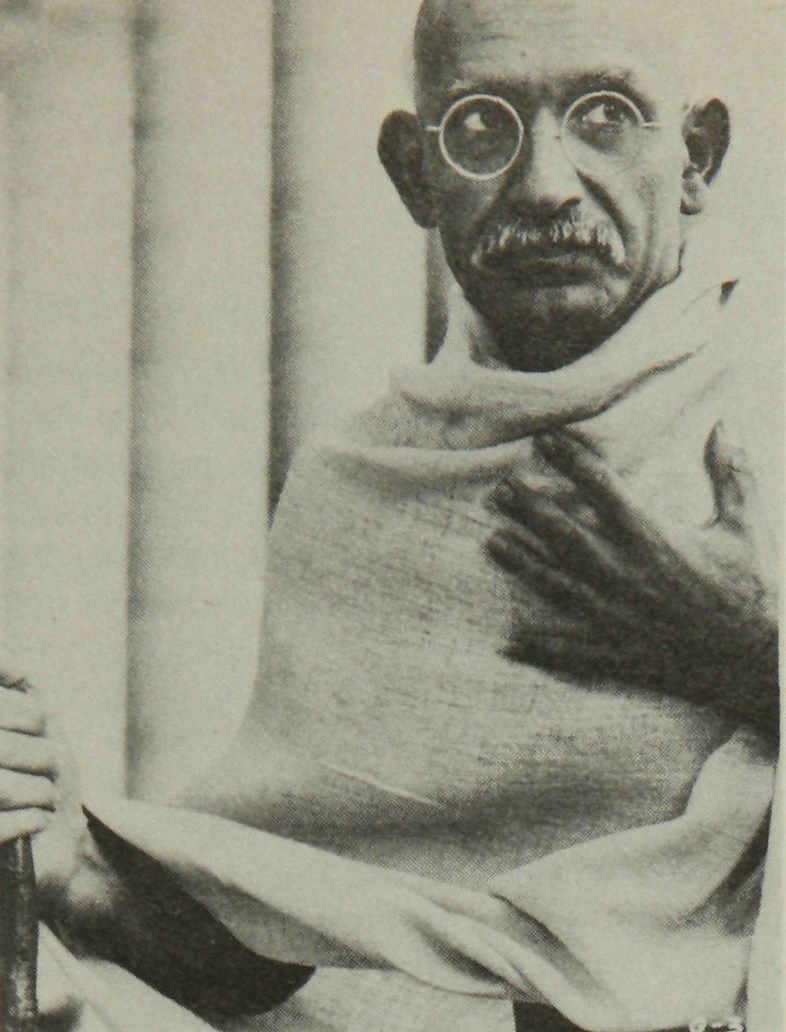

Metro: How do you see Gandhi – as a spiritual leader, an eccentric, an astute political leader … ?

Kingsley: Well, researching him and also remembering what Pandit Nehru said to Attenborough 20 years ago now, I had to aim for a balance. It was like a juggling act or a tightrope, trying to maintain a balance between all the three things that you have rightly mentioned. Nehru was very insistent that Richard should not portray Gandhi as a Saint but as a man amongst men. I think that in this case the story teller’s responsibility is to enlighten, entertain and provoke with the story of a man who lived and worked amongst his fellow man, rather than someone outside our realm of comprehension.

My interpretation is based on the confines of the script and my research with the script is also based on Attenborough’s aspirations as a film director and his sensitivity to history. So we conspired to present something that would make him tangible to today’s generation and today’s struggles. And I think it’s more appropriate and more an honest reflection of history, too, to present him as a political genius, rather than a collection of eccentricities or a spiritual leader.

We do have spiritual challenges to face in our society. Eccentricities, of course, are mushrooming all over the place in terms of fringe religions, diet fads and all that sort of thing. They are, in a sense, prolific symptoms of a deeper anxiety which probably has its roots in our politics and I think that is where Gandhi has hit. I think it’s fair to say that we did concentrate our energies on the remarkable political achievements that the man made. He made them by appealing to what we call our conscience. Some people could call that our spirit, so I think that there is not a hiatus between the spiritual and the political, but the ideal bond, the ideal balance between the aspirations of our conscience or our spirit and the aspirations for our society politically. I think Gandhi struck a brilliant balance between the two and that probably is the heart of his genius.

Metro: How important is it for our society to have heroes?

Kingsley: Whether it’s important or not, we will always create them for ourselves. Every single generation has created its sacred monsters and its heroes. I think it’s inevitable. We have a need, a curiosity, almost, to explore that which we think is outside us, and this brings me back to Gandhi not being a myth and not being a saint, but being a hero who constantly stayed within the framework, the silhouette of a human being. Those kind of heroes, I think we need very much. The hero who pits body, will and conscience against that which is intolerable.

Metro: How did the Indian people react to you?

