In a film filled with memorable visuals, the most powerful images in Guilty (Matthew Sleeth, 2017) have actually already been seen before. They aren’t the product of the film’s director, but rather of its subject: the now-executed convicted drug smuggler Myuran Sukumaran. Discovering his passion for painting during his incarceration, he made his mark on hundreds of canvases, crafting an array of self-portraits, representations of others and more abstract works. In the documentary, three stand out, all painted in the last hours before his death. One, Time Is Ticking, depicts his own likeness, with a concerned expression on his face and a gaping hole where his heart should be. Another, One Heart, One Feeling in Love, shows a bloody heart painted large in shades of crimson. A third re-creates the Indonesian flag, its top red stripe – which takes up the upper half of the canvas – bleeding over the white stripe below.

First shown to the public via news footage on the morning after Sukumaran’s execution, these paintings have become symbols of the condemned man’s plight – and, with the trio expressing a clear outcry of pain and anxiety from someone facing a certain demise, that’s hardly surprising. They’re Sukumaran’s parting gifts, not only encapsulating his feelings at the toughest time in his life, but also providing everyone else with lasting reminders that his heart stopped beating as a result of an Indonesian firing squad. Proffering an equally strong message, Guilty steps behind and beyond all three in chronicling the seventy-two hours that brought the artworks to fruition. If Sukumaran’s own pieces convey his mindset in his final hours, Sleeth’s film gives them context, while also mounting a rallying cry against its central figure’s ordeal.

Of course, for his last decade alive, Sukumaran’s life was not his own; whether he would live or die became a frequent topic of conversation across Australia, from household chatter to newspaper headlines. Not merely a member of the Bali Nine but dubbed one of its ringleaders, Sukumaran was caught along with eight other Australians as they tried to smuggle 8.3 kilograms of heroin out of Indonesia in 2005.[1]Jano Gibson, ‘Nine Australians Caught in Bali Drug Sting’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 18 April 2005, <https://www.smh.com.au/news/National/Nine-Australians-caught-in-Bali-drug-sting/2005/04/18/1113676689459.html>, accessed 25 May 2018. He was subsequently charged and convicted under Indonesian law, receiving – with his associate Andrew Chan – the death penalty for his involvement.[2]‘Australian Men Sentenced to Death’, BBC News, 14 February 2006, <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/4711208.stm>, accessed 25 May 2018. Appeals followed, both through the judicial system and via pleas for clemency directed towards the Indonesian President. On 25 April 2015, after all avenues of revoking his sentence had been exhausted, Sukumaran was informed that his punishment would be carried out shortly after midnight on 29 April. At the nominated date and time, he was executed alongside Chan and six other prisoners convicted of unrelated drug crimes.[3]Michael Safi & Dina Indrasafi, ‘Bali Nine Pair Among Eight Executed for Drug Offences in Indonesia’, The Guardian, 29 April 2015, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/28/bali-nine-pair-executed-indonesia>, accessed 25 May 2018.

Thanks to a series of poor decisions and the legal ramifications they sparked, many will remember the story of Sukumaran’s life in the above terms; however, that’s a fate that his paintings and Guilty both actively work to change. Neither Sukumaran’s art nor Sleeth’s documentary can alter the outcome of the former’s tale or the details that led him there, but they can shed light on the broader narrative behind his incarceration. His isn’t just a story about punishing a wrongdoer – one who broke the law in a country that penalises crimes such as his with death, specifically – but also a snapshot of society in general’s handling of punishment and rehabilitation, as conveyed through an account of Sukumaran’s last moments.

Indeed, from the outset, Guilty’s stance is obvious. Images of ordinary life in Bali – a just-married couple on the beach, the island’s streets, eateries flying miniature Australian flags on their tables, tourists holidaying – may open the documentary, but the idyll they appear to depict soon fades away. Sleeth accompanies these visuals with radio clips discussing the Bali Nine case, including conflicting opinions, before showing a re-enactment of Sukumaran (played by Adam McConvell) receiving notification of his impending execution. The feature then switches to real news footage of his distraught, pleading mother, Raji, expressing a sentiment the documentary transparently espouses even though its maker is already cognisant of the outcome. ‘Please don’t kill my son,’ she cries, in a visibly distressed state.

