Life isn’t easy for the residents of Argokhi, Georgia. Their small rural village huddles in the foothills of the imposing Caucasus mountain range, where the natural beauty of the terrain is mostly untouched by modern intervention. This is a place that seems to resist the pull of technology and the other trappings of contemporary life. Most villagers live hand-to-mouth, working the land to produce food for themselves and their neighbours. Animals are either slaughtered for meals or sold on for profit. The land itself is diligently tended using agricultural practices that date back to the Middle Ages; as one resident explains, ‘We all grow our own wheat and mill it into flour. You can’t make a living out of working in the village. We work just to live.’

In the Land of Wolves (2018), writer/director Grace McKenzie’s sophomore documentary feature,presents a fascinating snapshot of a community that appears to stand outside of time. Yet, as the film shows us, there is a universality to the human condition that time and place cannot alter. Building on the intimate filmmaking of McKenzie’s award-winning debut, Audrey of the Alps (2012), In the Land of Wolves also exudes a gentle poignancy that takes its cues from the unhurried rhythms of slow cinema. A broad definition of that mode of filmmaking will usually note features like ‘the employment of (often extremely) long takes, de-centred and understated modes of storytelling, and a pronounced emphasis on quietude and the everyday’.[1]Matthew Flanagan, ‘Towards an Aesthetic of Slow in Contemporary Cinema’, 16:9, vol. 6, no. 29, November 2008,<http://www.16-9.dk/2008-11/side11_inenglish.htm>, accessed 19 February 2019. Certainly, the film’s effect on the viewer is gently hypnotic as it homes in on details: a donkey’s hoofs punching out little grooves in the snow, a hand caressing a newborn calf, fingers kneading dough. Produced by McKenzie’s father, Brian, with assistance from Screen Australia, this is a lucid, assured cinematic work from a talented young Australian director.

In and out of time

In the Land of Wolves uses the rhythms of the seasons as a framing device, eschewing a formal narrative structure. It tracks the lives of a handful of residents over the course of a year, dropping in and out of their lives like an old friend. McKenzie refers to the film as ‘a pastoral symphony’,[2]Grace McKenzie, in ‘About the Making of In the Land of Wolves’, Brian McKenzie Film Productions & Screen Australia, In the Land of Wolves press kit, 2018, p. 5. a lovely description of her freewheeling approach that responds to the vagaries of nature and to the relationship between it and the film’s subjects. After all, the seasons shape the Argokhi villagers’ daily toil, determining the cycles of growth and harvest that provide them with food and income.

In the Land of Wolves uses the rhythms of the seasons as a framing device … McKenzie refers to the film as ‘a pastoral symphony’, a lovely description of her freewheeling approach that responds to the vagaries of nature and to the relationship between it and the film’s subjects.

Frenchman Jean-Jacques is an expatriate living in the village; he sells his artisanal bread at a weekly market stall in the capital city of Tbilisi. He brings contemporary methodology to the way that he farms and produces – biodynamic techniques that would make any urban hipster proud. European students come to volunteer at his farm. While the presence of these young travellers might seem strange in such an isolated rural location, Argokhi, in fact, welcomes outsiders. The village’s population is primarily composed of Georgians and Ossetians; McKenzie’s film shows us how the two ethnicities are harmoniously blended, often via marriages. But, while the lands of North Ossetia remain under modern-day Russian control, Georgia gained its independence from the former Soviet Union in 1991, with South Ossetia contentiously subsumed into it. Tensions and violence over territory there, as well as in other parts of Georgia, still take place. It’s unsurprising, then, that the Ossetian population is not-so-happily integrated elsewhere in the country.[3]See Giorgi Sordia, Ossetians in Georgia: In the Wake of the 2008 War, European Centre for Minority Issues, working paper no. 45, September 2009, pp. 4–15, available at <https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/106675/working_paper_45_en.pdf>, accessed 18 February 2019.

