as free-market values mingle with authoritarian traditions. If the new Chinese dream is an emulation of everything American, what role do pre-wedding photos play in that dream?

Co-funded by Screen Australia and the ABC, and produced by Media Stockade’s Rebecca Barry and Madeleine Hetherton, China Love has the hallmarks of the kinds of bigger budget docos that Australian audiences are used to seeing. The filmmakers lead us through China’s shifting cultural narrative of marriage – from the era of the Cultural Revolution to the present – and inside the commercial machinations of the companies benefiting from the pre-wedding-photo boom. It is forty years since China opened up its economy to the free market. Although the middle class has flowered, along with the number of billionaires, millions of Chinese people remain in poverty.[1]Around 30 million people, relative to the poverty line set by the Chinese government; see Ralph Jennings, ‘Despite China’s Fast-growing Wealth, Millions Still Remain Poor’, Forbes, 4 February 2018, <https://www.forbes.com/sites/ralphjennings/2018/02/04/why-tens-of-millions-remain-poor-in-china-despite-fast-growing-wealth/>, accessed 3 August 2018. Weddings, we learn, have become loci of aspiration and wealth wish fulfilment.

Although the middle class has flowered, along with the number of billionaires, millions of Chinese people remain in poverty. Weddings, we learn, have become loci of aspiration and wealth wish fulfilment.

Historically, weddings in China were arranged by family members, matchmakers or the state, and, during the Cultural Revolution, photos often served as proof of the marriage. Today, photos fuel an A$80 billion industry[2]Media Stockade, China Love press kit, 2018, p. 2; see also Lisa Murray, ‘At the Perfect Chinese Wedding, Photographs Rule’, Australian Financial Review, 17 September 2015, <https://www.afr.com/lifestyle/at-the-perfect-chinese-wedding-photographs-rule-20150914-gjlwqt>, accessed 3 August 2018. that sells dreams of riches and equates them with happiness. In the documentary, elderly couples who survived the Cultural Revolution tell the stories of their black-and-white wedding photos, in which they appear in Mao-style clothing, seated side by side and unsmiling. That era wasn’t just absent of wedding dresses and gifts, but of a concept of romantic love itself. ‘Did you think of the idea of romance at the time?’

Martin-McGuire asks an elderly couple who married in the 1960s. ‘Romance – what?’ the woman replies. It was a time when lovers were more likely to inform on each other than hold hands or declare adoration. Later, another elderly couple describe the Chinese view of marriage as being like a thermos bottle: cold on the outside, hot within. Together, they water rows of pot plants lined up on their tiny kitchen bench in a makeshift indoor garden, the smog-filled city skyline in the background.

