When, exactly, did ‘human rights’ become a dirty phrase? That’s a key question raised by Judy Rymer’s documentary Border Politics (2018), a forceful defence of the rights of people seeking refuge and asylum in Western countries that are turning increasingly hostile.

‘Talking about human rights has become almost unacceptable,’ Border Politics’ narrator, barrister Julian Burnside, tells me. ‘I may be overstating that, but the world’s appetite for respecting human rights seems to have diminished progressively.’

You don’t have to look very hard to find evidence for Burnside’s argument. In her film, Rymer jarringly exposes just how far things have seemingly deteriorated. ‘We must want our fellow human beings to have rights and freedoms which give them dignity,’ former US first lady Eleanor Roosevelt says in archival footage shown in the film, discussing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Rymer then cuts to US President Donald Trump addressing a rally: ‘110,000 refugees in just a single year and we have no idea where they come from, folks,’ he says. ‘This could be the great Trojan Horse.’ Then there’s the moment British Prime Minister Theresa May, ushering in new anti-terrorism legislation, tells an applauding crowd that, ‘if our human-rights laws stop us from doing it, we’ll change the laws so we can do it’.

Despite mostly deploying conventional documentary film language – interviews, archival footage, narration – to make her arguments, Rymer is never unpersuasive. Perhaps the greatest indication that human rights are currently facing sustained attack can be found in the sheer novelty of hearing so many voices defending asylum seekers in the one film. ‘It’s a very unstable period at the moment,’ former Australian Human Rights Commission president Gillian Triggs says at one point, ‘and that is probably why those with an understanding of human rights need to speak up more clearly.’ Through hearing these voices, we are offered a crystal-clear analysis of what’s missing from the broader political discourse. In plugging that gap with Border Politics, Rymer drives home for us that the gap should not exist in the first place.

Perhaps the greatest indication that human rights are currently facing sustained attack can be found in the sheer novelty of hearing so many voices defending asylum seekers in the one film.