Kingsley: Very positively. Very positively indeed. One is very vulnerable when one presents one’s portrait to the family, friends, lovers and followers of the subject of that portrait. Richard and I were co-authors of a portrait called Gandhi and we used to present it on location and hope that the appropriate response would be provoked in our extras, in our co-authors, in everybody that was there. We always ran the risk of presenting this portrait and people saying, “That’s interesting”, and that would be it.

Fortunately we provoked a response that was far more positive, excited, emotional, very gratifying. At first a little overwhelming and daunting. Until I learnt that part of the possibility, part of my responsibility to the role was to learn to cope with that kind of response gracefully and articulately and responsibly as an actor. It was my very minor contribution to the way Gandhi had to cope with massive crowd adulation, and he always disarmed, defused that adulation by saying, as you guided me towards saying very rightly earlier on, I’m not a saint, I’m a politician. I’m a man. And there were many gestures of adulation towards him that he had to very carefully defuse and disarm and I had one or two tastes of that myself, so that it taught me a great deal about the private and the public struggle of the man.

Metro: What scenes were the most memorable for you?

Kingsley: Reading the script before we started I had singled out scenes that I felt would be the ones that would be memorable, but as very often happens in life, if you pre-rehearse a meeting, an acquaintance, a moment, it always surprises you. It’s never how you imagine it’s going to be in your mind. So that, scene after scene, day after day, each was the most important scene in the film. I remember saying to Richard, “Isn’t it odd? I never thought that this scene would be important” and Richard said to me, “Neither would I. I didn’t think it would be as important as it is today.” Every day we had to focus our attention on whatever scene we were doing and it had to be the most important piece of the mosaic as were putting in place on that particular day.

Metro: How did you make the transition from stage to the film set?

Kingsley: I had the sort of discipline to cope with it and not be totally emotionally overwhelmed by it and go slightly loony at that kind of exposure and those kind of experiences. It almost happened every day and I just had to immediately accept them, acknowledge them kindly and gratefully and then put them into their right perspective and allow them to feed the work. And I think a great deal of our film was made possible by the people who were totally behind us all the way.

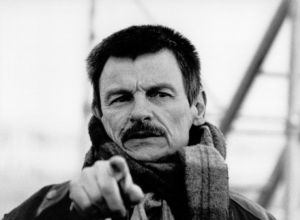

Metro: Was it difficult to create the very large spectacle scenes, like the funeral scene?

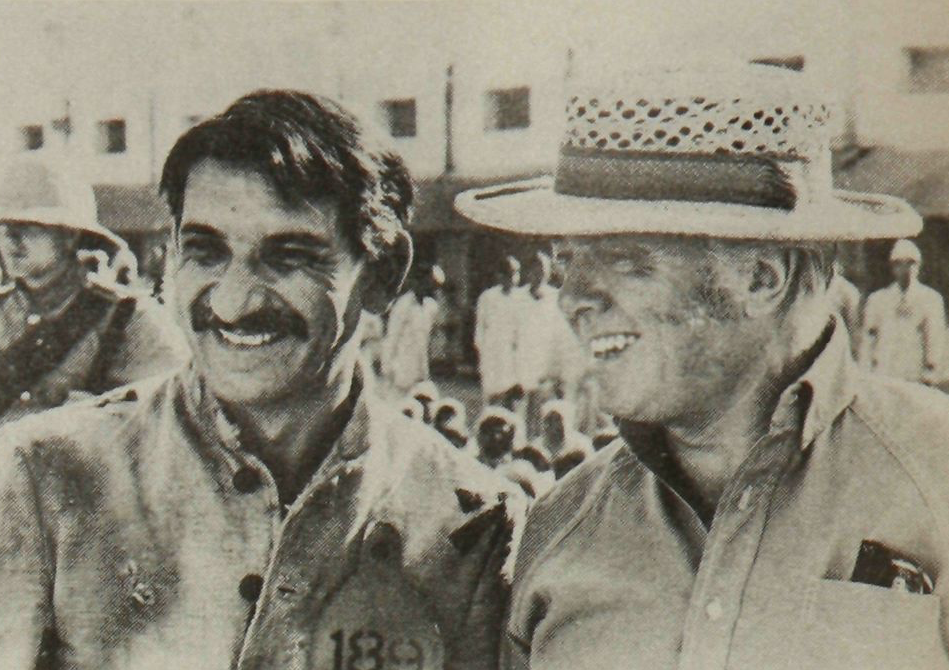

Kingsley: Technically that was very difficult. I think about 90,000 people were paid on that day, so we knew they were coming. They were brought in by bus. I was at the meeting prior to the funeral scene and I said to Richard, “I want to watch the funeral scene because I’ve always had a fantasy about watching my own funeral and I thought that I might be able to participate in this fantasy.” He said, “Yes but you must wear a big hat and dark glasses and come and stand next to me on the camera dolly and watch it.”

