In 2015, Trevor Paglen began his most ambitious project, Orbital Reflector. A multimillion-dollar artwork that would take the form of a satellite, it would be launched into space, then deploy a 100-foot-long reflective balloon that could be seen from Earth, before ultimately burning up.[1]See Orbital Reflector official website, <https://www.orbitalreflector.com/>, accessed 19 May 2022. This grand conceptual endeavour is a natural subject for a documentary, with Unseen Skies (Yaara Bou Melhem, 2021) synopsised upon its Sydney Film Festival premiere as ‘Visionary American artist […] attempts his most audacious project yet’.[2]‘Unseen Skies’, Sydney Film Festival website, <https://ondemand.sff.org.au/film/unseen-skies/>, accessed 12 May 2022.

Paglen conceived of the work as a ‘provocation’.[3]Trevor Paglen, ‘Let’s Get Pissed Off About Orbital Reflector’, Medium, 30 August 2018, <https://medium.com/@trevor.paglen_21030/lets-get-pissed-off-about-orbital-reflector-44ef70feb9bc>, accessed 19 May 2022. The fact that the project has no military, commercial or scientific value – that it’s, to borrow the conservative-hot-take line, a waste of money – makes it ‘the exact opposite of everything else that’s been put into space’, as the artist puts it in Unseen Skies. ‘Let’s think about what the world’s militaries are doing in space,’ he says, in a television interview seen during the documentary. ‘Let’s think about what the world’s corporations are doing in space. Let’s think about the ways in which these shared resources are being used, towards what ends, to benefit whom.’

Orbital Reflector may be Paglen’s most audacious project, but it’s also just one artwork in a career filled with them. And, in turn, Unseen Skies is a film about so much more than observing one daring undertaking. Bou Melhem, an award-winning Australian journalist making her feature filmmaking debut, had initially planned to make a short film on the artist for the SBS TV series Dateline in 2012, covering the work he was then doing photographing remote military bases and black sites in the American desert. Taking in the totality of Paglen’s oeuvre, Unseen Skies becomes an exploration of the politics and power of the captured image: from the historical development of photography for military reconnaissance through to the contemporary surveillance state, a digital dystopia in which tech giants operate with impunity.

‘We’re trying to make a film for the historical record, to show you this particular moment that we’re in,’ Bou Melhem says, her words echoing Paglen’s own desire to make art that can ‘help us learn how to see the historical moment that we live in’. That historical moment is, of course – to borrow a line from Shoshana Zuboff’s groundbreaking writing[4]See Joanna Kavenna, ‘Shoshana Zuboff: “Surveillance Capitalism Is an Assault on Human Autonomy”’, The Guardian, 4 October 2019, <https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/oct/04/shoshana-zuboff-surveillance-capitalism-assault-human-automomy-digital-privacy>, accessed 12 May 2022. – the age of surveillance capitalism. ‘What do we do when it comes to tech giants and the power they have, and how unregulated they are?’ Bou Melhem asks, out to interrogate ‘how unquestioning we’ve been about the use of these technologies, how unaware we are about how our data is being used and about the lack of transparency’.

Unseen Skies becomes an exploration of the politics and power of the captured image: from the historical development of photography for military reconnaissance through to the contemporary surveillance state, a digital dystopia in which tech giants operate with impunity.

Unseen Skies opens with a visual flourish introducing this wide-ranging context, a montage of historical photographic and technological developments: advancements in capturing microscopic and high-speed images and their militarisation; the space race as televised event; and the recent rise in citizen video, body cameras, CCTV, biometric readings and facial recognition, with famous faces (John F Kennedy, Edward Snowden, Mark Zuckerberg) scattered throughout. ‘Our governments, working in concert, have created a system of worldwide mass surveillance, watching everything we do,’ Snowden says. ‘A child born today will grow up with no conception of privacy at all.’

