In many ways, Midnight Oil: 1984 (2018) serves as a culmination of several years’ collaboration between director Ray Argall and the iconic Australian band. Having worked on several videos and concert films for them from 1982 to 1986, Argall embedded himself among Midnight Oil to document their national tour for the 1984 album Red Sails in the Sunset. While the tour itself marked a bold new direction for the band, who were undertaking promotional duties for themselves for the first time, an added wrinkle came with frontman Peter Garrett agreeing to take the role of Senate candidate for the newly formed Nuclear Disarmament Party (NDP). The band were always staunchly political in their art, particularly regarding the issue of nuclear proliferation, but this tumultuous collision of the politics and music worlds would resonate through the following eighteen years of the band’s career, and lead Garrett on a path to political office in the cabinets of prime ministers Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard. As the film’s press release puts it:

With the mounting pressure of balancing the demands of music and politics [1984] is the year that would make, but nearly break, Australia’s most important rock and roll band […] the film tells how a group of awesomely talented musicians with a powerful and ambitious message were able to inspire a generation to try and change the world.[1]Madman, Midnight Oil: 1984 press kit, 2018, pp. 2–3.

Constructed, in large part, from the wealth of 16mm footage shot by Argall of the band during the titular year, Midnight Oil: 1984 is a film in two halves. The first is what its synopsis says it is: a snapshot of one of Australia’s greatest bands at the peak of their relevance. A lengthy opening sequence showing backstage preparations before a Midnight Oil gig not only serves as metaphor for the looming politically charged storm, but also showcases Argall’s talent for capturing the mounting energy that suffuses the air in the lull prior to showtime. In these sequences, that curious mixture of nervous tension and quiet confidence common to experienced performers, displayed by roadies and band members alike, is cut through with the barely contained excitement of the arriving punters. Argall’s editing flows like a virtuoso jazz performance – exact and methodical while simultaneously thrumming with an energy that sees full release in the film’s stunning performance sequences. If there’s one thing Midnight Oil: 1984 does better than portray the backstage atmosphere of the shows, it’s showing just what the band were capable of in front of a crowd.

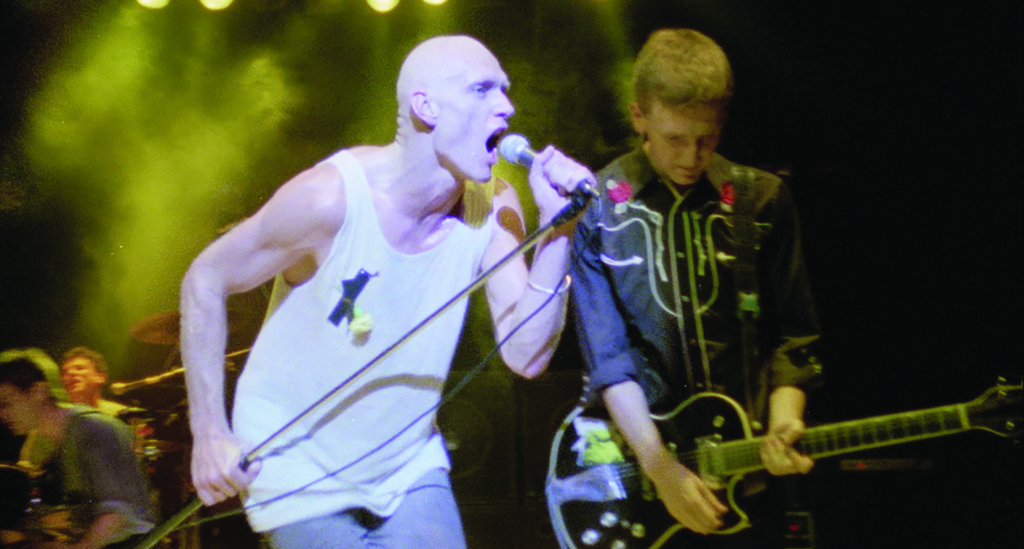

With audiences packed into smaller venues where tickets are half the usual price – a point of pride for a band acting as its own promoter – the shows are a maelstrom of unbridled passion, the ceilings at points practically dripping with sweat. While the footage is excellently shot, characterised by an almost guerrilla-style vigour that puts us in the shoes of fan and band alike, it’s the sound mix that impresses the most. Unlike most films featuring live performances (including dedicated concert films), Midnight Oil: 1984 recognises the importance of keeping the crowd audible, and the cacophonous, at times borderline-violent, din generated by the fans goes a long way towards selling the impressive intensity of the Oils’ performances at this time.

While the band are uniformly tight and ferociously energetic, it’s their gangly, bald singer who perpetually draws the eye. Garrett prowls the stage – limbs akimbo, vein and sinew looking as if in competition to burst from his skin – yet is shockingly articulate and good-natured between songs, proselytising on politics, nuclear disarmament and crowd etiquette like the fans’ cool older brother. As great as Midnight Oil were as a band, these sequences make it clear that it was always, fundamentally, the Garrett Show. Midnight Oil: 1984 follows this tradition. The film’s nebulous other half is intended to be a portrait of the era’s fears and frustrations over nuclear arms, environmental decline and Indigenous issues, and a celebration of Garrett’s role as a galvanising lodestone for young people’s concerns about these issues. Certainly, the film makes a great deal of the singer’s common touch. It’s a striking reminder of why this wholly unlikely-looking rock star – with his gangly frame; angular, cue-ball head; and dance moves like a 1950s robot fighting a swarm of wasps – also happens to be one of the very best Australia has ever produced.

