Did you see the original film version of Nineteen Eighty-Four?

I saw it in 1957 about a year after I first read the book. I was deeply disappointed in it. The book is a distinctively difficult, unfashionable, unmanipulative piece and if it isn’t treated in that way, I don’t see any purpose in doing a film of it.

Are you satisfied with the way it’s been done now? If you were directing it would you have done anything differently?

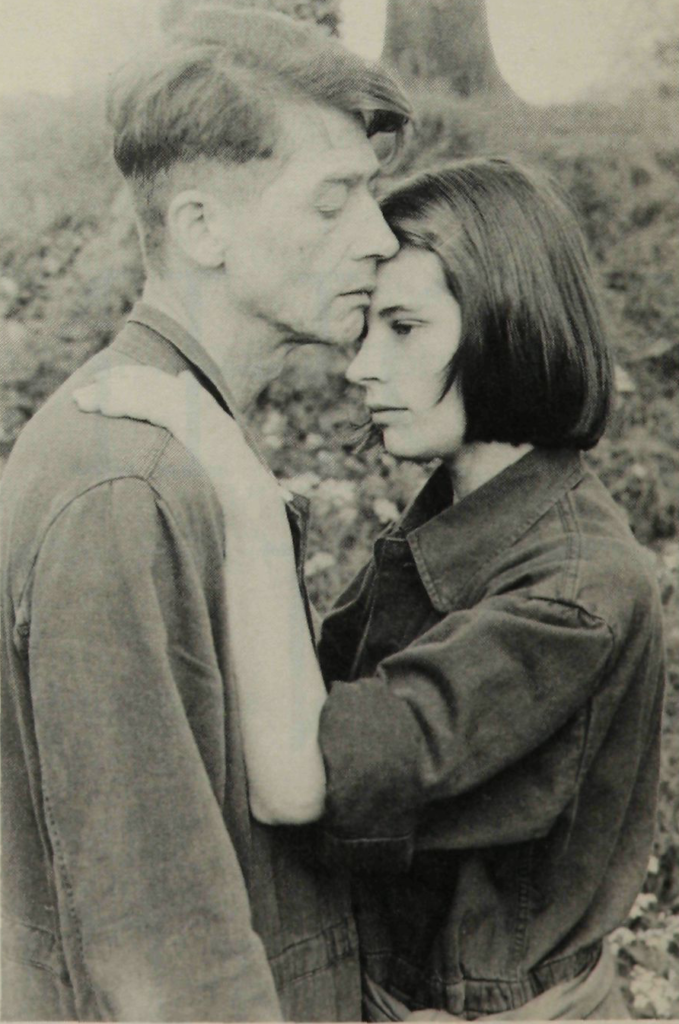

Obviously no two people’s minds are exactly the same in the way they see something. So yes, I think if I had directed it, there are areas that I personally would have accented more but I’m not sure in any way that I’d be right. I would perhaps have played more on the emotional centre of the film, between Julia and Winston. But on the other hand I completely appreciate what Michael Radford was intending and that is that it is happening in Winston’s head, in a sense, and that the love affair should be no more of an incident than anything else which is happening. Indeed to give it more weight, as far as he was concerned, was to verge towards the sentimental which he was trying to avoid at all possible costs. I think he was probably right but it’s very difficult for me to judge the film, it’s only been open a week.

The whole business of making the film was extraordinarily fast. This time last year Simon Perry and Michael Radford were sitting in a wine bar wondering what they were going to do next after Another Time, Another Place and Radford said he’s always wanted to make Nineteen Eighty-Four but he imagined someone had already made it this year. Simon Perry, the producer, said he didn’t think anyone had, at least he hadn’t seen anything about it in the trade papers. So he inquired about where the rights were and discovered Marvin Rosenblum had acquired them some seven days before Sonia Orwell had died. Rosenblum told them that if they could get the money for it and show him a script that he approved of before Christmas, they could go ahead. This didn’t give them a lot of time, so Radford disappeared across to his place in Paris and wrote the script while Simon Perry found the money. Rosenblum was delighted with the script so he came in with the rights.

