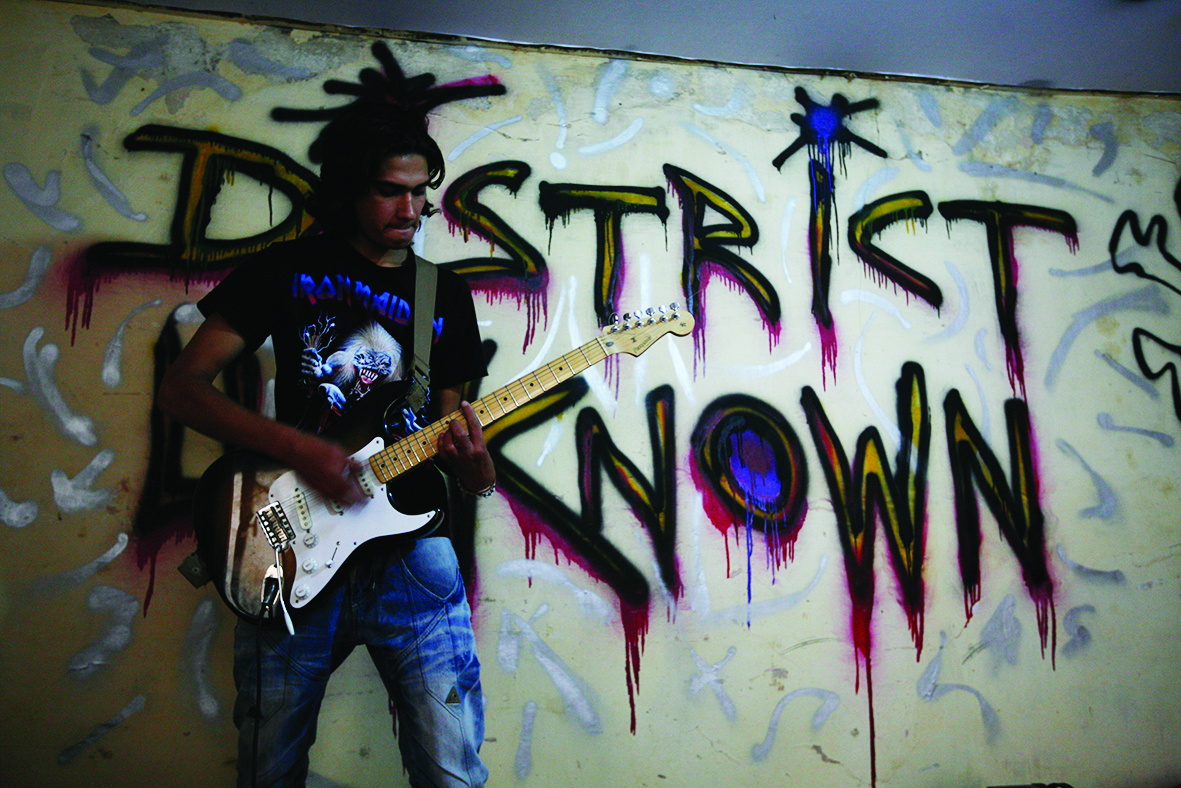

We see four men – lanky, floppy-haired, tufted with goatees – sporting Converses and Pink Floyd T-shirts. They play air guitar and air drums; they make the sign of the horns with their hands. They’re into Metallica logos, and they rehearse atonal noise in a graffitied basement riddled with spiders and mice. ‘Where did you learn to play drums?’ asks an off-screen Australian voice. ‘Nowhere,’ replies Pedram, the drummer.

Music documentaries have covered the myth of the lost, fallen artist before – Finding Fela (Alex Gibney, 2014), No Direction Home: Bob Dylan (Martin Scorsese, 2005), countless Kurt Cobain tales. They’re redemption fables, often. Australian filmmaker Travis Beard’s RocKabul (2018), however, follows an aspiring metal band from first rehearsal, to first gig, to final downfall. District Unknown was, in the early 2010s, the only metal band in Afghanistan, comprising Pedram, guitarist Qais, bassist Qasem and vocalist/guitarist Lemar. Rather than the music doco’s usual loci – the tour or the music industry – RocKabul’s backdrop is twofold: the bombs falling outside the band’s homes and gig venues in their war-stricken homeland, and the surging metal music scene comprising young Afghans seeking rebellion and belonging, identity and community.

