Yolanda Ramke and Ben Howling are among that fortunate breed of filmmaker who builds a reputation on the strength of one undeniably good short film. In this case, their 2013 Tropfest effort, Cargo – a heartfelt, elegiac riff on the zombie subgenre – put them on the map with several million views on YouTube, soon after which they went on to sign with powerbrokers Creative Artists Agency (CAA).[1]Causeway Films, Cargo press kit, 2017, p. 6. It’s worth recalling that similar good fortune struck for Leigh Whannell and James Wan, whose Saw prototype – made when they were recent RMIT graduates – was immediately snapped up by Hollywood and made into their first full-length feature, which premiered in 2004.[2]Wan took on directorial duties, with Whannell responsible for the script; see Rachel Wells, ‘A Saw to Film Barriers’, The Age, 25 November 2004, <http://www.theage.com.au/news/Film/A-saw-to-film-barriers/2004/11/24/1101219614917.html>, accessed 1 November 2017.

It’s a brave new world. Ramke and Howling tell me their decision to develop a specifically Australian property as their first feature film was a creative rather than political one. Two of their producers, US-based Russell Ackerman and John Schoenfelder of Addictive Pictures, recognised that a localised take on the zombie subgenre would be a selling point, not a disadvantage. Ackerman and Schoenfelder then approached Sydney-based producers Sam Jennings and Kristina Ceyton of Causeway Films, and – with support from Screen Australia and the South Australian Film Corporation – the feature-length Cargo began production in 2016.

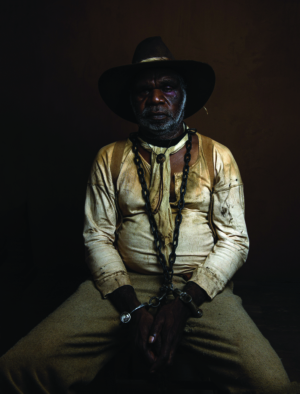

A First Nations approach to zombies

Ramke and Howling’s collaboration with Indigenous artists on Cargo has been an integral part of the project. The press kit summarises the film as a

father/daughter love story, which just so happens to unfold against the backdrop of a deadly outbreak. The film explores two parallel tales of familial devotion: an infected man’s mission to seek a new home for his infant daughter and conversely, a young Indigenous girl’s quest to save the soul of her infected father.[3]Causeway Films, op. cit., p. 3.

Ramke elaborates on the narrative and themes:

You’ve got this English man [played by Martin Freeman] in a harsh Australian environment and navigating a relationship with Indigenous characters […] Civilisation as we know it has collapsed, and it’s actually the Indigenous inhabitants of the country [who are] flourishing […] There’s the idea that this pandemic is something that we [settlers] unleashed on ourselves because of a lack of understanding of country […] and poisoning the land [and] pillaging for natural resources.

The team hired an Indigenous consultant to give initial notes on the draft script, and then, on a later draft, began collaborating with Indigenous writer Jon Bell, who previously worked on TV series Redfern Now and Cleverman. Ramke describes the experience as ‘inspiring and really enriching’:

This sounds like a really wanky thing to say, but it really was […] I think any filmmaker should be very wary of cultural appropriation, very determined not to do that […] We were – in so many ways – completely ignorant about so many things and so, so hungry to rectify that.

Bell stayed on board throughout the process, and the production was assisted by locations manager Mason Curtis in facilitating a dialogue with local elders of the Adnyamathanha people of the Flinders Ranges. Ramke recounts:

One of the missteps that can happen [with cross-cultural collaboration] would be to try and adopt Dreamtime stories – stories that are not ours, that aren’t our property. So we knew we absolutely did not want to […] use Indigenous culture or spirituality to explain plot events.

‘We wanted to make sure that, if we were going to have Indigenous characters in the story, they had a point of view that was their own … and that they’re not just there purely to support the white characters’ narratives.’

