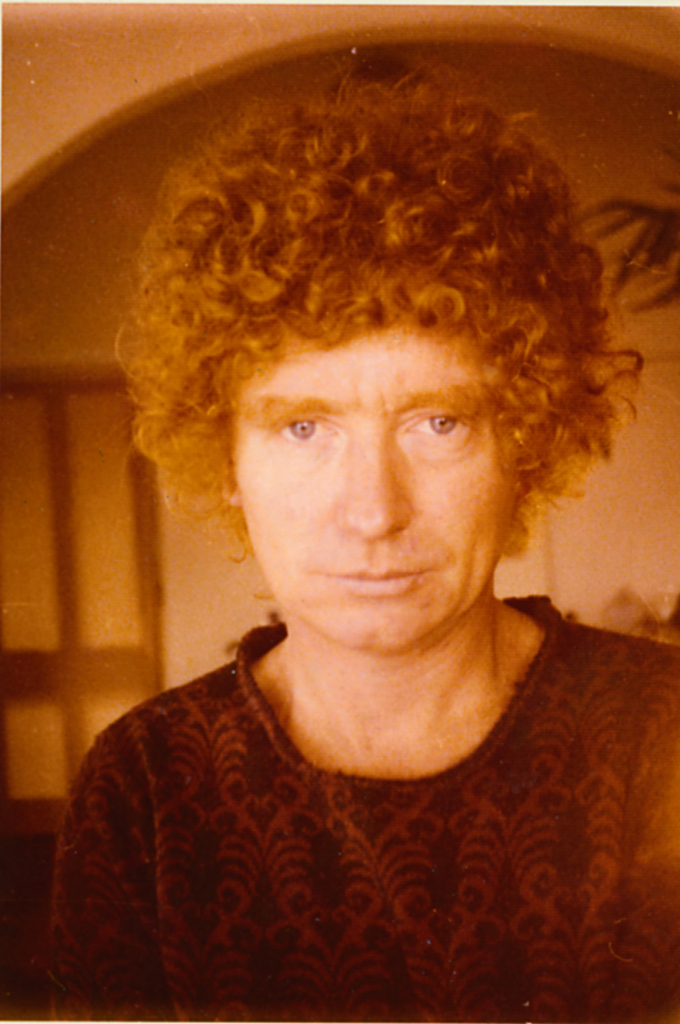

As is the case with many famous artists, the myth surrounding Brett Whiteley has a complex relationship with his actual life. For years, the public imagination has played on his charisma, his drug use, his marriage to Wendy Whiteley (née Julius) and his sudden, tragic death at just fifty-three in a hotel room in Thirroul, a coastal town 70 kilometres south of Sydney. However, while fans have admired and critics have debated, wider society has heard only snippets of the artist speaking in his own words.

Whiteley (2017) – co-written and directed by James Bogle, and produced and executive-produced by Sue Clothier – aims to expand the picture. Through never-before-heard interviews, archival footage, photographs and letters as well as images of more than a hundred of Brett’s artworks, the documentary transports viewers into the artist’s intimate world – emotional and physical – while, at the same time, guiding them chronologically through his life story. Complementing his words are interviews with Wendy, whom Brett married in 1962 and divorced in 1989.

‘I’ve always been drawn to big characters. I’d long been fascinated by Brett Whiteley, though I didn’t know much about him,’ Clothier tells me. ‘He’s iconic, he’s a great Australian, he’s a character […] so I started talking to James Bogle.’ For five-and-a-half years, Clothier and Bogle searched archives in Australia and overseas, looking for unique and unreleased material. Their sources included Wendy’s private files, particularly Brett’s notebooks, as well as family photographs and catalogues.

It took us a while to draw all the pieces together. As we dug into his story more and more, we fell in love with his art. So it became a voyage of discovery, to be honest, into the whole world of Brett Whiteley. Of course, as we dug into that, we started to understand how much his story is also Wendy’s.

The film’s opening scenes immerse the viewer in Brett’s mind, both visually and aurally. As numerous self-portraits appear in quick succession, each filling the screen, a voiceover by the artist himself – uninterrupted and urgent in tone – relates his metaphysical take on creativity:

In a sense, it is impossible to talk about art because I’ve always taken it for granted, and any attempt to pinpoint the necessity of one’s beginning only just arrives in a psychological shambles and inner dreams, etc. I’ve always understood, basically, that I used to be something else; that I’m a continuation of a particular kind of thread of human spirit; that the only thing that I’m involved in is the notion of interpreting time in a sense that I’m alive, that the spirit will continue, and it’ll be the same as what it was. And various painters are given their flash at it – and that, in summary, is basically what I’m doing.