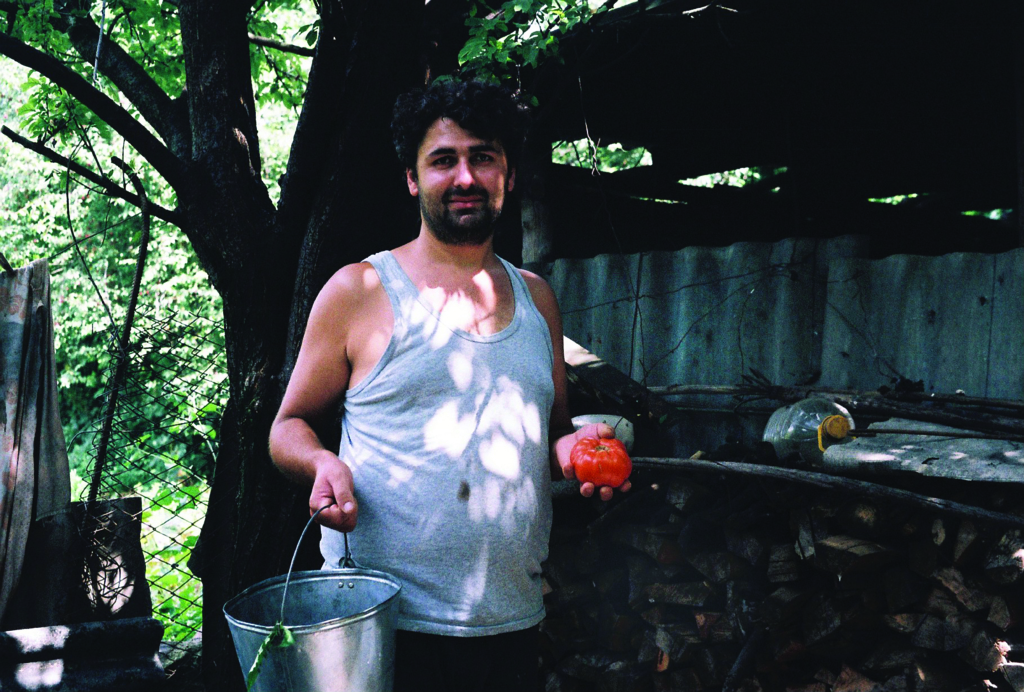

Sveta, Jean-Jacques’ Ossetian neighbour, acts as a friendly go-between connecting farming families. At times, her function in McKenzie’s film recalls that of a solitary Greek chorus, as she elucidates the actions of other villagers or provides context for their struggles. But Sveta’s commentary becomes particularly enlightening when she speaks about the predicament of Jimmy, a deaf turkey farmer who can’t speak but who has a preternatural kinship with animals. Gradually, Jimmy’s story becomes the compelling centrepiece of In the Land of Wolves. Despite his disability and the isolation that this creates for him within his community, his experiences offer a bridge between the world depicted in the film and that of foreign audiences.

Jimmy is arguably the most sympathetic figure in the documentary, and there is a comforting familiarity to his circumstances that transcends the very specific (and, in many ways, otherworldly) setting and subjects that the film tracks. Having recently returned to Argokhi after a failed marriage, Jimmy is caught between the pull of family, the village and an independent life. He misses his daughter, who remains with her mother in the city. Devoted to supporting his family, he proudly grows the largest turkeys in the region so that he can make a good profit from their sale. Yet his own identity seems to oscillate between pragmatic, hardworking villager and lonely young man yearning to find his tribe.

Ano, Jimmy’s kind, down-to-earth mother, worries about her son and wants him to settle down with a new wife. But Otar, his father, is existential in outlook – the result of a life in which uncertainty is a dominant keynote. He personifies the stoic temperament of the villagers with reflections such as this:

We are tormented. Sometimes, we have joy in our life; sometimes, we have tragedy. One cannot have a life without such things. No smooth road exists. One just has to stumble somewhere.

Disconnection and connection

When McKenzie arrived in the village, her initial impression of it was that it was an idyllic refuge where old ways of living were preserved rather than destroyed. However, on closer examination, a different picture gradually emerged:

In reality life is harsh in the village and there is a battle to make ends meet. It would be naïve to think that the residents do not know what is going on elsewhere. Everyone dreams of living in the city with all the modern appliances. The young are bringing in cars and have a reckless obsession with the [W]est. After the war with Russia, America is favoured and graffiti at the bus stop reads ‘Buy U.S.’ The elderly are disappointed with the shift but tired of working hard. The young want to leave and the old cannot look after themselves. Pressure mounts for consumer items and the haphazard network of subsistence growers is not able to deliver what the young people want.[4]Grace McKenzie, in ‘About the Making of In the Land of Wolves’, op. cit., pp. 4–5.

The importance of communication for human survival and for the preservation of hope is a subtle but pervasive trope in In the Land of Wolves. The farming families are a self-supporting network, a real flesh-and-bones community that functions on physical interaction and shared labour.

This idea of an intergenerational disconnect is significant. The older villagers aren’t plugged in to the technological networks that are so ubiquitous in the West. Some of the younger residents have a small taste of these forms of communication, and they want more. While the film largely follows the older villagers, there is a brief glimpse of this disjuncture when we see Ano puzzling over Jimmy’s night-time online chats, wondering how on Earth he could stay up so late on his computer. Perhaps, for Jimmy, online communities might be especially important, but for all of the other subjects in the film, EM Forster’s epigraph ‘Only connect!’[5]EM Forster, Howards End, The Floating Press, Auckland, 2009 [1910], p. 335. resonates sharply. The importance of communication for human survival and for the preservation of hope is a subtle but pervasive trope in In the Land of Wolves. The farming families are a self-supporting network, a real flesh-and-bones community that functions on physical interaction and shared labour. In contrast to the digital relationships of online worlds, here is a place where communication is a pressing material commodity.

Interestingly, communication posed extradiegetic hurdles for the filmmakers. Brian McKenzie recounts, for instance, that distance was an issue:

For two years, our collaboration took place from opposite sides of the globe – Grace was in Bristol and I in Melbourne. We were in the village together four times during production (and again during post production), often meeting on the way in Istanbul.[6]Brian McKenzie, in ‘About the Making of In the Land of Wolves’, op. cit., p. 6.

