‘The boats have not stopped,’ wrote The Guardian journalist Ben Doherty of Australia’s controversial asylum-seeker policies back in 2014.

As the world urges closer cooperation on the issue of mass and irregular migrations, Australia grows ever more isolationist. Moving the problem over the horizon is not the same as addressing it.[1]Ben Doherty, ‘“Stopping the Boats” a Fiction as Australia Grows Ever More Isolationist on Asylum’, The Guardian, 31 December 2014, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2014/dec/31/stopping-the-boats-a-fiction-as-australia-grows-ever-more-isolationist-on-asylum>, accessed 30 July 2019.

If we look back on this quote from our increasingly disillusioned 2019 standpoint, Doherty’s reflections feel almost too small-scale. We now know that the Australian politicians who instituted the legislation collected under the slogan ‘stop the boats’[2]For more information on the federal government’s Operation Sovereign Borders policy, see <https://osb.homeaffairs.gov.au>, accessed 30 July 2019. never had any intention of addressing any problem other than voter discontent at who was crossing our borders and the colour of their skin.

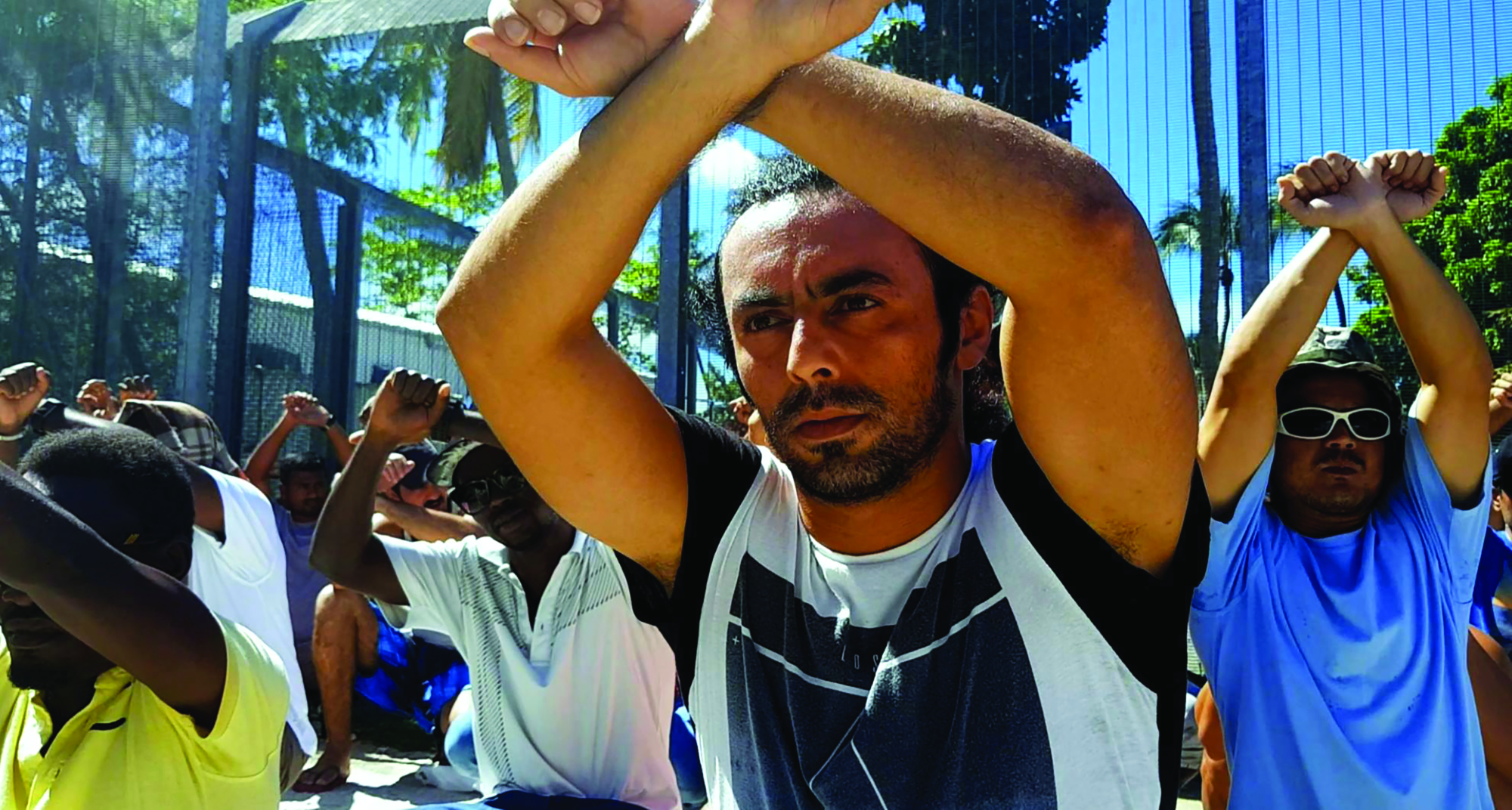

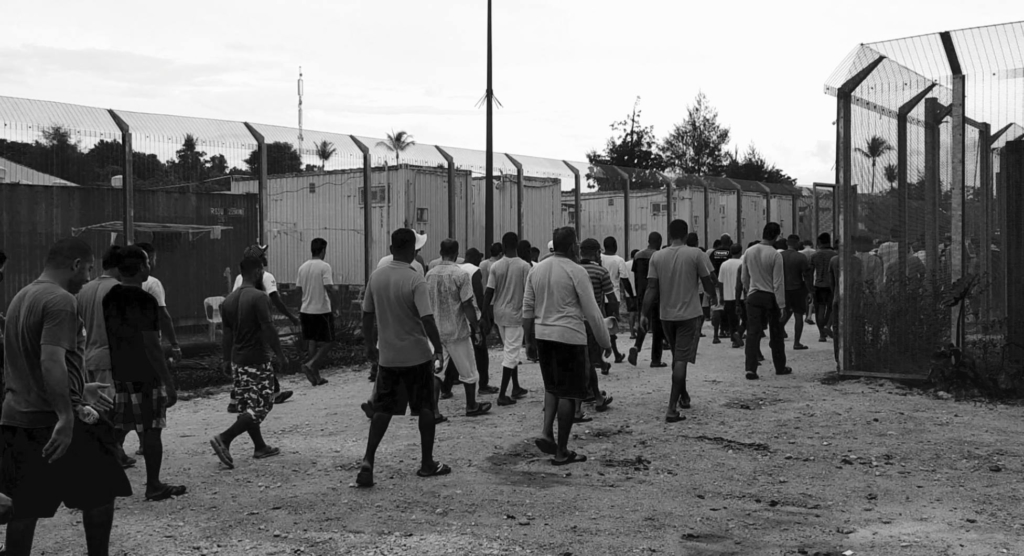

Doherty, who continues to cover Australia’s draconian refugee policies at The Guardian, features prominently in a series of talking-head interviews woven through Stop the Boats, Simon V Kurian’s 2018 documentary about Australia’s deteriorating contributions to the global refugee crisis and the impact of that infamous