Beard’s documentary begins with then–US president Barack Obama calling for more drones and a stronger military presence in Afghanistan. But RocKabul isn’t crafted from news archives or voices from outside Afghanistan, instead centring on street-level views of people living in the country and embedded in its rapidly changing culture, whom Beard captures while working as a photo- and video-journalist there. Alongside these, the documentary charts District Unknown’s aspirations, from playing the first major festival in Afghanistan since Soviet invasion to their attempts at an overseas tour as their domestic safety is threatened. ‘The religious police are just hunting for this kind of stuff,’ Beard told music website Louder in 2016.[1]Travis Beard, quoted in Rob Hughes, ‘Rock in a Hard Place: Why Are Iran and Afghanistan Jailing Metal Bands?’, Louder, 17 May 2016, <https://www.loudersound.com/features/rock-in-a-hard-place-why-are-iran-and-afghanistan-jailing-metal-bands>, accessed 14 October 2018.

In District Unknown’s early existence, they had no instruments, lacked musical knowledge, didn’t even know they needed to keep instruments tuned while rehearsing. Self-taught, they toiled away in secret, craving the guidance of foreigners as well as their practical assistance (much of the band’s early gear was purchased for them by expats who had access to internet shopping on Amazon). Musically, their initial efforts are described by one of their expat friends as ‘muddy stuff’, the musos dedicating themselves to finding new paths through metal and rock; as Lemar puts it, they had to learn ‘how to create Afghan music inspired by Western music’. By 2010, they had played their first gig in an expat bar – a self-declared failure. Nevertheless, they found a rhythm and a schtick for their performances, holding their first recording session and taking the first ever stage dive in the country.

By 2011, news reports were quickly spreading about hidden, fortified venues and expat bars across Kabul housing a small but burgeoning music scene.[2]See, for example, Ron Synovitz, ‘Rock Bands Playing “Stealth” Festival in Kabul, Despite Taliban Attacks’, Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty, 16 September 2011, <https://www.rferl.org/a/rock_bands_playing_stealth_festival_in_kabul_despite_taliban_attacks/24329799.html>, accessed 26 October 2018. District Unknown’s music had begun to resonate with other youth who were looking culturally to the West to leave behind the past. Also that year, Obama promised to remove most of the US’s remaining troops.[3]Mark Landler & Helene Cooper, ‘Obama Will Speed Pullout from War in Afghanistan’, The New York Times, 22 June 2011, <https://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/23/world/asia/23prexy.html>, accessed 26 October 2018. Domestic security deteriorated, and the band began wearing masks to their gigs – creepy, white, plastered designs that could have been born of a B-movie slasher – after hearing rumours that they had been called ‘irreligious’ by conservatives.

In Beard’s film, we see Lemar desert the band in search of stability, finding a quiet, married life in Turkey. ‘I’ll be glad to be alive,’ he says.

This is not my country anymore. It is a battlefield for drugs, for mafia and for money. It is my country, but it has turned into a battlefield and I don’t want to live in a battlefield.

He leaves suddenly, as many Afghans tend to when escaping the front lines. His band members send him video messages, and their sorrow at yet another separation from a loved one is palpable. But the group persists – in time, they secure a new vocalist, Yousef, and prepare for Sound Central, the first rock festival in Afghanistan in almost thirty-six years.

In these moments, Beard skates past the far more melancholy story at the centre of RocKabul. This may be because of his own role in District Unknown’s trajectory. With David Gill and Humayun Zadran, Beard created Combat Communications, an organisation that offers artistic and musical opportunities for Afghan youth. His contribution to District Unknown was as mentor, friend and promoter; and to RocKabul, as director, writer, cinematographer, co-editor and co-producer. When the documentary’s narrative begins in 2011, District Unknown is limited to using Beard’s house as a rehearsal space and venue. His presence in the film varies, and only gradually does the depth of his involvement become clear, with an unnamed, unseen woman’s voice only occasionally leading conversations. Documentary makers have always debated their own roles, and some of the most famous – like Michael Moore – tend to be forceful on-screen figures in their own works. They declare that role from the outset. But Beard never appears to ask the same sensitive questions, and the line between him and the work becomes increasingly cloudy as the film progresses. After all, the role of the photo-journalist differs markedly from that of the documentary maker.

During a conversation in Kabul’s District 10 in which the band are seriously assessing their safety and future, Beard pushes back when one member asks him to stop filming. There is no guarantee they can escape Afghanistan, and, even if they do, their families may remain jeopardised. Qais asks, pointing to various individuals, ‘What do we do if you are killed, or you, or you?’ Pedram argues strongly against continuing to perform in Afghanistan; standing up in his flannel shirt, he tells Beard, ‘Listen, seriously, you should turn off your cameras.’ Off screen, Beard replies, almost shouting, ‘Why, why, what’s the problem?’ Pedram reiterates, ‘I want you to turn it off,’ and the question comes, again: ‘Why?’ Pedram resolves the situation by leaving the room.