Very few rock stars can make interrupting a show to talk about social justice even halfway palatable; Garrett made it utterly compelling, and did so with no apparent effort. The Midnight Oil frontman, Argall’s film posits, was a born politician just waiting for the right party.

More pointedly, however, we also see, in footage of his between-song stage patter, a preternatural eloquence, focus and ability to work a crowd. Very few rock stars can make interrupting a show to talk about social justice even halfway palatable; Garrett made it utterly compelling, and did so with no apparent effort. The Midnight Oil frontman, Argall’s film posits, was a born politician just waiting for the right party. We see Garrett give talks at schools and handle press junkets and debates with competing political candidates equally as deftly as he controls and preaches to concert audiences. Complementing these scenes is vox-pop footage of fans attending the shows, which illustrates just how effective Garrett was in broaching politics with the band’s audience. These sequences not only show him to be an instinctively talented speaker and political operator, but also serve as cases in point of how a magnetic personality can function as a figure head for the public consciousness.

It’s here, however, that the film becomes less about the band, and more about their leader. While Midnight Oil outwardly supported Garrett’s campaign, the other members do, in contemporary inteviews, bring up the strain it put not just on their operations as performers, but also on Garrett himself. While guitarist Jim Moginie recalls the singer being ‘on top of the world’ during his foray into politics, drummer Rob Hirst paints a picture of a man pushing himself to near-breaking point under the immense pressure of attending to meetings and press duties by day, throwing himself into their intense performances at night, and getting up the next day to do it all over again. Very little is said about how the band members themselves actually felt about all this personally; it doesn’t feel intentional, but they nevertheless come across as rock’n’roll versions of clichéd 1950s ‘dutiful wives’, waiting for hubby to come home from work – only clutching musical instruments rather than baking trays.

The band may have remained active, but they had become addenda to Garrett’s political work. It’s easy to sympathise with them, especially when opposing party candidates challenge the singer to leave the band should he be successful in winning a Senate seat. Political mind games aside, the members of Midnight Oil were fully aware that Garrett would be faced with exactly that dilemma if he won. Further to that, it would have been hard for him to refuse to take that step without it ultimately harming the band’s political credibility.

Again, Argall does little to elucidate the band’s opinions past the cursory, and past anything that isn’t related to Garrett and his struggles. It creates an odd tension that’s often seen at the heart of collaborative environments led by a charismatic personality. On the one hand, it’s clear that the other members are as much a part of Midnight Oil’s success as Garrett, both musically and in performance (it’s pointed out that, from the early days, the singer wisely encouraged the other members to perform for the audience as well, rather than put the onus solely on him). On the other, there also exists an urge of sorts to continually defer to that personality; Midnight Oil: 1984 may claim to be a film about the group, but, in practice, the focus is kept on the singer at all times, even when the other members are speaking. There’s something fascinating in the interplay between that kind of cult of personality and the group dynamic, but it’s left unexplored here.

While the film astutely suggests that this brief run for Senate sowed the seeds for Garrett’s post-band political career with the Australian Labor Party, a rushed conclusion weirdly undersells the fact that Midnight Oil was active for another eighteen years, before breaking up in 2002. The band’s sense of unity actually withstood this period – and the growing cult of personality around Garrett – far better than the documentary seems willing to give space to convey, which again doesn’t jibe with the stated intentions of the filmmakers. The documentary also observes that, while a magnetic-enough personality can cross worlds (in this case, from music to politics), such transitions come with their own problems. Garrett is beset by accusations, from pundits and opponents alike, of essentially being a career tourist: naive and unprepared for political life. These doubts about his ability resonate not just for the purposes of the film’s narrative, but also in light of how they would come back to haunt him during his stint in the Rudd and Gillard cabinets. Indeed, it’s the way that Midnight Oil: 1984 dodges the question of Garrett’s later career that is its biggest stumbling block. Anyone in Australia who hasn’t been living as a hermit for the last decade will know that Garrett’s stint in government was highly controversial, with him attracting numerous accusations of compromising his well-pronounced ideals for the sake of party politics.[2]See Sam Clench, ‘Peter Garrett Opens Up About “Dark Nights of the Soul” as a Minister’, News.com.au, 28 June 2013, <https://www.news.com.au/national/peter-garrett-opens-up-about-8216dark-nights-of-the-soul8217-as-a-minister/news-story/2a2f59eb2989c08bcbdd2be1036c06ec>, accessed 30 July 2018. His approval of the Beverley uranium mine in 2009 was particularly contentious, and a complete turnaround from the passionately anti-nuclear stance he held with the NDP.[3]See Michelle Grattan & Barry Fitzgerald, ‘Garrett Gives Nod to Uranium Mine’, The Age, 15 July 2009, <https://www.theage.com.au/national/garrett-gives-nod-to-uranium-mine-20090714-dk5w.html>, accessed 30 July 2018.