three-word phrase. Doherty is one of several local voices who contextualise the intense, at times shocking footage that was smuggled on USB drives out of Australia’s offshore detention centres on the islands of Nauru and Manus for use in Kurian’s film.

Stop the Boats is certainly aiming for shock value – and for controversy. Its title alone would incite a buzz among various sectors of the political spectrum, from those who revere Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s bizarre ‘I Stopped These’ boat-shaped trophy,[3]See ‘“I Stopped These”: PM’s Boat Trophy Gains International Notoriety’, SBS News, 19 September 2018, <https://www.sbs.com.au/news/i-stopped-these-pm-s-boat-trophy-gains-international-notoriety>, accessed 30 July 2019. to former and current refugees (and the advocates who seek to help them) who consider the slogan an emblem of fear and cruelty; reportedly, this title was even controversial during Kurian’s research for and filming of the project.[4]Philippa Hawker, ‘Giving a Voice to Those Most Closely Affected by Offshore Detention’, The Australian, 8 May 2019, <https://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/film/giving-a-voice-to-those-most-closely-affected-by-offshore-detention/news-story/f2f58c359ad27b7408d102de71164337>, accessed 30 July 2019. But the filmmaker is adamant that Australians should not forget the rhetoric anytime soon: ‘These are the three words that we need to keep reminding ourselves of, for a very, very long time,’ he told The Australian’s Philippa Hawker.[5]Simon V Kurian, quoted in Hawker, ibid.