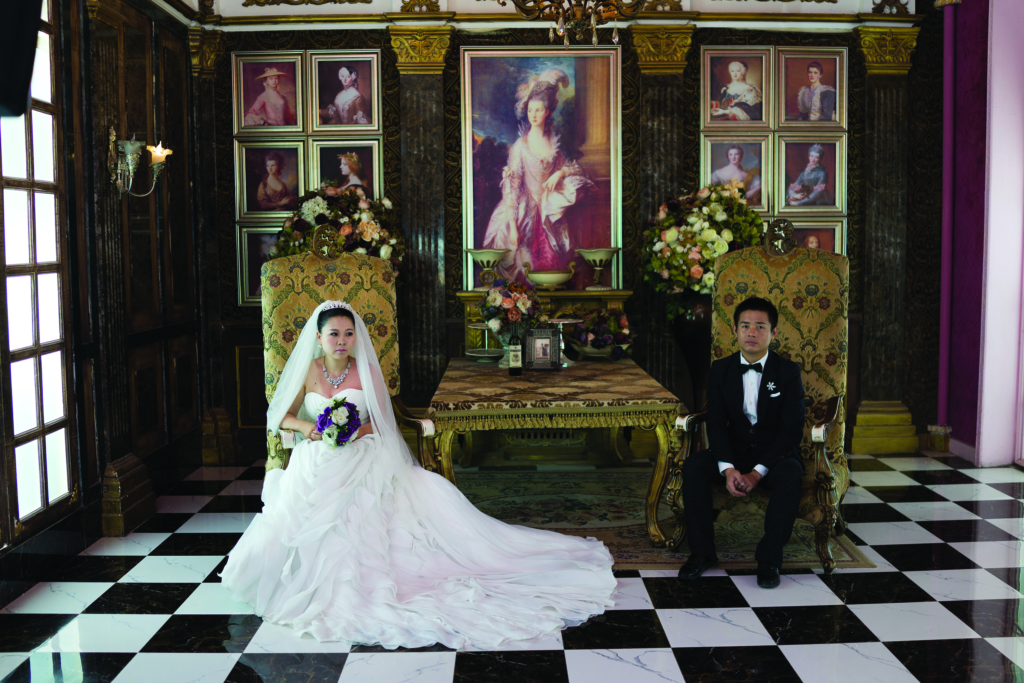

It is through comparisons between present-day weddings and those in the 1960s and 1970s that Martin-McGuire traces the arc of China’s cultural narratives about marriage. Over the past fifty years, it has transformed from an institution of obligation to one of upward mobility and social perfectionism. Nowadays, price points for pre-wedding photo packages range from A$300 to A$400,000.[3]Lisa Murray, ‘China Love Documentary Captures the Country’s Wedding Excesses (at $80b a Year)’, Australian Financial Review, 8 June 2018, <https://www.afr.com/lifestyle/arts-and-entertainment/film-and-tv/china-love-doco-captures-the-countrys-wedding-excesses-20180606-h111ca>, accessed 3 August 2018. Just as there are destination weddings, there are destination photoshoots – or, rather, studio replicas of exotic destinations. Sets are themed: fairytale wonderland, underwater Eden, Renaissance museum and uber-rich mansion. Pre-brides can be a princess in a forest, inhabit a throne room or choose the ‘small European castle’ look. They can be all of these things, switch costumes and sets, and select the final airbrushed images.

The extravagance and scale of these packages are brazen. One young bride, Viona, who is Chinese-Australian, says that she wants her pre-wedding photos to ‘depict an upper-class lifestyle’. She speaks of her desire ‘to present [her] beauty, and [her] mother’s beauty, and [her] grandmother’s beauty’, and of her ‘dream of a rich, beautiful life […] The dream is to be wealthy and happy and not to have to do anything!’ Her mum watches on, nodding enthusiastically at the camera.

We then meet the man taking Viona’s money. Allen Shi is the chairman of The Jiahao Group, which has invested in over thirty luxury brands in its efforts to advance what it calls the ‘independent cultural industry ecosystem’.[4]See The Jiahao Group official website, <http://www.thejiahaogroup.com>, accessed 31 July 2018. As the film reveals, Jiahao’s pre-wedding division – but a sliver of its enterprises – comprises 7000 employees and 300 studios trading in images of joy and prosperity and promising to treat its clientele as celebrities and princesses. Shi is a rags-to-riches tycoon who aspires to conquer the Asian market, as well as those in Europe and the US, with an aggressive, expansionist business plan. The reception desks of his company bear the slogan ‘Globalizing the Happiness Industry!’

As a marriage magnate (yes, there is such a thing), Shi enforces military routines on his staff, issuing on-the-spot fines for those who fail to match their photographs to the quality of the templates. His empire requires internal make-up departments, stylist teams and outfit partnerships, and he uses shame as a managerial style, threatening to fire underperforming staff at meetings in front of their peers. Wearing flamboyant bow ties and patterned blazers, Shi is flanked by three anxious personal assistants, whose flagrant Stockholm syndrome could sow the seeds of a whole new documentary.

Pre-wedding photos … embody a strange mix of financial pressure, social cohesion and new, Westernised aspiration. Perhaps Chinese youth, like those in Australia, want it all – romantic love, domestic partnership, financial stability.

Shi is new money. His pride in foreigners’ interest in his achievements is so naked that he takes to capturing selfies with the documentary crew. His number-one personal assistant, an American, intones his boss’s mantras, such as ‘Face is the most important thing’, straight to the camera. Indeed, promoting this presentation of face – brand, image, status – has become Shi’s very business model. ‘I came from poverty,’ Shi tells the crew on the way to the airport to meet with potential American investors. ‘I felt weak and powerless, like a blade of grass about to be flattened.’

This is why Shi has become the man who has commodified marriage in China. This is why he sells happiness, why he has 200 customers a day and why he takes US$3.1 million worth of pre-wedding photography bookings a year. This is how an entrepreneur learns to associate net worth with contentment, and life success with business acumen. Perhaps the Chinese and American dreams are not so far apart after all.

But marriage is not all aspiration. The Chinese government has a term for an unwedded woman over the age of twenty-eight: a ‘leftover’. Those approaching leftover status are represented at marriage markets, where women are promoted via their age, career, height and income. It’s their last hope, and a far more ruthless arena for instantaneous judgement than Tinder. ‘Youth and beauty are going to leave you behind,’ says Viona, ever the pragmatist despite her deep investment in the marriage myth, as she wanders the marriage market at the People’s Park in downtown Shanghai. Here, pre-wedding photos, and the broader marriage industry helmed by The Jiahao Group, embody a strange mix of financial pressure, social cohesion and new, Westernised aspiration. Perhaps Chinese youth, like those in Australia, want it all – romantic love, domestic partnership, financial stability – though are more plain-spoken about the practical dimensions of their arrangements.

