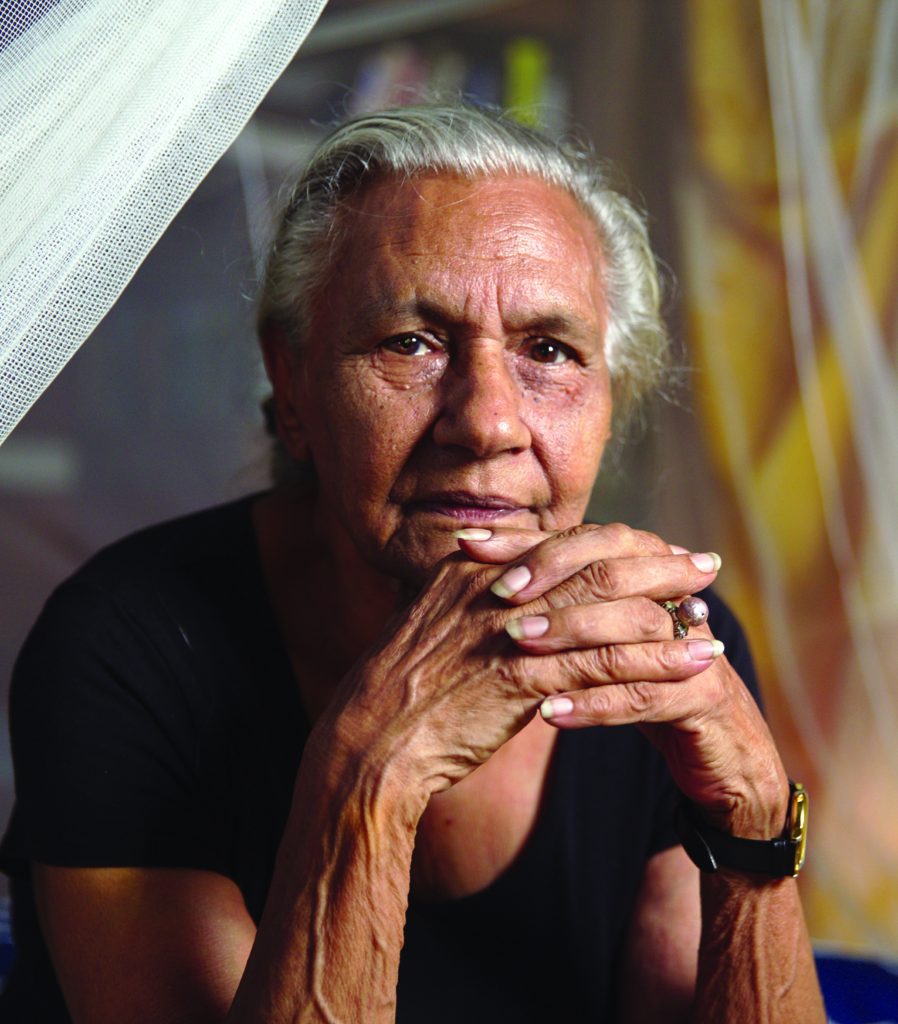

I’m overcome with tears almost from the start. The subject of She Who Must Be Obeyed Loved (Erica Glynn, 2018) is Alfreda ‘Freda’ Glynn, a powerful then-78-year-old Kaytetye matriarch whose expressions and movements – the way she sings out ‘True?’ with a hearty laugh, just like my mum does, and just like my nan used to do – make me homesick.

Mum is crook with a chest infection during NAIDOC Week and spends a lot of it at home, resting but glued to NITV. She lives in a little town on Yorta Yorta Country. After watching the film, she calls me to ask if I’ve seen it.

‘I have, Mum. It’s so beautiful. I’m actually going to be writing about it.’

Mum’s pleased and tells me that she can see her mother – my Nan Rosie – in Alfreda: the way she moves around her kitchen, doing her crossword and gardening, making her cuppa. I get a big, sad lump in my throat and listen instead of resisting Mum’s nostalgia and yearning for people long gone like I used to, when I was younger and awkward with Mum’s honest pain. Before I got healed. I say, ‘True, Mum? That’s beautiful. I saw you, too, in Aunty Freda.’