And so Kurian has sought to look behind the rhetoric, to the people whose lives have been most cruelly affected by Australia’s propensity for catchphrase politics – settled refugees who have been through Australia’s controversial detention system, and the asylum seekers and refugees still stuck in the centres on Manus and Nauru – as well as the advocates who are fighting for a more compassionate approach. At the centre of Stop the Boats, appearing on footage smuggled from the camps, is Kurdish-Iranian journalist, poet and author Behrouz Boochani, who, this year, won Australia’s richest literary accolade, the Victorian Prize for Literature, for his book No Friend but the Mountains: Writings from Manus Prison. Boochani is no stranger to the public eye in his role as an outspoken advocate for the detainees on Manus and Nauru, and cuts a striking figure on camera. Tall and lithe, with curtains of dark hair framing his sombre face, he is frequently shown in Kurian’s film smoking while on a plastic chair in a quiet corner of the prison, considering the lush tropical landscape beyond the camp’s wire fences. ‘The ocean, the jungle … that is the freedom there, I think,’ Boochani tells the camera.

Those who are used to hearing Boochani speak about his experiences on Manus may be more acutely affected by the footage and voiceovers of children in the Nauru camp. Although Australia states with dubious pride that it has now resettled all children who were once detained offshore,[6]See Helen Davidson, ‘Last Four Refugee Children Leave Nauru for Resettlement in US’, The Guardian, 28 February 2019, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/feb/28/last-four-refugee-children-leave-nauru-for-resettlement-in-us>, accessed 30 July 2019. during Kurian’s filming period, a large number of refugee children were still imprisoned on Nauru – and their stories are the most confronting in the documentary. Dr Munjed Al Muderis, a settled Iraqi refugee who now works as one of Australia’s foremost orthopaedic surgeons, reminisces to-camera about being held in the Curtin Immigration Reception and Processing Centre in the Kimberley, Western Australia. ‘There were over 100 children among us,’ he says. ‘A lot of them were unaccompanied minors. They were incarcerated in the same compounds as everybody else, and these children could have been exposed to all sorts of violations.’

Al Muderis speaks for Kurian – and, presumably, for many in the audience – when he says, ‘I can’t believe and I can’t understand how anyone could incarcerate a child.’ As his voiceover plays, footage of federal police officers screening asylum seekers detained on a shipping dock widens to reveal children playing in the shallows below, still in their clothes, as the adults prepare to board waiting buses. A former medical officer from Christmas Island and Nauru, Dr Ai-lene Chan – who describes Nauru on camera as ‘absolutely the most harsh environment’ – recalls having met most of the children detained there to attend to their self-harm wounds: ‘They would be brought to me to sew up a cut on their arm.’ She explains that, especially for the ‘older children’, there would be ‘a lot of self-harming behaviour’.

But the horrors of Nauru for a child are most hauntingly expressed in Stop the Boats by the children themselves, like the voiceover from Sania, a girl who was detained on Nauru for at least four years from the age of fifteen. Shaky, secret mobile footage tours the bleak layout of the Nauru complex – where detainees ‘don’t have doors’, and ‘it’s all made of plastic and no safety’, with ‘the mould, which make you sick’ – and Sania tells the story of her arrival there:

By plane, I came to Nauru, and it was so hot, extremely hot. And then they took us to our tent. They say, ‘This is where you gonna be staying. How long, we don’t know. But this is where you gonna stay.’

Against the backdrop of despair and discomfort produced by the story that Stop the Boats is telling, there’s the stronger sense that, regardless of what the film exposes, precious little broader change will come from its revelations.

It’s this uncertainty, coupled with the sheer lack of activity on Nauru’s tropical ‘hell’, that has driven a vast majority of the children in custody there to develop severe and ongoing psychological issues. On top of self-harm, Chan identifies that some detainees have had suicidal ideation and adds:

The children in detention are also faced with fairly extreme deprivation, and so they would spend their days not doing anything. I would often see children playing with stones or playing with guards.

Sania’s voiceover then tells us, with a tone of stunning defeat, ‘It feels so bad because we don’t have country. It’s like we have nothing; we have no places to live. So I really want to know: where do we belong?’

