‘You have to see it to be it.’ While tennis legend Billie Jean King was speaking about gender equality on the tennis court,[1]King features this quote on the homepage of her website. See <https://www.billiejeanking.com/>, accessed 24 August 2020. the aphorism has broad application, especially concerning on-screen representation. Acknowledging the lack of diversity in the Australian screen over the past few years, as well as the barriers for emerging filmmakers to get a start in the industry, Screen Australia has responded with several targeted initiatives. These partnerships with broadcasters and other organisations have funded projects that bring newer voices to broader audiences. Such initiatives have included the online-focused Skip Ahead, with Google, which supports YouTube content creators who have already collected over 25,000 subscribers;[2]‘Skip Ahead’, Screen Australia website, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/funding-and-support/television-and-online/production/special-initiatives/skip-ahead-vi>, accessed 24 August 2020. Doco 180, with News Corp Australia’s Whimn platform, a fund for three-minute micro docs by women;[3]‘Special Initiative: Doco180’, Screen Australia website <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/funding-and-support/documentary/production/special-initiatives/doco180>, accessed 24 August 2020. and DisRupted, with ABC Children, for filmmakers with disabilities.[4]‘ABC and Screen Australia Unite on DisRupted’, media release, Screen Australia, 31 October 2018, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/sa/media-centre/news/2018/10-31-abc-and-screen-australia-unite-on-disrupted>, accessed 24 August 2020. With the ABC, Screen Australia has also commissioned several series through its Art Bites initiative, providing opportunities for emerging filmmakers to tell stories that reflect their diverse backgrounds, such as journalist Santilla Chingaipe’s Third Culture Kids and trans-rights activist Sam Matthews’ Unboxed. This article looks at recent initiatives directed towards small-screen[5]As viewing habits shift across platforms, the parameters are increasingly blurred, with the range of small screens now incorporating broadcast (or terrestrial) television, including the flagship stations and their range of digital additions; video-on-demand streaming services such as Netflix, Stan and Amazon Prime; and free-to-air digital platforms such as ABC iview and SBS on Demand. LGBTQIA+ stories and storytellers. More specifically, I’ll focus on two recent Screen Australia–funded initiatives: 2018 ABC production Love Bites and Network 10’s Out Here, the latter a trio of half-hour TV documentaries featuring LGBTQIA+ rural stories. In discussing these two initiatives, I will explore different representations of LGBTQIA+ lives and queerness in Australian small-screen documentary.

Although Screen Australia’s landmark 2016 study of diversity on Australian television, Seeing Ourselves: Reflections on Diversity in Australian TV Drama, focuses on drama production, the findings can be extrapolated. The report concludes that, although one in ten Australians identify as LGBTQIA+, only 5 per cent of characters on screen reflect these sexual orientations and gender identities.[6]Screen Australia, Seeing Ourselves: Reflections on Diversity in Australian TV Drama, 2016, p. 17, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/getmedia/157b05b4-255a-47b4-bd8b-9f715555fb44/tv-drama-diversity.pdf>, accessed 24 August 2020. However, the report also acknowledges a shift over time resulting in more on-screen queer characters whose sexuality is ‘incidental’ rather than ‘pivotal.’[7]The report defines ‘incidental’ as sexual identity being ‘everyday and unremarkable’, in comparison with ‘pivotal’, in which it forms the dominant storyline. See ibid., p. 18. In her study of LGBTQIA+ representation of fictional characters on Australian television over the last three decades of the twentieth century, screen researcher Whitney Monaghan writes that work that sits within the respective genres of documentary, current affairs and reality television is ‘notable for its inclusion of diverse sexualities’.[8]Whitney Monaghan, ‘Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Representation on Australian Entertainment Television: 1970–2000’, Media International Australia, vol. 174, no. 1, pp. 49–58, 2019, p. 57. This is because documentary has traditionally facilitated a broader representation of sexualities on screen through its tendency to foreground lesser-told stories and corners of society not often seen through dramatic representation. However, very few studies have looked at Australian LGBTQIA+ or queer documentaries on the small screen.