We go quiet for the past and for all those loved and cherished ones we have lost – so many relatives gone too young and too soon.

I cry even though I don’t know Aunty Freda. Her dignity reminds me of my old people; she is so much like our matriarchs, and makes me think of their stories. The maker of She Who Must Be Obeyed Loved, who is also her daughter, initially tries to paint a picture of Alfreda’s profound legacy in Aboriginal radio and television: after having worked as a stills photographer, she co-founded the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association (CAAMA) and, later, Imparja TV, a career that included an epic battle with media magnate Kerry Packer.[1]See Philip Batty, ‘Freda and Me: The Birth of CAAMA, Imparja and Indigenous Media in Australia’, Wakefield Press blog, 22 October 2018, <http://www.wakefieldpress.com.au/blog/2018/10/freda-birth-caama-imparja-indigenous-media-australia/>, accessed 13 August 2019. But Alfreda chides Erica – and us viewers – with firmness and love: ‘I’ve been telling youse these stories for years and nobody ever listened. And suddenly now everyone wants to know.’ Alfreda has another story to tell, and her daughter submits.

Erica approaches She Who Must Be Obeyed Loved with an insider view that is intimate and trusted, but also with something new – a directorial method that Alfreda at first isn’t comfortable with. We see the filmmaker in conversation with her mother, asking questions and gently directing her within the broader narrative. This is a film that is not only telling a familial story, but told by family: granddaughter Tanith Glynn-Maloney came on as producer, and one of Alfreda’s sons, renowned filmmaker Warwick Thornton, makes a brief appearance. At its core, however, this is an Aboriginal woman’s story, told by Aboriginal women.

Early in the film, Alfreda’s everyday routine of a cuppa and a crossword becomes stilted and she resists the camera’s presence. But, minutes into this story, she begins to tell deeper stories that have remained dormant, unspoken and unresolved.

*

Nan Rosie never spoke of her traumas, or those of her mother or sisters. She didn’t complain when she was in agonising pain from cancer. One of the white nurses at the Echuca hospital on Yorta Yorta Country where Nan stayed at the time even commented that ‘these Aboriginal women never complain’. My grandmother knew that complaining was futile for Aboriginal women, and that speaking of past wounds could be, too. It’s an idea she shared with Aunty Freda’s mother, nicknamed ‘Topsy’, who used to say that the past ought to be left in the past. Yet that same Echuca hospital was also a place that, in the 1950s, segregated my grandmother and other Aboriginal women to give birth on the verandah, outside the actual building.

Many Aboriginal elders, especially women, bore so much of the brute force of colonial violence, sexual subjugation and slave labour. Black American theorist bell hooks has pointed out that female slaves in colonial US society did field work as well as indoor tasks, whereas men were rarely made to do so-called ‘women’s work’.[2]bell hooks, Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism, Pluto Press, London, 1982 [1981], pp. 21–3. The situation in Australia was much the same; as Alfreda recounts of Topsy’s experiences, Aboriginal women, much like black American female slaves, were at the ‘beck and call’ of white people, night and day. And so they suffered the indignity of not only doing ‘women’s work’ indoors – at station houses and the homes of the wealthy elite in places like Vaucluse in Sydney – but also assisting their male counterparts with ‘men’s work’, such as branding cattle outside in yards. These were things that Topsy did – that my grandmother did.

The extent of colonial violence also extended to interpersonal relationships. Erica gently draws from Alfreda the story of her white father, and Alfreda touches on ‘half-caste’ children, who were treated as a ‘problem’ for white men and their white wives. Lest they make their white families uncomfortable, these children were hidden from sight and removed from their black mothers. My mum tells me this is such a common story for Aboriginal women – and, while largely untold, it’s one that is gradually being brought to light. On the ABC’s Anh’s Brush with Fame, for instance, Goa, Gunggari and Wakka Wakka actor, writer and director Leah Purcell recounts a similar story of how her white father, a butcher, kept her and her Aboriginal mother – his mistress – a secret, and separate from his white wife and children.[3]See Anh’s Brush with Fame, Season 4, Episode 4.