We started shooting by the end of February or beginning of March and finished shooting on the 22nd of June. Which left very little time to edit it and do the dub which is very difficult in this film. In the Ministry of Truth scenes, for instance, each sound had to be put on. And it’s a very specific kind of sound because the world of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four is somewhat different from anything that we know; it has to be specific and so do the sounds – the Ministry of Truth can’t sound like an old typing pool.

Did you have to fight very hard to get the part of Winston?

No. In November last year, at the Evening Standard Drama Awards, Radford said he wanted to talk to me about something. I said, “if it’s about a film, the answer is YES!” I badly wanted to work with him anyway. I didn’t know until the next day that it was in fact about Nineteen Eighty-Four. I was immensely pleased because I had read the book in 1956 and Winston Smith and the book meant a great deal to me then, as they do now.

It was very easy to identify with Winston Smith. In the fifties, in England, the world was larger for a start. If you were born in the Midlands in England, it seemed one was stuck forever in this grey society of no particular artistic enterprise, which is what I was anxious to pursue. So it was very easy then to identify with Winston but I also think it is very easy for anybody who is in a position of wishing to do something and not having achieved anything. I’m not saying imagery is the same for everybody but when you are beginning your life and you have an eagerness to do something, it seems so utterly impossible to break into that area. That’s the reason he meant an immense amount to me. The book as well, in a different way, has always meant a great deal to me. It did at that age and, for different reasons, has always done so.

What has always interested me is as far as the book is concerned is that it is not, as it is often misconstrued to be a prediction in any sense whatsoever, the title is misleading. It is in fact a perception and I think that perception holds pretty well today as it did then, as it did before he wrote it and certainly as it will do to come. And we should heed Orwell’s perception, a pretty gigantic thing for the human race to do. I don’t have any knowledge of any period in history when human beings have had the sense to say, “well things are not heading in the right direction, we must change the direction”. Obviously that leads us into a fairly pessimistic area of thinking and there is no question that Orwell was a pessimist of a sort, but I believe he had a tremendous love for the human race. He just didn’t see a great deal of hope for it.

Did reading the book and doing the film change your perceptions of the world?

I increased my perceptions of the world. I think every thinking person perceives something of themselves in it. Because what it does by creating that extraordinary but simple imagery and breaking down the complications of life … is to create a somewhat different context in which to look at ourselves objectively, which is what I think Orwell is asking us to do. By putting it into a different era he made a very good canvas for the imagery with which he decided to make the world of Nineteen Eighty-Four. He simplified the whole of life into four basic categories – Big Brother, the Inner Party, the Outer Party and the Proletariat – and to set it in a period which was creeping out of the Christian context of living – which we all live in, whether we’re practising Christians or not.

By using this device Orwell escapes, accidentally, the idea of one side being good and one side being bad. In working in film, you work so closely and so intensely on the thing that it’s very much more than just reading a book. As Richard Burton said, “you know this really is frightening because I’m seriously beginning to believe that what I’m saying is correct.” … It’s very hard to describe, but it’s completely understandable – both sides.

Did you read Orwell’s other works?

I’ve read most of what he has written. He’s one author I can claim that of. Another film I would love to have made which is probably just as heavy as Nineteen Eighty-Four but doesn’t have the political interest is Keep the Aspidistra Flying which I think is a sensational book. I’m too old for it now. Another book which I think would make an amazing film – but it would have to be treated completely differently – is Down and Out in London and Paris. But then I’m not in the business of making books into film. Generally speaking I don’t approve of it. On the other hand if Nineteen Eighty-Four was going to be made, I’m very glad it was Radford who made it. But I think even Radford would generally prefer to make something that was written absolutely for film.

Was the film made from the perspective of 1948 or from today?