Standard though these techniques may seem, both for documentary filmmaking in general and for a film focused on a figure in Sukumaran’s situation, these early moments establish Guilty’s various mechanisms for exploring its topic. Through emotive imagery, particularly of the ocean, Sleeth’s film seeks to evoke the freedom that Sukumaran forever lost, while also endeavouring to express his internal state through the ebbs and flows of the tide. Through comprehensive recreations of the hours leading up to his execution – including his own preparations, the plans of the firing squad charged with the task and the shooting itself – the film casts a detailed eye over the minutiae involved in facing death, and paints a portrait of a man who might have earned a different fate due to his rehabilitation in prison. Through archival footage and audio, it provides context to his plight, as well as arguments for and against his punishment. And, through post-execution scenes with Sukumaran’s mother back in Sydney, it shows the broader effects of her son’s incarceration and death, including the reception of his artwork.

In order to clearly convey the impact of killing Sukumaran, Guilty’s re-creations have two aims: to allow audiences to better know and understand Sukumaran, and to detail exactly what was involved in ending his life.

Visual-artist-turned-filmmaker Sleeth deploys these various elements in his film like brushstrokes on a canvas. Each component speaks to the documentary’s central position: that the death penalty is an extreme measure in any circumstance, and that Sukumaran’s transformation during his time on death row both amplified the punitive effect of his execution and negated the need to eradicate him as an unwanted member of society. The recurring images of the sea channel both the restlessness within Sukumaran in his final days and the release that awaited him, while the film’s use of news materials demonstrates the heightened state of agitation that surrounded his case. It’s the more personal sections of the film that provide insights as well as sentiments, however; unsurprisingly, these constitute the bulk of the documentary.

In order to clearly convey the impact of killing Sukumaran, Guilty’s re-creations have two aims: to allow audiences to better know and understand Sukumaran, and to detail exactly what was involved in ending his life. Both are achieved with precision; though the statement behind the documentary is never in doubt, the craft deployed in fulfilling the feature’s goals remains meticulous. The use of framing significantly contributes to the film’s picture of a rehabilitated inmate, while also showing the impact of his work and changed mindset. Sleeth’s emotive intentions are blatant, but they’re effective.