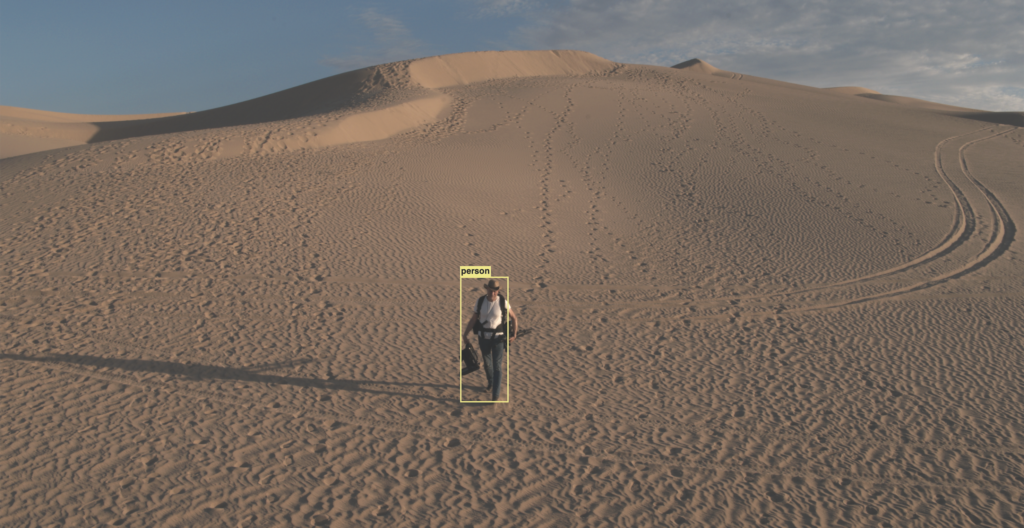

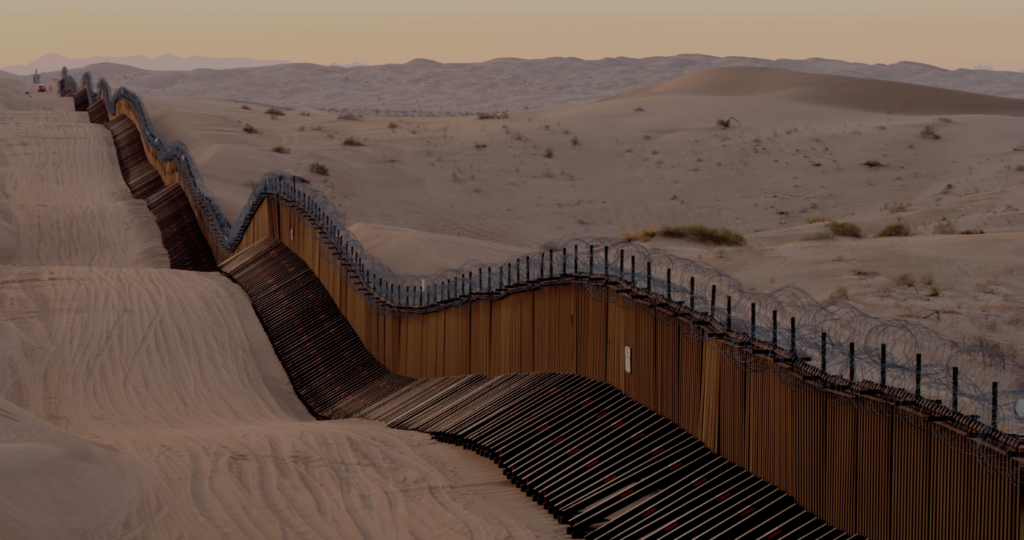

We first meet Paglen – who served as a cinematographer on Laura Poitras’ covert Snowden documentary Citizenfour (2014) – taking photographs on the Algodones Dunes on the US–Mexican border. We see him introduced at the beginning of an artist’s talk – ‘His work on state surveillance and governmental secrecy has never been more relevant’ – before hearing him describe, in more offhand fashion, how growing up in the punk scene helped him ‘understand the relationship between art and politics’ and question society’s hidden systems. ‘I’ve been always suspicious of power and have always questioned that,’ Paglen says. ‘Any kind of power is always exerted at the expense of somebody else.’