With the shift away from the commissioning of single documentaries for television, there have been fewer opportunities for risk-taking with subject matter and form. However, online platforms such as ABC iview and SBS on Demand have enabled content that might otherwise be considered too risky to broadcast in terms of its capacity to find audiences. These platforms also allow for works of different lengths that don’t fit neat broadcast slots. One such example is the series Love Bites,commissioned by Screen Australia and the ABC to mark the fortieth anniversary of the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras in 2018.This series of ten episodes of five to eight minutes, each directed by a different filmmaker, is remarkable in that it not only includes diversity across the spectrum of sexuality but also contains a broad range of intersecting identities: lesbian, trans, drag-king, Pakistani, Samoan and Arab-Australian, among others. In the spirit of Mardi Gras, these shorts foreground the body, sexuality and gender through playful performativity. In Ramon Watkins’ Dances, the online world of hook-ups is played out through text messages popping up on screen against the physicality of bodies dancing in various otherwise-empty industrial spaces. Micro narratives of racism, transphobia, secret desire, shame and empowerment are embodied within the movements. The intersectionality of identities and sexuality and slippage across ‘private and public spaces’ evoke what film scholar Jeffrey Geiger refers to as a notable aspect of queer documentary.[9]Jeffrey Geiger, ‘Intimate Media: New Queer Documentary and the Sensory Turn’, Studies in Documentary Film, June 2019, p. 2.

In discussions of LGBTQIA+ representation, it’s also important to tease out some of the definitions of what ‘queer’ means, and what might constitute a queer screen work. Whereas ‘LGBTQIA+’ broadly pertains to sexual orientation and gender identity, ‘queer’ can have multiple interpretations. For film professors Karl Schoonover and Rosalind Galt, ‘queer cinema’ is difficult to define because it is subject to interrogation and shifts across contexts and times; sometimes a film may be interpreted as queer despite the original intended audience not being so. The authors suggest that queer cinema can be defined by either the subject matter, the identity of the directors or that of the viewers. However, they also question who and what is excluded when ‘these logics are imposed as the prerequisite for defining queer cinema’.[10]Karl Schoonover & Rosalind Galt, Queer Cinema in the World, Duke University Press, Durham, NC, 2016, p. 8. Further, Schoonover and Galt note that, beyond the subject matter of queerness, queer cinema can be defined through distorting and subverting conventional filmic languages and ‘warping normative regimes of visuality’.[11]ibid., p. 10.

While many of the shorts in the Love Bites seriesexhibit tropes familiar from queer classics such as Tongues Untied (Marlon Riggs, 1989) and Paris Is Burning (Jennie Livingston, 1990), LGBTQIA+ and queer stories from regional, rural and non-urban parts of Australia are less common. As Deakin University lecturer Paul Venzo has observed, LGBTQIA+ identity has traditionally been associated with the city, meaning that rural narratives seeking to explore it have suffered.[12]See Emma Nobel, ‘Coming Out in Regional Victoria and Overcoming Homophobia and Secrecy for LGBT People’, ABC South West Vic, 3 October 2019, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-10-03/overcoming-secrecy-and-homophobia-in-a-rural-town/11569018>, accessed 24 August 2020. And when these stories are told, they often adhere to ‘bury your gays’, the television trope in which LGBTQIA+ characters are introduced only to meet with unhappy endings, namely death – think Brokeback Mountain (Ang Lee, 2005)and Boys Don’t Cry (Kimberly Peirce, 1999).In discussing the tradition of the queer rural character in literature, researcher Rob Ridinger writes:

An enduring part of LGBT mythology has been the story of the small-town man or woman who claims an identity outside the heterosexual mainstream culture in which they have been immersed from childhood, and is forced by circumstances ranging from expulsion by their biological families to loss of jobs to pack their bags and head for the nearest large urban center where they can become part of a community of people like themselves.[13]Rob Ridinger, ‘Off the Shelf #17: Down Country Roads: LGBT Rural Life and Communities’, Rainbow Round Table Book and Media Reviews,2016, <https://www.glbtrt.ala.org/reviews/off-the-shelf-17-down-country-roads-lgbt-rural-life-and-communities/>, accessed 24 August 2020.

