In 2014, Australian filmmaker Sam Zubrycki was in a record shop in Cali, Colombia, when he heard a voice on the stereo unlike anything he’d ever heard before. ‘It was so mysterious, so powerful, so strong,’ he tells me. ‘You could hear so much heartbreak and so much emotion – in the voice, in the arrangements, in the instruments.’

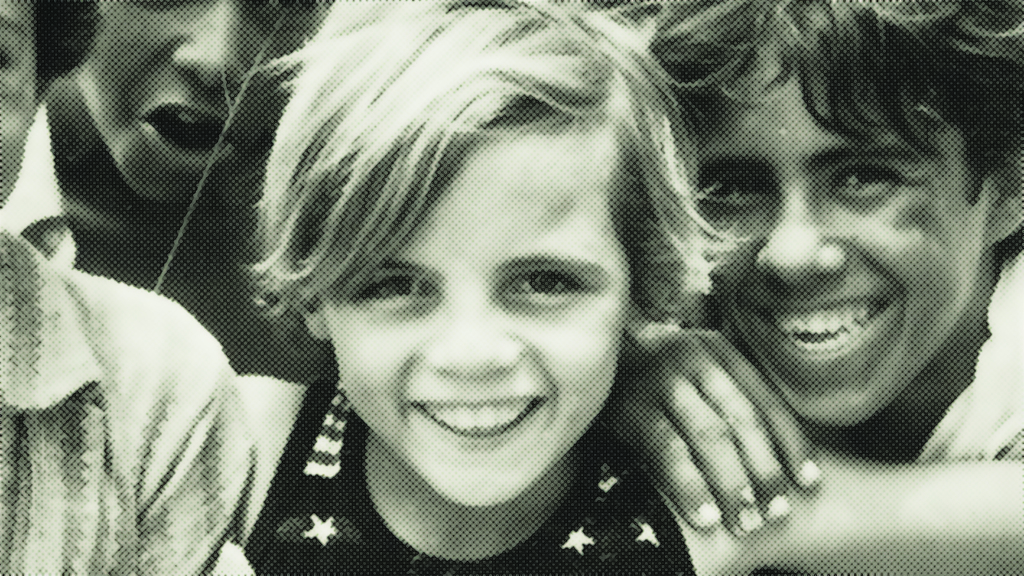

The voice belonged to an eleven-year-old boy named Miguelito, who grew up in one of Puerto Rico’s poorest neighbourhoods; the song was ‘Payaso’, written by Puerto Rican salsa composer Raphy Leavitt; and the recording was made in New York City in 1973 by Harvey Averne, founder of Coco Records and one of the most successful producers in the history of Latin music. Within a year of the album’s release – and after a concert in Madison Square Garden before a 20,000-strong audience – Miguelito had disappeared. Rumour had it that he’d died in a car accident.