Bou Melhem espouses a similar worldview – ‘I’ve always been interested in power and how it works,’ she offers – when recounting her own history as journalist–turned–documentary filmmaker. In either discipline, she believes, there is the same impetus: ‘We can question the assumptions we have about the way the world works and try to change that.’ Bou Melhem says she’s ‘always been interested in people who push the status quo and are trying to solve seemingly intractable problems’, citing a video portrait[5]‘Maria Ressa: War on Truth’, Witness, Al Jazeera, 18 February 2019, available at <https://www.aljazeera.com/program/witness/2019/2/18/maria-ressa-war-on-truth>, accessed 13 May 2022. she made of Maria Ressa, a Filipina-American disinformation campaigner who went on to win the Nobel Peace Prize for her ‘efforts to safeguard freedom of expression’.[6]See Girlie Linao, ‘“A Triumph of Truth over Lies”: Joy in the Philippines over Maria Ressa’s Nobel Prize Win’, The Guardian, 12 October 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/oct/12/a-triumph-of-truth-over-lies-joy-in-the-philippines-over-maria-ressas-nobel-prize-win>, accessed 13 May 2022. Working in feature filmmaking for the first time, Bou Melhem was excited by the ‘creative and artistic scope’ and sense of freedom that is absent in journalism. But at her ‘core’, she says, ‘I feel like I’m very much a journalist’.

What results is a documentary that embraces its thematic breadth, an interrogation of the contemporary moment that begins as a portrait of one man before expanding to a bigger-picture canvas. Unseen Skies does this without voiceover, explainers or infographics, aided in such by Paglen’s artistic history and natural eloquence. He’s explored surveillance technologies through art for two decades, since the dawning of the War on Terror, when ‘secret infrastructure for warfare was taking hold all over the world’. In that context, Paglen cites Derek Gregory’s notion of post-9/11 US imperialism as ‘the everywhere war’,[7]See Derek Gregory, ‘The Everywhere War’, The Geographical Journal, vol. 177, no. 3, September 2011, pp. 238–50. where battles were waged through systems of information and control, and as much on the United States’ own populace as on any foreign enemy.

Paglen photographs military bases and covert sites, the hidden off-map wilderness areas where only those with clearance would ever go. His 2015 installation 89 Landscapes presented a series of static video images that silently observe a host of sites, its individual works given factual names that are at once banal and sinister (like Chemical and Biological Weapons Proving Ground; Dugway, UT; Distance ~ 42 miles; 10:51 a.m., or The Black Sites: The Salt Pit, Northeast of Kabul, Afghanistan).

He also photographs classic vistas – skies and mountains – that would seem timeless were it not for the interruption of a drone flying through, its presence pinning each image to the contemporary moment. Another grand landscape series finds him replicating the images that Timothy H O’Sullivan took during nineteenth-century Department of War expeditions to survey newly appropriated US territories in Arizona and New Mexico[8]See Margaret Regan, ‘The Life of Timothy H. O’Sullivan’, Tucson Weekly, 13 March 2003, <https://www.tucsonweekly.com/tucson/the-life-of-timothy-h-osullivan/Content?oid=1071872>, accessed 16 May 2022. (reconnaissance being a photographic forerunner of surveillance); while a series of works through 2015–2016 involved Paglen photographing undersea fibre-optic cables, the tactile infrastructure underpinning the surveillance state.

And his work is not just limited to the earthbound or aquatic: Paglen has also spent decades photographing satellites, which he sees as loaded with symbolism. ‘What does it mean to be looking at the sky in the twenty-first century?’ he asks in the film. ‘Lo and behold, it’s inhabited by reconnaissance satellites and space junk.’ An extension of terrestrial infrastructure and bearing hallmarks of the Cold War, satellites have aided in erecting a global surveillance apparatus. And, like so much of the refuse of the Anthropocene, they will outlive us, remaining for millions of years in space – like the rings of Saturn, Paglen blithely puts it, except that ‘the rings of Earth are made out of dead machines’.

His photographs – which, again, have names like MILSTAR 6 from Glacier Point (Strategic and Tactical Relay Satellite; USA 169) and DMSP F16 over Monument Valley, Navajo Nation (Military Meteorological Satellite; 2003-048A) – look at these human-made constellations, telling stories about the ‘occupation of the sky’, the evolution of warfare, the surveillance state (he calls one subject an ‘eavesdropping satellite’) and nascent systems of power. ‘Satellites weren’t invented because we wanted to talk to each other around the world,’ Paglen notes. ‘Satellites were invented because we wanted to shoot nuclear missiles to the other side of the world.’

