Fedora-wearing detectives ripped from the pages of Raymond Chandler. Supernatural wraiths clad in black overcoats, their existential experiments splintering a city shrouded in shadows. And, at the core of it all, a dark love story. European auteurs Luis Buñuel and Andrei Tarkovsky – whose unsettling imagery, suggests Alex Proyas, served as inspiration for his Dark City (1998) – would certainly be pleased.

With the tragedy of Brandon Lee’s accidental death on the set of Proyas’ The Crow (1994)[1]See Robert W Welkos, ‘Bruce Lee’s Son, Brandon, Killed in Movie Accident’, Los Angeles Times, 1 April 1993, <http://articles.latimes.com/1993-04-01/news/mn-17681_1_actor-brandon-lee>, accessed 5 November 2017. still but a recent memory, this twisted, genre-redefining tale was certainly a tough sell. But, twenty years on, Dark City has built a reputation among a horde of cult fans as a fascinatingly elusive, strange noir puzzle. Enveloped in skin-crawling, bile-green hues, the film is a whirligig of transmutable buildings – miniatures designed by Patrick Tatopoulos, but shot as though enormous and oppressive in scope – creating an omnipresent sense of the cityscape closing in on itself. For its detective lead, the Humphrey Bogart–like Frank Bumstead (William Hurt), there is no respite, his days spent investigating a series of murders committed throughout the city. Nor is there escape for the man he is pursuing, John Murdoch (Rufus Sewell), who has seemingly lost his memory; the stakes are ratcheted up as he faces the very real possibility that he may be the serial killer responsible for the crimes.

Dark City is steeped in a melange of artistic and literary influences – Tarkovsky, Buñuel, pulp sci-fi novels, George Orwell’s dystopian classic Nineteen Eighty-Four – with the writer/director having positioned his film on the obscure peripheries of cinema:

Philip K Dick’s in there somewhere, too, and the most bizarre stuff went into the mixing pot […] My own dreams at the time found their way into the story. A lot of my other influences emerged – specifically, a lot of literary science fiction […] I think that’s what gave it the bizarre quality it has.

But it wasn’t until after The Crow’s box-office success – the only cache worth a damn in cynical Hollywood, Proyas laments – that his ‘bizarre’ sci-fi would see the light of day. A Gothic action-romance based on James O’Barr’s tragic, partly autobiographical comics of the same name, The Crow is imbued with the melancholy rage of its protagonist, Eric Draven (played by Lee), rising from the grave to avenge his and his fiancée’s murders.

Proyas recalls that developing Dark City’s screenplay was the first critical hurdle:

Beyond that initial brainstorming process and writing the first few drafts, it went through – God help me – studio development […] Some of which was to the detriment of the story, but some of it [was] quite good, in that it forced me to take the narrative into a more lineal direction – in fact, a lot more lineal and cohesive for a mainstream audience.

Alongside co-writers Lem Dobbs and genre specialist David S Goyer, Proyas then shaped the labyrinthine story into something with a more conventional structure. ‘It went through many studios,’ says Proyas.

Initially, Touchstone (I think it was), which is an arm of Disney. Then, it went through Fox. Then, it went to New Line – and I finally got to make it with New Line. But the initial meetings about the script at Disney were quite bizarre: walking into a building in Hollywood that has the seven dwarfs carved out of stone on the facade and talking about the early drafts of Dark City was quite a peculiar experience.

In Dark City’s first scene, John awakens in a bathtub, water murky from the blood of a naked sex worker lying dead in his dank, dark hotel room. Like his character, Sewell had to piece together his ‘identity’ from scratch – no classical British acting techniques could have prepared him for the challenge of building up his character on his own. In a masterful stroke of directorial intervention, Proyas deliberately hid elements of John’s backstory from the actor, to make the character’s discoveries about his past all the more heart-rending. John, we quickly realise, is awash with confusion – racked with suspicion, fear and guilt as a result of the demons that may be hiding within him. He’s wary of love. Only flashes of an idyllic beach vacation in the company of his wife, Emma (Jennifer Connelly), suggest the possibility of rebirth. The two leads’ dynamic is only intensified by Proyas’ methods, the director purposefully giving Connelly the backstory of the couple’s relationship that Sewell was denied. As John and Emma trawl through the details of the murder conspiracy and their marital history, the seeming impossibility that they’ll ever rekindle their love imbues Dark City with an emotional core: a romantic layer beneath the dark science fiction.