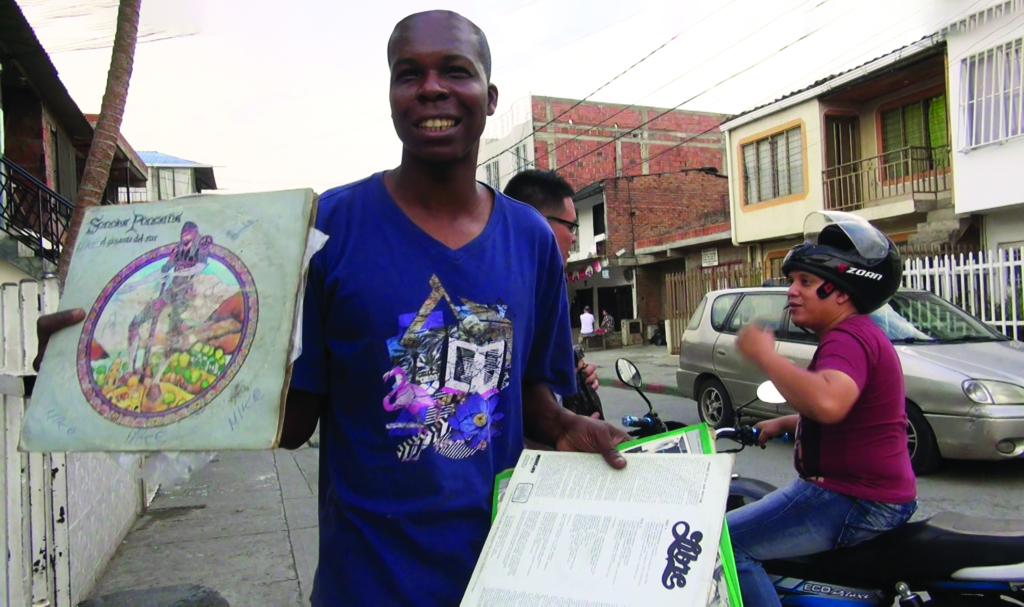

Zubrycki, who studied classical trumpet at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music and editing at the Australian Film Television and Radio School (AFTRS), was in Colombia travelling, thinking about making a film and pursuing his fascination with Latin music. The trip involved long stints in Cali, the widely acknowledged global capital of salsa,[1]See Hugh Thomson, ‘Rhythm Nation – How Cali Became Salsa Capital of the World’, Financial Times, 11 January 2019, <https://www.ft.com/content/9dc0ba04-126d-11e9-a168-d45595ad076d>, accessed 13 August 2020. where he spent time hanging out in record shops, chatting with record collectors.

When he heard Miguelito sing, a light came on, musically and filmically. ‘I was looking for a story that would help me enter the world of music and culture I was experiencing – and Miguelito gave me that path,’ says Zubrycki.

When I came back to Australia, I researched as much as I possibly could about him and all the musicians who played on his record, and came up with a plan that would allow me to make the film a reality. Eventually, I got in touch with Harvey and one thing led to another.

The resulting documentary is Miguelito: Canto a Borinquen (2019).[2]The film’s subtitle translates to ‘Song to Puerto Rico’, ‘Borinquen’ being the indigenous Taíno name for Puerto Rico and meaning ‘land of the brave lord’. See Ray Quintanilla, ‘Try to Understand: On the Island “Borinquen,” Puerto Ricans Are Different’, Orlando Sentinel, 9 May 2004, <https://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/os-xpm-2004-05-09-0405090141-story.html>, accessed 13 August 2020. The film will be available on DocPlay in late 2020. In essence, the film is a quest to find out who Miguelito was, by way of a journey into his world – through the musicians who knew him, the relationships he developed, the places where he spent time and the music that shaped him.

‘My big inspiration was Buena Vista Social Club [Wim Wenders, 1999],’ says Zubrycki.

Initially, I thought the story of Miguelito was just, in a sense, a beautiful tragedy. I couldn’t find out anything about him, so the question was: How do I tell the story of this boy when there is no archive, apart from a few photos and his music? I thought I would paint a portrait, made up of a series of stories, about the people who were around him at the time.

What the director wasn’t prepared for was the discovery that Miguelito’s disappearance was not as clear-cut as rumour had suggested. As a result, the film was drawn into much more unpredictable territory than the perhaps more straightforward narrative of a gifted young singer who made a popular record then died accidentally. Instead, Zubrycki found himself venturing into the dynamic between producer and singer – inevitably immersed in the complexities of the broader relationships between music industry and artist, and between the United States and Puerto Rico. Along the way, he captured the myriad ways in which salsa has evolved across nations.

‘I made three trips altogether,’ Zubrycki says.

In 2014, I went to New York City, where I met Harvey; and Puerto Rico, where I met some of the musicians who played on Miguelito’s album. But it didn’t work out so well. It seemed that no one knew anything and no-one wanted to help. All my leads were dead. Still, I had enough material from Harvey’s stories that I could start writing and thinking about how the documentary could be told – if I could tell it.