Orbital Reflector grew from thinking about what ‘the opposite of weaponised space’ would be, Paglen dreaming of inserting art into an artless space. Working in concert with the Nevada Museum of Art – and, among many, aerospace engineer Zia Oboodiyat – the artist spent years on a highly complex logistical undertaking. Perhaps inevitably, the documentary shows this project turning into a quixotic quest, with all the ambition and financial capital marshalled ultimately being stalled by bureaucracy and politics. Federal regulators control what can be sent into space, and they have an obvious distaste for the project. It’s eventually launched (from a military base, on a rocket also delivering surveillance satellites – an irony noted by Paglen), but never gets to deploy, effectively killed by the 2018–2019 US government shutdown.[9]See Naomi Rea, ‘Artist Trevor Paglen’s $1.5 Million Orbital Reflector Is Officially Lost in Space Thanks to President Trump’s Government Shutdown’, Artnet News,2 May 2019, <https://news.artnet.com/art-world/trevor-paglen-orbital-reflector-lost-space-1533073>, accessed 16 May 2022.

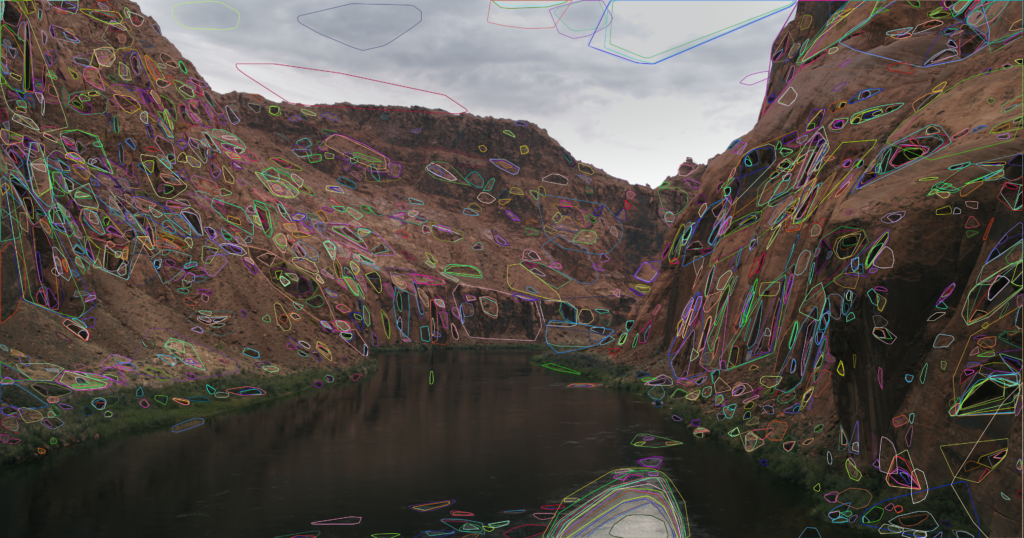

Were Unseen Skies just about this one project, this failure might scan as an anticlimax. But Bou Melhem has bigger fish to fry. When Paglen and AI researcher Kate Crawford create Training Humans, an exhibition exploring the politics and prejudices of computer vision systems, the director matches them by running sections of her own film through such software – faces she’s filmed being assessed and categorised according to detected identities or emotions. This act of ‘breaking the fourth wall’, she says, is a way of both subverting and owning up to the hierarchies of power in documentary filmmaking. Another notable work of Paglen’s runs René Magritte’s This Is Not an Apple through the same object-recognition algorithm, which identifies it as not a painting of an apple, but an apple itself (Magritte called his famous earlier counterpart to this artwork The Treachery of Images; Paglen calls his The Treachery of Object Recognition).

AI, Paglen says, is ‘anything but’ objective and neutral; rather, it propagates a worldview dictated by the state or Silicon Valley, in which coded judgements create a climate of ‘extreme conformity’.

AI, the artist says, is ‘anything but’ objective and neutral; rather, it propagates a worldview dictated by the state or Silicon Valley, in which coded judgements create a climate of ‘extreme conformity’. Just as Paglen’s artwork teases out ‘what kinds of values are hardwired into computer-vision systems’, Bou Melhem hopes that her film can serve as a record of this moment, in which human life has been turned into ‘behavioural surplus’ – data-mined and sold to advertisers – and surveillance mechanisms have reached the point of ubiquity. ‘If you own a phone, can privacy even be possible anymore? Can you even be a private individual in your private life?’ she asks. ‘If data is the new oil, and human beings are the new natural resource being mined for that data, then how did we get to this point?’