The three stories told in the Out Here trilogy present counter-narratives to both LGBTQIA+ urban stories and the few representations we have of regional and rural life.

Ridinger also claims there is a parallel history of stories of characters who choose to live their lives in rural areas, out and open about their sexuality.[14]ibid. These narratives are generally less visible than their urban counterparts. To make visible some of these stories, in 2019 Screen Australia and Network 10 launched the initiative Out Here to give three emerging filmmakers from rural areas up to A$80,000 to produce a half-hour documentary to be showcased on online platform 10 play. The three projects selected were The Rainbow Passage, Belonging and Alone Out Here.While these documentaries can be considered stylistically conventional, foregrounding LGBTQIA+ lives through films such as these can provide queer interventions into regional and rural representations.

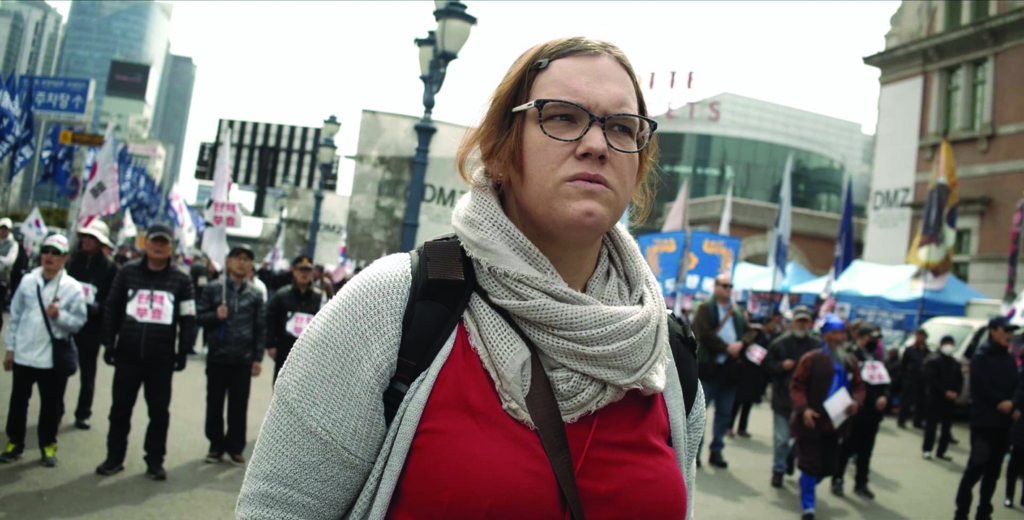

The Rainbow Passage, directed by Cadance Bell (and co-directed by Kelli Jean Drinkwater) follows her and her partner Amanda Sato’s ‘gender affirmation journey’[15]‘Synopsis’, The Rainbow Passage official website, <https://therainbowpassage.com/synopsis/>, accessed 24 August 2020. from the New South Wales town of Bathurst to Seoul and back. Like a queer romantic buddy film, the intimate portrait of the couple as they go through voice surgery counters the oft-told tragic narrative of LGBTQIA+ people in rural areas. Along with their friend Hannah Maher, who lives in the nearby town of Trundle, Bell and Sato navigate their new lives within their communities of friends and family. What comes through in this film is the possibility of consciously building a community through the choices one makes.