It becomes clear that Chinese parents both feel and furnish the pressure: mothers fear the shame of unmarried children, while fathers lament providing a down payment for their engaged children’s first homes. It’s emotional, too: we meet a man who cannot sleep as his daughter’s wedding approaches; he can’t bear to let her go to another household.

Because of the burdensome costs of marrying, pre-wedding photos emerge as more fantastical, and more fraudulent, than the weddings themselves. When we finally see a matchmaker-introduced couple, Li and Jun Bo, marry, it’s a sweet and modest affair that begins in the humble apartment of Li’s family. In an effort to prove his worth to them, Jun Bo washes Li’s feet and kisses them before carrying her to the car so that she does not touch the ground.

And for those who married during the Cultural Revolution, pre-wedding photos take on an entirely different meaning. In a series of on-screen vignettes, a charity offers free events and photos, in office-like community halls, to elderly couples whose awkward, army-like wedding photos served the same practical purpose as passport shots. Dolled up in cheap jewels, pearlescent lipstick and shiny formal wear, there is something sweetly infantilised about these couples, in the same way a small child dons a tailored suit for a funeral. ‘What our generation experienced is beyond belief,’ says one woman who has been married for sixty-nine years. Any notion of aspiration, of affluence, of climbing the social ladder and projecting an image of success, falls away.

‘Thank you for being willing to build a better life together,’ says a man to his partner. ‘Thank you for having treated me well,’ she replies.

All documentaries take the messy material of life and politics and shape it into a story. The blind spot of China Love’s story is that it does not follow anyone who deviates from the fantasy of pre-weddings and from marriage itself – or who has a less transactional view of the marriage compact. Certainly, we see no visions of unmarried love, nor do we hear about whether it exists. If there are any aberrations from The Jiahao Group’s marriage-industrial complex in contemporary China, other ways of doing contemporary marriage, they are not shown – an obvious conceptual question the documentary makers have left unaddressed.

Rather, we return to Viona, now jobless and living in Darwin. Still childless a year after her wedding, she weeps, but she chooses what she calls ‘opportunities’ over ‘freedom’ as she returns to China to trade a less pressured life for better job options. After the wedding, Martin-McGuire seems to be saying, the fantasy projected in the pre-wedding photos rarely continues. Yet the documentary ultimately shies away from delving deeper into the fissures and disappointments of modern China’s wedding-fantasy sector.

The final question that the documentary turns away from relates to what, exactly, marriage means in 2018. Even in the West, marriage has a mercantile past. As such, there is something of a false dichotomy at the heart of China Love: the assumption of love marriages as an eternal ideal, from which China’s wedding industry diverges as an abnormality. Yet romantic love, and all the expectations that go with it, is as much a cultural construction as the Cultural Revolution’s utilitarian, duty-bound vision of marriage and Jiahao’s fabrication of picture-perfect bliss. Martin-McGuire’s documentary therefore offers, first, a Westerner’s portrait of change in modern China and, second, an examination of new Chinese approaches to marriage.

Marriage is a concept that means a lot to many but holds disparate definitions. Here, I’m talking about marriage in all its iterations – an institution, an agreement, a business deal, a compromise, a domestic arrangement, a convenience, a promise to be breached, a spiritual meeting, a system of property and inheritance. Now, as we see in China Love, it is also an attempt at personal brand management and a social and financial necessity in an increasingly class-divided society. Perhaps, we might decide one day, it should also become a vestige of the past.

Endnotes

| 1 | Around 30 million people, relative to the poverty line set by the Chinese government; see Ralph Jennings, ‘Despite China’s Fast-growing Wealth, Millions Still Remain Poor’, Forbes, 4 February 2018, <https://www.forbes.com/sites/ralphjennings/2018/02/04/why-tens-of-millions-remain-poor-in-china-despite-fast-growing-wealth/>, accessed 3 August 2018. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Media Stockade, China Love press kit, 2018, p. 2; see also Lisa Murray, ‘At the Perfect Chinese Wedding, Photographs Rule’, Australian Financial Review, 17 September 2015, <https://www.afr.com/lifestyle/at-the-perfect-chinese-wedding-photographs-rule-20150914-gjlwqt>, accessed 3 August 2018. |

| 3 | Lisa Murray, ‘China Love Documentary Captures the Country’s Wedding Excesses (at $80b a Year)’, Australian Financial Review, 8 June 2018, <https://www.afr.com/lifestyle/arts-and-entertainment/film-and-tv/china-love-doco-captures-the-countrys-wedding-excesses-20180606-h111ca>, accessed 3 August 2018. |

| 4 | See The Jiahao Group official website, <http://www.thejiahaogroup.com>, accessed 31 July 2018. |