As the film’s series of nights gradually make way for the daylight of the final sequences, we learn more about John and Emma’s relationship. Suspecting John of being the serial killer, Bumstead prods Emma to divulge more of what she knows about her husband, dissecting their marriage to ascertain whether or not John is criminally culpable. These scenes, informed by Connelly’s background knowledge, are compelling – the cut and thrust of the detective’s probing and the slow, guarded reveal of John’s identity through the lens of his wife further uncover the pain of what drove the couple apart.

Dark City excites, tantalises and perplexes in equal measure. Peel back the surreal imagery and gallery of weird characters, and the film strikes a surprisingly resonant emotional chord … much like we are, John is scratching through the shadows to uncover who he is.

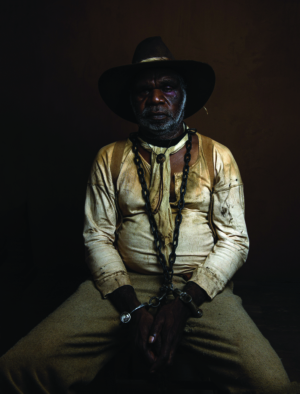

But John’s existential journey – his quest to piece together the shards of his broken life – is hindered further by the presence of eerie figures strangling the city with a supernatural grip. With pallid skin and sunken eyes, bald heads, black trench coats and hats, Dark City’s chilling, otherworldly ‘Strangers’ are noir villains by way of FW Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922): creatures of the night, dwelling in a subterranean lair redolent of German expressionism, drawn to the complexities of humanity though bereft of a human soul. On the stroke of midnight, they transform the cityscape using their telekinetic ability to ‘tune’, bending time and structures, and implanting new memories and identities among the populace. Each Stranger has a call sign – Mr Hand (Richard O’Brien), Mr Book (Ian Richardson), Mr Wall (Bruce Spence); a quirky twist reminiscent of Reservoir Dogs (Quentin Tarantino, 1992) – and their mission is to understand our species. Is it our memories, our cars, our houses and worldly possessions that shape us? What would we mere mortals be without our perceptions shaping our existences, when all of those are stripped away?

The final piece of Dark City’s affecting ensemble is the tortured man under the Strangers’ dangerous thrall who nevertheless helps John unlock the mysteries of the city and regain his life. Proyas brings up a nowadays little-known autobiographical account originally written in 1903, Memoirs of My Nervous Illness by Daniel Paul Schreber. ‘I remember reading that at the time, and being inspired by this bizarre, actually insane mind,’ he recalls. ‘Schreber was a very famous psychoanalytical case in Germany, the sufferer of this psychosis.’[2]Today, this would be known as paranoid schizophrenia. It was this historical figure who provided the basis for the film’s nebbish Dr Schreber. The role was played by Kiefer Sutherland, ‘who very much wanted to embrace a character-actor approach and distance himself from the leading-man or movie-star phase of his career’, recounts Proyas, adding that they had ‘spoke[n] about Peter Lorre in The Maltese Falcon [John Huston, 1941]’ as a reference.

Dark City excites, tantalises and perplexes in equal measure. Peel back the surreal imagery and gallery of weird characters, and the film strikes a surprisingly resonant emotional chord. In continually reshaping the city and interfering in its inhabitants’ lives, the Strangers remain tragically doomed to never comprehend the soul or learn about our common nature. And, much like we are, John is scratching through the shadows to uncover who he is. Ultimately, Dark City operates outside traditional genre conventions – and that’s entirely intentional. Proyas admits he isn’t one to embrace the superficial, thimble-deep Hollywood machine. That’s what makes Dark City special: its path to the big screen was as twisted and bizarre as the work is itself, the film leaving us with more questions than answers regarding what makes us human. To discover more, we dip back into the darkness, searching for answers to bring to light.

Endnotes

| 1 | See Robert W Welkos, ‘Bruce Lee’s Son, Brandon, Killed in Movie Accident’, Los Angeles Times, 1 April 1993, <http://articles.latimes.com/1993-04-01/news/mn-17681_1_actor-brandon-lee>, accessed 5 November 2017. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Today, this would be known as paranoid schizophrenia. |