These types of scenes are bracketed in the film with wide shots of helicopters looming overhead, of visuals of gunshots sparking in the night – in other words, the film is careful in some moments to heighten the dramatic stakes by showing the band’s risky context, and insensitive to these same risks in others. Later, Beard asks Qais if he is marrying an Afghan-American ‘just to get a passport’. On occasions like this, Beard’s hectoring tone hardly speaks to the ethics of respectful documentary-making in communities that aren’t the filmmaker’s own, and is further complicated on others when his association with the band seems to endanger them, as at a gig in Mazar when the police ask, ‘Why is this foreigner guy with you?’

Beard’s involvement also casts a celebratory tone across the documentary that evades its murkier political details. By late 2011, Western media had caught wind of Afghanistan’s simmering metal scene. ‘Amplifiers in Kabul’, announced a Rolling Stone headline,[4]Daniel J Gerstle, ‘Amplifiers in Kabul’, Rolling Stone, 7 December 2011, available at <https://archive.is/da8yk>, accessed 14 October 2018. with reports in CBS[5]‘Afghan Youth Rock Freedom of Expression at Festival’, CBS News, 3 October 2011, <https://www.cbsnews.com/news/afghan-youth-rock-freedom-of-expression-at-festival/>, accessed 14 October 2018. and BBC[6]Tulip Mazumdar, ‘Rocking Kabul: Afghanistan Stages Secretive Rock Event’, BBC News, 4 October 2011, <http://www.bbc.co.uk/newsbeat/article/15151891/rocking-kabul-afghanistan-stages-secretive-rock-event>, accessed 14 October 2018. released just prior. It was the perfect ‘good news’ story amid an ailing, never-ending war and a novel, grand rationale for the occupation: the youth of Afghanistan had spoken, and they were adopting a distinctly American cultural form as an expression of Middle Eastern resistance. Here was a genre, having peaked and been taken for granted in the West, that was being crushed by oppressive regimes that loathe the US and everything it stands for. Beyond the music, metal came to stand as a symbol of freedom of expression, as rebirth in a cultural vacuum. The Rolling Stone article spoke gleefully of secret underground bunkers, entered by code word and approached by navigating endless police checkpoints on dusty streets. In the mosh pit, passionate youth weren’t just mindlessly headbanging but challenging closed-minded community elders, abusive fathers and religious overlords. Indeed, the title of RocKabul’s predecessor work, Martyrs of Metal (2014),[7]Hughes, op. cit. drives home Beard’s ideas even further.

The story is less spontaneous than it first appears, however. The Sound Central gig – which marks a triumphant climax in the doco’s narrative trajectory – was partly supported by the US Embassy,[8]See Monica Racic, ‘An Afghan Rock Festival’, The New Yorker, 20 September 2011, <https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/an-afghan-rock-festival>, accessed 14 October 2018. and endorsed publicly by its cultural affairs officer, who explains on camera that ‘the US Government is funding heavy metal’. RocKabul avoids any analysis of the reasons behind and implications of this US support, instead emblazoning the same ‘freedom’ narrative; it’s worth noting that one of the main organisers of Sound Central is Beard himself.[9]ibid. In this way, RocKabul’s promise of telling the story of subversive Afghan youths, through the voices of those youths, is disingenuous at best.

There’s a fascinating history, yet to be accounted for, surrounding this strange, sad, singular band, whose members scream ‘after the blast, after the blast, after the blast’ on stage. Despite never having been on a plane or to a gig outside Kabul, they emulate their musical heroes perfectly. While their self-declared aim is to make their own music with metal inflections, District Unknown’s tracks sound much the same as any metal we might hear on our car radios – System of a Down and Slipknot being the immediate Western parallels – and it’s difficult to discern if they indeed have crafted a new, localised subgenre melding various musical forms.

So where do they differ? The band’s anachronistic reference points may be jarring to Western viewers – the camouflage khakis and ultra-male headbanging seem culturally retrograde, even regressive, from the vantage point of Australia. Their songs may have typically metal-sounding titles like ‘Nightmares’, but District Unknown’s sense of rebellion comes from a deeper wellspring than that of Western teen dissatisfaction. The members of District Unknown are making music at a total remove from the genre’s original context; their own context is defined by survival in a decaying society that detests their existence. ‘Damn those who ruined our country!’ screams Lemar in 2011, introducing a song called ‘We’ll Stay’. The band members warn that Afghan society ‘will call you Satanists’ should you identify as a rock artist – and they’re not exaggerating. A Taliban judge, shown in the film, laments metal and rock as the music of infidels who have abandoned Islam: ‘Flames will come out of your ears on Judgement Day.’ But, while Western media tend to accentuate the religious and tribal chasms tearing at Afghan society, RocKabul almost accidentally takes the gravity out of the country’s cultural and generational differences.

