And what was the BBC’s reaction to the completed film?

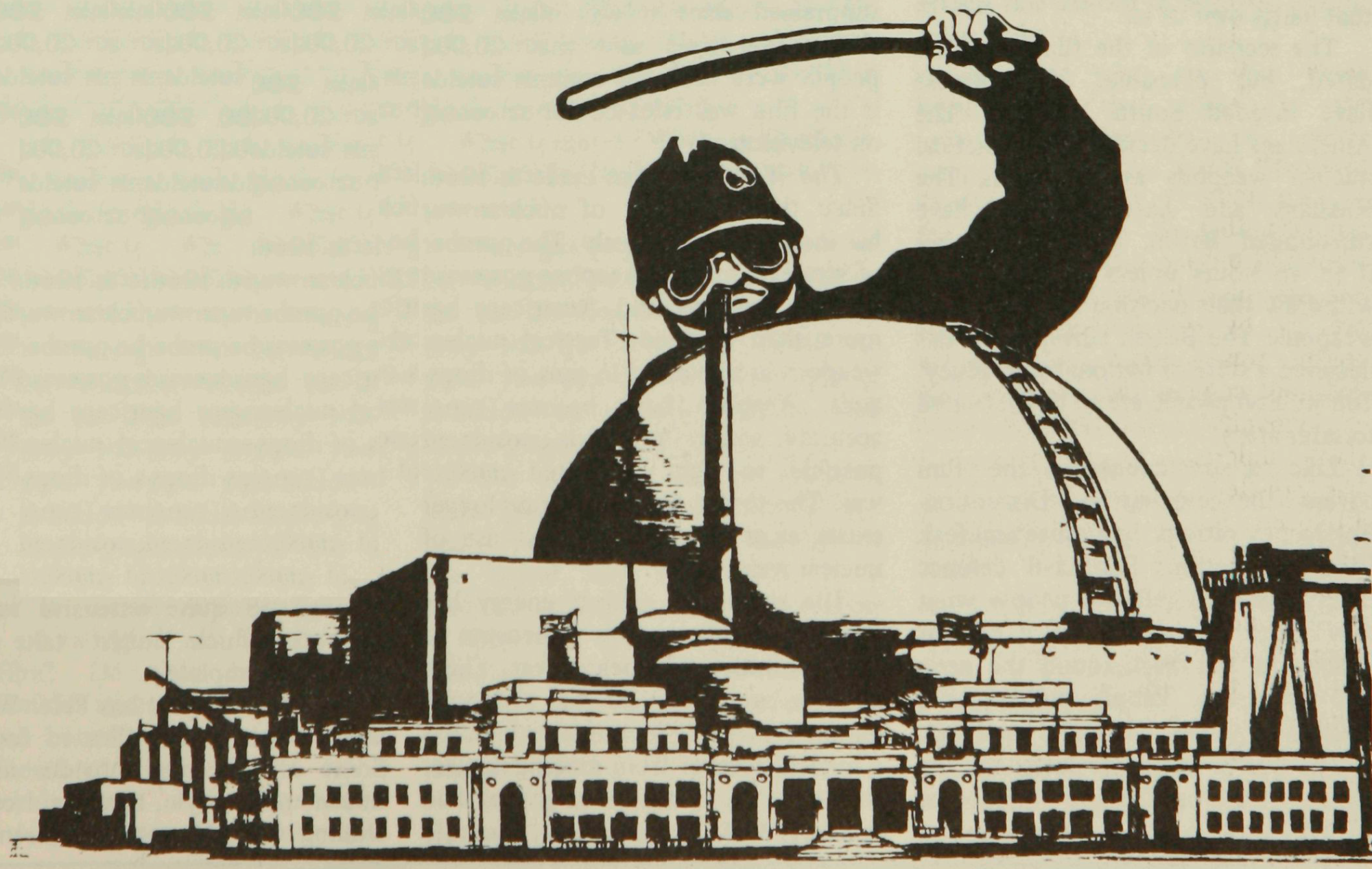

For two months there was silence. Then I discovered that the BBC, despite its “independence”, had secretly shown the film to officials from the Home Office – the Dept. that deals with Civil Defence.

Two months later the BBC announced that the film was banned from TV, but denied that the banning had anything to do with the secret preview by the Home Office. The reason was because the film was “without compassion”, “a bleak view of humanity”, and that “it would alarm children and old people”. It was privately told to me by senior producers in the corridors of the BBC that it could “drive up to 20,000 to suicide”.

But once I had heard about the secret screening, I went public and criticized the BBC in the press. I achieved a certain media coverage of the event as well as the support of a small number of members of the House of Commons.

Then, having decided how the British public would react, the BBC held four private, guarded screenings for selected members of the establishment – senior members of the Armed Forces, Civil Defence and selected media writers. Significantly they weren’t film critics, but defence and diplomatic correspondents. This elite audience without a public representative approved the ban, and thus the British establishment shared the BBC’s responsibility for its own censorship.