While telling a bigger story about community and acceptance, The Rainbow Passage functions less as a singular narrative than as a collection of small vignettes from its subjects’ life together. This serves to make visible their private conversations and everyday moments against the backdrop of what this regional Australian town is arguably known best for, the Bathurst 1000 race. Using the affordances offered by technology and participant access to tell intimate stories, The Rainbow Passage exhibits what critical-studies theorist Michael Renov calls a ‘domestic ethnography’.[16]Michael Renov, The Subject of Documentary, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2004, pp. 216–29. However, with the filmmaker positioned as the subject of the documentary, it leaves me as a viewer wanting more of the reflection and intimacy that come with the autobiographical perspective.

Belonging, directed by Matt Scholten, tells the parallel stories of eighteen-year-old LGBTQIA+ activist Sam Watson and veteran gay-rights campaigner Rodney Croome in the last Australian jurisdiction to legalise homosexuality, their shared home state of Tasmania. Employing the most conventionally televisual style of the three films, Belonging is told as a presenter-led first-person journey following Watson’s experience growing up on the north-west coast of the island. Visiting significant sites of gay activism, he reflects on how Croome’s actions changed both attitudes towards LGBTQIA+ people and laws around homosexuality in Tasmania. Belonging is ultimately a story of how Croome’s activism paved the way for young LGBTQIA+ people today through the perspective of a young person who has both benefited from and been empowered by these actions.

In the third instalment of the trilogy, Alone Out Here, director Luke Cornish shows us another dimension to farming in Australia. Few depictions of rural and regional Australia exist on mainstream television; in the announcement of the 2020 return of a rare exception, Channel Nine’s Farmer Wants a Wife,five straight white men were unveiled as the latest contestants in the dating show. While casting beyond convention might be a challenge for the latter show, it is essential that productions do more to reflect the intersectional composition of communities and identities beyond urban centres. Cornish’s film does just that, bringing to the fore another significant issue affecting rural lives in Australia – climate change – as fourth-generation New South Wales cattle farmer Jon Wright battles both loneliness and environmental catastrophe to transform his farm into a more sustainable operation. Beautifully shot, the quintessential images of the dusty farm capture the iconic imaginary of rural Australia, one that is already familiar from filmic representations. But this film is not about coming out and celebrating the changing attitudes to sexual identity in broader Australia; it is largely about a different kind of coming out – as an environmentally sustainable cattle farmer – as Wright struggles to have his farming practices accepted. Alone Out Here is also undeniably more melancholy than the other two films: the central character is older, so there is less focus on the changing landscape of acceptance of LGBTQIA+ people; and further, being connected to the land in such a tangible way, Wright lacks the mobility of the subjects of The Rainbow Passage and Belonging.

While being gay is a significant part of the parallel storyline in Alone Out Here, the narrative arc centres on his annual bull auction and the primary obstacle presented by the drought. The film begins by introducing the environmental impact of beef, with the audience soon learning – as he talks about the loneliness and depression that came with looking for a partner – that Wright’s commitment to farming has come at a price. The film charts his search for validation and acceptance both in the farm and in his personal life, and ultimately depicts his deep commitment to living honestly – by being open about his sexuality and doing what he can to combat climate change.

The three stories told in the Out Here trilogy present counter-narratives to both LGBTQIA+ urban stories and the few representations we have of regional and rural life. These are essential in making visible lives that exist outside of normative narratives. While they don’t contain the noticeably queer tropes of Love Bites, and could be considered safe through their representation of the non-sexualised body, they do examine the intersecting identities and lived experience of people we don’t often see. Writing about the establishment of Australia’s first regional queer film festival, filmmaker Akkadia Ford describes how the impetus to create it grew out of a desire to challenge the ‘distance, social invisibility and entrenched homophobia [that] is intensified through invisibility within the media and other cultural outlets and through the hegemony of heteronormativity encountered on a daily basis’.[17]Akkadia Ford, ‘Regional & Queer: Refusing to Be Invisible, Creating Queer Space in a Non-queer World’, Cybergeo: European Journal of Geography, 10 February 2017, p. 3, available at <https://journals.openedition.org/cybergeo/27952?lang=en>, accessed 24 August 2020.