A global perspective

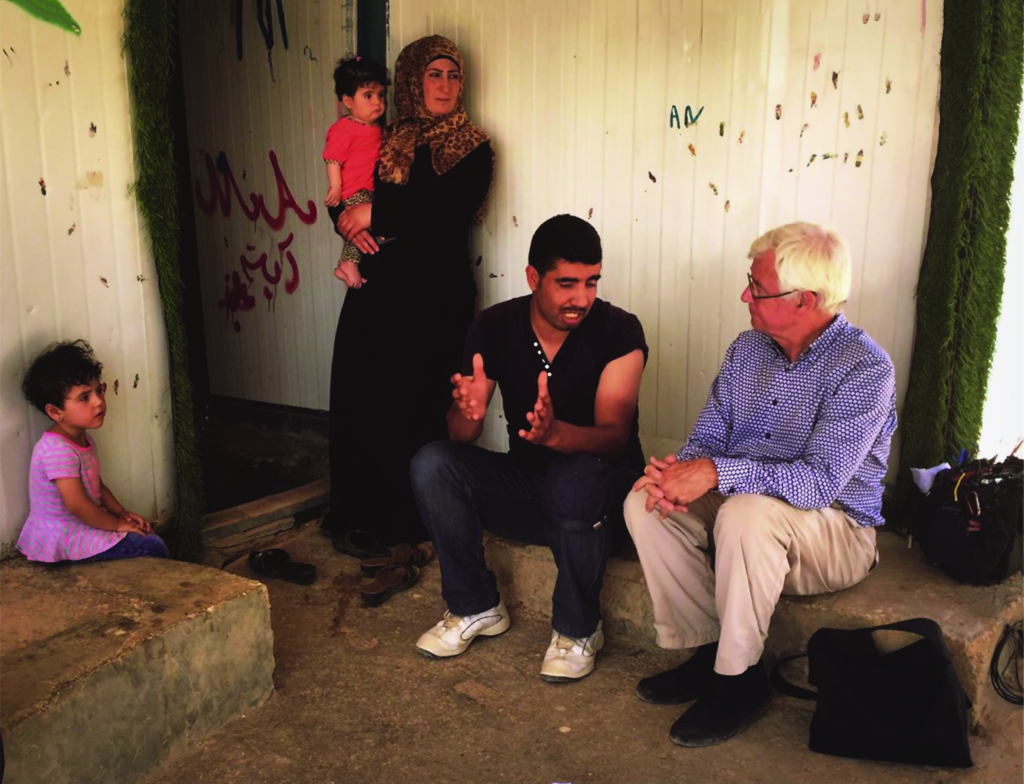

Taking the form of a global tour of borders and monuments, Rymer’s documentary is anchored by Burnside, who interviews various experts at home and abroad. They include Human Rights Watch executive director Kenneth Roth, psychologist and trauma expert Paul Stevenson, and United Nations special adviser Karen AbuZayd. Not quite a journalist but not just a talking head, either, Burnside makes for a curious figure on screen. He is alternately prone to legalistic understatement and outbursts of emotion. ‘Refugees are a group who need to benefit from a little bit of social change,’ he mildly observes at one point, while at another he notes that ‘in many countries, a lot of the politicians are dishonest bastards’.

Rymer tells me that she ‘didn’t want to put words into his mouth’. Rather, the film’s researchers put together notes for each location that Burnside and the crew visited, which he then used as the basis for his commentary. For much of the time that he’s on screen, Burnside speaks directly to the camera. It was a decision that Rymer describes as a ‘craft risk’, albeit one that paid off: ‘It really works to create a direct relationship with the viewer.’

Before finding himself as one of Australia’s leading voices for refugees, Burnside notes in the documentary, he was a ‘typical conservative lawyer’ doing commercial work for the big end of town. But things changed when he volunteered his legal services pro bono in the Tampa[1]See Alex Reilly, ‘Australian Politics Explainer: The MV Tampa and the Transformation of Asylum-seeker Policy’, The Conversation, 27 April 2017, <https://theconversation.com/australian-politics-explainer-the-mv-tampa-and-the-transformation-of-asylum-seeker-policy-74078>, accessed 1 August 2018. case. The experience, he says, was a revelation. ‘I’d never had the slightest interest in politics, and I frankly did not know what we were doing to asylum seekers,’ he tells me. ‘By doing that case, I came across a lot of people who knew a lot about refugee policy, and what I learned really shocked me. Ignorance protected me until 2001.’

Rymer first interviewed Burnside for a documentary she made about the Tampa incident, Punished Not Protected (2004). When she approached him to anchor Border Politics, he initially turned her down. ‘He said that his participation in this area was frowned upon in some sectors, and he didn’t know if it was his place to be making a film,’ she says.

We convinced him by saying that he was consigning us to only hearing from people less informed than him about the law and, at that point, he agreed to participate, which was jolly good for us.

‘You see the wretched little boats in which people try, desperately, to seek safety in Australia, and those boats are often so badly kept that they fall apart in the ocean … What’s our response? Our response is: when people fall at our feet, we kick them in the face.’

Signs of optimism at the local level

If a clear thesis emerges over the course of Border Politics’ grand international tour, it’s that local communities are capable of doing remarkable things when their national governments fail them. From the councils in Scotland resettling Syrian refugees to the citizens of the Greek island Lesbos establishing their own refugee camps, the film’s most hopeful moments come when Rymer shifts focus away from broad political brushstrokes and examines the steps ordinary people are taking to help others. ‘That’s probably true everywhere,’ Rymer notes.

In Australia, we have many groups beavering away trying to help people with Temporary Protection Visas. There are many groups who are basically keeping these people alive in many ways and doing the work of the government, really.

Throughout the film Burnside speaks bracingly of the architecture and design behind the myriad walls he visits, from the ‘Great Wall of Mexico’ on the US border to the remains of the perimeter fence of the now-abandoned Calais refugee camp in France, known as the ‘Jungle’, which was once home to some 10,000 people. The Calais fence contains four layers of razor wire. ‘The fences are here to stop people,’ Burnside notes in the film. ‘The level of the barriers is emblematic of the desperation of the people – a desperation that is recognised by the people who put them up.’

The sheer scale of the physical barriers was ‘very distressing’, he says now, a physical manifestation of the hardening attitudes towards asylum seekers and refugees across the West, including in Australia.