More pressingly, communication posed challenges due to the complex language barriers. When shooting footage of the villagers, Grace McKenzie could only speculate as to what they were saying to one another. Adding another layer of difficulty was the fact that some spoke Georgian while others conversed in Ossetian. And then there was Jimmy, who expressed himself using sign language. As a result, the filmmakers required an elaborate chain of interpreters to pin down what the subjects were saying. In a way, this process replicates Jimmy’s experience, as a deaf man, of being an outsider in a predominantly hearing world. At the same time, it reaffirms the capacity for reciprocal understanding despite differences – a very moving and humbling comment on the expansiveness of human connection.

Some of the loveliest moments in In the Land of Wolves celebrate the residents’ intimate connections. McKenzie makes wonderful use of a series of tableaux featuring family members; these images are highly constructed and static, recalling photographs, yet she also includes some footage of her subjects preparing to get into frame, jostling each other for prime position or smiling nervously at one another. Yet, despite their artificiality, these staged images, much like the rest of the film’s scenes, are nevertheless anchored in the moment. Complementing these visuals, sound is used to convey a sense of place and of Georgian culture – particularly in the form of diegetic music and singing by locals. Together, image and sound reinforce the film’s organic sensibility in a way that is both moving and insightful.

From farm gate to plate

Death is never too far away in Argokhi. The precarious balance between life and death is a part of the villagers’ largely unmediated interaction with the natural world. In contrast with the West (and with cities more broadly), where death is a latent presence, here, the practical reality of death is unmuted.

The film opens with a confronting sequence that demystifies the process of birth; depicting a calf being unceremoniously dumped into a cruel and indifferent world, it discards any romantic connotations we commonly associate with new life. The calf struggles to feed from its mother, and needs Jimmy’s help to stay alive. The proximity to death is immediately emphasised – and this theme becomes a recurring trope in the film. Some baby chickens thrive while others don’t last long enough for a first breath. The villagers chase a pig around before ritually slaughtering it for a traditional feast. Otar tells us his donkey has had a sad life as a mother: two of her offspring were stillborn. And, when Ano’s cousin passes away, we are invited to the funeral.

Arguably, this acceptance of the arbitrariness of life and death partly comes from the subsistence farmers’ pragmatic relationship to animals. Otar recalls his mother scolding him as a boy for protesting against the slaughter of a pet lamb. The dissociation between food source and food consumption that we in the West take as a given is, clearly, not part of the Argokhi consciousness. In fact, one of the film’s most interesting messages concerns this same unmediated relationship between agriculture and food consumption: it reminds us that our experiences with over-packaged supermarket products are a sadly sanitised reality. It offers us an opportunity to reflect on the enormous distance we tend to have between what we eat and its origins. Perhaps an appreciation of the provenance of our food might help us to consume more carefully, and to reconsider our relationship to animal products.

In the Land of Wolves brings us up close to the day-to-day minutiae of village life, with each season bringing its own hardships and pleasures. Beyond its old-world beauty, however, Arghoki is a place at a sociocultural crossroads. Much like the world it shines a light on, this film, too, is at a crossroads. Its Sydney and Melbourne film-festival sessions were warmly received, and, while it is showing for the first time in Georgia at this year’s CinéDOC-Tbilisi documentary festival, McKenzie is still on the hunt for a distributor. Mirroring her team’s difficult journey while making the film, this process hasn’t been easy. ‘[In the Land of Wolves] doesn’t have a driving story or clear theme, so it’s hard to describe, let alone sell,’ she explains. ‘It is a thoughtful film with a lot of heart and care, and audiences seem to appreciate it, but it’s a process to get it viewed.’[7]Grace McKenzie, email to the author, 8 February 2019.

‘Thoughtful’ indeed, but not just that – this is a thought-provoking glimpse into unseen lives that deserves to find an audience.

Endnotes

| 1 | Matthew Flanagan, ‘Towards an Aesthetic of Slow in Contemporary Cinema’, 16:9, vol. 6, no. 29, November 2008,<http://www.16-9.dk/2008-11/side11_inenglish.htm>, accessed 19 February 2019. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Grace McKenzie, in ‘About the Making of In the Land of Wolves’, Brian McKenzie Film Productions & Screen Australia, In the Land of Wolves press kit, 2018, p. 5. |

| 3 | See Giorgi Sordia, Ossetians in Georgia: In the Wake of the 2008 War, European Centre for Minority Issues, working paper no. 45, September 2009, pp. 4–15, available at <https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/106675/working_paper_45_en.pdf>, accessed 18 February 2019. |

| 4 | Grace McKenzie, in ‘About the Making of In the Land of Wolves’, op. cit., pp. 4–5. |

| 5 | EM Forster, Howards End, The Floating Press, Auckland, 2009 [1910], p. 335. |

| 6 | Brian McKenzie, in ‘About the Making of In the Land of Wolves’, op. cit., p. 6. |

| 7 | Grace McKenzie, email to the author, 8 February 2019. |