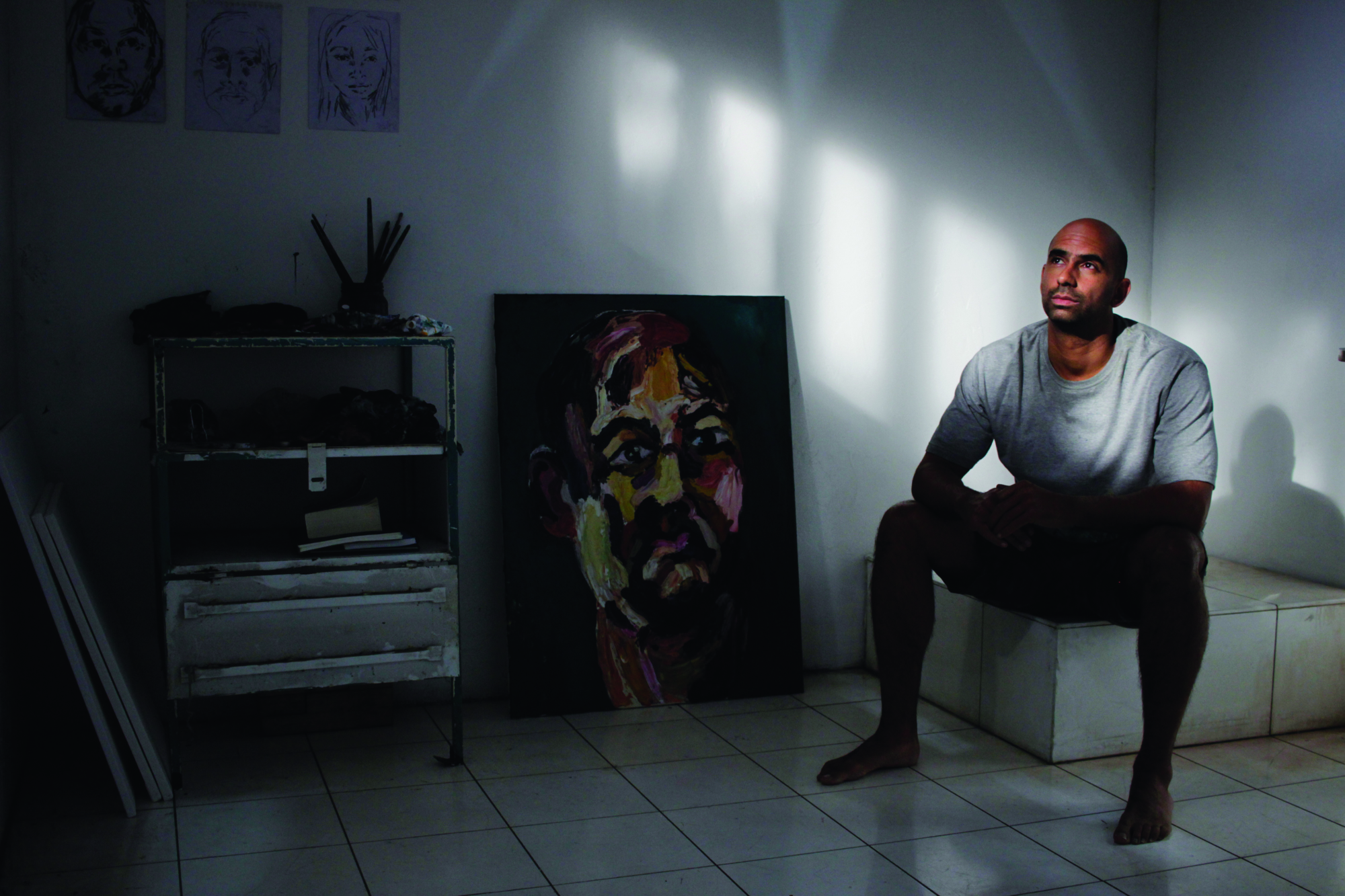

For much of the film, Guilty’s re-enacted scenes focus on Sukumaran – largely as he paints in his cell with feverish devotion, but also as he interacts with a friendly guard (played by Andre Ong Carlesso), contemplates his fate, faces court, says goodbye to his family and, finally, during the execution. As his final seventy-two hours count down, the documentary asks viewers to understand him through his actions and reactions, whether he’s waking in the night to the sound of gunshots as the firing squad rehearses, asking the guard to allow him to obtain signatures on one specific artwork from his fellow death-row inmates or embracing his loved ones for the last time. One lone re-enacted shot of Sukumaran on a mortuary slab, offered halfway through the piece, provides a particularly grim reminder of what awaits, though it’s in keeping with the film’s primary approach. In all of the above instances, Guilty requires the audience to peer straight at Sukumaran’s screen surrogate. Largely positioning him in the centre of the frame, where he is often looking at or near the camera, the film forces viewers to face a man condemned, to stare into his gaze and see him coping with the knowledge that he’ll soon die. It humanises him, showing a man rather than a face beneath a headline.