Of course, that’s not to say that Argall or his film are under any obligation to take Garrett to task for this: politics is messy by nature, especially at the highest levels, and Garrett has always come across as a fundamentally decent man. Indeed, for all his mistakes, he also succeeded in doing a great deal of good: aligning Australia in the fight against Japanese whaling,[4]See ‘Garrett Targets Japan’s Whaling Loophole’, ABC News, 28 April 2010, <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2010-04-28/garrett-targets-japans-whaling-loophole/413404>, accessed 30 July 2018. locking down the Gonski reforms to education[5]See ‘Huge Day for Education, Says Garrett’, SBS News, 20 February 2012, <https://www.sbs.com.au/news/huge-day-for-education-says-garrett>, accessed 30 July 2018. and having several successes in arts funding.[6]See, for example, ‘Garrett Announces $37.5m in Indigenous Arts Funding’, ABC News, 14 August 2008, <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2008-08-14/garrett-announces-375m-in-indigenous-arts-funding/476334>, accessed 30 July 2018. Nevertheless, it seems his failures will always remain topical, given the lengths the film goes to in constructing its narrative of Garrett as a rocking ‘perfect storm’ of ideals and political eloquence.

The film may have been conceived as a look into the state of the band in 1984 – long before Garrett’s political run proper – but the problem is that it hobbles itself in that goal by including contemporary interview footage with Garrett, the band and those in their orbit at the time. If Argall had stuck to constructing the film purely from the archival footage, making it a time capsule with narrative distance from Garrett’s future career, then that would have felt more artistically satisfying. However, the presence of these contemporary interviews creates implications that overshadow their narrative role in the context of the overall work. The result is an elephant-in-the-room situation whereby we have the players talking about events from thirty years previously, and knowing – but not talking about – where these events eventually led.

Not only does this come across as rather disingenuous given the ‘Garrett as white knight’ narrative, but it also avoids more probing questions about celebrity in politics. Do politically active celebrities awaken awareness or a sense of novelty in people? Can someone truly maintain a particular image in a position of political authority, especially if that image has been cultivated in a different career? And, with Midnight Oil’s recent return to touring, can you truly come home again after crossing the line between politically conscious artist and political careerist?

Ultimately, Midnight Oil: 1984 is not here to ask those questions. Its goal is to celebrate a band – and, in particular, its frontman – during a very specific period of time. While its thematic meat invites questions about celebrity and the power of personality, it’s a film for fans (specifically, older ones) wanting to relive that period. In that sense, perhaps it’s fair to recognise my own perspective on Garrett, and Midnight Oil in general. Having been born in Australia to English parents, and with us having moved to the UK in 1984, I only became exposed to the band upon my return to Australia in 1997, during the waning stages of their career. While Midnight Oil: 1984 works as a lesson in just how good a band they were, particularly in a live setting, I don’t have that ingrained affection for them to which Argall is playing.

Then again, the film itself celebrates the fact that the Oils didn’t just create fans, but politically aware fans. It’s hard to imagine such fans watching this film and wondering about the gap between Garrett as political idealist in 1984 and the older, infinitely more controversial man speaking for him on screen.

Midnight Oil: 1984 is an excellent rock documentary when it allows itself to be. However, it stumbles by underselling the band as a collective unit, while pulling punches when it comes to its real focus: Peter Garrett. The film gets no small amount of mileage out of suggesting how a strong personality can both mould a group dynamic and shift public perception, but – much like a regular accusation levied at Garrett himself during his stint in government – it is too eager to please to go too far in any definite direction.

Endnotes

| 1 | Madman, Midnight Oil: 1984 press kit, 2018, pp. 2–3. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Sam Clench, ‘Peter Garrett Opens Up About “Dark Nights of the Soul” as a Minister’, News.com.au, 28 June 2013, <https://www.news.com.au/national/peter-garrett-opens-up-about-8216dark-nights-of-the-soul8217-as-a-minister/news-story/2a2f59eb2989c08bcbdd2be1036c06ec>, accessed 30 July 2018. |

| 3 | See Michelle Grattan & Barry Fitzgerald, ‘Garrett Gives Nod to Uranium Mine’, The Age, 15 July 2009, <https://www.theage.com.au/national/garrett-gives-nod-to-uranium-mine-20090714-dk5w.html>, accessed 30 July 2018. |

| 4 | See ‘Garrett Targets Japan’s Whaling Loophole’, ABC News, 28 April 2010, <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2010-04-28/garrett-targets-japans-whaling-loophole/413404>, accessed 30 July 2018. |

| 5 | See ‘Huge Day for Education, Says Garrett’, SBS News, 20 February 2012, <https://www.sbs.com.au/news/huge-day-for-education-says-garrett>, accessed 30 July 2018. |

| 6 | See, for example, ‘Garrett Announces $37.5m in Indigenous Arts Funding’, ABC News, 14 August 2008, <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2008-08-14/garrett-announces-375m-in-indigenous-arts-funding/476334>, accessed 30 July 2018. |