It seems to me that Orwell has struck a series of images that are so accurate, so good, a device so cleverly made, that it really is somewhat foolish to take it into another era. He’s created a world which was not 1948 and yet it was. It wasn’t a prediction but it was 1948, but a created world. It would seem almost churlish to say we’ve got to do the same thing only with 19…, it would seem even more confusing. To lift it out of one imagery into another imagery and try to do the same thing. I don’t see how you could do that. Because the piece is written, it is a fact, you’d only be confusing the issue to try to take it further. So why not leave that created world where it stands in history. It doesn’t matter that it’s historical.

Was the opening supposed to resemble a Nazi rally?

It is the world of Orwell’s imagined inheritors. One which is described in ‘oligarchical collectivism’. It has to be checked on, organised, run. And, of course, the irony of the situation is that nothing works in Oceania at all! The lifts, for instance; Winston comes out every morning and stands in front of them, has a short chat with a neighbour, and then without a word they turn and go down the stairs. They know the lift isn’t going to work but they have to be seen to be doing the correct thing!

The parallels are constant but they’re difficult to define and the reason they’re difficult is the reason Orwell chose the starkness of imagery. It’s a reflection of human behaviour, which I think is very lovingly created. The reason for doing that, I think, is that the actuality of life is far too complicated to write about. So what he’s saying is just take the story for what it is worth. Don’t try to say this is representing Nazi Germany, this is representing something else, and so on.

You can look at it on another level. There is nothing in the book which isn’t happening somewhere on this globe at this second. There is nothing there that is not now going on. You can look at it on that level, but that’s not necessarily Orwell’s intention. In order to create his reality he is not going to fake anything, but in the same way that he simplifies the imagery, he also simplifies everything else by putting it into one place. Naturally, it is a novel and therefore it is in the realm of imagination, it is an imaginative work. It is not slavish to any particular happenings.

What do think the future holds for the world of Nineteen Eighty-Four? Will they continue in a constant state of war, will they achieve total control over the mind, or will the system ultimately self-destruct?

It would seem to me unless we change the destiny of mankind that the difference between truth and ‘doublethink’ will be so inexplicable that we will not be able to recognise the difference. In that sense I join Orwell’s pessimism. How ‘doublethink’ can be eradicated I don’t know, we see it everywhere. Every political move is so encrusted with ‘doublethink’. It is already difficult to know whether you are thinking in terms of truth or in ‘doublethink’. As an example, I was watching on television in England the other day somebody who said, “the reason why we didn’t get elected is not because our policies were wrong. Our policies were right, but we didn’t present them the right way.” I think that is a rather alarming statement because what he’s saying is, “if we’d lied correctly, then our policies would have been accepted”. However, he was not just saying that, he was saying it on television! So the people watching were aware of the fact that he was saying, “if we’d lied correctly then you would have believed what we were saying”. It’s like a complicated ‘doublethink’, the whole thing becomes a distortion.

I’d be hard pressed to say exactly what Orwell’s final comment is. It’s the most difficult part of the book and I think it’s the most difficult part of the film. Whether he adheres to the belief that this is definitely the way of the world or whether it is in fact a warning is the most complicated argument of the entire piece.

Was it frightening to do the scene with the rats?

No, my phobia is not rats. But I can tell you in rude detail what I don’t like about rats and that is that when they’re that close to your face and the lights go on, even rats get frightened, so they turn around and fart in your face which is extremely unpleasant when you can’t get that mask off! They are not pleasant to work with.

A lot of people remember the book because of the rats. They think of it as a kind of horror story. Which in a sense it is. But the rats are only an area of Winston’s experience. Radford was very careful not to make that scene one that entered the realm of escapist film making where the whole audience would react as if it were happening to them, not just to Winston. If you confuse that you get into a whole different area of film making.

Room 101 isn’t only the rats. It’s what it (the fear) is to you.

Absolutely.

Do you see Winston as similar to other characters you have played – small people struggling to be themselves?