You see the same thing here. You see the wretched little boats in which people try, desperately, to seek safety in Australia, and those boats are often so badly kept that they fall apart in the ocean […] What’s our response? Our response is: when people fall at our feet, we kick them in the face.

A failure to communicate

When you get down to it, the concept of human rights is not complicated. As the seemingly indefatigable Lesbos-based volunteer Efi Latsoudi puts it in Border Politics, ‘For me, it’s very simple: these people need protection, and we stand with them. Human rights cannot be for some.’

Rymer made the documentary partly, she says, because Australia does not have an honest discourse when it comes to asylum seekers and refugees. ‘It’s a failure. I think we should be talking about it, and I think that the storyteller’s duty of care in our country on this matter is lacking, [which] makes me very sad.’ Throughout her career, Rymer has made films about human rights. She’s drawn to stories about individuals, particularly those that offer a way into the bigger picture of politics. ‘I often think an individual story represents a political situation,’ she reflects. ‘It’s terrific to find inspiration in other individuals.’

Monuments and memorials

Alongside the border walls, Border Politics places great emphasis on monuments and memorials. Burnside seems genuinely humbled and reflective at each site he visits, from Paris’ Place de la République to New York’s Statue of Liberty (‘surrounded by myths more than reality’, he observes). Although not strictly memorials, he recalls now that Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty were both profoundly moving sites to visit and reflect on:

When you consider the significance of Ellis Island and all that it promises, and the number of people who entered America through it, you think – well, what a profound irony that the very place that is the source of the building of the USA now stands as a testament to the exact opposite message. The message of the USA now is: outsiders aren’t really welcome, and especially Muslims. I just thought that was interesting.

The sharp change in attitudes, Burnside notes, means that, in the case of the Statue of Liberty, a ‘symbol now stands in contradiction to the current facts’.

Another memorial the film turns its lens on is Canberra’s SIEV X project, a grassroots work created by community groups and schools to commemorate the 353 people who died when a refugee boat capsized in 2001. Burnside stresses that, against the wishes of the government at the time, ‘thousands of unknown ordinary Australians collaborated to put together the monument to the SIEV X and, by doing so, expressed their genuine concern for people seeking asylum’.

Again, the underlying point is clear: when governments fail to lead, the community steps in. But how sustainable is this, really? Border Politics is optimistic, in the sense that it does showcase a variety of experts in several different countries who are very much at work to defend human rights. ‘I think that’s quite hopeful, in a way,’ Rymer says.

There’s a dreadful tide and [… in] the face of horrifying developments in the shift to the right and the building of walls, there are people who are completely committed to developing human rights. That does give you hope.

Elsewhere, though, that hope is beginning to fade. One of Border Politics’ most affecting moments comes towards its end, when, in the middle of an interview, journalist and commentator David Marr takes off his glasses. He rubs his eyes in a candid display of fatigue. ‘There has to be a way of getting to a point where people realise that what was done in these years was needless and cruel,’ he says. ‘But I’ve lost any sense of how we get there. [I] don’t know how we get there.’

According to Rymer, Marr’s brief moment of surrender has an emotional impact because he’s ‘one of the heroes of the subject, in journalistic terms’: ‘I understand where he’s at. It does seem to me that it’s terribly difficult to modify the political purpose in this debate.’

Does Burnside share Marr’s despondency?

‘How do you break through that? You can call [Minister for Home Affairs Peter] Dutton a liar and he ignores it, and no-one hears you say it. I just don’t, really … I do not know.

I’ve tried many different ways of drawing all of this to the attention of other Australians, who, I think, would be shocked if they knew it [was happening]. I fear that what might happen is that, in twenty or thirty years time, the next generation of Australians will look back and think, ‘What on Earth did they think they were doing?’

https://www.rymerchilds.com/borderpolitics

Endnotes

| 1 | See Alex Reilly, ‘Australian Politics Explainer: The MV Tampa and the Transformation of Asylum-seeker Policy’, The Conversation, 27 April 2017, <https://theconversation.com/australian-politics-explainer-the-mv-tampa-and-the-transformation-of-asylum-seeker-policy-74078>, accessed 1 August 2018. |

|---|