The members of District Unknown are, after all, a group of youths who have experienced suicide bombings, public explosions, drone attacks, the fear of sudden death – war, in all its manifestations, in an invasion that has now lasted seventeen years. The irony is that, as the band’s fan base is seen growing over the course of the documentary, so does the possibility of a conservative backlash from authorities. After reactionaries throw stones at them at a gig outside Kabul, Yousef is taken to the police station, where he is held and questioned. In the aftermath, the band delete their Facebook page, dissolve for several months, and two of them cut their hair to meet traditional standards. In these ways, District Unknown’s aggression, their masculine postures, comes from that context of despair and uncertainty – from the rubble and the rockets of endless occupation and, as we come to learn, from the ever-hovering prospect of forced emigration.

But the group’s orientation to a political message becomes another fascinating yet mostly overlooked point: ‘We’re not trying to do a demonstration against the Taliban or against the government,’ says Qasem, arguing for a more oblique form of self-expression as rebellion. ‘We’re not those people. If we’re not talking about who we are and we’re not expressing ourselves, then we are dead.’ Debate rages bitterly among the musicians as to how proudly they should wear their nationality: ‘We are here to play our music, not give the history of Afghanistan, and that is all that matters!’ yells one band member to Lemar as they reunite with him to play in India. Likewise, the documentary invests heavily in the romantic idea of the rock band as proxy for freedom. Whereas music subcultures in the West have faded in the past decades, true rebellion for the members of District Unknown comes in the form of metal, and they have no knowledge of the business imperatives driving the genre overseas. To see District Unknown in action is to witness a kind of alternate history of rock and metal: uncoopted by MTV, uncommercialised, forbidden by the authorities, driven underground and even dissociated from teen rebellion. The band members associate their subculture with independence and autonomy. Watching the film abroad, we can’t help but see the iconography they cobble together as startlingly anachronistic. This is not adolescent waywardness extended into adulthood, however; it is repressed expression isolated from its musical provenance.

As District Unknown’s band members gradually defect to the West – via visas, marriages and study arrangements – we realise that there will probably never be a truly locally inflected Afghan strain of metal. Perhaps Qais, Qasem, Pedram, Lemar and Yousef really are martyrs of the genre. Or perhaps they are just young people seeking small moments of happiness and self-expression in an uncertain, war-torn world.

Endnotes

| 1 | Travis Beard, quoted in Rob Hughes, ‘Rock in a Hard Place: Why Are Iran and Afghanistan Jailing Metal Bands?’, Louder, 17 May 2016, <https://www.loudersound.com/features/rock-in-a-hard-place-why-are-iran-and-afghanistan-jailing-metal-bands>, accessed 14 October 2018. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See, for example, Ron Synovitz, ‘Rock Bands Playing “Stealth” Festival in Kabul, Despite Taliban Attacks’, Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty, 16 September 2011, <https://www.rferl.org/a/rock_bands_playing_stealth_festival_in_kabul_despite_taliban_attacks/24329799.html>, accessed 26 October 2018. |

| 3 | Mark Landler & Helene Cooper, ‘Obama Will Speed Pullout from War in Afghanistan’, The New York Times, 22 June 2011, <https://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/23/world/asia/23prexy.html>, accessed 26 October 2018. |

| 4 | Daniel J Gerstle, ‘Amplifiers in Kabul’, Rolling Stone, 7 December 2011, available at <https://archive.is/da8yk>, accessed 14 October 2018. |

| 5 | ‘Afghan Youth Rock Freedom of Expression at Festival’, CBS News, 3 October 2011, <https://www.cbsnews.com/news/afghan-youth-rock-freedom-of-expression-at-festival/>, accessed 14 October 2018. |

| 6 | Tulip Mazumdar, ‘Rocking Kabul: Afghanistan Stages Secretive Rock Event’, BBC News, 4 October 2011, <http://www.bbc.co.uk/newsbeat/article/15151891/rocking-kabul-afghanistan-stages-secretive-rock-event>, accessed 14 October 2018. |

| 7 | Hughes, op. cit. |

| 8 | See Monica Racic, ‘An Afghan Rock Festival’, The New Yorker, 20 September 2011, <https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/an-afghan-rock-festival>, accessed 14 October 2018. |

| 9 | ibid. |