The camera then cuts to footage of a Sotheby’s auction held in 2007, during which Opera House sells for A$2.8 million – establishing a record for the highest price paid for a Brett Whiteley painting.[1]‘Whiteley Painting Sells for Record Price’, ABC News, 8 May 2007, <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2007-05-07/whiteley-painting-sells-for-record-price/2542146>, accessed 14 August 2017. Following this, viewers hear various unidentified critics’ perspectives, from ‘He was a turkey, obsessed with sex, women’s bottoms, and worth flying overseas to avoid’ to ‘To watch him draw was as astonishing an experience as watching the young [Rudolf] Nureyev dance or the young [Marlon] Brando act’. In many ways, the documentary clarifies not only the myriad contradictory impressions of the artist, but also the contrast between them and his attempts at self-understanding. Clothier explains that she and Bogle

were drawn to trying to find this other side – not just the public face, but also the private Brett […] He was very much a public figure, very much a showman, but behind that he was very sensitive and very caring and very vulnerable – as an artist and as a man […] Criticism he took quite personally […] and that’s something I don’t think we’ve necessarily seen in the many news clips that we might recall.

Crucial to achieving this goal is the filmmakers’ depiction of Brett’s childhood. Again, rather than adopting an expository approach, they position the viewer ‘inside’ his experiences. In one sequence, the artist reminisces about Longueville, the suburb on Sydney’s North Shore where he grew up, remembering it as ‘tranquil, overlooking yachts […] When I go back [there], it looks the most satisfactory place that a kid could be brought up.’ In another, he recalls that, as a child, he ‘would hold up [his] paintings to [his] parents to get some approval’: ‘I thought that every time I did a drawing, if I was lucky, I would receive a piece of love.’ Following this, we see a collection of childhood paintings, and black-and-white photographs show Brett hugging his dog and smiling alongside his sister, Frannie.

‘As we dug into his story more and more, we fell in love with his art. So it became a voyage of discovery, to be honest, into the whole world of Brett Whiteley. Of course, as we dug into that, we started to understand how much his story is also Wendy’s.’

SUE CLOTHIER

When archival material is unavailable, animations and re-enactments dramatise Brett’s imaginative childhood universe. In one scene, his mother, Beryl, hits his father, Clement, over the head with a frypan – an action depicted with a suddenness that shocks the viewer, just as it would have shocked the young Brett. In a later scene, as the voiceover recounts Brett seeing Vincent van Gogh’s paintings for the first time in a book found accidentally on the school chapel’s floor, black-and-white photographs flood with colour in the distinctive style of van Gogh’s own brushstrokes. This poetic technique illustrates Brett’s admiration for van Gogh, with whom he felt

some connectedness of soul. I understood it. It was right. The immediate effect was a heightened reality, in that everything I looked at took on an intensity. That morning, I remember, the poplar trees were bare for winter. They now seethed with new lines. They were thickets of energy. I remember having this very powerful sense that my destiny was to completely give myself to painting.

Clothier explains that the filmmaking team ‘wanted the graphic effects to elevate the film tonally’ so as to

sit with where Brett was at in his life. They help make it entertaining, but they’re also a way of knitting together the archive so [that] it’s not just straight stills or straight notebooks. We wanted it to feel cinematic.

Such effects play a role, too, in conveying the Whiteleys’ romantic relationship. When the two are shown visiting the Louvre for the first time – Wendy, in voiceover, describes this as ‘one of the most extraordinary experiences of [their] lives’ – a black-and-white still of them looking at Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata by Giotto di Bondone is infused with heightened reality when the painting fills, unexpectedly, with colour. The camera captures it from the pair’s point of view, from a low angle, before panning slowly from bottom to top, allowing viewers to take in every detail and mimicking the subjects’ experience. ‘It was a shock,’ Wendy continues. ‘It was a cultural shock of such profound meaning that I just remember bursting into tears. Brett and I held hands and were overwhelmed, gazing at this extraordinary painting.’

‘[We] were drawn to trying to find this other side – not just the public face, but also the private Brett … He was very much a public figure, very much a showman, but behind that he was very sensitive and very caring and very vulnerable – as an artist and as a man.’