—Yolanda Ramke

Our child character [played by Simone Landers] has a childish perception of [the zombie threat] but […] what we were trying really hard to avoid was this sort of ‘magical Aboriginal character’ cliché […] We also wanted to make sure that, if we were going to have Indigenous characters in the story, they had a point of view that was their own, that was deep, that was fleshed out – that the characters have their own objectives and goals, and that they’re not just there purely to support the white characters’ narratives.

Road to production

Ramke describes the film’s journey, from treatment to world premiere at the 2017 Adelaide Film Festival, as a dream run. But that doesn’t mean it’s been easy.

Everything’s rolling really fast one minute and then the brakes are on for a bit [… ] Coming towards actually shooting, I think there’s a part of you that’s still thinking, ‘Oh well, this might not actually happen. It might fall over at any minute.’

The leap from short to feature is daunting for any filmmaker, but Ramke and Howling don’t seem lacking in confidence – no doubt held in good stead by their extensive backgrounds in television. They approached the difficult six-week shoot for Cargo with a laid-back stoicism – which bodes well for their careers’ sustainability – and Howling recounts that one of the biggest adjustments was getting used to the rigid structure of a feature film set, wherein roles and tasks are more discrete. Better production values are also a plus, though they do entail managing more people working across a variety of areas. Ramke agrees – problems don’t disappear; they just scale up.

Cargo saw the duo operating with a six-week shoot and a budget that was half of what was recommended to them for the desired outcome; they had to consider how best to realise the script given the schedule and resources at their disposal, and also how to accomplish it all ‘without compromising on the story and the intentions of the film’. According to Howling, gauging a sense of how much action can be shot has been one of the most valuable lessons in moving into longform drama, along with getting a feel for when a scene may have too much complexity on the page.

Yolanda’s script was amazing – and amazingly dense as well […] Some clever, subtle exposition is set up early on, but you start questioning, ‘Well, do we need this level of detail? Can we drop certain things and it will still make sense, it will still be effective?’ Then you get to the edit and you lose entire scenes, anyway […] you’ve got to go through it all just to learn that.

Budget limitations

Ramke recalls that key budget adjustments were implemented on the script level, nearly all of which were made prior to shooting. ‘We were very lucky that our producers Kristina and Sam from Causeway are story-oriented and have backgrounds in that, and are really great sounding-boards.’ But she explains that she and Howling were committed to maintaining their ambitions for the film:

At times, the director in me hated the writer in me because […] the level of our vision that we were striving for was sort of ridiculous […] You’ve got four babies. You’ve got an eleven-year-old girl [Landers] who’s never acted before. You’ve got prosthetics, you’ve got extras, you’ve got stunts and cars and shooting on the water.

As a writer, you think, ‘I’m going to write myself what I would want to watch,’ and you just throw it all on the wall – no holds barred. And then, when it comes to actually executing that, it’s like, ‘Oh shit, who’s actually going to juggle all of these things?’

The film’s post-apocalyptic element meant that the choice of setting would be crucial to world-building. And, predictably enough for a location-driven project, the Cargo team’s biggest challenge was weather. South Australia was in the middle of its wettest winter since 2001, and exterior shots comprise 85 per cent of the film. Various remote sites in the Flinders Ranges were used, meaning travel time also had to be factored in on top of contingencies like flooded roads and bogging. Yet, while scenes were cut and amalgamated, no major compromises were made. ‘Some of the scenes are handheld – some of the more intimate scenes – as much tighter spaces have that […] more raw feel,’ says Ramke.

But knowing also that we wanted to get some expansive landscapes and sense of scale […] we tried not to let [the budget] impact the look that we were going for. That was hugely informed as well by our DOP Geoff Simpson, who’s an absolute veteran.

Two-for-one directors

While the duo have joined the global ranks of genre directors who work as a team – the Spierig Brothers as well as Colin and Cameron Cairnes are notable examples in the Australian context – each had a loose area of specialisation during Cargo’s production. Whereas Ramke gravitated towards matters relating to story and working with actors, Howling was more focused on camera and shooting requirements. According to Ramke, their level of prep was such that they only needed to confer with each other occasionally:

Things change constantly on set […] and, in those instances, often there will be that step to discuss how we’re going to do that, or we’ll talk to the head of department about that. But sometimes, it gets to a point where you just know what the other person is thinking and you speak for one another.