In 2016, I went back to New York, Puerto Rico and Colombia. That was the big trip when everything really happened. I made a lot of friends along the way who helped me out, such as cinematographer Hanley Zheng, who I studied at AFTRS with, […] even though a lot of people were also like, ‘Why is this guy from Australia calling me about a record made forty years ago?’ There was a lot of curiosity and surprise about the whole process.

In 2018, I took […] a pick-up trip to get the bits I really needed.

In Miguelito: Canto a Borinquen, Zubrycki ensures the viewer travels alongside him, prioritising a realistic portrait of his experience as filmmaker over either a concocted dramatic structure or an expository, journalistic approach. The documentary begins just as its director’s experiences did: the viewer first meets Miguelito through his voice and a handful of archival black-and-white stills. In the opening shot, a close-up of the boy’s face fills the screen as he sings:

Feeling this anxiety, and thinking that you’re mocking me

What a way to pay, making others laugh at me

Clown, yes … I’ll be a clown

Who’s forgotten himself and has to pretend.[3]Lyrics translated from the original Spanish by Shana Heslin.

As the film unfolds, the viewer learns of the stories behind this voice, just as Zubrycki did, through increasingly revelatory conversations – from fragments of memory conveyed in vox pops with people in the street in Cali who remember Miguelito’s songs to interviews with musicians who played on his album to intimate discussions with his mother and sisters.

Throughout, the two constant characters around whose relationship the film revolves are Miguelito, who, having disappeared, is unable to speak for himself; and Averne, who speaks through numerous interviews. It is a relationship that becomes more and more complex – and, possibly, troubling – as Zubrycki pursues more and more leads. However, rather than taking a position in favour of either character, the documentary presents multiple perspectives. The director explains:

I really wanted to sit on the fence. That was a deliberate decision. I wanted people to think about what occurred between this somewhat innocent kid and this somewhat innocent producer […] I didn’t feel like it was my place to make judgements about what happened. It’s a film about them, and about things that took place in a different place, in a different time.

I have a lot of affection for both of them. I understood how Harvey was feeling, and I understood how Miguelito’s family was feeling. I thought, ethically, this film isn’t about me imposing myself on their story. It’s more about helping them to tell their part – and to heal.

The worlds that shaped Miguelito and Averne are captured not through journalistic facts and figures or didactic statements, but rather through a patchwork of human encounters with the camera.

Even though Zubrycki avoids taking sides, his act of making the documentary has a profound impact on the subjects, as well as their relationships with one another and with the way they see the past. After all, it is his camera that reignites contact between Averne and Miguelito’s family following nearly five decades of silence. By this time, Averne is in his late seventies and, he says, has long believed the rumour that Miguelito died in a car accident. However, Miguelito’s mother and sisters, living in Puerto Rico, know this to be untrue – and the film provides them with an opportunity not only to say what happened, but also to confront Averne with it. Zubrycki says,

For Miguelito’s family, I think it was really healing. I think you can see that […] For Harvey, it was quite confronting […] He felt that he had tried to do a good job. He had been so attached to Miguelito the artist and not the human, not the whole situation. I think he’s such a driven man – it was hard for him to separate that, and I could see where he was coming from. I really felt that.

When [Harvey and Miguelito’s family] met, there was a huge misunderstanding, and, in the end, there’s a big question mark. It’s sad and confronting, but it’s also uplifting and curious. There are all these different emotions, and that’s just how the situation is.

Intensifying this complexity is the broad scope of the film. Although the plot gets its drive from the mystery of what happened to Miguelito and its drama from the relationship between Averne and Miguelito’s family, Zubrycki is just as concerned with the musical and cultural worlds the two protagonists inhabit. ‘Salsa really is a New York thing,’ says Averne in voiceover early on, as the camera flits between historical scenes of New York City in the 1960s and 1970s, from street footage to the Statue of Liberty to nightclubs filled with dancers. ‘When you listen to New York salsa, it’s hard. You hear the traffic; you hear the taxis; you can feel the tall buildings; you can feel the busyness.’