I suppose there is an undeniable link between people I have played. The first in that line was 10 Rillington Place. Timothy Evans, which was obviously a part I wasn’t going to turn down; it was a fascinating piece and a very interesting character to play. Then a few years later came Quentin Crisp in The Naked Civil Servant, again that’s not a part I was going to turn down, a fantastic script, a wonderful director. Then The Elephant Man came along and what am I supposed to do!

I think I can say I didn’t get any of the characters confused or use anything from one character to try to make it work in another. I like to think I made each one specific. If I were a film maker, everyone would say this link was ‘interesting’ but as an actor people seem to give it to me as a criticism. However, I would like to do a part on a completely different level. I’d like to do a comedy but it’s very difficult to find comedies. When I was at drama school I never did anything but comedy. But good comedies are difficult to find and good comedic directors are an even more rare animal. Good directors are hard to find anyway.

Is that important to you in choosing a role?

Wildly important in films. If you’ve got a good script and you know the man can’t direct, then there’s no point in making it.

Were you able to contribute a lot in this film in the interpretation of Winston?

Yes, we worked a lot on the floor. Michael Radford is film school trained – not that that means he is a product – but the big difference between some one who is trained and someone who comes up through the commercial world is that the commercial world so jealously guards its ideas, basically because they don’t want anything stolen. They tend to be like Alan Parker, who does not let on what is in his mind, he is wonderful to work with but it’s very different. Whereas Michael Radford is very open on the floor. But he is very auteur when it comes to what he puts together.

The others, like Richard Burton, all had their inputs?

Yes, definitely.

Is that usually the case?

No, every film is different, every director is different. Half the skill of making a film is beginning to understand the way in which the director’s mind works as fast as possible, otherwise too much time gets wasted. Or you can find yourself far into the film and thinking, ‘God, if I’d only known him better before, I could have made so much of the earlier part of the film better.’

What was the significance in the opening scene where the crowd hold their hands crossed over their heads?

It’s a symbol which carries strength. It goes with all the slogans which Orwell invented, like “ignorance is strength”. A lot of people say those slogans are ridiculous, that you wouldn’t have people believing a slogan like “ignorance is strength”. But on the other hand Western society is quite happy to accept such slogans as “work equals dignity”. Before the industrial revolution that would have been laughed at! It was only created by the employers as an ideal, and now it’s impossible to get rid of. “Work equals dignity”, what a load of rubbish! It’s surely not the reason human beings are on this earth. Fulfilment may equal dignity, but not work.

One of the things which I think Orwell used as a guideline for the imagery of his world was the Catholic Church. If you think of the Catholic Church operating say, in Naples, and you were going into the inner sanctuary of the Cardinal of Naples (thinking of the Cardinal as the Inner Party) you would find it very different from the humble priest who really believes in the Church and who works among the slums of Naples (with the proletariat). It’s very hard to see how the Catholic Church justifies the way it behaves with the proletariat of Naples, that it actually truly cares for their well-being or their souls. The only way we can justify it is, as I said, that we still live in a Christian context and somehow feel that the clergy must be right. We don’t question it.

If you think about that in the context of Nineteen Eighty-Four, it’s much easier to understand the Inner Party and Big Brother. Even non-Christians will treat the Pope with a certain deference. And yet intellectually, it makes absolutely no sense whatsoever. I think if anyone has a difficulty in understanding Orwell’s imagery, that is the best one to refer them to.

Did you find the last scene emotional, declaring you love Big Brother?

It has to be … to feel love and grief at the same time is something most of us have experienced. You have to decide in your mind exactly what it is you do mean, whether it really is Big Brother you love. Of course, the minute you put it into cinematic imagery you get a greater confusion, you get somewhat of an enigma at the end. Who did he love? Did he love Big Brother or did he love Julia? I personally don’t feel that it matters. That’s where I vary from Orwell.

When he originally wrote it, the ending was 2 + 2 = 5 and he loved Big Brother, but the 5 dropped out (in the printing process) and the first edition came out with 2 + 2 = (blank) and that is the version that has been printed ever since.