There was also a period on the shoot when the crew was separated into two production units. ‘This was not just B-roll material; it was actually separate scenes,’ says Ramke.

It’s not what you ideally want to be doing, but it was a necessity at that point, and it seemed to work […] We tried to minimise that as much as possible – but, when it comes down to a choice of either getting a scene or not getting a scene, of course you’re going to do it.

Out into the world

With domestic distribution handled by Umbrella, it remains to be seen whether Cargo will fare better at the local box office than its recent genre brethren. From The Loved Ones (Sean Byrne, 2009) and 100 Bloody Acres (The Cairnes brothers, 2012), to These Final Hours (Zak Hilditch, 2013), The Babadook (Jennifer Kent, 2014) and Killing Ground (Damien Power, 2016),Australian audiences have consistently disregarded the best that we have to offer in the genre realm. It’s a complex problem involving perception, marketing budgets and more, but, regardless of Cargo’s commercial performance, it’s already a winner for Ramke and Howling.Both in their thirties, the directors have got an impressive debut under their belts – one that, impressively, has been secured as the first Australian fiction feature under the Netflix originals banner.[4]Andreas Wiseman, ‘Netflix Swoops on World Rights to Martin Freeman Zombie Movie’, Screen Daily, 10 February 2017, <https://www.screendaily.com/news/netflix-swoops-on-world-rights-to-martin-freeman-zombie-movie/5114764.article>, accessed 1 November 2017. They’ve done all of this on their own terms, and in a fashion that genuinely moves Australian genre filmmaking forward.

In promotional material, Ramke and Howling refer to Cargo as ‘an elevated genre film’;[5]Causeway Films, op. cit., p. 3. undeniably, it’s a piece of cinema that emphasises theme and character over, say, visual effects or action. The directors tell me they were inspired by the late George A Romero’s classic zombie flicks, though Cargo straddles both arthouse and mainstream aesthetics. ‘It’s not so stylised that it’s hard for people to digest, or confronting,’ clarifies Howling, ‘[yet] not so commercial that you can predict what’s happening in the next scene.’ Ramke adds that Romero ‘deserves all the credit in the world’:

Those films had a really healthy dose of social commentary from the beginning, so we’re not really inventing the wheel in that regard. [But we] also just tried to do a little world-building with our film, and do a more unusual twist on the way that our zombies operate.

She says they were also careful to not over-explain details, and deliberately decided against providing an overarching rationale for the zombies’ existence or behaviour. ‘You’re sort of throwing the audience in the middle of it and going, “This is what’s happening. This is the assumed knowledge.”’

To end, Howling and Ramke consider the ‘problem’ of being a genre filmmaker in Australia; from their limited perspective as first-time feature directors, they believe a positive change is afoot. ‘We don’t really see enough Australians in genre material,’ says Howling.

But hopefully now, as [genre] becomes more prominent, Australians are starting to buy into the legitimacy of it […] and it just becomes more commonplace. It’s not like, ‘Oh, there’s an Australian attempt at a genre thing’ – it’s just, ‘Here’s an Australian film.’

Endnotes

| 1 | Causeway Films, Cargo press kit, 2017, p. 6. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Wan took on directorial duties, with Whannell responsible for the script; see Rachel Wells, ‘A Saw to Film Barriers’, The Age, 25 November 2004, <http://www.theage.com.au/news/Film/A-saw-to-film-barriers/2004/11/24/1101219614917.html>, accessed 1 November 2017. |

| 3 | Causeway Films, op. cit., p. 3. |

| 4 | Andreas Wiseman, ‘Netflix Swoops on World Rights to Martin Freeman Zombie Movie’, Screen Daily, 10 February 2017, <https://www.screendaily.com/news/netflix-swoops-on-world-rights-to-martin-freeman-zombie-movie/5114764.article>, accessed 1 November 2017. |

| 5 | Causeway Films, op. cit., p. 3. |