These dynamics can manifest in more insidious ways, too – as my own family experiences attest. My mother was fathered by a man of Chinese, Greek and Irish blood, in a loveless, arranged marriage that my grandmother barely tolerated. Mum recalls that, during her parents’ entire relationship – during which they had four children – she never saw them speak to each other. My own father is an Italian migrant, whose violence my mother tolerated for a couple of years before she left him. It has yielded, for me, a difficult and estranged relationship with him.

This is a film that is not only telling a familial story, but told by family: granddaughter Tanith Glynn-Maloney came on as producer, and one of Alfreda’s sons, renowned filmmaker Warwick Thornton, makes a brief appearance. At its core, however, this is an Aboriginal woman’s story, told by Aboriginal women.

In the film, Erica asks Alfreda whether seeing a photo of her white grandfather stirs anything in her; she unequivocally answers ‘no’. ‘I’m not really involved with that family, even though I might have their blood,’ she says, and then later: ‘I’d never even spoke to my father, ever.’ In turn, the history of her white family’s old telegraph station, which was fashioned into barracks for her and the other ‘half-caste’ children, later erased – ‘whitewashed’, in her words – their very existence. The presence of these children was an inconvenient truth.

Perhaps Aunty Freda doesn’t wish to talk about her media legacy because her legacy includes her children and grandchildren – not only as screen storytellers in their own right, but also as individuals who bring her the most pride. We see her express unconditional love for them, despite her hardships and struggles. This thread of unconditional love is woven throughout the film.

My own two children are fathered by two different white men. I see up and down our line of Aboriginal motherhood – Nan Rosie, my mother, myself – women who are nurturing Aboriginal children to embrace their genealogy, their identities, their culture, families and communities.

*

Reflecting on how she put her kids into homes so she could move interstate to study in Adelaide, Aunty Freda tells her grown children that she felt it was necessary ‘to bury any feelings [she] had in [her]’: ‘I used to say to you kids, “Oh well, get on with it” […] That’s how I survived […] I just lived in airy-fairy land.’

While Erica set out to make a film in search of a specific story, Alfreda has elected to share another. In this way, she is much like many other Aboriginal women: despite your requests, your mother, your nan, your aunty will tell the story she wants and needs to tell – and, perhaps, the story she believes you need to hear. She will often tell you a story about her ‘choice’ because she doesn’t want to centre herself, doesn’t want to platform her own voice as the most important, because she is used to not being heard. She is used to being historically silenced, to living with silence.

Despite Alfreda’s hesitation to tell the story of CAAMA and Imparja again, this story does get told. It becomes lovingly woven into the counter-narrative she wishes to pursue: that of the trail and truth of what happened to her grandmother, who, Alfreda was informed, was the victim of a massacre during the colonisation of central Australia. Through her own legacy, Alfreda challenges what Ngugi / Wakka Wakka scholar Tracey Bunda has called the ‘colonised creation of the object black woman’ – a construct that can be subverted by ‘speaking of ourselves, our emotions and our histories [as] the essence of our social, political and spiritual being’.[4]Tracey Bunda, The Sovereign Aboriginal Woman, in Aileen Moreton-Robinson (ed.), Sovereign Subjects: Indigenous Sovereignty Matters, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2007, p. 77.

Aboriginal documentary makers, in particular, create ongoing stories that form part of a larger narrative about Aboriginal peoples’ history and future, and present the truths, nuances and insider languages that mob are familiar with. Black films embody a storytelling mode that favours close proximity, pushing against the colonial documentary framework that strives for objectivity. This is the personal as political. Aboriginal documentary storytellers speak directly to lived experience; as Eualeyai/Kamillaroi academic and filmmaker Larissa Behrendt has asserted:

Directing film allows for authorial voice. As Aboriginal researchers, we do not assume to be objective. We know there is no such thing. If we thought our position in the world could be passive we wouldn’t introduce ourselves by our nations, our clans, our kinship networks. We place ourselves in the world as an act of sovereignty and it reinforces our worldview.[5]Larissa Behrendt, ‘A Personal Reflection on Self-determining Documentary Filmmaking Practice’, Artlink, issue 39:2, June 2019, available at <https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/4757/a-personal-reflection-on-self-determining-document/>, accessed 13 August 2019.