For many viewers likely to actually seek out Stop the Boats, these accounts of life on Manus and Nauru from long-suffering detainees will be unpleasant to encounter, though not entirely shocking. Aside from his renowned book, Boochani, who has been on Manus for six years, has been widely published both locally and internationally on the subject of Australia’s border policies; he even presented a talk on the subject, prerecorded in Port Moresby, for TEDxSydney earlier this year.[7]See Emma Brancatisano, ‘“We Exist and We Are Suffering”: The TedX Speaker Who Couldn’t Make It to the Stage’, 10 Daily, 24 May 2019, <https://10daily.com.au/news/australia/a190524ouasj/we-exist-and-we-are-suffering-the-tedx-speaker-who-couldnt-make-it-to-the-stage-20190524>, accessed 30 July 2019. And the distinctly horrifying details of life on Manus and Nauru – especially for the children detained there – have managed to make their way to the media, despite the Australian Government’s best efforts to keep them under wraps. In 2016, The Guardian released its ‘Nauru files’, a cache of over 2000 leaked reports that revealed the distressing abuse of prisoners held offshore in Australian complexes, and its focus was primarily on the children imprisoned in conditions described as ‘routine dysfunction and cruelty’.[8]See Paul Farrell, Nick Evershed & Helen Davidson, ‘The Nauru Files: Cache of 2,000 Leaked Reports Reveal Scale of Abuse of Children in Australian Offshore Detention’, The Guardian, 10 August 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/aug/10/the-nauru-files-2000-leaked-reports-reveal-scale-of-abuse-of-children-in-australian-offshore-detention>, accessed 30 July 2019.

There are myriad other disgraces exposed in Stop the Boats, which may be news even to audiences well versed in Australia’s border policies. Much is made by Kurian and his interview subjects of the ‘stripping of identity’ that happens in camps both on- and offshore – where detainees are referred to by guards and other authorities simply by numbers associated with the boats on which they arrived. The government has vigorously denied this practice occurs inside the camps – especially after reports published by New Matilda claimed that children imprisoned on Nauru were beginning to identify more with their boat identification numbers than with their given names[9]Max Chalmers, ‘Detention on Nauru: Children Now Identify More with Boat Number than Names, Says Former Worker’, New Matilda, 29 June 2015, <https://newmatilda.com/2015/06/29/detention-nauru-children-now-identify-more-boat-number-names-says-former-worker/>, accessed

30 July 2019. – yet both detainees and former detention-centre staff speaking on Stop the Boats are adamant that it has.

But, against the backdrop of despair and discomfort produced by the story that Stop the Boats is telling, there’s the stronger sense that, regardless of what the film exposes, precious little broader change will come from its revelations. Kurian’s film, which premiered independently in 2018, arrived two years after the minor ripples caused by another, arguably more prominent documentary on Australia’s asylum-seeker processes: Eva Orner’s Chasing Asylum (2016). That film, which has been called ‘unmissable’ and ‘a portrait of hell’,[10]Chitra Ramaswamy, ‘Chasing Asylum: Inside Australia’s Detention Camps Review – a Portrait of Hell’, The Guardian, 2 November 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2016/nov/01/chasing-asylum-inside-australias-detention-camps-review-a-portrait-of-hell>, accessed

30 July 2019. toured Australian festivals and had a limited theatrical release before appearing on small screens across Europe and Asia – and yet, in 2019, it feels dated in light of how little Australia’s border policies have changed in the intervening period. Now, as Stop the Boats begins to screen across the country and around the world (it was snapped up in an overseas distribution deal late last year[11]Stewart Clarke, ‘Asylum Seeker Documentary Stop the Boats Gets International Distribution Deal’, Variety, 13 October 2018, <https://variety.com/2018/tv/global/stop-the-boats-asylum-seeker-documentary-gets-international-distribution-1202979463/>, accessed 30 July 2019.), telling the same story with similar urgency, it feels somewhat like the message is bouncing off an immovable brick wall.

There is nonetheless some significant new relevance to Stop the Boats, owing to the parallels between Australia’s detention regime and the US’s recently implemented border policy, which appears to be patterned on Australia’s own ‘deterrent’ blueprint.[12]See, for example, Max Fisher & Amanda Taub, ‘Trump’s Immigration Approach Isn’t New: Europe and Australia Went First’, The New York Times, 18 July 2019, <https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/18/world/immigration-trump.html>; and Peter Mitchell, ‘Aust Migration Policy Wins Fans in US, UK’, The Canberra Times, 27 June 2019, <https://www.canberratimes.com.au/story/6244609/aust-migration-policy-wins-fans-in-us-uk/>, both accessed 5 August 2019. So perhaps there is a lesson offered to overseas – particularly American – viewers who are at the starting point of a dark path that Australia has been winding along for over a decade.