We placarded the town and invited people to participate in a recreation of history. Coincidentally this scene was shot on the day of the 33rd anniversary of the funeral. It was our last day in Delhi and we had to do it then. I believe another 300,000 people arrived to participate so we then had 400,000 people. That’s the number that you see on the screen in the film. It is colossal as you know.

I was on my way out of the hotel when Richard starting filming, using a dummy that Tom Smith (my make-up man) had modelled on me. I used to go down to the cellar of the hotel and model for the dummy. I knew that this was my day off, this was the one scene I would not be involved in. But then, a telephone call came, Richard was not happy with the close-ups. Would I please get into deceased make-up and come out and lie under the flag, guarded with flowers with a mark on my forehead.

I put a great store by preparation as an actor. I like to be prepared. I was not prepared for that scene at all. Fortunately I’d done a lot of yoga in India and had done on that day. My yoga teacher had taught me to go into a stillness that was not sleep, because you can do all sorts of things in your sleep – roll over and scratch – but to go into a state of almost suspended animation. Fortunately, blessedly, I was allowed to put this exercise into practice because I went onto the back of the lorry in front of 400,000 and I didn’t move a muscle for 31/2 hours.

As a technical exercise I would single that one out as the most difficult. At the end I was very stiff because I hadn’t moved. So I sat up very slowly. I made a physical gesture of thanks or greeting – by simply putting my hands together and bowing to the four corners of the crowd. One person stopped to applaud and I thought that this was the beginnings of the derisive slow hand clap, but fortunately it wasn’t. They all then started to applaud, chant and throw the flowers which were left over from the scene. It was the most gratifying round of applause that I’ve ever received in my life as an actor. Very generous, because they could have just hooted me off the film set.

Metro: How do present day Indians view Gandhi?

Kingsley: The government entertainment tax has been removed on the price of a ticket to go and see Gandhi so that this is an indication that there is an appetite for him. I think there is an interest that’s reawakening in India and also a reversal of the process of deification that almost inevitably takes place in India. There were, when we were there, strange paintings or photographs of Gandhi in village houses, that have their place next to Vishnu and Krishna and other deities and we could see, to our dismay, that generations to come would scarce believe that such a man walked the earth. I think what the film’s done – the literature, the educational programs and the research – has helped to throw that process into reverse and that now India is realising again that only a few years ago did this man achieve the colossal break-throughs that he did.

Metro: What relationship did Indira Gandhi have to the funding and pre-production of the film?

Kingsley: She read the script and Richard asked her for her response and she said, “I am not going to approve this film,” and naturally his heart plummeted to his boots. She then followed that sentence through immediately by saying, “because it’s not for me to approve this film. All I’m doing is reading it as a work of art. As a film, it’s appropriate. That’s all, given who the film’s about.” She said, “I think it’s entirely appropriate and it’s a marvellous script. If I may, I would suggest that certain terms, family terms, in the earlier sequences between Gandhi and his wife could be slightly more accurate.” In other words, she would never address him as that, she would address him like that. She would approach him like this and not like that. She would give him his food like this and not like that. I mean, marvellous domestic details that she contributed to a small area of the film. And there was a place name, a stupid inaccuracy about the name of the village that she pointed out. That, in terms of her guidance, was her only contributions. She gave Indian Government backing, financial backing to the film. This has now been repaid. The enormous profits, thanks to the success of the film, have paid back the loan and gone straight back into the Indian Film Industry. Logistical, tactical support from the police, the military, the road departments, the Listed Buildings and Monuments Department, allowed us to put a cardboard statue of King George V back in Delhi for the shooting of the funeral. Extraordinary things happened. All with her permission and under her protection. So her contribution was enormous. There would be no film without Indira Gandhi’s contribution.

Metro: The film has been seen as a statement opposing British colonialism. Do you think this is so?

Kingsley: It’s a film opposing the concept of one culture dominating another by force. If this is part of the British history then we must also acknowledge it. It’s a film studied by the aristocracy of the English Theatrical profession. Not only is it directed by Sir Richard Attenborough, but its cast includes Sir John Mills, Sir John Gielgud, and Sir John Clements. The ‘Sirs’ are endless in it. I think it’s a reflection on the maturity, hopefully, of English society, that we can make this film. It’s a kick against oppression. It’s a kick against tyranny.

Metro: In many ways, because of the aristocracy of British Theatre and the co-operation of Indira Gandhi, many people are sceptical about the story of the film. Do you have any response to that?

Kingsley: I would say that their scepticism, as in the Indian press, is not founded and they should see the film with an open mind and come away with a very appeased heart. The Indian press had those misgivings, grave misgivings, prior to seeing the end product. They all published leading articles in The Times of India and the Indian Express the following day saying, “We are sorry that we ever hurled missiles at this project because it is very faithful to history, very honest, full of integrity.” I am only quoting what they’ve said, so that any fears that people may have, I hope will not be an impediment to them seeing the film and enjoying it. I think it’s a very honest piece of work.