In turn, Paglen and Bou Melhem each connect this contemporary moment back to the historical record, in illuminating fashion. ‘Ways of seeing are never natural,’ Paglen says. ‘There’s always forms of power inherent in those ways of seeing.’ Colonial land surveys, early photographic advancements leading to development of nuclear weapons, MIT and Stanford University developing facial-recognition technology, the NSA and Facebook getting into bed together, and data extraction becoming the dominant twenty-first century business model: ‘These are not just abstract lineages,’ Paglen points out. ‘You see all of these convergences of technology, military [and] the appropriation of landscapes.’ This is, according to Bou Melhem, what Unseen Skies is trying to show in its big-picture presentation: that ‘this historical context is really important in understanding how we got to this present moment’.

These ideas (climactically) converge in the performance piece Sight Machine, Paglen’s collaboration with the Kronos Quartet. As the musicians, on stage in London, play a movement from the 1988 Steve Reich composition Different Trains, facial-recognition software judges the footage of them on stage, interpreting who they are and how they’re feeling. Such concrete – and sometimes comically misapplied – labelling stands in stark contrast to the power of music, which, Paglen believes, ‘speaks to us on some pre-cognitive level’. Reich’s own grand conceptual work is about how trains – once cheery symbols of human technological progress and advancement – became instruments of humanity’s most horrifying crime, transporting prisoners to Nazi death camps in World War II.

‘Can we imagine there’s a parallel between that story of technology and the story of technology that we find ourselves within right now?’ Paglen asks, rhetorically. Bou Melhem underlines that notion in a subtle piece of juxtaposition. On screen, we witness the Kronos Quartet perform only the first movement of Different Trains, ‘I. America – Before the War’, which is about the optimism of new technology and new frontiers. But when the closing credits for Unseen Skies roll, we hear the second movement, ‘II. Europe – During the War’, in which this technology is turned into an instrument of terror. This placement was made, Bou Melhem explains, to suggest its resonance with the here and now. With technology selling human existence as advertising grist, notions of privacy being eroded by ‘terms and conditions’ clickwrap, misinformation and propaganda supplanting objective truths, and social media platforms being abused to undermine democratic institutions, we’re living in a dark historical time. ‘I think we’re there,’ Bou Melhem says. ‘I think we’re in that moment right now.’

Endnotes

| 1 | See Orbital Reflector official website, <https://www.orbitalreflector.com/>, accessed 19 May 2022. |

|---|---|

| 2 | ‘Unseen Skies’, Sydney Film Festival website, <https://ondemand.sff.org.au/film/unseen-skies/>, accessed 12 May 2022. |

| 3 | Trevor Paglen, ‘Let’s Get Pissed Off About Orbital Reflector’, Medium, 30 August 2018, <https://medium.com/@trevor.paglen_21030/lets-get-pissed-off-about-orbital-reflector-44ef70feb9bc>, accessed 19 May 2022. |

| 4 | See Joanna Kavenna, ‘Shoshana Zuboff: “Surveillance Capitalism Is an Assault on Human Autonomy”’, The Guardian, 4 October 2019, <https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/oct/04/shoshana-zuboff-surveillance-capitalism-assault-human-automomy-digital-privacy>, accessed 12 May 2022. |

| 5 | ‘Maria Ressa: War on Truth’, Witness, Al Jazeera, 18 February 2019, available at <https://www.aljazeera.com/program/witness/2019/2/18/maria-ressa-war-on-truth>, accessed 13 May 2022. |

| 6 | See Girlie Linao, ‘“A Triumph of Truth over Lies”: Joy in the Philippines over Maria Ressa’s Nobel Prize Win’, The Guardian, 12 October 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/oct/12/a-triumph-of-truth-over-lies-joy-in-the-philippines-over-maria-ressas-nobel-prize-win>, accessed 13 May 2022. |

| 7 | See Derek Gregory, ‘The Everywhere War’, The Geographical Journal, vol. 177, no. 3, September 2011, pp. 238–50. |

| 8 | See Margaret Regan, ‘The Life of Timothy H. O’Sullivan’, Tucson Weekly, 13 March 2003, <https://www.tucsonweekly.com/tucson/the-life-of-timothy-h-osullivan/Content?oid=1071872>, accessed 16 May 2022. |

| 9 | See Naomi Rea, ‘Artist Trevor Paglen’s $1.5 Million Orbital Reflector Is Officially Lost in Space Thanks to President Trump’s Government Shutdown’, Artnet News,2 May 2019, <https://news.artnet.com/art-world/trevor-paglen-orbital-reflector-lost-space-1533073>, accessed 16 May 2022. |