With a work like Stop the Boats, the creator, the participants and the viewers who front up to watch it all hope there will be some change effected by the truths the film exposes. The problem with Kurian’s film, however, is that it feels long past the time when simply exposing the multitude of injustices occurring in Australia’s offshore camps could have elicited any kind of robust positive outcome. The die has been cast, and the country is well entrenched in its muddy deeds on Manus and Nauru, about which most Australians are aware and simply choose to look away from. With little to contribute beyond what we already know about the camps and their conditions – especially as stories from refugees resettled in the US begin to leak out – the audience of the film seems limited to those who feel connected enough to the issue to already know a good deal about its content. At this stage of the campaign for refugee rights in Australia, when so many facts about our human-rights violations are readily available to us and yet we remain apathetic, who is likely to view Kurian’s film beyond those who followed social-justice advocate Julian Burnside’s federal election campaign this year, perhaps, or who bought a copy of Boochani’s No Friend but the Mountains? No matter how well presented, how affecting, Kurian’s story is, he’s preaching to the converted.

Endnotes

| 1 | Ben Doherty, ‘“Stopping the Boats” a Fiction as Australia Grows Ever More Isolationist on Asylum’, The Guardian, 31 December 2014, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2014/dec/31/stopping-the-boats-a-fiction-as-australia-grows-ever-more-isolationist-on-asylum>, accessed 30 July 2019. |

|---|---|

| 2 | For more information on the federal government’s Operation Sovereign Borders policy, see <https://osb.homeaffairs.gov.au>, accessed 30 July 2019. |

| 3 | See ‘“I Stopped These”: PM’s Boat Trophy Gains International Notoriety’, SBS News, 19 September 2018, <https://www.sbs.com.au/news/i-stopped-these-pm-s-boat-trophy-gains-international-notoriety>, accessed 30 July 2019. |

| 4 | Philippa Hawker, ‘Giving a Voice to Those Most Closely Affected by Offshore Detention’, The Australian, 8 May 2019, <https://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/film/giving-a-voice-to-those-most-closely-affected-by-offshore-detention/news-story/f2f58c359ad27b7408d102de71164337>, accessed 30 July 2019. |

| 5 | Simon V Kurian, quoted in Hawker, ibid. |

| 6 | See Helen Davidson, ‘Last Four Refugee Children Leave Nauru for Resettlement in US’, The Guardian, 28 February 2019, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/feb/28/last-four-refugee-children-leave-nauru-for-resettlement-in-us>, accessed 30 July 2019. |

| 7 | See Emma Brancatisano, ‘“We Exist and We Are Suffering”: The TedX Speaker Who Couldn’t Make It to the Stage’, 10 Daily, 24 May 2019, <https://10daily.com.au/news/australia/a190524ouasj/we-exist-and-we-are-suffering-the-tedx-speaker-who-couldnt-make-it-to-the-stage-20190524>, accessed 30 July 2019. |

| 8 | See Paul Farrell, Nick Evershed & Helen Davidson, ‘The Nauru Files: Cache of 2,000 Leaked Reports Reveal Scale of Abuse of Children in Australian Offshore Detention’, The Guardian, 10 August 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/aug/10/the-nauru-files-2000-leaked-reports-reveal-scale-of-abuse-of-children-in-australian-offshore-detention>, accessed 30 July 2019. |

| 9 | Max Chalmers, ‘Detention on Nauru: Children Now Identify More with Boat Number than Names, Says Former Worker’, New Matilda, 29 June 2015, <https://newmatilda.com/2015/06/29/detention-nauru-children-now-identify-more-boat-number-names-says-former-worker/>, accessed 30 July 2019. |

| 10 | Chitra Ramaswamy, ‘Chasing Asylum: Inside Australia’s Detention Camps Review – a Portrait of Hell’, The Guardian, 2 November 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2016/nov/01/chasing-asylum-inside-australias-detention-camps-review-a-portrait-of-hell>, accessed 30 July 2019. |

| 11 | Stewart Clarke, ‘Asylum Seeker Documentary Stop the Boats Gets International Distribution Deal’, Variety, 13 October 2018, <https://variety.com/2018/tv/global/stop-the-boats-asylum-seeker-documentary-gets-international-distribution-1202979463/>, accessed 30 July 2019. |

| 12 | See, for example, Max Fisher & Amanda Taub, ‘Trump’s Immigration Approach Isn’t New: Europe and Australia Went First’, The New York Times, 18 July 2019, <https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/18/world/immigration-trump.html>; and Peter Mitchell, ‘Aust Migration Policy Wins Fans in US, UK’, The Canberra Times, 27 June 2019, <https://www.canberratimes.com.au/story/6244609/aust-migration-policy-wins-fans-in-us-uk/>, both accessed 5 August 2019. |