– Sue Clothier

Similarly, the couple’s daily life together in Florence, portrayed through re-enactments, is conveyed through the camera’s intense focus on particular details. Light-infused close-ups capture Brett’s (Andrew Blaikie) paintbrush applying thick, free strokes to the canvas, and Wendy (Jessica White) moving through the apartment. This home, in contrast with that of Brett’s troubled family, seems a happy, productive one, ruled by art and sensuality. In addition, Whiteley emphasises the artist’s determination and work ethic. Clothier recounts:

We were keen to show the audience that being an artist is a real job. Brett was very applied, and he really tried to say something through his art, whether it be a reflection on beauty or birds or beautiful structures […] He got up and painted every day.

Certainly, the film follows every aspect of Brett’s development – personal and artistic. Viewers trail the Whiteleys to London, where, at twenty-two, Brett became the youngest artist to be exhibited at the Tate, and where Wendy gave birth to the couple’s only daughter, Arkie; to New York, where they lived in the Chelsea Hotel and Brett painted The American Dream; to Fiji, where the family spent time resting and recuperating; and back to Sydney, where they moved to Lavender Bay. Throughout, Wendy’s voice is a strong presence – the audience becomes exposed not only to Brett’s perspective, but to hers, too. When the film travels to New York, for instance, we hear both parties’ impressions of the Chelsea Hotel while stills of Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Mick Jagger flash past. ‘It felt very safe because it was full of eccentrics,’ Wendy muses.

I loved it. The first studio in New York was one big room – called ‘The Penthouse’ – but, really, it was one room up some stairs, little kitchen and out onto this amazing roof garden. You know, the ducks were great watchdogs.

Beyond offering alternative viewpoints within the film, Clothier says, Wendy assisted directly with the curation of artworks.

The film couldn’t have been made without her. She’s the one who kept hold of the personal items and a lot of the art. She helped us to select the pieces that worked most brilliantly for each part of his life. That’s something we could never have done on our own […] She’s a critical part of the telling of the story. She talks about it as being her job, but also crucial is her determination to keep everything in one place. That’s the reason the studio is there. The garden is an offspring of all that as well […] She’s done an amazing job of pulling together and keeping alive the legacy […] It’s not easy. It takes a lot of strength.

Another figure for whom the film provides space, albeit to a much lesser degree, is landscape painter Lloyd Rees. In fact, one of its most poignant moments is a discussion about light between him and Brett, captured on film. Never publicly aired before, the footage was discovered by Clothier and Bogle at the Nine Network’s archives, where it was stored as a B-roll in a canister labelled only with the word ‘Whiteley’. Clothier describes it as ‘one of her favourite pieces in the film […] a lovely conversation that the audience drops into […] a beautiful insight into two artists and how they use light’.

But there is also darkness – Whiteley does not shy away from addressing the couple’s heroin addiction, which contributed to their divorce in 1989 and led to Brett’s death by overdose in 1992. However, neither does the film lend disproportionate weight or take a sensationalised approach to the topic of illegal substances. ‘Drugs are not what defined Brett Whiteley. They’re a thing that happened – just one part of the picture,’ Clothier says.

He had already made it in his very early twenties, well before any drug use kicked in […] It would’ve been easy [for the filmmaking team] to do something that was ‘sex, drugs and rock’n’roll’, but that wouldn’t have been the right thing to do. Stories can often get skewed when drugs are involved, and I think that’s a pity because that can overshadow [a] brilliant and extraordinary story […] This film is very much about trying to keep the right balance of everything.

Indeed, Whiteley is a moving, skilfully shot tribute to one of Australia’s finest artists. Through a combination of never-before-seen materials, pieced together with a powerful storytelling style, the documentary aims to both preserve its subject’s legacy and draw new attention to his art. ‘Brett passed away more than twenty years ago now,’ Clothier says.

We want to stir people who are unfamiliar with his works – be [they] in Australia or around the world – [so that] if they see his work, they might be interested enough to enquire more about who this person is. He was an amazing Australian, with an authentic voice, whose work speaks.

http://www.transmissionfilms.com.au/films/whiteley/

Endnotes

| 1 | ‘Whiteley Painting Sells for Record Price’, ABC News, 8 May 2007, <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2007-05-07/whiteley-painting-sells-for-record-price/2542146>, accessed 14 August 2017. |

|---|