As these urban scenes give way to archival footage of Puerto Rico’s beaches, sunshine and outdoor concerts, Averne’s voiceover echoes the contrast:

If you listen to Puerto Rican salsa, it’s more ‘island’ feeling. The way they play is the way the culture is down there. It’s just a happier, less frantic, less hard culture. I can hear it in the music. Music is the beat of the island. Palm trees, ocean, white sand, beautiful women, pina coladas. What’s bad, Sam?

On the one hand, these are perceptive descriptions of salsa’s manifestations in different cultures; on the other, they describe the two worlds that collided when Miguelito and Averne met, with Averne’s idealistic views of Puerto Rico perhaps implying – or even explaining – his lack of awareness of his influence on Miguelito. While both were passionate about the same music, it played a different role in each of their lives. At the point of their first meeting, Averne was a successful producer who came and went from Puerto Rico freely, enjoying its slow-paced lifestyle as he pleased. Miguelito, in contrast, was an eleven-year-old who busked in the airport in order to financially support his entire family. The worlds that shaped Miguelito and Averne are captured not through journalistic facts and figures or didactic statements, but rather through a patchwork of human encounters with the camera, which together create a multifaceted, kaleidoscopic viewpoint. ‘I was adamant that the film wouldn’t be just about the reunion of Harvey and Miguelito’s family,’ Zubrycki insists. ‘It’s just as much about culture and music.’

The camera cuts deftly between moving cars, homes, recording studios, record shops, nightclubs and outdoor concerts in Colombia, Puerto Rico and New York, taking the viewer beyond the final products of concerts and albums and into the lives of the people who create them. In a kitchen in Guánica, Puerto Rico, the viewer watches trumpeter Nelson Feliciano as he plays a solo – while his grandchildren dance in the background – before recalling Miguelito’s Madison Square Garden concert as a ‘beautiful’ one, in which the boy handled the crowd ‘as if he was a general’. In a record shop, master timbalero and percussionist Nicky Marrero – who played with the Fania All-Stars, Eddie Palmieri and Joe Quijano, among other big names – warns that Latin music has ‘many, many rumours’. In Nublu, a crowded live-music club in New York City, singer Erica Ramos of Latin soul band Fulaso introduces Averne as a person to whom she must give ‘a special, special thanks’, lauding his sixty-year career in the music business and his production of the first Latin album to win a Grammy, Palmieri’s The Sun of Latin Music.

First and foremost a portrait of a gifted young singer and his relationship with the producer who brought him momentary fame, Miguelito: Canto a Borinquen is also a rich tapestry of music and culture in three contrasting places – Colombia, Puerto Rico and the mainland United States – over more than sixty years. It’s immersive rather than expository, and sweeps the viewer into the filmmaker’s journey, along with the many musicians, songs and relationships he encountered over five years of filming – conveying through sound, sense and feeling a complex and intense world. Perhaps its impact is best portrayed by Zubrycki’s own description of bringing the film to Miguelito’s home town:

We screened the film to Miguelito’s family in the project where he grew up in Puerto Rico, which is supposed to be this rough, tough place. Suddenly, all his friends started to emerge – people I’d never met during the filmmaking – and they were so touched by the film […] It was a really emotional, beautiful screening.

Endnotes

| 1 | See Hugh Thomson, ‘Rhythm Nation – How Cali Became Salsa Capital of the World’, Financial Times, 11 January 2019, <https://www.ft.com/content/9dc0ba04-126d-11e9-a168-d45595ad076d>, accessed 13 August 2020. |

|---|---|

| 2 | The film’s subtitle translates to ‘Song to Puerto Rico’, ‘Borinquen’ being the indigenous Taíno name for Puerto Rico and meaning ‘land of the brave lord’. See Ray Quintanilla, ‘Try to Understand: On the Island “Borinquen,” Puerto Ricans Are Different’, Orlando Sentinel, 9 May 2004, <https://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/os-xpm-2004-05-09-0405090141-story.html>, accessed 13 August 2020. The film will be available on DocPlay in late 2020. |

| 3 | Lyrics translated from the original Spanish by Shana Heslin. |