At the same time, in detailing the procedure around Sukumaran’s fate, Guilty trades in juxtapositions as part of its visual language. It cuts from Sukumaran placing a canvas on his easel in his cell to crosses being built to hold the condemned prisoners during the execution, and from him painting frenetically but contentedly to a man writing Sukumaran’s name, birthdate and death date on a cross. Again and again, Sleeth ensures that the audience doesn’t just see a kindly man pursuing his passion in prison, but remains aware of the unmistakable fact that his execution is imminent. Close-ups of other aspects of the preparation routine – such as bullets being lined up – further assist in reiterating the point. However, the film’s greatest reminder, and its greatest act of juxtaposition, is its exacting comparison of Sukumaran’s calm demeanour when facing any figure of authority with his equally composed expression as he stands tied to the cross, singing ‘Amazing Grace’ with his fellow condemned as red laser beams point at his chest, shots ring out and his white shirt is suddenly spattered with blood.

In the film’s final chapter, Sleeth offers yet another juxtaposition, this time between Sukumaran and his mother. First sighted in news footage, and then seen intermittently throughout the film travelling through Sydney by train, Raji is shown attending the opening night of her son’s posthumous exhibition Another Day in Paradise at the Campbelltown Arts Centre in January 2017. She views his art – the same pieces viewers have witnessed being painted during the film’s re-enactments, but now placed in a vastly different context. She walks through crowds of people in the open gallery space, a contrast to each painting’s creation by Sukumaran alone in his tiny Indonesian cell. Finally, she walks into a darkened screening room showing footage of her son, where he once again stares at the camera, as he has done in both actual and acted forms throughout the film. The camera zooms in, and he smiles: the documentary’s closest shot of the real-life Sukumaran’s face paired with his happiest expression – its divergence from everything that has preceded it, not to mention Sukumaran’s fate, painfully apparent.

While Sleeth’s approach to his subject matter sends a strong message, and demonstrates how to compellingly craft an emotional documentary through re-enactments, the dialogue he chooses to pair those with ultimately speaks louder than the film itself. Just as Sukumaran’s paintings prove more powerful than any images that the feature can provide, his words do the same, making his case in an even more effective manner. Of course, Guilty benefits strongly from both – and, in everything it compiles around Sukumaran’s art and statements, commandingly supports the executed man’s own expressions, as exemplified in three specific segments.

To-camera in news footage, the actual Sukumaran expounds on his art:

The main thing is that it sort of gives me a purpose in life. I think it is a way to express myself. To find out who I am, how I fit in the world – not just by my paintings, but by doing workshops. That’s also sort of art, yeah?

While standing before the court, when called on to sign his death warrant – as depicted in a re-enactment – he outlines:

Everything in this warrant is true, but I cannot sign this document. It’s true that I was caught smuggling drugs out of your country. It’s true that I was a criminal. It’s true that all my appeals failed. And now, finally, it seems true that you want to tie me to a post and kill me. In Kerobokan, I became an artist. I got a diploma in fine art from Curtin University, and I set up and ran art classes in the prison for six years. I’m not the person I was. I have changed. The only thing I have left is my truth, so if you include these facts, then I will sign the death warrant.

Finally, in a letter to his mother, read aloud in voiceover, he explains:

I don’t want you to be sad or traumatised by what happens. Some people go their entire lives without having their passion, and me, I have it for painting. I got to be an artist … I’ve created many things and helped so many people. Art has given me a purpose. If all of this hadn’t happened, I might never have been pushed to find that. If my paintings can help people to see that the death penalty is wrong, I’m happy.

https://clickv.ie/w/metro/guilty

Endnotes

| 1 | Jano Gibson, ‘Nine Australians Caught in Bali Drug Sting’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 18 April 2005, <https://www.smh.com.au/news/National/Nine-Australians-caught-in-Bali-drug-sting/2005/04/18/1113676689459.html>, accessed 25 May 2018. |

|---|---|

| 2 | ‘Australian Men Sentenced to Death’, BBC News, 14 February 2006, <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/4711208.stm>, accessed 25 May 2018. |

| 3 | Michael Safi & Dina Indrasafi, ‘Bali Nine Pair Among Eight Executed for Drug Offences in Indonesia’, The Guardian, 29 April 2015, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/28/bali-nine-pair-executed-indonesia>, accessed 25 May 2018. |