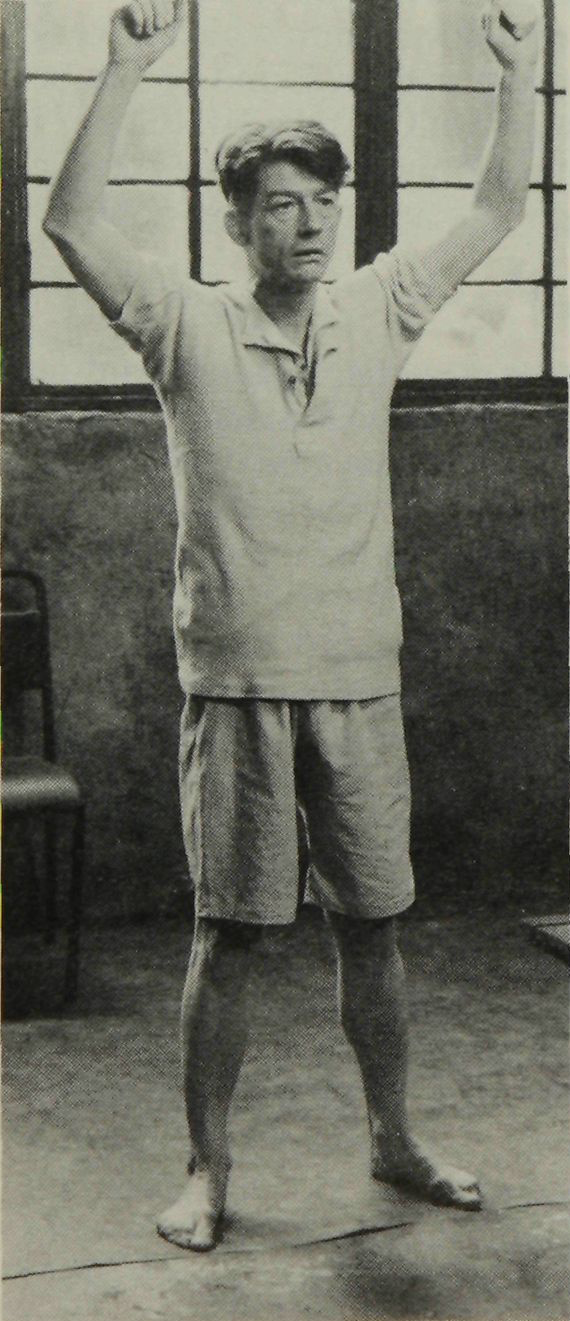

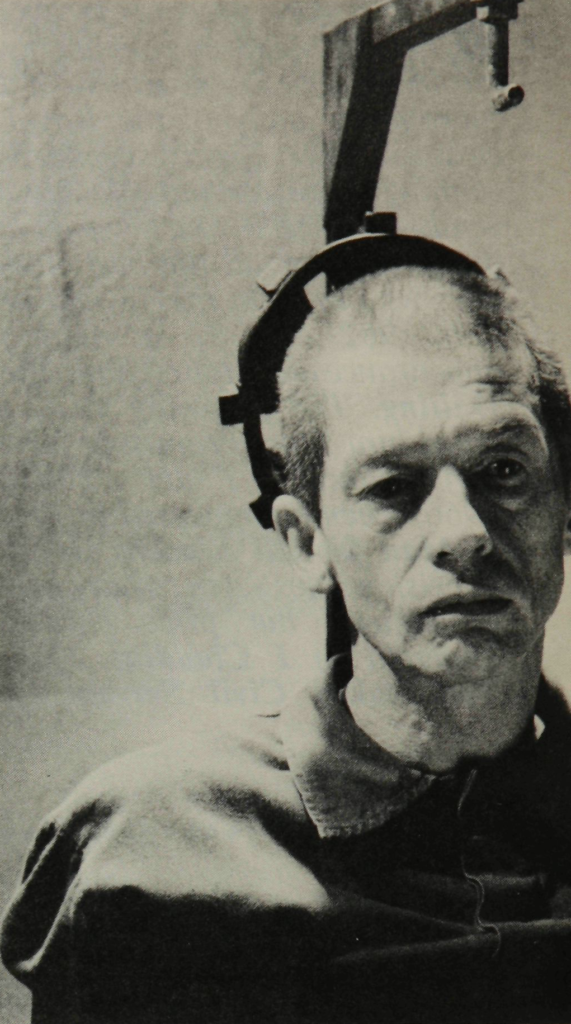

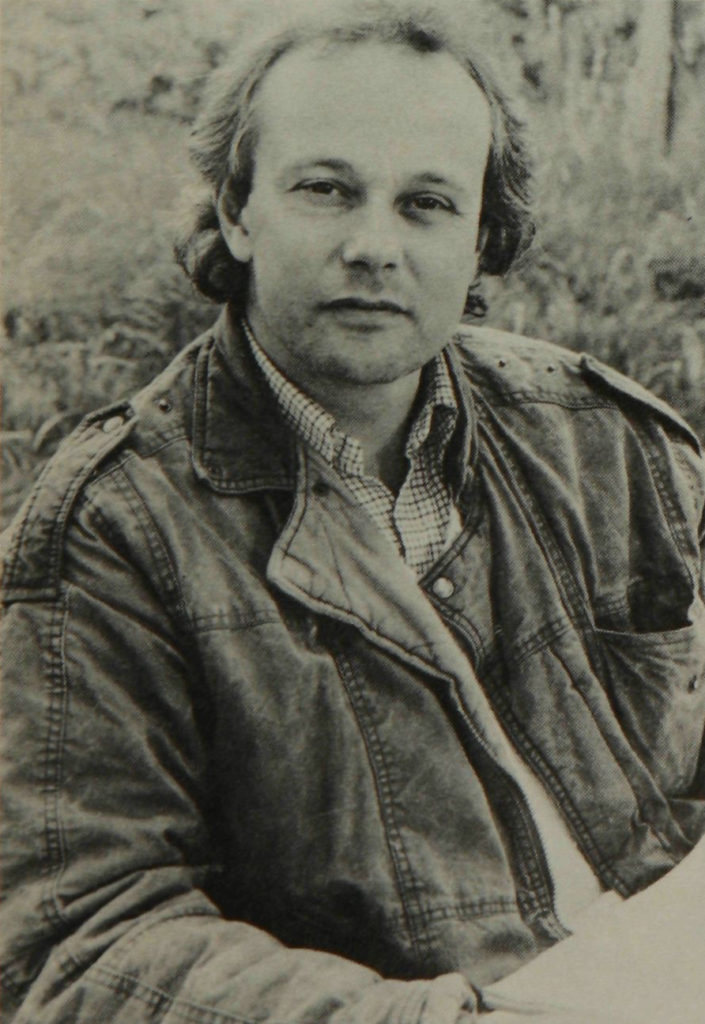

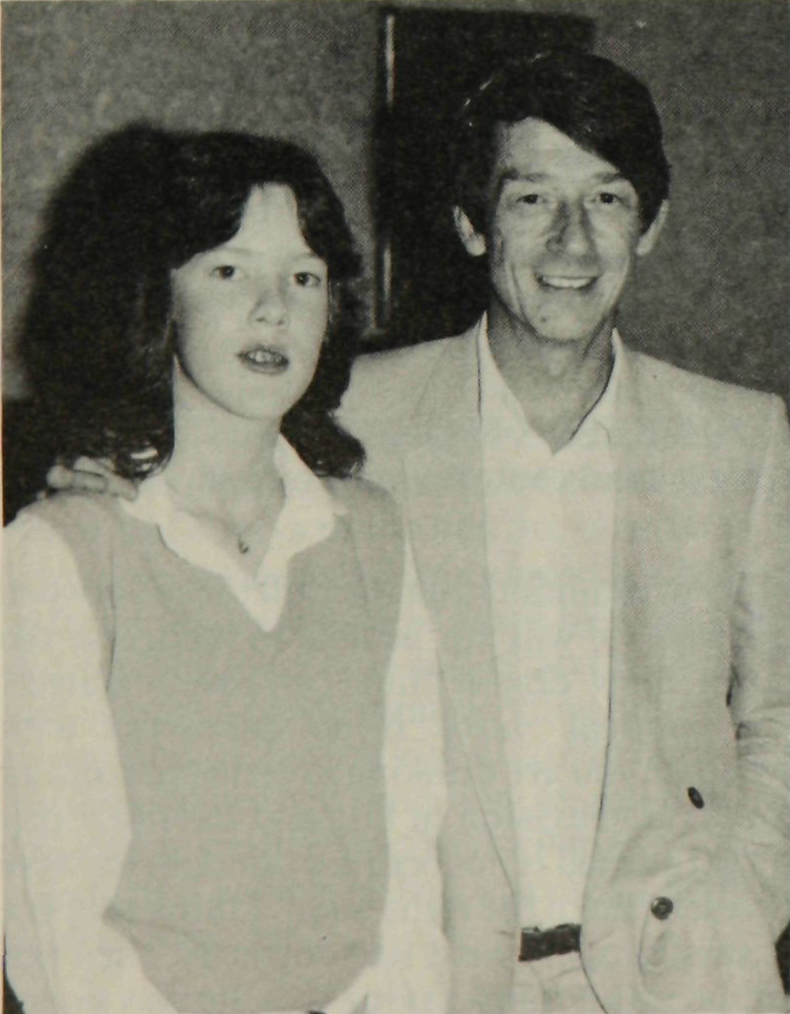

The interview with actor John Hurt was held in his suite in the Windsor Hotel, in surroundings so quietly elegant as to make me feel it was an intrusion to walk through in anything less than the Crown Jewels. This reinforced the image I had of a celebrity concerned with preserving his image – the traditional image of the ‘theatrical’ actor. This, in the case of John Hurt, was quite erroneous.

Here was not the ‘big star’ I expected but a slight, almost fragile man who yet conveyed with great power his thoughts and feelings, not through voice alone, but through the use of his whole body, and who clarified and consolidated my own thoughts before I really realised they were there.