Black women’s perspectives and the ‘herstories’ they communicate through storytelling are not only expressions of Aboriginal matriarchy, but also, as Behrendt describes them, self-determined, decolonial and sovereign acts[6]ibid. that are performative and documented means of surviving the injuries of the colonial project, both historical and continuing. Each story speaks of and to the violence experienced by black women in this country as ongoing trauma.

Patriarchal, colonial narratives of history have rendered black women’s voices much quieter – requiring us to fight for spaces in which to be heard. Destructive notions such as ‘black velvet’[7]A term of sexualisation used by white men during Australia’s early colonial period to refer to Aboriginal women; see Sandra Phillips, ‘Black Velvet: Redefining and Celebrating Indigenous Australian Women in Art’, The Conversation, 9 May 2016, <https://theconversation.com/black-velvet-redefining-and-celebrating-indigenous-australian-women-in-art-56211>, accessed 13 August 2019. that point to our supposed sexual availability and lack of authority haunt Aboriginal women, leaving a spreading stain. With projects like She Who Must Be Obeyed Loved, however, Aboriginal women seize back authorship of our lives, establishing and enacting the parameters within which our stories unfold and through which we can protect other stories yet to come.

Perhaps Aunty Freda doesn’t wish to talk about her media legacy because her legacy includes her children and grandchildren – not only as screen storytellers in their own right, but also as individuals who bring her the most pride. We see her express unconditional love for them, despite her hardships and struggles.

The indignities and injustices suffered by Aboriginal women are spoken of in She Who Must Be Obeyed Loved in a way that I recognise. Having grown up Aboriginal and female, I have seen such discussions happen in hushed tones and coded talk because the shame of violence inflicted on our bodies, our beauty, our vulnerability is too raw. The narrative that frames us as strong, resilient backbones – for our children, for our families – also resonates, but it hides the wounds from which we are yet to heal.

Alfreda’s life work has been spent platforming the stories of others, and, even in a documentary about her own life, she again wants to tell the stories of others: in this case, those of her beloved mother and grandmother. Aunty Freda’s successes are a testament to her strength and vision; through Erica’s camera, we see her radiate a fierce sense of self and an innate grace. Her media-industry contributions for Aboriginal people, and for Australia more broadly, are highly significant, and this film – so tenderly directed – lays out the work she has achieved against incredible odds. At the same time, it respects and submits to her resolve to tell her family’s story alongside her own, and to grapple with the many hurts that call forth from the past.

Endnotes

| 1 | See Philip Batty, ‘Freda and Me: The Birth of CAAMA, Imparja and Indigenous Media in Australia’, Wakefield Press blog, 22 October 2018, <http://www.wakefieldpress.com.au/blog/2018/10/freda-birth-caama-imparja-indigenous-media-australia/>, accessed 13 August 2019. |

|---|---|

| 2 | bell hooks, Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism, Pluto Press, London, 1982 [1981], pp. 21–3. |

| 3 | See Anh’s Brush with Fame, Season 4, Episode 4. |

| 4 | Tracey Bunda, The Sovereign Aboriginal Woman, in Aileen Moreton-Robinson (ed.), Sovereign Subjects: Indigenous Sovereignty Matters, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2007, p. 77. |

| 5 | Larissa Behrendt, ‘A Personal Reflection on Self-determining Documentary Filmmaking Practice’, Artlink, issue 39:2, June 2019, available at <https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/4757/a-personal-reflection-on-self-determining-document/>, accessed 13 August 2019. |

| 6 | ibid. |

| 7 | A term of sexualisation used by white men during Australia’s early colonial period to refer to Aboriginal women; see Sandra Phillips, ‘Black Velvet: Redefining and Celebrating Indigenous Australian Women in Art’, The Conversation, 9 May 2016, <https://theconversation.com/black-velvet-redefining-and-celebrating-indigenous-australian-women-in-art-56211>, accessed 13 August 2019. |