While it is encouraging to see more diversity on small screens, these initiatives should also provide more than a one-off shot to produce a film. Instead, they should be pathways for practitioners to continue to tell the kinds of stories that reflect the complexity of identity in all parts of Australia. The fact that the films from Love Bites and Out Here were commissioned specifically for the online portals of broadcasters raises the question of their reach to audiences that may not otherwise encounter these stories. And while these online platforms provide spaces for audiences who feel that Australian broadcast television is not catering to their needs and tastes, relying solely on the internet means that, as Screen Australia puts it, ‘we lose the important integrating effect of free-to-air broadcasting, with its opportunities for shared conversations and insights into unfamiliar communities and experiences’.[18]Screen Australia, Seeing Ourselves, op. cit., p. 24. For, as important as it is for these stories to be told, it is also essential that they find audiences beyond those who go looking for them.

Endnotes

| 1 | King features this quote on the homepage of her website. See <https://www.billiejeanking.com/>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

|---|---|

| 2 | ‘Skip Ahead’, Screen Australia website, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/funding-and-support/television-and-online/production/special-initiatives/skip-ahead-vi>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 3 | ‘Special Initiative: Doco180’, Screen Australia website <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/funding-and-support/documentary/production/special-initiatives/doco180>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 4 | ‘ABC and Screen Australia Unite on DisRupted’, media release, Screen Australia, 31 October 2018, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/sa/media-centre/news/2018/10-31-abc-and-screen-australia-unite-on-disrupted>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 5 | As viewing habits shift across platforms, the parameters are increasingly blurred, with the range of small screens now incorporating broadcast (or terrestrial) television, including the flagship stations and their range of digital additions; video-on-demand streaming services such as Netflix, Stan and Amazon Prime; and free-to-air digital platforms such as ABC iview and SBS on Demand. |

| 6 | Screen Australia, Seeing Ourselves: Reflections on Diversity in Australian TV Drama, 2016, p. 17, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/getmedia/157b05b4-255a-47b4-bd8b-9f715555fb44/tv-drama-diversity.pdf>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 7 | The report defines ‘incidental’ as sexual identity being ‘everyday and unremarkable’, in comparison with ‘pivotal’, in which it forms the dominant storyline. See ibid., p. 18. |

| 8 | Whitney Monaghan, ‘Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Representation on Australian Entertainment Television: 1970–2000’, Media International Australia, vol. 174, no. 1, pp. 49–58, 2019, p. 57. |

| 9 | Jeffrey Geiger, ‘Intimate Media: New Queer Documentary and the Sensory Turn’, Studies in Documentary Film, June 2019, p. 2. |

| 10 | Karl Schoonover & Rosalind Galt, Queer Cinema in the World, Duke University Press, Durham, NC, 2016, p. 8. |

| 11 | ibid., p. 10. |

| 12 | See Emma Nobel, ‘Coming Out in Regional Victoria and Overcoming Homophobia and Secrecy for LGBT People’, ABC South West Vic, 3 October 2019, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-10-03/overcoming-secrecy-and-homophobia-in-a-rural-town/11569018>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 13 | Rob Ridinger, ‘Off the Shelf #17: Down Country Roads: LGBT Rural Life and Communities’, Rainbow Round Table Book and Media Reviews,2016, <https://www.glbtrt.ala.org/reviews/off-the-shelf-17-down-country-roads-lgbt-rural-life-and-communities/>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 14 | ibid. |

| 15 | ‘Synopsis’, The Rainbow Passage official website, <https://therainbowpassage.com/synopsis/>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 16 | Michael Renov, The Subject of Documentary, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2004, pp. 216–29. |

| 17 | Akkadia Ford, ‘Regional & Queer: Refusing to Be Invisible, Creating Queer Space in a Non-queer World’, Cybergeo: European Journal of Geography, 10 February 2017, p. 3, available at <https://journals.openedition.org/cybergeo/27952?lang=en>, accessed 24 August 2020. |

| 18 | Screen Australia, Seeing Ourselves, op. cit., p. 24. |