The active public campaign forced the BBC to release the film for cinema screenings, but ever since it has been banned from TV in every country of the world.

Could the style of the film have contributed to its banning?

Yes! Anyone who has worked in this awful profession of mine knows that we are just buried under technique, and that every time someone appears with a personal message or a message of commitment, then that person is regarded as an absolute paranoid lunatic and usually gets kicked out of the industry within a year, or kind of eased out, or put under such pressure that he or she starts compromising within a couple of years.

And The War Game clearly sits in that area. I think that one of the reasons why it was banned, though this has never been discussed publicly, is simply because The War Game indicates some of the directions that TV might have taken ten years ago by developing a whole … I don’t know how to put this … but a whole wave of subjectivity and feeling, and force of feeling, instead of this so called objectivity that flattens everything into zero.

I think that because The War Game works so much against the objectivity rule and was passionate and committed, that it broke just about every rule upon which every Western TV network stands. I think that’s also why the film had to be banned. I’m dammed sure that’s why the BBC banned it – not necessarily because of the political implications of its subject matter, but because it threatens the very image of TV itself.

Would you be interested in showing an updated version of the film on television today?

Well I was twice invited to remake The War Game in Germany, but both times the German television companies “unexpectedly” pulled out at the last minute.

But even if one could find a company that would finance a film on this subject, personally speaking, I would refuse to allow it to be transmitted unless under the most stringent conditions.

I would demand that every screening on public TV was followed by public debates on the whole issue of Uranium, Plutonium and the Nuclear Arms Race. These public debates would have to be interwoven with documentary programs containing information to which people are now deprived, and all this should take place weekly over a period of six months or so.

If these arrangements were not made, I would not agree to the TV screening of another War Game. For in 1977, I believe that it is far more dangerous to view The War Game in isolation than to continue to leave it unshown.

Why?

My fear now is that the retrogressive steps taken in the media during the last 10–15 years have increasingly alienated the public from some of the harder realities of our world and our life, to increasingly float all of us on a mental Bahamas trip, and to increasingly saturate us with a kind of Lucille Ball mental musak. Now, in the 1970s the crisis is so serious that if you were to take something like The War Game and suddenly give it to the people in the middle of all the Kojaks, the Lucille Balls, and suddenly, PLONK! The window on the world opens for a moment, the chill wind comes in, people see the vision of thermonuclear war, they viscerally experience it, and they also experience, emotionally and intellectually, the receiving of information on nuclear warfare for the first time in their adult lives. Then the window suddenly slams shut at the end of the film.

A few seconds later: Kojak or Lucille Ball returns.

The person sits there, and the very relevant question is What do they do with that information? What can they do? Might not the experience of The War Game be dissolved for them in the whole miasma? Who is to know that Lucille Ball doesn’t psychologically wash over the first half of The War Game, and then Kojak backwashes over the second half and thus cover it entirely?

Or they sit there and ask “What can I do about this? Why haven’t I heard about all this before?” I think that it is extremely likely that unless there was supportive programming following it so that the experience can assist people to find others with whom they can work positively to grasp these problems, then I feel that the effect would be deflating.

I’m not sure of this, but my feeling is strong enough now for me not to allow the screening of The War Game on TV unless it were accompanied by supportative programs.

You seem to believe that the nuclear issue is more than another vital issue for mankind. It seems to have an over-riding importance for you.

Yes, I believe that the Uranium issue, together with the issue of pollution and a series of other crises, are combining to such a serious degree that we are at a vital watershed in human history.

And an important aspect of all this is, what happens do all the millions of people who receive little bits and pieces on all these issues, who sense the onrushing future with anxiety and dread, who know that they are deprived of political power?

I sense that here in Australia now that your government is about to legalise the export of the Uranium. I sense here these feelings of futility, rage and impotence.

And the situation is all the more critical when we consider that the very conservative media structure in this country (it’s even more conservative than in the U.S.) is depriving people of information on this all important Uranium issue.

You can look through your TV, newspapers and fail to find anything of real substance on the issue of nuclear power.

And the trend seems to go against opening up of information to the people?

Well, I wouldn’t say “seems”, I feel it is. I know that people are being deprived of information. Take any western democracy and you’ll know that 96% of the people are systematically deprived on information, and Australia is definitely among them.

And that lack of public knowledge just before a national decision on this Uranium question which is going to affect the future of the whole world, that is absolutely mind boggling. It’s pure George Orwell.

It’s all the more shame for Australia, for in this country I have been aware of an openness to information and communication which has long since been lost in Britain and Europe. In this short visit I have felt a great demand by all sorts of people for open discussion on these issues.

And what do you say to them?

Well, briefly, that people have to work together, and support each other, and that if they are going to use The War Game, then it must be shown in a context where it will lead to closer contact between the isolated members of an audience and those groups who are working together in response to these issues.