John Hurt was very easy to talk to; he made it easy for me by spicing his comments with drily amusing anecdotes and almost satiric comments. He spoke to me as a person, looking me in the eye and concentrating his whole body on me, and yet when he was talking to the two teachers who were with me or the publicist, I had no feeling of being excluded, merely that they had asked a question and that he was doing them the courtesy of replying directly to them.

With his capacity for making me realise my own ideas, John Hurt forced upon me an awareness of what is really happening; an awareness of how relevant Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four is, and will be. Mr Hurt felt that the book was less of a prediction than a warning – a warning of what will happen to us if we do not stand back and take a look at ourselves and see where we are really heading. He put into words the ideas that to me were still only a feeling of vague unease.

The film was in many ways a surprise. A surprise in how closely it followed the book and how ‘lightly’ they had done the film. I had expected a far more overtly menacing and dramatic film than this, with more of the quiet and controlled violence of the book. Here instead was a film that outwardly would probably be considered to be not nearly as menacing as the book. And yet, after considering it and talking with John Hurt, I have come to consider that perhaps it is more powerful for being less obvious. However, there are still places where the film departs from the book and where it appears that the producers have failed to either mention or make enough of several important scenes in the book. (For example: Syme’s fanaticism, the menacing watchfulness of Parson’s children, the role of the Proles, the Prime Minister’s buck-passing when anything goes wrong.)

The film is, nevertheless, very good and left me with the required feeling of warning. The acting in it is very good and John Hurt’s performance cannot be faulted.

Fiona Kieni